In the Eye of the Storm: A Quantitative and Qualitative Account of the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Dutch Home Healthcare

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. First Phase: Quantitative Methodology

2.2.1. Sampling and Data Collection

2.2.2. Data Analysis

2.3. Second Phase: Qualitative Methodology

2.3.1. Participants

2.3.2. Data Collection

2.3.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Data Management

2.5. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Impact of the Pandemic on HHC Utilization

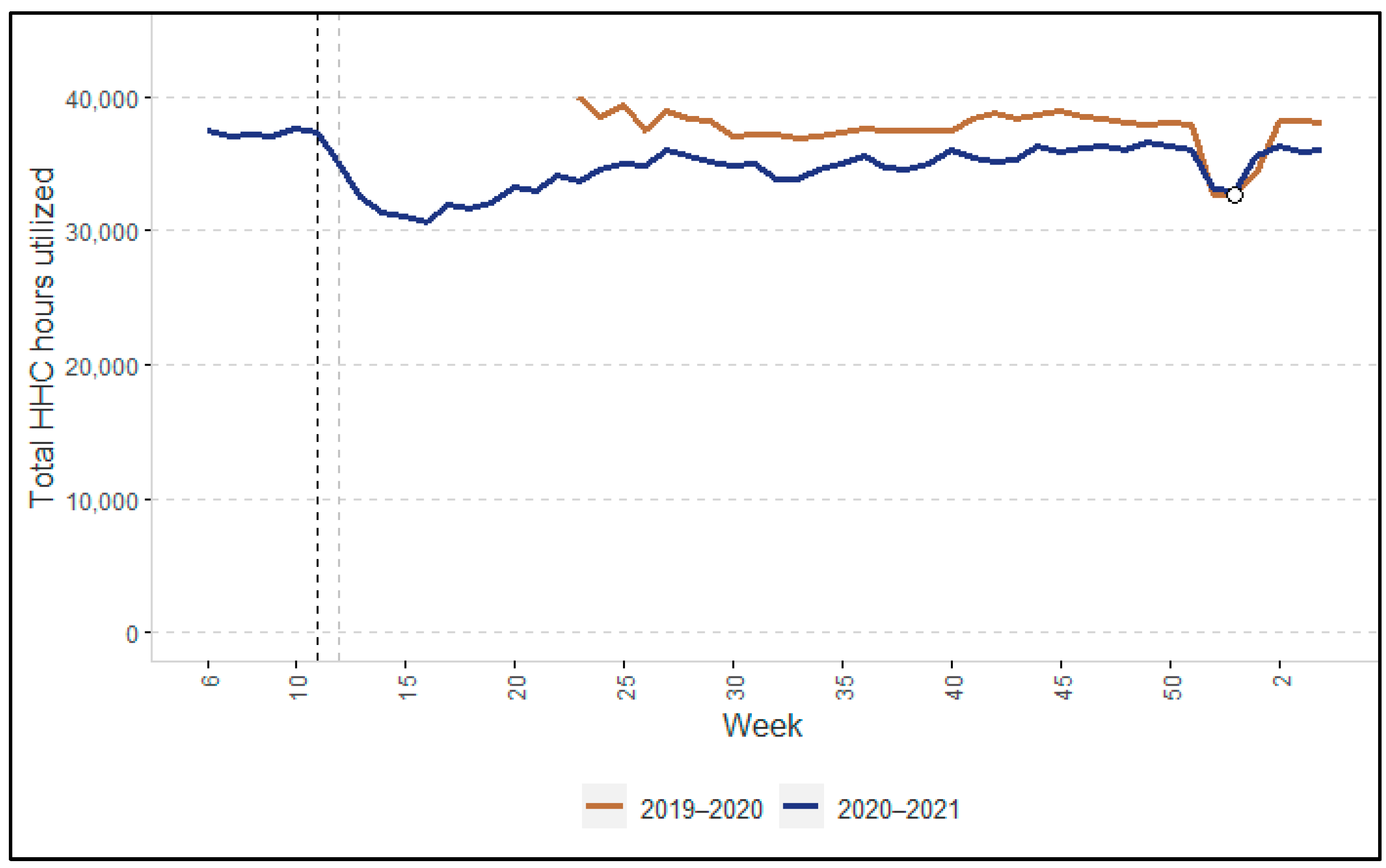

3.1.1. Changes in Hours of HHC Utilized

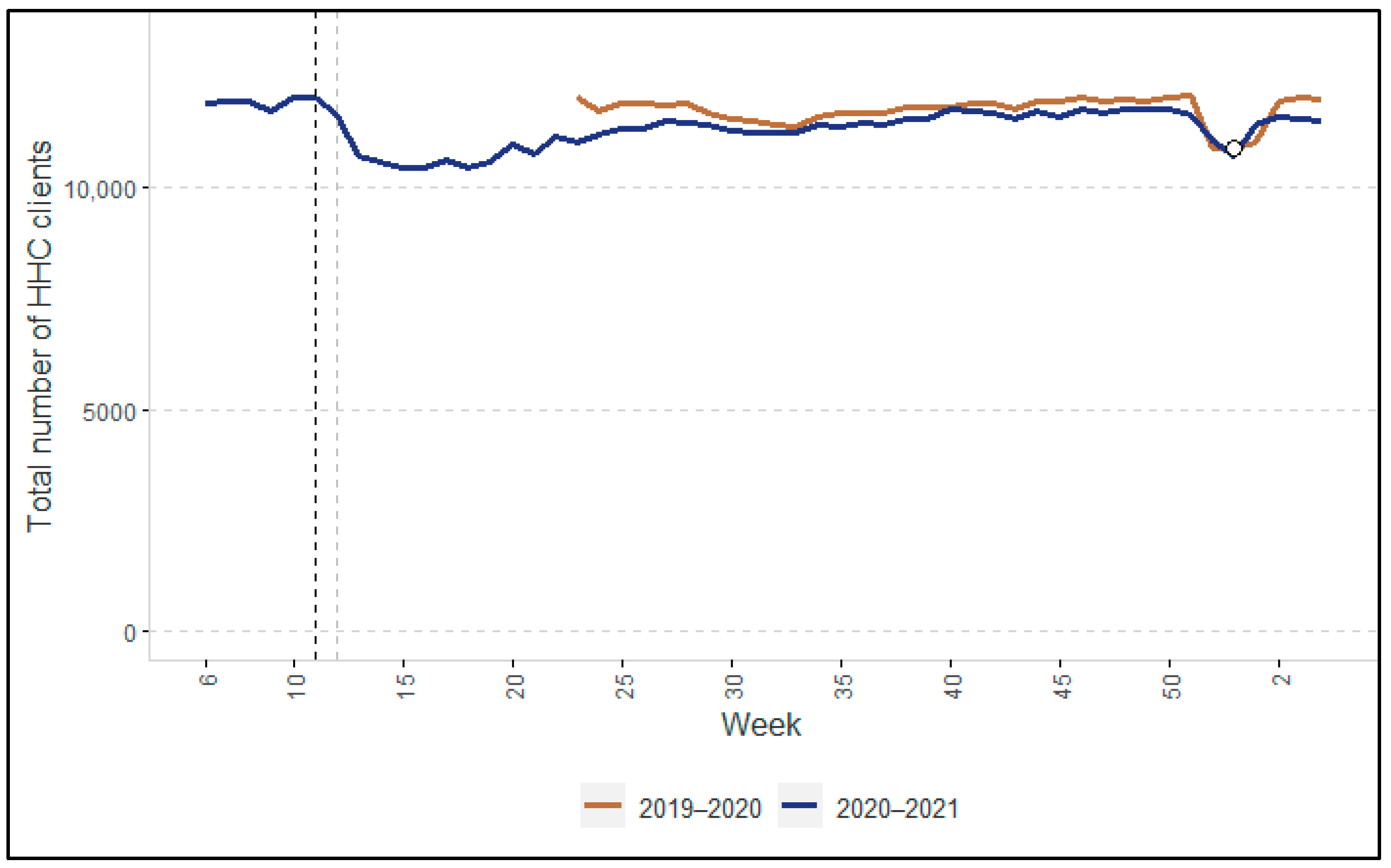

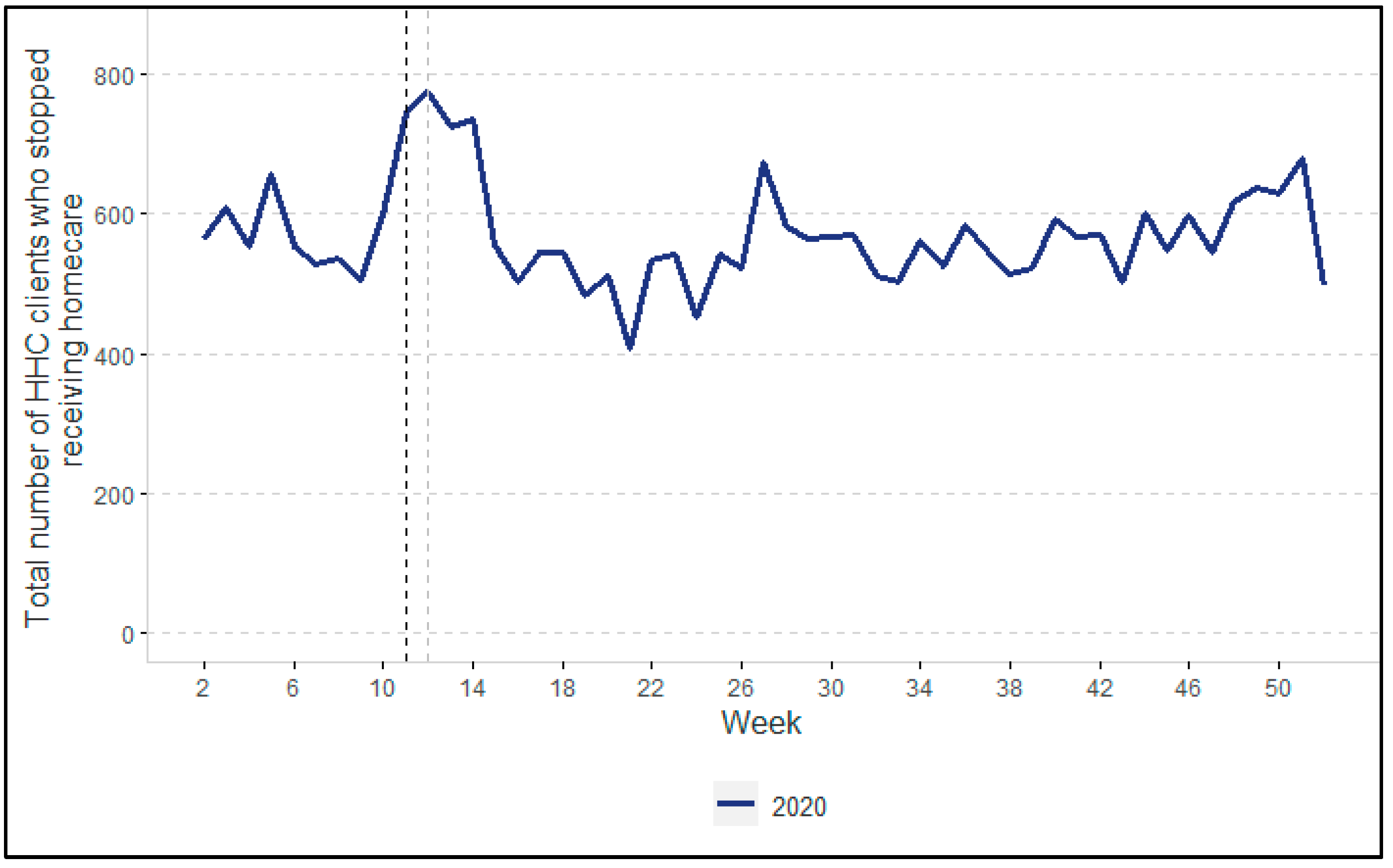

3.1.2. Changes in the Number of HHC Clients

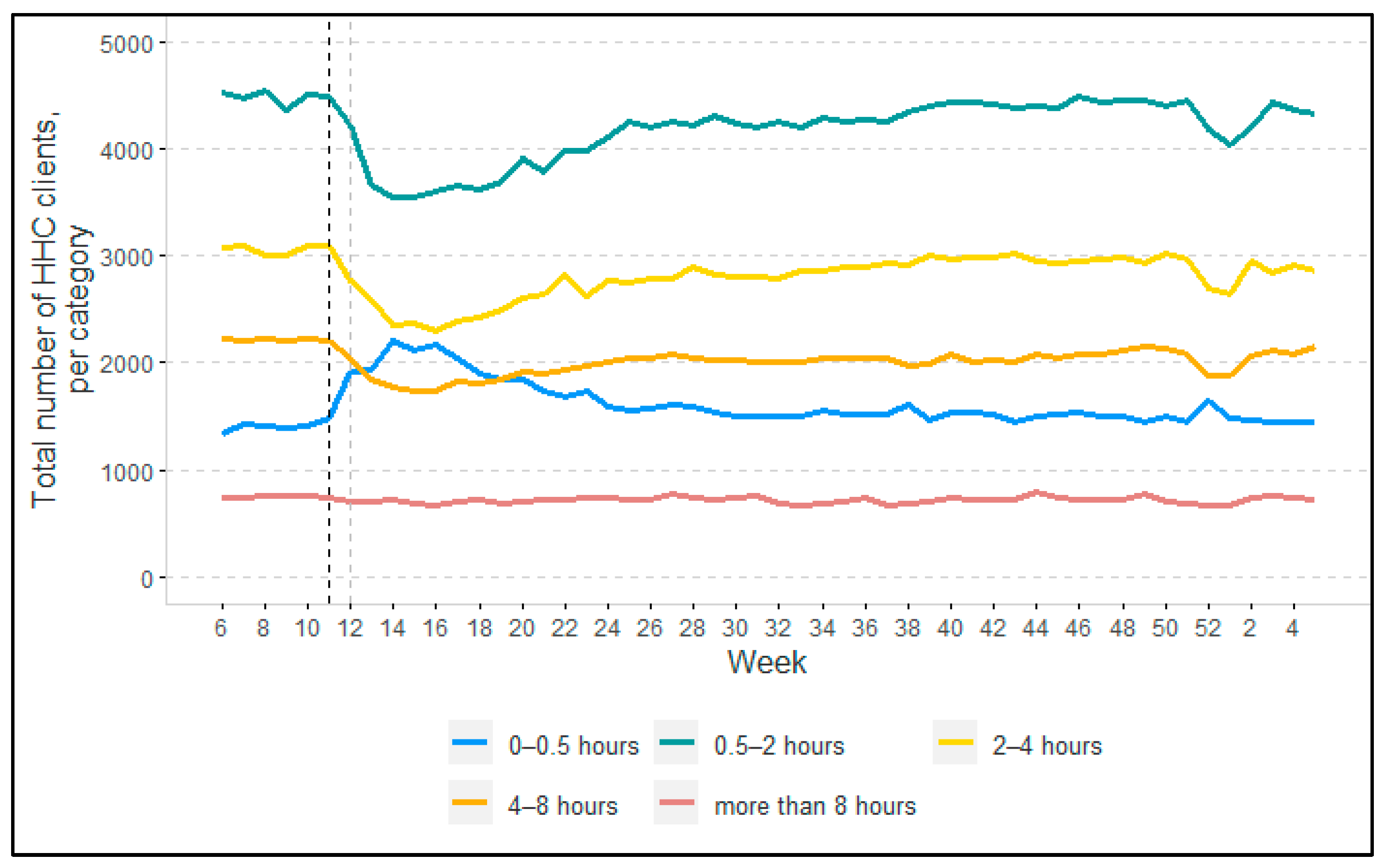

3.1.3. Changes in HHC Intensity of Clients

3.2. Providing and Receiving HHC during a Crisis

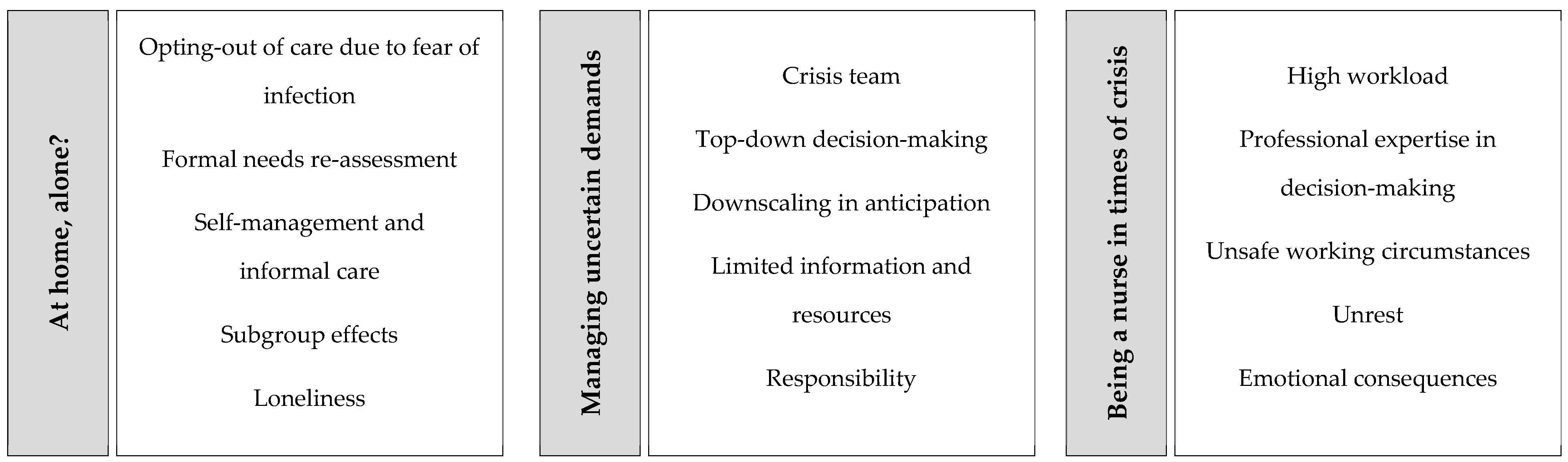

3.2.1. Theme 1: At Home, Alone?

“I have the impression that scaling back care was discussed properly with the clients and informal caregivers. They really have a say in that, resulting in a genuine dialogue [between the client, informal caregiver, and the nurse about scaling back care] that resulted in a solution.” (client council member D4a)

“As a district nurse, when you carry out a needs assessment you always look at […] how a client could become more independent, but not every client is open to that. Now [during the pandemic], clients were much more receptive.” (manager A2a)

“A few weeks after care was scaled back, we had informal caregivers contacting us saying: ‘I said I could take over [the care for the client], but I am having a tough time’.” (director D1a)

“[Due to the COVID-19 pandemic,] the daily routine for clients with dementia has changed, making them more depressed, confused, and lonely. That does not necessarily mean that they need to be admitted to a nursing home, but we are doing a lot to help these clients”. (district nurse B2b)

3.2.2. Theme 2: Managing Uncertain Demands

“HHC professionals couldn’t see the wood for the trees, and neither could we as managers when we were getting 80 e-mails just about ever-changing COVID-19 policies.” (crisis team member C2a)

“In the first wave, we had no idea what to expect, so we developed and introduced scenarios for scaling back, because we thought we might not have enough HHC personnel available. But actually the situation wasn’t as bad as expected for us.” (crisis team member C2a)

“For clients whose care provision was scaled back, our organization made sure they had weekly telephone contact with them to support them as well as possible.” (client council member B4b)

“Based on the numbers [of infections] in our region, we expected a huge wave of clients [to be discharged from the hospital] who would need HHC. From all sides, we were being told: ‘Get ready for [clients coming out of the] hospitals, scale back your care!’ However, this huge wave never came. […] Looking back, we scaled back more than was strictly necessary, but nobody knew that at the time. […] You assumed that [the need to scale back care] would only last for a few weeks, and that we’d manage it.” (director D1a)

“[Our HHC professionals] felt extremely unsafe, and there was nothing we could do about it because the resources just weren’t there. […] As a manager, I found that very difficult.” (manager A1a)

“At a certain point, we [our organization] bought PPE ourselves because we weren’t getting anything from the regional distribution of equipment. […] That degree of divergence between organizations—that shouldn’t be allowed to happen in my opinion.” (director C1a)

3.2.3. Theme 3: Being a Nurse in Times of Crisis

“We received feedback from our employees that they felt there was a major gap between them and their managers in the first wave. So in the second wave, […] we introduced all sorts of initiatives for our employees to be more involved in decision making on our policy.” (manager A2a)

“I received many phone calls in my own time, from colleagues asking for help or telling me about clients who were infected. […] I was constantly thinking about who was or might be infected, who could come out of quarantine, etc. […] And arranging for clients to be tested for COVID-19 by their GP took up a lot of my time.” (district nurse D3a)

“As employees, we were obliged to go to work, even if you had a family member at home who had tested positive for COVID-19. I felt pressure because of that.” (district nurse D3a)

“[The level of unrest during the second wave] was different in each team. Some teams said: ‘We have PPE now. We know who has tested positive and what to do.’ But other teams still panic a little if a client tests positive, wondering ‘What should we do now?!’” (policy advisor B2a)

“Some of my colleagues believe that they infected clients. They still have that on their mind and it’s a source of stress, and as a result they are currently on sick leave.” (district nurse C3b)

“[In the second wave,] the capability to carry the burden [of the COVID-19 pandemic] was lower compared to the first wave, but we all still just got on with it.” (manager A1a)

“When I see how everything is going now, I wonder how the next wave will turn out. […] [The HHC organizations] made it through the second wave, but whether it will continue to work and whether they have the resilience to absorb the next hit… I find that a frightening thought to be honest.” (client council member D4a)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iyengar, K.; Mabrouk, A.; Jain, V.K.; Venkatesan, A.; Vaishya, R. Learning opportunities from COVID-19 and future effects on health care system. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020, 14, 943–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, A.; Maclagan, L.C.; Schumacher, C.; Wang, X.; Jaakkimainen, R.L.; Guan, J.; Swartz, R.H.; Bronskill, S.E. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Home Care Services Among Community-Dwelling Adults With Dementia. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 2258–2262.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurits, E.E.M. Autonomy of Nursing Staff and the Attractiveness of Working in Home Care; University of Utrecht: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Genet, N.; Boerma, W.; Kroneman, M.; Hutchinson, A.; Saltman, R.B. Home Care across Europe; World Health Organization and NIVEL: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vektis Intelligence, Factsheet Wijkverpleging. Available online: https://www.vektis.nl/intelligence/publicaties/factsheet-wijkverpleging#Kaart_Wijkverpleging (accessed on 16 December 2021).

- Kroneman, M.; Boerma, W.; van den Berg, M.; Groenewegen, P.; de Jong, J.; van Ginneken, E. Health Systems in Transition: The Netherlands; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brocard, E.; Antoine, P.; Mélihan-Cheinin, P.; Rusch, E. COVID-19′s impact on home health services, caregivers and patients: Lessons from the French experience. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2021, 8, 100197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osakwe, Z.T.; Osborne, J.C.; Samuel, T.; Bianco, G.; Céspedes, A.; Odlum, M.; Stefancic, A. All alone: A qualitative study of home health aides’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York. Am. J. Infect. Control 2021, 49, 1362–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afschalen Wijkverpleging: Wat Heeft Deze Cliënt Écht Nodig? Available online: https://www.venvn.nl/nieuws/afschalen-wijkverpleging-wat-heeft-deze-client-echt-nodig (accessed on 6 September 2021).

- Sama, S.R.; Quinn, M.M.; Galligan, C.J.; Karlsson, N.D.; Gore, R.J.; Kriebel, D.; Prentice, J.C.; Osei-Poku, G.; Carter, C.N.; Markkanen, P.K.; et al. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Home Health and Home Care Agency Managers, Clients, and Aides: A Cross-Sectional Survey, March to June, 2020. Home Health Care Manag. Pr. 2021, 33, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IGZ. Verpleging, Verzorging en Thuiszorg Tijdens de Coronacrisis; Inspectie Gezondheidszorg en Jeugd: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; SAGE Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006; pp. 58–88. [Google Scholar]

- Elissen, A.M.J.; Verhoeven, G.S.; De Korte, M.H.; Bulck, A.O.E.V.D.; Metzelthin, S.F.; Van Der Weij, L.C.; Stam, J.; Ruwaard, D.; Mikkers, M.C. Development of a casemix classification to predict costs of home care in the Netherlands: A study protocol. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e035683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carlsen, B.; Glenton, C. What about N? A methodological study of sample-size reporting in focus group studies. BMC Med Res. Methodol. 2011, 11, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Markkanen, P.; Brouillette, N.; Quinn, M.; Galligan, C.; Sama, S.; Lindberg, J.; Karlsson, N. “It changed everything”: The Safe Home Care qualitative study of the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on home care aides, clients, and managers. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vislapuu, M.; Angeles, R.C.; Berge, L.I.; Kjerstad, E.; Gedde, M.H.; Husebo, B.S. The consequences of COVID-19 lockdown for formal and informal resource utilization among home-dwelling people with dementia: Results from the prospective PAN.DEM study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vernet Factsheet VVT Q1–2021. Available online: https://www.aovvt.nl/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/k211_VernetFactsheet.pdf. (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- MacLeod, S.; Tkatch, R.; Kraemer, S.; Fellows, A.; McGinn, M.; Schaeffer, J.; Yeh, C.S. The impact of COVID-19 on informal caregivers in the US. Int. J. Aging. Res. 2021, 4, 87. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, M.C.; Liu, Y.; Baumbach, A. Impact of COVID-19 on the Health and Well-being of Informal Caregivers of People with Dementia: A Rapid Systematic Review. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2021, 7, 23337214211020164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappa, S.; Ntella, V.; Giannakas, T.; Giannakoulis, V.G.; Papoutsi, E.; Katsaounou, P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raudenská, J.; Steinerová, V.; Javůrková, A.; Urits, I.; Kaye, A.D.; Viswanath, O.; Varrassi, G. Occupational burnout syndrome and post-traumatic stress among healthcare professionals during the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Best Pr. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2020, 34, 553–560. [Google Scholar]

- Miguel-Puga, J.A.; Cooper-Bribiesca, D.; Avelar-Garnica, F.J.; Sanchez-Hurtado, L.A.; Colin-Martínez, T.; Espinosa-Poblano, E.; Anda-Garay, J.C.; González-Díaz, J.I.; Segura-Santos, O.B.; Vital-Arriaga, L.C.; et al. Burnout, depersonalization, and anxiety contribute to post-traumatic stress in frontline health workers at COVID-19 patient care, a follow-up study. Brain Behav. 2021, 11, e02007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rücker, F.; Hårdstedt, M.; Rücker, S.C.M.; Aspelin, E.; Smirnoff, A.; Lindblom, A.; Gustavsson, C. From chaos to control–experiences of healthcare workers during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic: A focus group study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giebel, C.; Hanna, K.; Cannon, J.; Eley, R.; Tetlow, H.; Gaughan, A.; Komuravelli, A.; Shenton, J.; Rogers, C.; Butchard, S.; et al. Decision-making for receiving paid home care for dementia in the time of COVID-19: A qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topriceanu, C.-C.; Wong, A.; Moon, J.C.; Hughes, A.D.; Bann, D.; Chaturvedi, N.; Patalay, P.; Conti, G.; Captur, G. Evaluating access to health and care services during lockdown by the COVID-19 survey in five UK national longitudinal studies. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e045813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miner, S.; Masci, L.; Chimenti, C.; Rin, N.; Mann, A.; Noonan, B. An Outreach Phone Call Project: Using Home Health to Reach Isolated Community Dwelling Adults During the COVID 19 Lockdown. J. Community Health 2021, 1–7, online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Fields, N.; Cassidy, J.; Kusek, V.; Feinhals, G.; Calhoun, M. Caring callers: The impact of the telephone reassurance program on homebound older adults during COVID-19. Home Health Care Serv. Q. 2021, 40, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Stakeholder Level | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Strategic | Tactical | Operational | Client |

| N = 4 | N = 6 | N = 11 | N = 7 |

| 3 directors 1 manager | 2 managers 2 policy advisors 1 crisis team member 1 team leader | 11 district nurses | 7 client council members |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

van den Bulck, A.O.E.; de Korte, M.H.; Metzelthin, S.F.; Elissen, A.M.J.; Everink, I.H.J.; Ruwaard, D.; Mikkers, M.C. In the Eye of the Storm: A Quantitative and Qualitative Account of the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Dutch Home Healthcare. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2252. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042252

van den Bulck AOE, de Korte MH, Metzelthin SF, Elissen AMJ, Everink IHJ, Ruwaard D, Mikkers MC. In the Eye of the Storm: A Quantitative and Qualitative Account of the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Dutch Home Healthcare. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(4):2252. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042252

Chicago/Turabian Stylevan den Bulck, Anne O. E., Maud H. de Korte, Silke F. Metzelthin, Arianne M. J. Elissen, Irma H. J. Everink, Dirk Ruwaard, and Misja C. Mikkers. 2022. "In the Eye of the Storm: A Quantitative and Qualitative Account of the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Dutch Home Healthcare" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 4: 2252. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042252

APA Stylevan den Bulck, A. O. E., de Korte, M. H., Metzelthin, S. F., Elissen, A. M. J., Everink, I. H. J., Ruwaard, D., & Mikkers, M. C. (2022). In the Eye of the Storm: A Quantitative and Qualitative Account of the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Dutch Home Healthcare. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 2252. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042252