The Impact of COVID-19 from the Perspectives of Dutch District Nurses: A Mixed-Methods Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Setting and Participant Selection

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. Individual Interviews

2.3.2. Follow-Up Questionnaire

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Interviews

2.4.2. Follow-Up Questionnaire

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

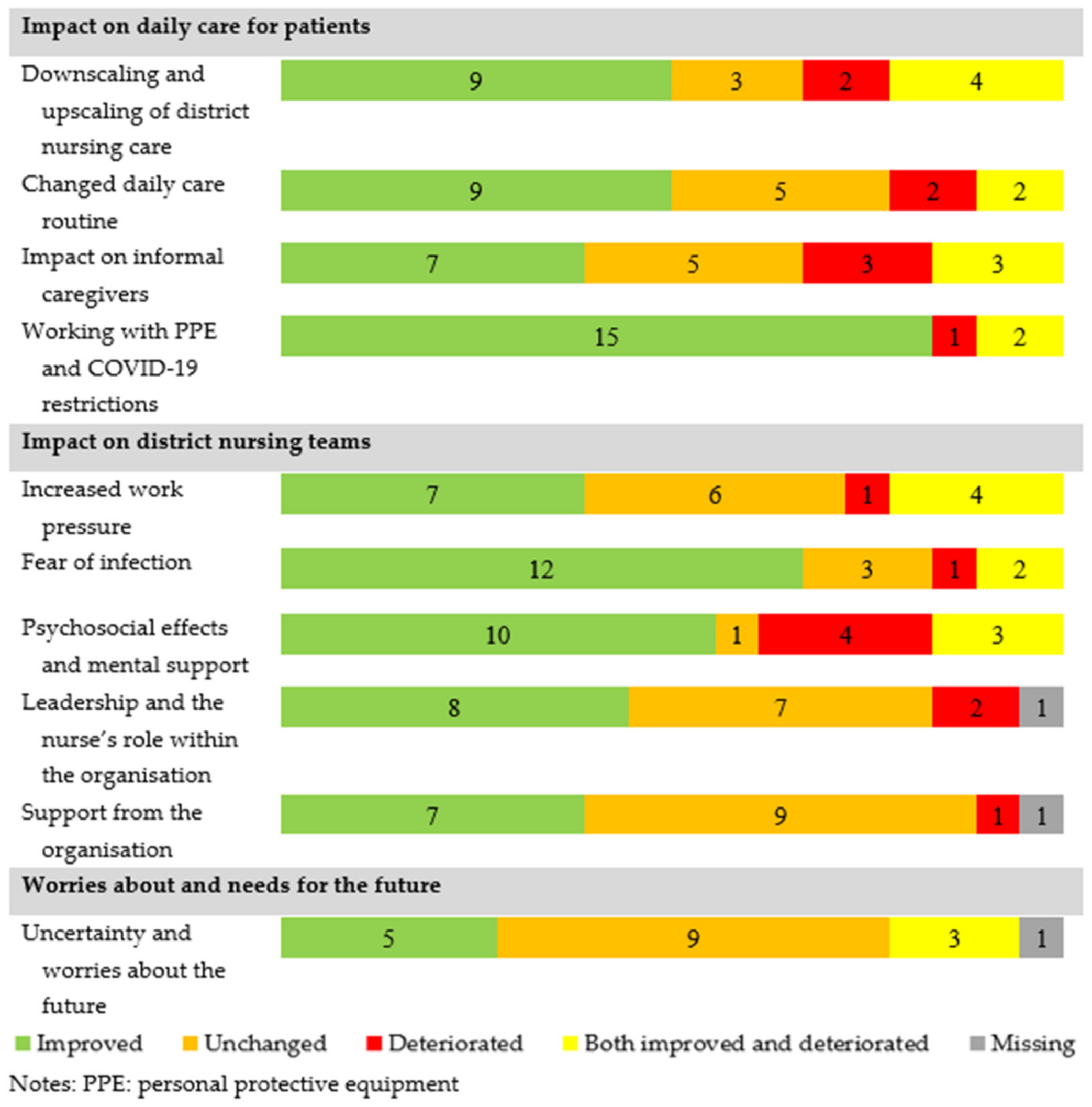

3.1. Impact on Daily Care for Patients

3.1.1. Downscaling and Upscaling of District Nursing Care

3.1.2. Changed Daily Care Routine

3.1.3. The Impact on Informal Caregivers

3.1.4. Working with PPE and COVID-19 Restrictions

3.2. Impact on District Nursing Teams

3.2.1. Increased Work Pressure

3.2.2. Fear of Infection

3.2.3. Psychosocial Effects and Mental Support

3.2.4. Leadership and the Nurse’s Role within the Organisation

3.2.5. Support from the Organisation

3.3. Worries about and Needs for the Future

3.3.1. Uncertainty and Worries about the Future

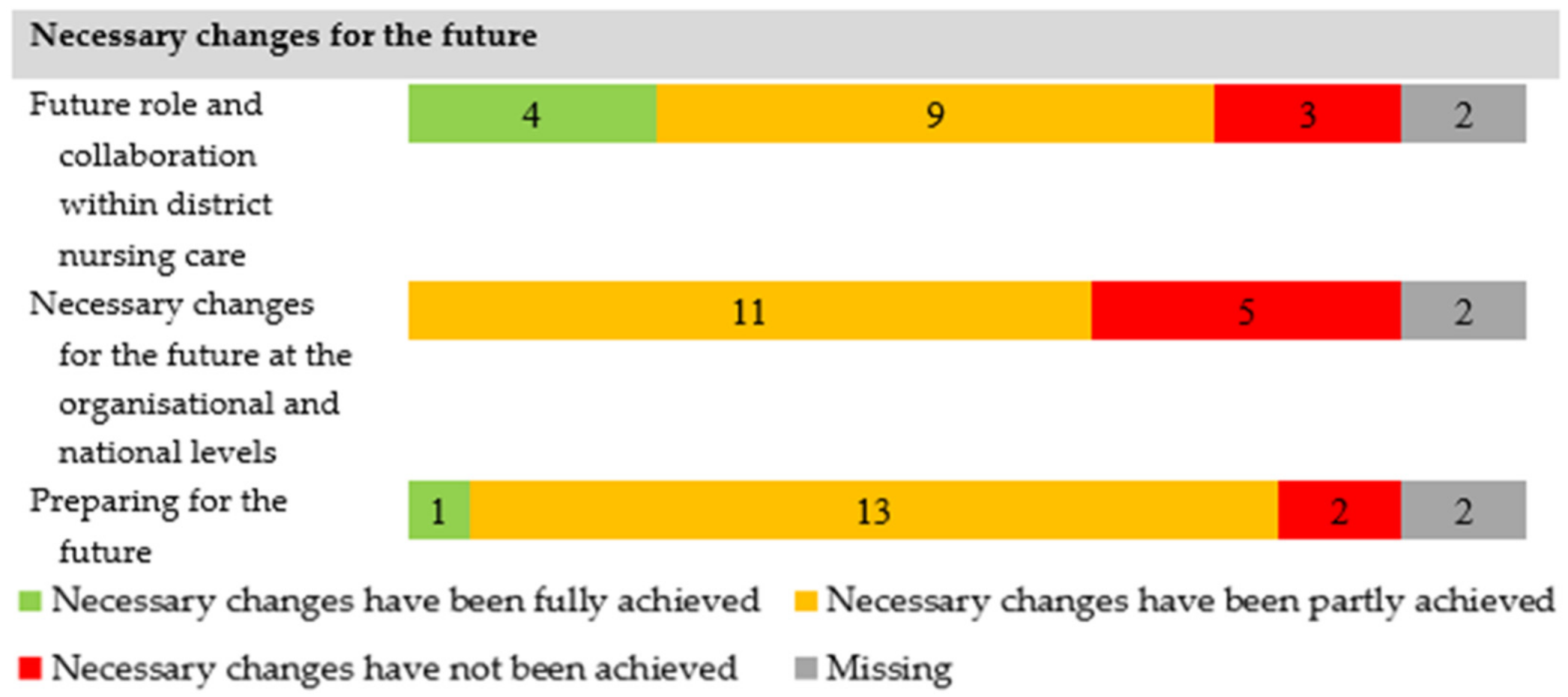

3.3.2. Future Role and Collaboration within District Nursing Care

3.3.3. Necessary Changes for the Future at the Organisational and National Levels

3.3.4. Preparing for the Future

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Implications for Practice, Policy and Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Guide

| General Questions |

| ● Are you currently working in district nursing care? If not, where are you working? If not related to district nursing care, finish the interview |

| ● At what organisation are you working? |

| ● For how long have you been working in district nursing care? |

| ● What is your function title? |

| ● How old are you? |

| Specific Questions Regarding the Impact of COVID-19 on District Nursing Care |

| ● What impact have you experienced as a result of the COVID-19 crisis? |

| ● What is the impact of COVID-19 on the client? |

| ● What is the impact of COVID-19 on the organisation and organisational decisions? |

| ● Are you well equipped in your work in district nursing care to properly perform your role during the COVID-19 crisis? Please explain. |

| ● Where are the greatest needs in district nursing care at this moment (during the COVID-19 crisis)? |

| ● What challenges do you foresee for yourself, the client, and the organisation in the near future? |

| ● What do you need and from whom to respond to these challenges? |

Appendix B. Online Questionnaire

| Question | Answer Options |

| What is your gender? | Male Female I’d rather not say |

| How old are you? | <open field> |

| What is your current function? | District nurse (bachelor’s degree required) Specialised nurse Nurse specialist Other <open field> |

| What is your education level? | Bachelor’s degree Master’s degree at a university for applied science Master’s degree in education at university |

| How many hours per week do you work in district nursing care? | <open field> |

| How long have you been working in district nursing care? | <open field> |

| Question | Answer Options |

| Do you recognise the above description of [the subtheme] in district nursing care during the first outbreak? If not, please explain | Yes No <open field> |

| How is the current situation of downscaling in district nursing care? | Situation is improved Situation is unchanged Situation is deteriorated Situation is both improved and deteriorated |

| Please explain | <open field> |

| Question | Answer Options |

| Do you recognise the above description of [the subtheme] in district nursing care during the first outbreak? If not, please explain | Yes No, <open field> |

| Has the situation regarding your future role and collaboration in district nursing care already been realised or implemented? | Yes Yes, partly No |

| Please explain | <open field> |

| Question | Answer Options |

| What has helped you the most during the COVID-19 crisis in district nursing care? | <open field> |

| What has bothered you the most during the COVID-19 crisis in district nursing care? | <open field> |

| This is the final question. If there is anything else you would like to say about this subject or research, you can do so here. | <open field> |

References

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) The Impact of COVID-19 on Health and Health Systems. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/health/covid-19.htm (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- World Health Organization Timeline: WHO Response COVID-19. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/interactive-timeline/ (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Green, J.; Doyle, C.; Hayes, S.; Newnham, W.; Hill, S.; Zeller, I.; Graffin, M.; Goddard, G. COVID-19 and District and Community Nursing. Br. J. Community Nurs. 2020, 25, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowers, B.; Pollock, K.; Oldman, C.; Barclay, S. End-of-Life Care during COVID-19: Opportunities and Challenges for Community Nursing. Br. J. Community Nurs. 2021, 26, 44–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stall, N.; Nowaczynski, M.; Sinha, S.K. Systematic Review of Outcomes from Home-Based Primary Care Programs for Homebound Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2014, 62, 2243–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasper, A. Care in Local Communities: A New Vision for District Nursing. Br. J. Nurs. 2013, 22, 236–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genet, N.; Boerma, W.; Kroneman, M.; Hutchinson, A.; Saltman, R.B.; World Health Organization. Home Care across Europe: Current Structure and Future Challenges; World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Van Eenoo, L.; Declercq, A.; Onder, G.; Finne-Soveri, H.; Garms-Homolova, V.; Jonsson, P.V.; Dix, O.H.; Smit, J.H.; van Hout, H.P.; van der Roest, H.G. Substantial Between-Country Differences in Organising Community Care for Older People in Europe—A Review. Eur. J. Public Health 2016, 26, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jarrín, O.F.; Pouladi, F.A.; Madigan, E.A. International Priorities for Home Care Education, Research, Practice, and Management: Qualitative Content Analysis. Nurse Educ. Today 2019, 73, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurits, E.E.M. Autonomy of Nursing Staff and the Attractiveness of Working in Home Care. Ph.D. Thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sterling, M.R.; Tseng, E.; Poon, A.; Cho, J.; Avgar, A.C.; Kern, L.M.; Ankuda, C.K.; Dell, N. Experiences of Home Health Care Workers in New York City during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic: A Qualitative Analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 180, 1453–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J. The Needs of District and Community Nursing. Natl. Health Exec. 2021, 3, 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Osakwe, Z.T.; Osborne, J.C.; Samuel, T.; Bianco, G.; Céspedes, A.; Odlum, M.; Stefancic, A. All Alone: A Qualitative Study of Home Health Aides’ Experiences during the COVID-19 Pandemic in New York. Am. J. Infect. Control 2021, 49, 1362–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, I.; Zhang, J.; Bevilacqua, G.; Lawrence, W.; Ward, K.; Cooper, C.; Dennison, E. The Experiences of Community-Dwelling Older Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Preliminary Findings from a Qualitative Study with Hertfordshire Cohort Study Participants; BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.: London, UK, 2021; p. 52. [Google Scholar]

- Heid, A.R.; Cartwright, F.; Wilson-Genderson, M.; Pruchno, R. Challenges Experienced by Older People during the Initial Months of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Gerontologist 2021, 61, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, M.A.; McDermott, S. The COVID-19 Pandemic and People with Disability. Disabil. Health J. 2020, 13, 100944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Factsheet Wijkverpleging. Available online: https://www.vektis.nl/intelligence/publicaties/factsheet-wijkverpleging (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Grijpstra, D.; De Klaver, P.; Meuwissen, J. De Situatie Op de Arbeidsmarkt in de Wijkverpleging; Panteia: Zoetermeer, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kroneman, M.; Boerma, W.; Van den Berg, M.; Groenewegen, P.; De Jong, J.; Van Ginneken, E. The Netherlands: Health System Review; NIVEL: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Postma, J.; Oldenhof, L.; Putters, K. Organized Professionalism in Healthcare: Articulation Work by Neighbourhood Nurses. J. Prof. Organ. 2015, 2, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolbers, I.; Lalleman, P.C.; Schoonhoven, L.; Bleijenberg, N. The Ambassador Project: Evaluating a Five-Year Nationwide Leadership Program to Bridge the Gap between Policy and District Nursing Practice. Policy Polit. Nurs. Pract. 2021, 22, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) The Development of COVID-19 in Graps (in Dutch: Ontwikkeling COVID-19 in Grafieken). Available online: https://www.rivm.nl/en/node/154271 (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Qualtrics; Qualtrics: Provo, UT, USA, 2021 [software]. Available online: www.qualtrics.com (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Statistics Netherlands (in Dutch: Centraal Bureau van Statistiek, CBS). Labor Market Profile of Care and Welfare [in Dutch: Arbeidsmarktprofiel van zorg en Welzijn]. Available online: https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/longread/statistische-trends/2020/arbeidsmarktprofiel-van-zorg-en-welzijn/6-arbeidsomstandigheden (accessed on 12 September 2021).

- Shang, J.; Chastain, A.M.; Perera, U.G.E.; Quigley, D.D.; Fu, C.J.; Dick, A.W.; Pogorzelska-Maziarz, M.; Stone, P.W. COVID-19 Preparedness in US Home Health Care Agencies. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 924–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, A.; Maclagan, L.C.; Schumacher, C.; Wang, X.; Jaakkimainen, R.L.; Guan, J.; Swartz, R.H.; Bronskill, S.E. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Home Care Services among Community-Dwelling Adults with Dementia. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 2258–2262.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, E.Y.Y.; Gobat, N.; Kim, J.H.; Newnham, E.A.; Huang, Z.; Hung, H.; Dubois, C.; Hung, K.K.C.; Wong, E.L.Y.; Wong, S.Y.S. Informal Home Care Providers: The Forgotten Health-Care Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Lancet 2020, 395, 1957–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C. The Structural Vulnerability of Healthcare Workers during COVID-19: Observations on the Social Context of Risk and the Equitable Distribution of Resources. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 258, 113119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, N.; Docherty, M.; Gnanapragasam, S.; Wessely, S. Managing Mental Health Challenges Faced by Healthcare Workers during Covid-19 Pandemic. BMJ 2020, 368, m1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Denton, M.; Zeytinoglu, I.U.; Davies, S.; Lian, J. Job Stress and Job Dissatisfaction of Home Care Workers in the Context of Health Care Restructuring. Int. J. Health Serv. 2002, 32, 327–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shotwell, J.L.; Wool, E.; Kozikowski, A.; Pekmezaris, R.; Slaboda, J.; Norman, G.; Rhodes, K.; Smith, K. “We Just Get Paid for 12 Hours a Day, but We Work 24”: Home Health Aide Restrictions and Work Related Stress. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frawley, T.; Van Gelderen, F.; Somanadhan, S.; Coveney, K.; Phelan, A.; Lynam-Loane, P.; De Brún, A. The Impact of COVID-19 on Health Systems, Mental Health and the Potential for Nursing. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2021, 38, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu-Ching, C.; Yeur-Hur, L.; Shiow-Luan, T. Nursing Perspectives on the Impacts of COVID-19. J. Nurs. Res. 2020, 28, e85. [Google Scholar]

- Stuurgroep Kwaliteitskader Wijkverpleging. Kwaliteitskader Wijkverpleging; Zorginstituut Nederland: Diemen, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- American Nurses Association. Home Health Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice; American Nurses Association: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Community Health Nurses of Canada (CHNC). Canadian Community Health Nursing Professional Practice Model & Standards of Practice; Community Health Nurses of Canada (CHNC): Midland, TX, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mildon, B. The Concept of Home Care Nursing Workload: Analysis and Significance. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. Delivering High Quality, Effective, Compassionate Care: Developing the Right People with the Right Skills and the Right Values: A Mandate from the Government to Health Education England: April 2013 to March 2015; Department of Health: London, UK, 2016.

- Chief Nursing Officer Directorate. Transforming Nursing, Midwifery and Health Professions’(NMaHP) Roles: Pushing the Boundaries to Meet Health and Social Care Needs in Scotland. Paper 3: The District Nursing Role in Integrated Community Nursing Teams; Scottish Government: Edinburgh, UK, 2017.

- Barrett, D.; Heale, R. COVID-19: Reflections on Its Impact on Nursing. BMJ Evid.-Based Nurs. 2021, 24, 112–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Interviews (2020) N = 36 | Follow-Up Questionnaire (2021) N = 18 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age; mean (sd) | 43.0 (12) | 42.5 (10.3) |

| Sex: female; n (%) | 33 (91.7) | 18 (100) |

| Function; n (%) | 19 4 1 2 | 14 3 1 0 |

| ||

| Years of experience in district nursing care; mean (SD) | 9.5 (5.2) | 14 (7.0) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Veldhuizen, J.D.; Zwakhalen, S.; Buurman, B.M.; Bleijenberg, N. The Impact of COVID-19 from the Perspectives of Dutch District Nurses: A Mixed-Methods Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413266

Veldhuizen JD, Zwakhalen S, Buurman BM, Bleijenberg N. The Impact of COVID-19 from the Perspectives of Dutch District Nurses: A Mixed-Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(24):13266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413266

Chicago/Turabian StyleVeldhuizen, Jessica D., Sandra Zwakhalen, Bianca M. Buurman, and Nienke Bleijenberg. 2021. "The Impact of COVID-19 from the Perspectives of Dutch District Nurses: A Mixed-Methods Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 24: 13266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413266

APA StyleVeldhuizen, J. D., Zwakhalen, S., Buurman, B. M., & Bleijenberg, N. (2021). The Impact of COVID-19 from the Perspectives of Dutch District Nurses: A Mixed-Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(24), 13266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413266