Stress and Adjustment during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study on the Lived Experience of Canadian Older Adults

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Lived Experience of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Qualitative Findings

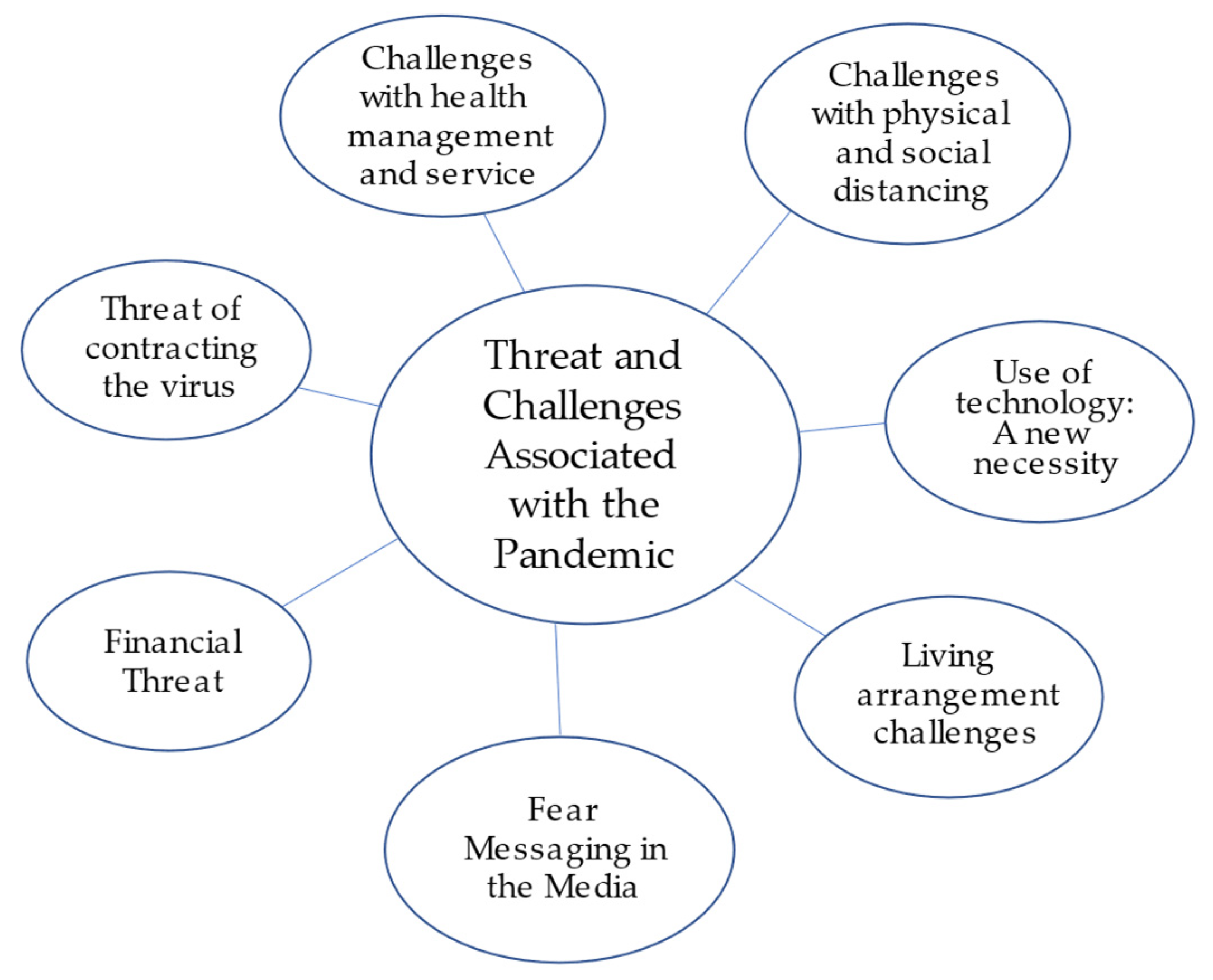

3.2.1. Theme 1: Threat and Challenges Associated with the Pandemic

Subtheme 1: Threat of Contracting the SARS-CoV-2 Virus

Subtheme 2: Financial Threat

Subtheme 3: Fear Messaging in the Media

Subtheme 4: Living Arrangement Challenges

Subtheme 5: Physical Distancing and Minimal Social Interactions

Subtheme 6: The Challenge of Health Management and Health Services

Subtheme 7: Use of Technology: A New Necessity

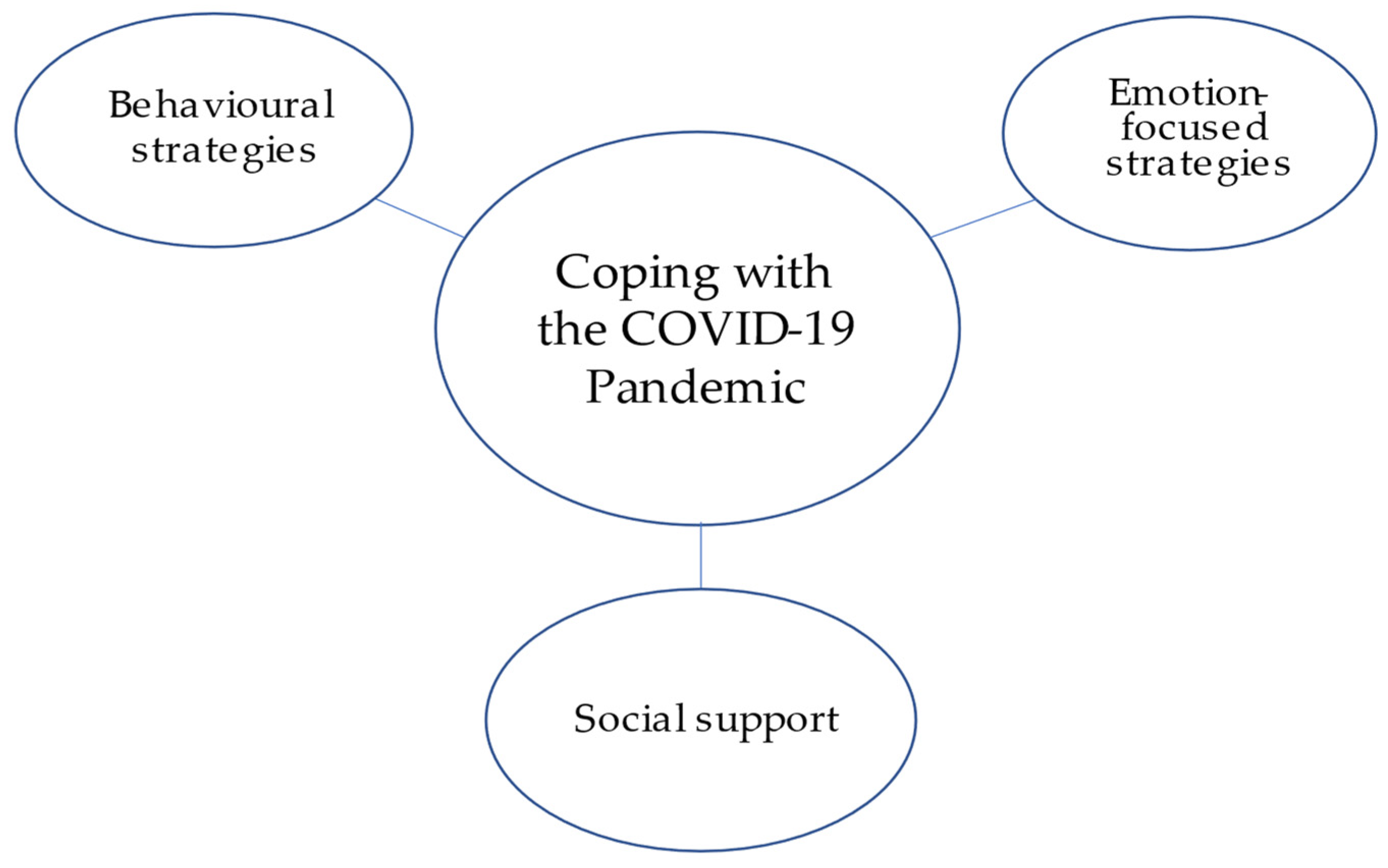

3.2.2. Theme 2: Coping with the COVID-19 Pandemic

Subtheme 1: Behavioral Strategies

Subtheme 2: Emotion-Focused Strategies

Subtheme 3: Social Support

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Government of Ontario. Report on Ontario’s Provincial Emergency from March 17, 2020 to July 24, 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/document/report-ontarios-provincial-emergency-march-17-2020-july-24-2020 (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Risk for COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalization, and Death by Age Group; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-age.html (accessed on 3 April 2021).

- Li, Y.; Ashcroft, T.; Chung, A.; Dighero, I.; Dozier, M.; Horne, M.; McSwiggan, E.; Shamsuddin, A.; Nair, H.; for the Usher Network for COVID-19. Risk factors for poor outcomes in hospitalised COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Glob. Health 2021, 11, 10001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanez, N.D.; Weiss, N.S.; Romand, J.-A.; Treggiari, M.M. COVID-19 mortality risk for older men and women. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, M.; McGarrigle, C.; Hever, A.; O’Mahoney Moynihan, S.; Loughran, G.; Kenny, R.A. Loneliness and Social Isolation in the COVID-19 Pandemic among the over 70s: Data from The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA) and ALONE. Trinity College Dublin: The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing. 2020. Available online: https://tilda.tcd.ie/publications/reports/Covid19SocialIsolation/ (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Douglas, H.; Georgiou, A.; Westbrook, J. Social participation as an indicator of successful aging: An overview of concepts and their associations with health. Aust. Health Rev. 2017, 41, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Golden, J.; Conroy, R.M.; Bruce, I.; Denihan, A.; Greene, E.; Kirby, M.; Lawlor, B.A. Loneliness, social support networks, mood and wellbeing in community-dwelling elderly. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2009, 24, 694–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirven, N.; Debrand, T. Social participation and healthy ageing: An international comparison using SHARE data. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 2017–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L.L.; Shavit, Y.Z.; Barnes, J.T. Age Advantages in Emotional Experience Persist Even Under Threat from the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 31, 1374–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Sanguino, C.; Ausín, B.; Castellanos, M.Á.; Saiz, J.; López-Gómez, A.; Ugidos, C.; Muñoz, M. Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Brain, Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Tilburg, T.G.; Steinmetz, S.; Stolte, E.; Van Der Roest, H.; De Vries, D.H. Loneliness and Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Study Among Dutch Older Adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2020, 76, e249–e255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czeisler, M.É.; Lane, R.I.; Petrosky, E.; Wiley, J.F.; Christensen, A.; Njai, R.; Weaver, M.D.; Robbins, R.; Facer-Childs, E.R.; Barger, L.K.; et al. Mental Health, Substance Use, and Suicidal Ideation during the COVID-19 Pandemic. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1049–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dionne, M.; Roberge, M.-C.; Brousseau-Paradis, C.; Dube, E.; Hamel, D.; Rochette, L.; Tessier, M. COVID-19—Pandémie, bien-être Émotionnel et Santé Mentale. Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec. 2020. Publication no: 3083. Available online: https://www.inspq.qc.ca/covid-19/sondages-attitudes-comportements-quebecois/sante-mentale-decembre-2020 (accessed on 3 December 2020).

- Losada-Baltar, A.; Jiménez-Gonzalo, L.; Gallego-Alberto, L.; Pedroso-Chaparro, M.D.S.; Fernandes-Pires, J.; Márquez-González, M. “We Are Staying at Home.” Association of Self-perceptions of Aging, Personal and Family Resources, and Loneliness with Psychological Distress during the Lock-Down Period of COVID-19. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2021, 76, e10–e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology: Vol. 2. Research Designs (57-71); Cooper, H., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Stainback, K.; Hearne, B.N.; Trieu, M.M. COVID-19 and the 24/7 News Cycle: Does COVID-19 News Exposure Affect Mental Health? Socius Sociol. Res. Dyn. World 2020, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falvo, I.; Zufferey, M.C.; Albanese, E.; Fadda, M. Lived experiences of older adults during the first COVID-19 lockdown: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparrow, E.P.; Swirsky, L.T.; Kudus, F.; Spaniol, J. Aging and altruism: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Aging 2021, 36, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahana, E.; Bhatta, T.; Lovegreen, L.D.; Kahana, B.; Midlarsky, E. Altruism, helping, and volunteering: Pathways to well-being in late life. J. Aging Health 2013, 25, 159–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hazel, M. Reasons for Working at 60 and Beyond. Labour Statistics as a Glance. Statistics Canada Catalogue no 71-222-X. 2018. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/71-222-x/71-222-x2018003-eng.pdf?st=--J9MrDK (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Linton, S.L.; Leifheit, K.M.; McGinty, E.E.; Barry, C.L.; Pollack, C.E. Association Between Housing Insecurity, Psychological Distress, and Self-rated Health Among US Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2127772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinlay, A.R.; Fancourt, D.; Burton, A. A qualitative study about the mental health and wellbeing of older adults in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, C.R.; Averill, J.R. Solitude: An Exploration of Benefits of Being Alone. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 2003, 33, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.S.; Shiba, K.; Boehm, J.K.; Kubzansky, L.D. Sense of purpose in life and five health behaviors in older adults. Prev. Med. 2020, 139, 106172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irving, J.; Davis, S.; Collier, A. Aging With Purpose: Systematic Search and Review of Literature Pertaining to Older Adults and Purpose. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2017, 85, 403–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afifi, T.D.; Basinger, E.D.; Kam, J.A. The extended theoretical model of communal coping: Understanding the properties and functionality of communal coping. J. Commun. 2020, 70, 424–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamm, M.A.; Brown, P.J.; Karp, J.F.; Lenard, E.; Cameron, F.; Dawdani, A.; Lavretsky, H.; Miller, J.P.; Mulsant, B.H.; Pham, V.T.; et al. Experiences of American older adults with pre-existing depression during the beginnings of the COVID-19 pandemic: A multicity, mixed-methods study. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2021, 28, 924–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Key Health Inequalities in Canada: A National Portrait; Public Health Agency of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/publications/science-research/key-health-inequalities-canada-national-portrait-executive-summary/hir-executive-summary-eng.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2021).

- Meisner, B.A.; Dogra, S.; Logan, A.J.; Baker, J.; Weir, P.L. Do or decline?: Comparing the effects of physical inactivity on biopsychosocial components of successful aging. J. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 688–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterbotham, S.; du Preez, J. Psychosocial wellbeing in active older adults: A systematic review of qualitative literature. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2015, 9, 96–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goethals, L.; Barth, N.; Guyot, J.; Hupin, D.; Celarier, T.; Bongue, B. Impact of Home Quarantine on Physical Activity among Older Adults Living at Home during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Qualitative Interview Study. JMIR Aging 2020, 3, e19007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, H.R.; Huseth-Zosel, A. Lessons in Resilience: Initial Coping among Older Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Gerontologist 2021, 61, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. Gratitude, like other positive emotions, broadens and builds. In The Psychology of Gratitude; Emmons, R.A., McCullough, M.E., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 145–166. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, J.; Lachman, M.; Wilson, C.L.; Nakamura, J.S.; Kim, E.S. The positive influence of sense of control on physical, behavioral, and psychosocial health in older adults: An outcome-wide approach. Prev. Med. 2021, 149, 106612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.; Chun, S.; Lee, S.; Lee, K.H.; Kim, J. Internet Use and Well-Being in Older Adults. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2015, 18, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipolletta, S.; Gris, F. Older people’s lived perspectives of social isolation during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, B.R.; Ferrucci, L.; Zonderman, A.B.; Slade, M.D.; Troncoso, J.; Resnick, S.M. A culture-brain link: Negative age stereotypes predict Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers. Psychol. Aging 2016, 31, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meisner, B.A.; Levy, B.R. Age stereotypes’ influence on health: Stereotype Embodiment Theory. In Handbook of Theories of Aging, 3rd ed.; Bengtson, V., Settersten, R., Eds.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Chapter 14; pp. 259–276. [Google Scholar]

- Raphael, D. A discourse analysis of the social determinants of health. Crit. Public Health 2011, 21, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Descriptive Variable | Mean (SD, Range) or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 72 (4.78, min 65–max 81) |

| Sex (% female) | 13 (59) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Caucasian/European | 18 (82) |

| Black | 1 (5) |

| Asian | 2 (9) |

| Middle Eastern | 1 (5) |

| Relationship Status | |

| Married | 13 (59) |

| Common Law | 1 (4) |

| Single | 6 (27) |

| Widow | 2 (9) |

| Living Arrangement | |

| Alone | 6 (27) |

| Spouse | 12 (55) |

| Spouse and Children | 2 (9) |

| Other family | 2 (9) |

| Place of Residence | |

| House/Townhouse Owned | 10 (45) |

| Condominium (Owned unit) | 7 (32) |

| Apartment (Rental unit) | 3 (14) |

| Group Housing | 2 (9) |

| Caregiver Status | |

| Not Caregiver | 18 (81) |

| Primary Caregiver | 2 (9) |

| Secondary Caregiver | 2 (9) |

| Socioeconomic Status | |

| Low | 1 (5) |

| Medium Low | 6 (27) |

| Medium | 7 (32) |

| Medium High | 6 (27) |

| High | 1 (5) |

| Prefer not to say | 1 (5) |

| Religion | |

| Christianity | 6 (27) |

| Buddhism | 1 (5) |

| Judaism | 7 (32) |

| Spiritual | 5 (23) |

| Not religious | 3 (14) |

| General Health Status | |

| Poor | 1 (5) |

| Fair | 2 (9) |

| Good | 7 (32) |

| Very good | 8 (36) |

| Excellent | 4 (18) |

| Existing Medical Conditions | |

| No | 7 (32) |

| Yes | 15 (68) |

| PHQ-9 score | 4.27 (4.78, 0–17) |

| Worry for SARS-CoV-2 contraction | 3.93 (1.52, 1–6.5) |

| Theme 1: Threat and Challenges Associated with the Pandemic | |

|---|---|

| codes | Subtheme 1: Threat of Contracting the SARS-CoV-2 Virus |

| Low worry (good health) | I’m really not that concerned if I catch it, I catch it, I’m hopeful that I would be able to pull through. I have a fairly good immune system when I get a cold. I do have asthma, and when I get a cold, it does flare it up, but I’ve always managed to control it so it’s not severe enough that it really would worry me. (#14, 70 y/o Irish Jewish female, lives with spouse in condominium) |

| Low worry (good health) | Compared to others of my age, I feel that I will not be affected by the virus. I won’t get it. (#1, 75 y/o Filipino male, lives with spouse and children in townhouse) |

| Low worry (good health) | Well even though technically I’m a diabetic, because I’m now exercising much more frequently, I’m now feeling fitter than I have ever done for 20 years. You know, I’m feeling fitter than I was in the mid-50s, so it’s just remarkable…even though technically I should be at risk, but the reality is that I’m feeling quite fit. (#13, 73 y/o Jewish male, lives with spouse in a condo) |

| Low worry (taking precautions) | I’m not worried about getting the virus. If I take appropriate precaution I think it’s practically zero…it’s unlikely that I’m going to get the virus unless someone I come in contact with has it and I break the rules. (#12, 70 y/o Caucasian male, lives with spouse in a house) |

| Low worry (taking precautions) | Well, I’m taking precautions, all the precautions like wearing face masks and washing my hands. We’re changing the hand towels much more frequently and we use our own separate hand towels. We’re taking these types of precautions to try to preserve ourselves. (#13, 73 y/o Jewish male, lives with spouse in a condo) |

| Low worry (taking precautions) | I think [the recommended safety practices] are a precaution that’s necessary. I think we have something we can do to make us feel more secure. I put coffee filters in my in my mask too and I change those to keep them affective, to keep the mask effective. (#7, 81 y/o Caucasian male, living with same-sex spouse in an apartment) |

| Infrequent worry | I try and take all the necessary precautions… but at the same time I do hear people get the COVID and they cannot figure out how they get it, so that can get me a little uneasy sometimes but it’s not something I worry about, but in the back of my head I’m always saying well OK I’m doing everything right and everything I’m supposed to do, I hope that’s good enough for me not to get COVID. (#18, 78 y/o Black female, lives alone in a house) |

| Infrequent worry | Because I have an autoimmune disease and I have a disability and stuff, I’m more vulnerable than if I was 25 years old. I have to be more cautious and you know make sure that I’m following the social isolating, and washing my hands a lot, wearing the masks because, with the illness that I have I’m never going to be able to have the vaccine, because I got my illness from having a vaccine from the flu shot, so I have to really protect myself from getting COVID. (#8, 71 y/o Caucasian female, lives with family in group housing) |

| Infrequent worry | Say I’m having a bit of nausea because of my stomach surgery, sometimes I think ‘Oh my God am I getting COVID’ and then when I wake up I say ‘no no no it’s unlikely’. (#10, 72 y/o Celtic Jewish female, lives with family in group housing) |

| Concern for others | My daughter’s job has been affected you know like 100%. I mean it’s amazing the changes she’s had to go through and right from the very beginning, she is in a very vulnerable job which has been a worry you know, she’s more exposed from frontline workers. (#13, 73 y/o Jewish male, lives with spouse in a condominium) |

| Concern for others | I’m glad that I found that [cloth mask] because I feel protected and I’m protecting other people from me too because, my mouth is paralyzed and a lot of times spit will come out of my mouth unintentionally, so I’m protecting other people when I’m out too… I have a good social conscience, I don’t want to make anybody else sick and I don’t want to get sick. (#8, 71 y/o Caucasian female, lives with family in group housing) |

| Concern for others | We’re also more careful because his [husbad] immune system is shot for the next two years and then me too, like being able to go see my mom. She’s 98 right, so not being able to go to the nursing home and having to worry about her… if I can go there I gotta be more careful as to where I go or who I see because I could be bringing it [the virus] to them. (#4, 69 y/o Caucasian female, lives with spouse in a house) |

| Frustration with others | From what I see everybody’s following the rules, where it’s the young people who don’t seem to get it… They don’t seem to take it as seriously. I’ve noticed other people’s kids, in their 20s as well, jumping into cars with their friends and driving off, and I’m thinking ‘oh my god’. (#22, 65 y/o Caucasian female, lives with spouse in a house) |

| Frustration with others | I’m a little bit annoyed that some people think that they shouldn’t do it [i.e., follow safety recommendtations] because of their own individual rights and, you know, it’s just silly. I mean it’s something in a case like this, I think individual rights get suspended and you have to do the right thing for everybody else. (#3, 67 y/o Caucasian female, lives alone in a house) |

| Frustration with others | When it’s clear that distancing, washing hands, wearing a mask and not gathering in large groups works, why people on God’s green earth think that they can be doing this appalls me. (#16, 70 y/o Jewish male, lives with common law partner in a condominium) |

| Frustration with others | What pisses me off is when I go grocery shopping, there are a lot of shoppers who don’t wear their mask, or if they do it under their chin or below their nostrils. That really pisses me off. (#11, 74 y/o Jewish male, living with spouse in a condominium) |

| Fear for continued pandemic | I fear that the virus is going to continue… that we’re not going to find a way to deal with it, like we’re not going to find a vaccine early enough and the that this will just go on. (#15, 65 y/o Ukrainian female, living alone in a house) |

| Fear for continued pandemic | I worry we will get a second wave, and it won’t be in the fall, it will come this summer. And then we’ll get a third wave. I guess that it will be never ending. (#22, 65 y/o Caucasian female, lives with spouse and children in house) |

| Fear for continued pandemic | I worry that things will not be as they were, that we won’t go back, where there’s going to be a total new normal in terms of traveling and being able to see people and be comfortable with people. I think that’s my biggest concern, that just things will not be as they were. (#6, 71 y/o Caucasian female, lives alone in a house) |

| codes | Subtheme 2: Financial Threat |

| Housing | My biggest concern... that financially I can stay in my apartment, and I can afford it. (#2, 74 y/o Caucasian female, widow lives alone in a condominium) |

| Standard of living | My biggest concern is probably financial because I worry that my husband still works as a [occupation] and he needs to go to see clients and the clients aren’t as busy. I am 70, they wouldn’t employ me any longer and it’s not, I mean, I worked as a [profession], I haven’t lost that ability, but they just don’t see it… in that sense, that bit upsets me and so I have to rely on my husband’s income and on our pensions, and that it’s tough. It’s tough to live in a fixed income these days. (#14, 70 y/o, Irish Jewish female, lives with spouse in a condominium) |

| Financial stability | I’m a sole practitioner and at least for April and the beginning of May my work suffered terribly it was very challenging in terms of income and the word I use is discombobulating in terms of working a little bit at home, sometimes at home, sometimes in the office, and that was really challenging. (#16, 70 y/o Jewish male, lives with common law partner in a condominium) |

| Financial stability | I have a financial concern, because I’m semi-retired…so I don’t get pension income… and I’m concerned since my employment income is significantly lower than it was at this point last year. And I have taken advantage of the government’s subsidies…but you know that’s finishing this month. (#13, 73 y/o Jewish male, lives with spouse in a condominium) |

| codes | Subtheme 3: Fear Messaging in the Media |

| Fear messaging | I as a CNN junkie. I’m now not doing that because I don’t think that’s healthy either… I know fear of catching the virus is fueled by media coverage because now that I don’t listen to it, like very little, I’m much happier. Yeah. I think at first it was just like it was like an addiction. (#5, 74 y/o Caucasian female, lives with spouse in a house) |

| Fear messaging | Every time I watched the news I would just feel my heart sink a bit … I wanted to stay informed as best I could, but I found that it just got to be too much so I limited it to twice a day probably. (#6, 71 y/o Caucasian female, lives alone in a house) |

| Fear messaging | I think the media has a lot to do with people’s fears… I think sometimes that the media plays it up. So sometimes it’s good not to watch the news … we’re trying very hard not to get too excited about this whole thing. (#9, 73 y/o Caucasian male, living with spouse in a house) |

| Ageist fear messaging | When it all first came out... a lot of what we heard was that it was going to affect ‘us’ more than anyone else, and that played on my brain a little bit…. all you heard was ‘be careful of the’, you know, ‘it’s the seniors’. (#5, 74 y/o Caucasian female, lives with spouse in house) |

| Ageist fear messaging | All we heard was it definitely is going to impact people over the age of 65 or 70, and stay home. Basically, we don’t have enough ventilators for you folks—you need to flatten the curve because you’re the ones that are really going to put a stress on the system. I had a social obligation. Like, even if I did poke my head out the door it’s like ‘Oh my gosh people are going to know I’m over 65′ and they’re going to probably look down on me because I’m not in my house. So, for a while I was afraid to go out for a walk even. (#6, 71 y/o Caucasian female, lives alone in a house) |

| Ageist fear messaging | Everybody says that if you’re 60 or older you are more in danger. I don’t believe in living my life in fear. I mean, I know that I’m 70, but in reality most of the time, other than with my arthritis, I don’t feel any different than I did when I was bringing my kids up… And my age doesn’t, as far as I’m concerned… it’s only a number. (#14, 70 y/o, Irish Jewish female, lives with spouse in a condominium) |

| Media lacking | Because [friend] is on the task force, we’re getting a lot of real information that the general public doesn’t get… and yes this thing is very contagious, but using proper care is not a big deal. I think sometimes that the media plays it up. So sometimes it’s good not to watch the news. (#9, 73 y/o Caucasian, male living with spouse in a house) |

| Media lacking | I’m just saying, when it comes to the health of the older people, they will tell you OK stay at home, do this… but nobody tells you, OK should you get more vitamins, should you eat this, or don’t eat that… you don’t hear that. (#18,78 y/o Black female, lives alone in a house) |

| Media lacking | I find that the news is not really giving us good information…we are finding that the information is not very clear at all, even with government websites, certainly not in the newspapers. (#13, 73 y/o Jewish male, lives with spouse in a condominium) |

| codes | Subtheme 4: Living Arrangement Challenges |

| Living alone | Even if something small broke down like my smoke detector… it started beeping and I couldn’t get anybody to come in to take the stupid thing down and put in a new one because no one was coming into the house and that was true for anything really, anything that you needed done. It’s very much that feeling of helplessness. (#15, 65 y/o Ukrainian female, lives alone in a house) |

| Living alone | That’s the biggest thing for me is that living alone I have quite frankly started to name the spiders in my house. I don’t really have a bubble. So that’s the thing that I’m kind of missing. That everybody has made, created these little bubbles with their immediate family, ‘cause those are the people that they really need. They need to bubble with, and I totally get that, but when I don’t really have family in the city, it’s harder for me to have a bubble. And that’s the thing that I have found the hardest. (#3, 67 y/o Caucasian female, lives alone in a house) |

| Living with spouse | People in our condo who are widowers, and some of them have trouble coping with being alone. So even though we’re not together all the time in the condo, we’re in our separate rooms at times, you know that person is there, and you can discuss what you like about what they’re showing on [TV show] or things like that, or have a friendly competition of answering the Jeopardy questions. (#11, 74 y/o Jewish male, lives with spouse in a condominium) |

| Living in small space | We’re more cross with each other and I think that’s just inevitable. we’re together 24 h a day, most of the time, and that’s too much for anybody. (#7, 81 y/o Caucasian male, lives with same-sex spouse in an apartment) |

| Living in small spaces | If you catch the virus, you need to quarantine yourself. But because of the construction of our townhouse. If one of us catches it, well then the person has to quarantine. But what about the other two? They might be in danger of catching the virus. (#1, 75 y/o Filipino male, lives with spouse and children in a house) |

| Living in large spaces | We’re not in a one-bedroom apartment, we’re in this large house that we share. We’re in the fortunate group that can do that, if I want to hide from her, I can go hide—if she needs to hide from me she can. I can hide out in the backyard…(#12, 70 y/o Caucasian male, lives with spouse in a house) |

| Living in large spaces | We’ve got a big backyard, we’re back on a ravine, so we’ve got privacy back there, we can go sit back there. We tend to sit out front, decked out front as well because the neighbors walk by and you talk to people. And its big enough so that we can have someone on the deck and still be social distanced by 6 feet. Which we do. (#22, 65 y/o Caucasian female, lives with spouse in a house) |

| codes | Subtheme 5: The Challenge of Physical Distancing and Minimal Social Interactions |

| Missing social groups | Gone are the days sitting around eating a meal, going to the movies, all that stuff. I mean, normally we would like to get together, go for a walk, or a swim, and then go eat or have a coffee, and we would walk in the valley or somewhere nice. That’s gone. (#20, 67 y/o Caucasian female, lives with spouse in a condominium) |

| Missing social groups | Social distancing, I think, is probably the one that has affected me more because I cannot go out with my friends, we can’t gather together…it makes me a little sad that the things I used to do, go out and have a cup of tea or coffee with my friends, I cannot do that. Before COVID, maybe three or four of us will go for a coffee or we go for lunch or we do things together, and I enjoy that very much. (#18 78 y/o Black female, lives alone in a house) |

| Missing social groups | All my social interactions like my group that I’m involved with and volunteering at [institution] is all cancelled so that was kind of hard because you don’t have any social outlets that way. (#2, 74 y/o Caucasian female, widow lives alone in a condominium) |

| Missing social groups | I want to go to a restaurant and eat with other people. That’s my biggest thing now. Yeah I’m dying- and I want to get out of the city. I don’t have a car. So it’s more difficult for me to get out. And even if I get out, you know, where would I go because I don’t know, you know, just because Toronto is still been kind of a hot spot. And a lot of my friends have cottages. So they just disappear for the summer. And usually I get invited to the cottage… but now, they’re kind of isolating themselves at cottages. (#3, 67 y/o Caucasian female, lives alone in a house) |

| Missing places of worship | Before the pandemic, I was in the synagogue twice a day and, you know, communing with a group of people… but some of it has had to be completely cancelled and I will say I have adapted, but it’s still a big change in my circumstances. (#13, 73 y/o Jewish male, lives with spouse in a condominium) |

| Missing places of worship | I was an usher in my church but I have given it up. Ushering is something that I really like to do and chit chat with people at the back of the church, and yeah I think in a sense I have missed that. (#18, 78 y/o Black female, lives alone in a house) |

| Missing places of worship | I miss going to church, I’ll be honest. But they did open our parish and I chose not to be one of the ones that went back. I don’t think it’s time. I think it’s too soon. I can watch it online. It’s not as good, but it certainly helps. So that’s a big part of my life because I’m very strong Catholic. (#5, 74 y/o Caucasian female, lives with spouse in a house) |

| Missing family | We cannot see our grandchildren up close and personal because, well because they [the parents] don’t want us, they don’t want to risk our being with the kids… it’s been an emotional loss exacerbated by the COVID thing. (#7, 81 y/o Caucasian male, lives with same-sex spouse in an apartment) |

| Missing family | Psychologically we’re missing our contact with our family…I’ve got grandchildren, my son, his wife is strict over the whole rules and she hasn’t stepped foot in our house since March… I wouldn’t say it’s me being depressed or anything but it’s disappointing. (#13, 73 y/o Jewish male, living with spouse in a condominium) |

| Missing family | I can’t go and hug my own grandchildren… It really upsets me a lot that my grandchild doesn’t know us and he’ll never really know us the way my grand-daughters do because he doesn’t see us. (#14, 70 y/o, Irish Jewish female, lives with spouse in a condominium) |

| Need for human contact | Now, I’m a hugger. It’s painfully hard for me to not run up and throw myself all over someone. I can do the elbow thing now. I’m learning. This is a day-by-day thing I will not lie. I’m not ashamed to say this. I have gone in the bedroom after the bed is all made later in the day and that [body] pillow is there and I have actually laid down and I’ve hugged it and I’m not ashamed to say that. And there is a little bit of comfort and, you know what, you take what you can get. Sounds ridiculous, but whatever works. Everybody should have a pillow. (#5, 74 y/o Caucasian female, lives with spouse in house) |

| Need for human contact | I’ve never really considered myself like a really overly affectionate person but I’m just really, you know, I’ve been out now for a massage and I went and had my nails done yesterday and I had my hair done last week and it’s like just to have another person touch me has been fantastic! (#3, 67 y/o Caucasian female, lives alone in a house) |

| Need for human contact (emotional wellness) | Not being able to see my friends has made it harder for managing my post-traumatic stress… I have to be very careful about what I read and what I watch on movies or TV or whatever, that it doesn’t trigger me so being in COVID and not being able to see some of the people that I miss has made it a little harder. (#8, 71 y/o Caucasian female, lives with family in group housing) |

| Life event | Well, I live on my own now, which is a big change. So that’s an adjustment for me because cooking for one… and what I do is I put the radio on as soon as I wake up, and that helps because somebody is talking, you know? I’m so happy for my radio. [My husband] didn’t die of COVID-19 it was just his heart gave out, you know? In the hospital, I could not visit because of the COVID and so his decision was to have palliative care, which in a way was really good because he was with me, you know? … I make sure I have a distance which is kinda sad in a way, but that’s the way it is right, can’t be hugging anybody… I find that very hard especially after a loss you know. (#2, 74 y/o Caucasian female, lives alone in a condominium) |

| Life event | My wife was admitted to hospital and for 12 days I couldn’t visit her... I was worried and I worried that she was feeling lonely, but then the procedure she had had a positive effect on her health so I’m glad with the end result. (#17, 77 y/o Middle Eastern male, lives with spouse in condominium) |

| Life event | And during that week I was supposed to have a retirement party—three of them scheduled for the last week. And so when I went home, everything was cancelled. I didn’t get to say goodbye to my friends. Some of them probably didn’t even know I was retired. Everything just went poof and it was gone. (#1, 75 y/o Filipino male, lives with spouse and children in house) |

| Not missing it | In a way it doesn’t bother me as much because I like being on my own sometimes, and quiet, and I don’t need interaction constantly. I’m just happy to be with me. (#2, 74 y/o Caucasian female, widow lives alone in a condominium) |

| Not missing it | My social sphere is restricted dramatically…my life isn’t noticeably worse because I don’t get to spend a couple afternoons at the senior centre. Now for some people though, that’s their whole world, and they’re there every day all day long. (#12, 70 y/o Caucasian male, lives with spouse in a house) |

| codes | Subtheme 6: The Challenge of Health Management and Health Services |

| Maintaining health routine | I am a member of the [community center] and that was my outlet for exercise [for my scoliosis]. I went to three-to-five classes for aquafit and I swam approximately a mile a week—that’s gone. So I’ve been more than half a year without this wonderful exercise that made me feel a lot more energetic than I am now. (#7, 81 y/o Caucasian male, lives with same-sex spouse in an apartment) |

| Transient health concern | For a couple of weeks ago I was having some difficulty sleeping and I actually talked to my doctor about it and she had suggested that I try melatonin. … I think it was just, not stress so much as just feeling tired of the sameness of it all. You know, just worn down a little bit. (#3, 67 y/o Caucasian female, lives alone in a condominium) |

| Exacerbation of existing symptoms | You still get the intrusive thoughts [obsessive compulsive disorder] but you don’t have to act on them. But I noticed it has been exacerbated during this pandemic. (#20, 67 y/o Caucasian female, lives with spouse in a condominium) |

| Exacerbation of existing symptoms | The fact that I have some anxiety, certainly the anxiety intensified because I didn’t have the systems to be able to talk to. (#6, 71 y/o Caucasian female, lives alone in a house) |

| Health services | I used to go just over half a block away and go see my doctor and get appointments within the week and now you have to go through all these gatekeepers, you have to go through somebody on the phone that doesn’t know you, and then I talked to the nurse who does know me and then she talked to the doctor and, you know, so it’s levels and levels of bureaucracy to get to your doctor. (#10, 72 y/o Celtic Jewish female, lives with family in group housing) |

| Health services | One of thing that I find really frustrating is that I cannot see a doctor [for chronic pain condition]. I can have a telephone appointment, but what I needed was for somebody to examine me… and it leads to a lot of frustration for me and a lot of anxiety and it’s also hard to diagnose the problem. (#15, y/o Ukrainian female, lives alone in a house) |

| Health services | I have had access to my family doctor. I have had a phone call with him, then I have also had a phone call with a specialist because my family doctor has sent me to a specialist. It did go well but I don’t think it was sufficient. If I was sitting in his office, I’m pretty sure he would have asked me a few more questions. (#18, 78 y/o Black female, lives alone in a house) |

| Health services | I had great support from the palliative care team [that supported husband] and I must say, I’m okay, the support was good. I’m lucky that I’m quite healthy, so I didn’t have to go to too many appointments. And you know, most of my appointments are for my eye, and so one is cancelled because they were not very important, or delayed. So I was lucky to be in good health, so it didn’t affect me much that way. (#2, 74 y/o Caucasian female, widow lives alone in a condo) |

| Health services | I’ve had a Zoom doctor appointment and I’m concerned a little bit about how they’ve managed anything if they physically needed to see me. I think we’ve had some diminishment in medical attention, obviously they’ve been focusing on people who are much sicker. (#13, 73 y/o Jewish male, lives with spouse in a condominium) |

| codes | Subtheme 7: Use of Technology: A New Necessity |

| Need for new learning | I’ve had to bunk up on my technology, I’ve had to learn how to do zoom, I’ve had to learn how to photograph a check and not go the bank… So, we’re adapting to more of an online presence in our life, for everything—banking, talking to people, zooms. I’m more terrified of going out in public than I am of technology. (#22, 65 y/o Caucasian female, lives with spouse in a house) |

| Need for new learning | It was a learning experience. I don’t really one hundred percent like it as much. Like playing bridge online, or doing book club online, you know what I mean, it’s not as nice as being in a group setting that you have each other, you know. It’s okay… but I wouldn’t like it to have it all the time like that. I don’t want it to stay forever that way. In the meantime, I adjust. (#2, 74 y/o Caucasian female, widow lives alone in a condominium) |

| Need for new learning | FaceTime was a great support, again being my age and not being used to the social media and how to navigate that was a process as well, but those supports were there and definitely, definitely helpful. (#6, 71 y/o Caucasian female, lives alone in a house) |

| Need for assistance | Getting the internet set up was a little, but no, not too much stressful. Like, I had to call the company, like Rogers, several times and get them to help and come and set it up. And my nephew had to come and aid and get everything going with me. A little bit inconvenient but not stressful. (#18, 78 y/o Black female, lives alone in house) |

| Need for assistance | Some older adults don’t have the means to really communicate. For example, they don’t have computer skills, Zooming, and so on... Some need help, encourage them to be more active… help them find the means of communicating with others. There was one person but then she was adamant she didn’t want to use the Zoom. She thought it’s so complicated and she didn’t have a camera, she didn’t have a microphone. I really tried to push her and finally she is now happy that she is doing it, so there are people to help… These people don’t have the skill and some of them really not forthcoming they are not… because they think they are too old to learn these new techniques. (#17, 77 y/o Middle Eastern male, lives with spouse in a condominium) |

| Resistance | I have a very close friend and she is nagging me like crazy to do Zoom because she loves Zoom. I’m willing to try it just so that we can connect, but also because everything seems to be on Zoom. I should learn how to use it now, but I also should learn how to use it for what’s coming up because everything seems to be on Zoom. (#15, 65 y/o Ukrainian female, lives alone in a house) |

| Resistance | I’m not loving zoom, but it’s become kind of necessary I guess in all of this. (#3, 67 y/o Caucasian female, lives alone in a house) |

| Better than nothing | It was a learning experience. I don’t really one hundred percent like it as much. Like playing bridge online, or doing book club online, you know what I mean, it’s not as nice as being in a group setting that you have each other, you know. It’s okay… but I wouldn’t like it to have it all the time like that. I don’t want it to stay forever that way… In the meantime, I adjust. (#2, 74 y/o Caucasian female, widow lives alone in a condominium) |

| Better than nothing | I don’t get the same sense of encouragement on Zoom that I would on a face-to-face event. I mean it’s better than nothing but I’m not a big fan of this new technology, I’d rather have an actual dialogue with people. (#8, 71 y/o Caucasian female, lives with sister in co-op) |

| Unexpected benefits | It’s actually better in some ways because in book club, you get all these, it’s hard to hold focus “let’s talk about the book”. You got these two over here talking and those two over there talking and you’re like “excuse me, excuse me”. So, it’s actually easier when you’re all on a screen. (#22, 65 y/o Caucasian female, lives with spouse in house) |

| Unexpected benefits | The thing is we can’t see them [i.e., mom in nursing home]. We could see them through the window, which is fine. But now you can’t see them at all. So, this is what we do three times a week, I’m on Facebook with my mom, so thank God for that. (#4, 69 y/o Caucasian female, lives with spouse in a house) |

| Unexpected benefits | I mean to be honest, it’s kind of nice that all these speakers are coming to me, and I don’t have to drive all over the place, or get on the TTC to hear this speaker, or that speaker. (#20, 67 y/o Caucasian female, living with spouse in a condominium) |

| Unexpected benefits | We both have our own laptop, so we can reading, listening, musical arts performance is more than before. Free, hahahah! Specially opera, which I am really fanatic about, and he likes the sports, so we have own time to do that without much boredom or anything. (#19, 78 y/o Korean female, lives with spouse in a condominium) |

| Theme 2: Coping with the COVID-19 Pandemic | |

| codes | Subtheme 1: Behavioral strategies |

| Mask wearing and other precautions | Because I’m asthmatic, I was wearing the disposable masks, I really had trouble breathing. But I was determined to find a mask I could wear, and since then, we’ve found cloth masks that don’t bother my breathing so much. I tried to find something that would work instead of just saying ‘well I can’t wear a mask,’ because I feel very vulnerable with my autoimmune disease. I’m glad that I found that because I feel protected and I’m protecting other people from me too. (#8, 71 y/o Caucasian female, lives with family in group housing) |

| Mask wearing and other precautions | I believe the physical social distancing, cleaning hand, to clean more surface…I’m a chemistry major, so I really believe those directions. Very naïve way, but [that is] only [what] they can suggest now without the vaccine development. So, I trust all the direction. If I follow, I am more safe. (#19, 78 y/o Korean female, lives with spouse in a condominium) |

| Minimizing media | I was listening to that [CBC news] all the time, all the shows, you know. I would have it on all day. So that I’ve eliminated, and I think that I’m less anxious because of that. (#10, 72 y/o Celtic Jewish female, lives with family in group housing) |

| Minimizing media | I don’t watch the news now. I catch the headlines of an article on my iPad. I keep up on it enough that way, for me. I don’t need the details every single day. It’s too disturbing. (#20, 67 y/o Caucasian female, living with spouse in a condominium) |

| Minimizing media | It’s loaded. It’s too much. It’s overload. Too much news, too much information sometimes. That’s why I shut it off… (#2, 74 y/o Caucasian female widow, lives alone in a condominium) |

| Making a schedule | I try to make sure I have a schedule. I get up, I do a fitness routine, I get dressed, I have a zoom something in the morning or, you know I really try hard to make sure that I do have the structure. And I also make sure that I get out every day because I think, first, the fresh air…so I see lots of green, which is very important for me. (#21, 75 y/o Jewish female widow, lives alone in a condominium) |

| Making a schedule | Each day I would have a goal for myself and usually when I do that I’m home, I get up, let’s do this but let’s get out, but I found that I really had to force myself some days to do things that that were on my list, so I did them but I didn’t do them with a great deal of enthusiasm. (#6, 71 y/o Caucasian female, lives alone in a house) |

| Pivoting | It didn’t really impact my wellbeing at all, it was just a shift in what to do with my available free time. Instead of sitting around and moping, you know, I walked more, biked more, made it home more, watched the news. It’s just a shift in how one occupies oneself, productively, stimulating. (#16, 70 y/o Jewish male, lives with common-law partner in a condominium) |

| Pivoting | One activity I’m doing that I wasn’t doing before, I started to learn to bake. I’ve started with scones, which I never did before, and we’ve been watching the great Canadian and Great British baking show, and that kind of inspired me to, you know, sort of challenge for me, so in a positive way that’s affected that. (#10, 72 y/o Celtic Jewish female, lives with family in group housing) |

| Pivoting | One positive aspect is that I sort of did activities that I wanted to do before but didn’t have the time, like trying to improve my language and my voice. (#17, 77 y/o Middle Eastern male, lives with spouse in a condominium) |

| Keeping busy | I have more time for myself now—to do whatever I want to do. I have more things to do now. (#1, 75 y/o Filipino male, living with spouse and children in a house) |

| Keeping busy | All kinds of things are popping up in my head that now are filling time for me. I think the more you open your mind to what you could be doing, the pandemic takes a little back seat for that while. Gardening, I think, takes my mind off a lot of other things, cuts about the weed. I think that’s all healthy stuff…I think our busyness helps. (#5, 74 y/o Caucasian female, lives with spouse in a house) |

| Not Pivoting (Importance of being self-directed) | Well because it’s like you have no purpose, like you can’t go do the things you normally would do, you know, like you know, on a Monday I did this, I went here and I… all that stuff I can’t do. I can’t socialize with a group of friends and go play cards or do whatever because we can’t do it right now, you know, so anything you planned or look forward to, you really can’t do, you know. (#4, 69 y/o Caucasian female, lives with spouse in a house) |

| Physical activity | I still try to do things that I was doing before the pandemic, you know. Even though I might go for a walk and I know my knees are gonna be ached, I’ll still go out. (#11, 74 y/o Jewish male, living with spouse in a condominium) |

| Being outdoors/Physical activity | We do most of our walking in the morning, if it’s a nice day and by that I mean 24–25 degrees, we’ll walk in the afternoon sometimes, and I’ll be honest our deck overlooks a walking path and we see a lot of seniors walking. They walk and they walk and it’s a way to break up the monotony of being indoors. (#9, 73 y/o Caucasian male, lives with spouse in a house). |

| Being outdoors | The garden has been a tremendous comfort to counteract all that other negative stuff. (#7, 81 y/o Caucasian male, lives with same-sex spouse in an apartment) |

| codes | Subtheme 2: Emotion-focused strategies |

| Hope and Optimism | You have to kind of believe that it’s going to be OK because I think if you’re a negative person and you just go to bed at night and go you know it’s all for naught. Well, that’s tough. I think that’s a hard way to live, and I think that’s going to make people ill. (#5, 74 y/o Caucasian female lives with spouse in a house) |

| Hope and Optimism | I make the best of whatever I can do, always have. I’ve always, shall we say, risen to the occasion, no matter what it is, whether it’s some kind of an emergency or whether it’s this. (#14, 70 y/o Irish Jewish female, lives with spouse in a condominium) |

| Hope and Optimism | It’s just part of my personality, I don’t give into fear. You know, even in earlier times in my life when I had back issues, for example, and you know like I was bedridden for a while, but I just wouldn’t give into it, you know. I just felt like, ‘OK, well let’s figure out a way to recover from this and get on with life’, right. I just don’t give into that kind of thing or if I’ve had you know bad things happen, I won’t live my life in fear. (#3, 67 y/o Caucasian female, lives alone in a house) |

| Gratitude and small pleasures | I think the more you open your mind to what you could be doing, the pandemic takes a little back seat for that while… We’re both ice cream people, so we just go get an ice cream and sit in the car and eat it and come home, you know. I think you have to pick your pleasures. They’re little, but they’re not as little as they used to be. Now getting an ice cream cone is a big deal. (#5, 74 y/o Caucasian female, lives with spouse in a house) |

| Gratitude and small pleasures | I’m just so grateful that I did have a home over my head, I had lots of food, financially I wasn’t stressed, so I’m very happy about that. (#6, 71 y/o Caucasian female, lives alone in a house) |

| Acceptance | I’m not apprehensive so much as accepting that it [subsequent wave] will happen and to just work my way through it when it does. (#14, 70 y/o Irish Jewish female, lives with spouse in a condominium) |

| Acceptance | If I die, I die. I mean at this age it’s kind of moot as to whether or not and it’s gonna happen and I’m sort of resigned to that fact. I’ve had cancer, I’m now not getting enough exercise which I think every day lessens my chance of a longer life, but it’s all sort of, you know, benign acceptance rather than intense worrying. I’ve had a wonderful life and I don’t really mind that I’m closer to death than most people are. (#7, 81 y/o Caucasian male, living with same-sex spouse in an apartment) |

| Perspective taking | I tend to be a very positive person and because I’m also used to living alone, it’s not as big a change for me… I’ve had enough tragedies in my life that you see, different people adapt to things differently. Sometimes when you’re faced with a difficult situation you grow; other times you just fall apart. Because I’ve been through a lot of things I try to reach out to people who might need a helping hand because, again I really am very lucky. I have wonderful family and friends, and it really makes a big difference. (#21, 75 y/o Jewish female, widow lives alone in a condominium) |

| Perspective taking | Transplant patients have learned to look after themselves... and so I don’t know! I guess I’m so grateful to be alive that I’m going to enjoy every minute of it. The gratitude that I have today is much greater than I ever had before…possibly the experience that I’ve gone through, I’ve had a second chance at life, like I should be dead, right?…and so you have a choice, you can either bounce off the walls or you can enjoy what you got! Yeah we’re living through a tough time right now, you have a choice to enjoy it or not, I choose to enjoy it. (#9, 73 y/o Caucasian male, lives with spouse in a house) |

| Perspective taking | Our grandparents were refugees, and their parents had to deal with the pilgrims, and they had to come here with a suitcase. Also, in the Irish side, our grandfather came here and his father died. I think our family has ingrained in our DNA ‘just get on with it, and do what you have to do to keep on going,’ and I think that really helps in the pandemic time. (#10, 72 y/o Celtic Jewish female, lives with family in group housing) |

| Perspective taking | We came here at a vibrant age. Immigrant here. So we face difficulty in mid-20s. So maybe not like pandemic COVID-19 hardship, we had already hardship without the language, plus some level of racism and then during that time I was pregnant. (#19, 78 y/o Korean female, lives with spouse in a condominium) |

| Perspective taking | We haven’t had all the negatives that other people have experienced, we don’t have little kids to worry about we don’t have to homeschool, we don’t have to worry about if we’re going to keep our jobs. My age is such that I don’t have the physical infirmities that will cascade upon me when I hit 85 or 90. I’m in that lovely part of the seniors spectrum where I’ve got all the advantages and none of the disadvantages. (#12, 70 y/o Caucasian male, living with spouse in a house) |

| Meaning-making | There is a COVID-19 pandemic versus a racism pandemic. But this COVID-19 pandemic gave me more voices about the decision… I have more facts to [relay] to other people in my community who are kind of ignorant with subtle racism underneath. So, we need more education about it. Its all relatable. Its nothing separate issues. (#19, 78 y/o Korean female, lives with spouse in a condominium) |

| Silver lining | It’s given me a different perspective on things, on what things are truly important. Small things that you take for granted that are important to your well being, a different perspective on that, I’m so grateful for those things. (#6, 71 y/o Caucasian female, lives alone in a house) |

| Silver lining | People have stepped up to the plate to try to adjust to new circumstances and they’ve done remarkably well in my opinion…this challenge [the pandemic] has really made us see what wonderful people that we have in our community. (#13, 73 y/o Jewish male, lives with spouse in a condominium) |

| codes | Subtheme 3: Social Support |

| Being connected | So, part of the ease of going through the pandemic is the way we’re all connected. Fifty years ago, how would you have done? (#12, 70 y/o Caucasian male, lives with spouse in a house) |

| Being connected | It’s just maybe three women sharing three different feelings, and most of those conversations end up in all three or all four of us being a whole lot better because, you know, you’re not the only one feeling it. You know, you’re not the only one that doesn’t have the answers, and that gets scared sometimes. But I find my outlet with my friends always makes me stronger and I think we all we all hang up and go, ‘Yeah I can do this. I feel better’. (#5, 74 y/o Caucasian female, lives with spouse in house) |

| Supported by spouse | He’s definitely the one that will talk me down from something. So, if I say, you know, “What if?” He’ll just say, “Don’t what if it.” Just, you know, we’ll cross that bridge. He’s a lot more sensible and not up and down like I am. (#5, 74 y/o Caucasian female, lives with spouse in house) |

| Need for more support | I am always wishing for more support and I, so that’s you know, that’s an ongoing theme for me…my hopes and my wishes for you know social interaction and for people, you know coming to take care of me is unrealistic, and it was unrealistic before the pandemic. It’s great that my brother would come every Saturday but I also wanted him to phone me twice a week. Or even my friend in [city], I would hope that she would call me more than once a week … I think people have their own lives, I don’t think that’s completely realistic but that’s what I would want. (#15, 65 y/o Ukrainian female, lives alone in a house) |

| Supporting others | Father Vincent [pseudonym] sends me little jobs… my capabilities on the Internet are limited and he knows that so he’ll give me a list of calls to parishioners and just say ‘I’m calling on behalf of Father Vincent who just wanted to know how are you doing? Do you need anything?’ You know, so that’s a blessing. ‘Cause if you call 5 people in a day and you help one person who’s alone and say to them, ‘Listen, I’m calling on behalf of the perish, but you can have my phone number, and if you just wanted to chat you know I’m home, I’m stuck here too’. I’ve had a few calls, and I have to tell you, if you ever think that that’s not a blessing, you’re crazy, because that will take your mind off anything that you’re feeling. A couple of times, I talked to a senior, and I don’t know if I made them feel better, but I felt better. It was like I was talking to me. (#5, 74 y/o Caucasian female, lives with spouse in a house) |

| Supporting others | I would just take a little chair, sit outside her window when they open up the top so we could hear each other talk you know, stuff like that. … like not being able to go in and explain to her, that’s been my biggest… breaks my heart! because she doesn’t understand…and then she’ll say like there’s nobody here, nobody comes, and stuff like that, ‘cause they’re all confined to their rooms so they don’t leave the room at all… and she hasn’t left it in three or four months so that’s hard. (#4, 69 y/o Caucasian female, lives with spouse in a house) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fiocco, A.J.; Gryspeerdt, C.; Franco, G. Stress and Adjustment during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study on the Lived Experience of Canadian Older Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12922. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182412922

Fiocco AJ, Gryspeerdt C, Franco G. Stress and Adjustment during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study on the Lived Experience of Canadian Older Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(24):12922. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182412922

Chicago/Turabian StyleFiocco, Alexandra J., Charlie Gryspeerdt, and Giselle Franco. 2021. "Stress and Adjustment during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study on the Lived Experience of Canadian Older Adults" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 24: 12922. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182412922

APA StyleFiocco, A. J., Gryspeerdt, C., & Franco, G. (2021). Stress and Adjustment during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study on the Lived Experience of Canadian Older Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(24), 12922. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182412922