Motives for Crafting Work and Leisure: Focus on Opportunities at Work and Psychological Needs as Drivers of Crafting Efforts

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Crafting One’s Job in Accordance with Psychological Needs: Needs as Crafting Drivers

2.2. Focus on Opportunities at Work as a Motivational Antecedent of Crafting

2.3. Psychological Needs as Mediators between Focus on Opportunities at Work and Crafting Efforts

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.3. Control Variables

3.4. Statistical Analyses

3.5. Hypotheses Testing

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

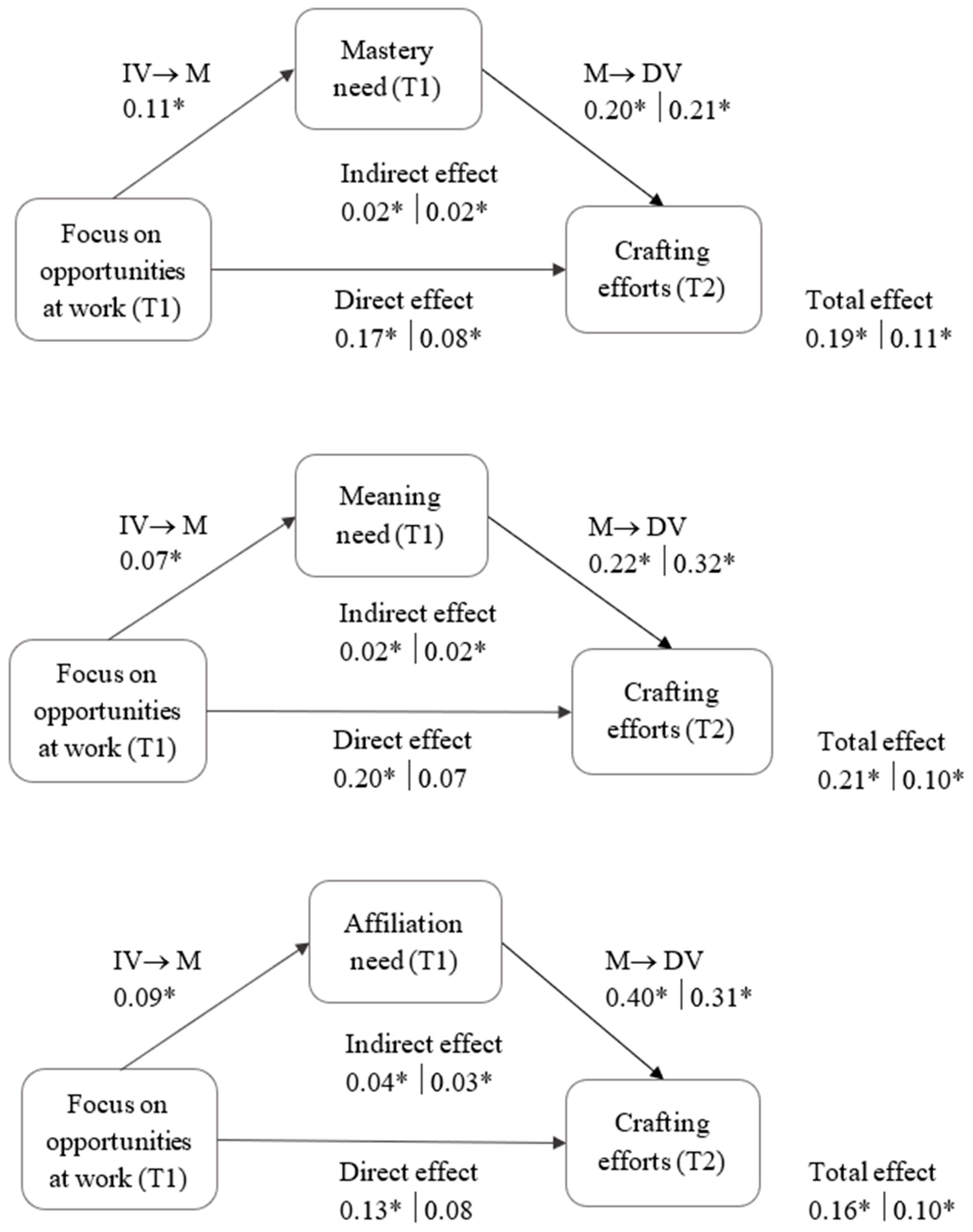

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Crafting and the COVID-19 Pandemic

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bliese, P.D.; Edwards, J.R.; Sonnentag, S. Stress and well-being at work: A century of empirical trends reflecting theoretical and societal influences. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheatley, D.; Hardill, I.; Buglass, S. Handbook of Research on Remote Work and Worker Well-Being in the Post-COVID-19 Era; Wheatley, D., Hardill, I., Buglass, S., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, C.W.; Lavigne, K.N.; Katz, I.M.; Zacher, H. Linking dimensions of career adaptability to adaptation results: A meta-analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 102, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongratz, H.J.; Voß, G.G. From employee to ‘entreployee’: Towards a ‘self-entrepreneurial’ work force? Concepts Transform. 2003, 8, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frese, M.; Fay, D. Personal initiative: An active performance concept for work in the 21st century. Res. Organ. Behav. 2001, 23, 133–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Ashford, S.J. The dynamics of proactivity at work. Res. Organ. Behav. 2008, 28, 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubicek, B.; Tement, S. Work intensification and the work-home interface: The moderating effect of individual work-home segmentation strategies and organizational segmentation supplies. J. Pers. Psychol. 2016, 15, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, G.N.; Greenhaus, J.H.; Allen, T.D.; Johnson, R.E. Advancing and expanding work-life theory from multiple perspectives. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2019, 44, 54–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B. Job crafting: Towards a new model of individual job redesign. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2010, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; Dutton, J.E. Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Tims, M.; Derks, D. Proactive personality and job performance: The role of job crafting and work engagement. Hum. Relat. 2012, 65, 1359–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. Job crafting and job performance: A longitudinal study. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2015, 24, 914–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bloom, J.; Vaziri, H.; Tay, L.; Kujanpää, M. An identity-based integrative needs model of crafting: Crafting within and across life domains. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 1423–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “ What “ and “ Why “ of goal pursuits: Human needs and the delf-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Rothbard, N.P. Mechanisms linking work and family: Clarifying the relationship between work and family constructs. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 178–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rudolph, C.W.; Katz, I.M.; Lavigne, K.N.; Zacher, H. Job crafting: A meta-analysis of relationships with individual differences, job characteristics, and work outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 102, 112–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacher, H.; Frese, M. Remaining time and opportunities at work: Relationships between age, work characteristics, and occupational future time perspective. Psychol. Aging 2009, 24, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L.L. Evidence for a Life-Span Theory of Socioemotional Selectivity. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1995, 4, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, F.R.; Carstensen, L.L. Time counts: Future time perspective, goals, and social relationships. Psychol. Aging 2002, 17, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, S.K.; Bindl, U.K.; Strauss, K. Making things happen: A model of proactive motivation. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 827–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sheldon, K.M.; Gunz, A. Psychological needs as basic motives, not just experiential requirements. J. Pers. 2009, 77, 1467–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, D.B.; Tay, L.; Diener, E. Leisure and subjective well-being: A model of psychological mechanisms as mediating factors. J. Happiness Stud. 2014, 15, 555–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, K.M.; Elliot, A.J. Goal striving, need satisfaction, and longitudinal well-being: The self-concordance model. J. Pers. 1999, 76, 482–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, J.M.; Dutton, J.E.; Wrzesniewski, A. Job crafting and meaningful work. In Purpose and Meaning in the Workplace; Dik, D.J., Byrne, Z.S., Steger, M.S., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; pp. 81–104. [Google Scholar]

- Kooij, D.T.A.M.; Tims, M.; Akkermans, J. The influence of future time perspective on work engagement and job performance: The role of job crafting. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2017, 26, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kooij, D.T.A.M.; Nijssen, H.; Bal, P.M.; van der Kruijssen, D.T.F. Crafting an Interesting Job: Stimulating an Active Role of Older Workers in Enhancing Their Daily Work Engagement and Job Performance. Work. Aging Retire 2020, 6, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuijpers, E.; Kooij, D.T.A.M.; van Woerkom, M. Align your job with yourself: The relationship between a job crafting intervention and work engagement, and the role of workload. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bindl, U.K.; Unsworth, K.L.; Gibson, C.B.; Stride, C.B. Job crafting revisited: Implications of an extended framework for active changes at work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2019, 104, 605–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Elliot, A.J. The hierarchical model of approach-avoidance motivation. Motiv. Emot. 2006, 30, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Parker, S.K. Reorienting job crafting research: A hierarchical structure of job crafting concepts and integrative review. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 126–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujanpää, M.; Syrek, C.; Lehr, D.; Kinnunen, U.; Reins, J.A.; de Bloom, J. Need Satisfaction and optimal functioning at leisure and work: A longitudinal validation study of the DRAMMA model. J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 22, 681–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sonnentag, S.; Fritz, C. The Recovery Experience Questionnaire: Development and validation of a measure for assessing recuperation and unwinding from work. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 204–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bennett, A.A.; Bakker, A.B.; Field, J.G. Recovery from work-related effort: A meta-analysis. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Brummelhuis, L.L.; Trougakos, J.P. The recovery potential of intrinsically versus extrinsically motivated off-job activities. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2014, 87, 177–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, Y. Pathways to meaning-making through leisure-like pursuits in global contexts. J. Leis. Res. 2008, 40, 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Beyers, W.; Boone, L.; Deci, E.L.; Van der Kaap-Deeder, J.; Duriez, B.; Lens, W.; Matos, L.; Mouratidis, A.; et al. Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motiv. Emot. 2015, 39, 216–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, K.M.; Schüler, J. Wanting, having, and needing: Integrating motive disposition theory and self-determination theory. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 101, 1106–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berg, J.M.; Grant, A.M.; Johnson, V. When callings are calling: Crafting work and leisure in pursuit of unanswered occupational callings. Organ. Sci. 2010, 21, 973–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Petrou, P.; Bakker, A.B. Crafting one’s leisure time in response to high job strain. Hum. Relat. 2016, 69, 507–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Demerouti, E.; Hewett, R.; Haun, V.; De Gieter, S.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, A.; Skakon, J. From job crafting to home crafting: A daily diary study among six European countries. Hum. Relat. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hirschi, A.; Steiner, R.; Burmeister, A.; Johnston, C.S. A whole-life perspective of sustainable careers: The nature and consequences of nonwork orientations. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 117, 103319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.M.; Strauss, K.; Arnold, J.; Stride, C. The relationship between leisure activities and psychological resources that support a sustainable career: The role of leisure seriousness and work-leisure similarity. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 117, 103340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuykendall, L.; Tay, L.; Ng, V. Leisure engagement and subjective well-being: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 364–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuykendall, L.; Lei, X.; Tay, L.; Cheung, H.K.; Kolze, M.J.; Lindsey, A.; Silvers, M.; Engelsted, L. Subjective quality of leisure & worker well-being: Validating measures & testing theory. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 103, 14–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujanpää, M.; Weigelt, O.; Shimazu, A.; Toyama, H.; Kosenkranius, M.; Kerksieck, P.; de Bloom, J. The Forgotten Ones: Crafting for Meaning and for Affiliation in the Context of Finnish and Japanese Employees ’ Off-Job Lives. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosenkranius, M.K.; Rink, F.A.; De Bloom, J.; Van Den Heuvel, M. The design and development of a hybrid off-job crafting intervention to enhance needs satisfaction, well-being and performance: A study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2002, 6, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; She, Z.; Li, D.; Zhang, H.; Niu, K. Job crafting promotes internal recovery state, especially in jobs that demand self-control: A daily diary design. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L.L.; Isaacowitz, D.M.; Charles, S.T. Taking time seriously. A theory of socioemotional selectivity. Am. Psychol. 1999, 54, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cate, R.A.; John, O.P. Testing models of the structure and development of future time perspective: Maintaining a focus on opportunities in middle age. Psychol. Aging 2007, 22, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weikamp, J.G.; Göritz, A.S. How stable is occupational future time perspective over time? A six-wave study across 4 years. Work. Aging Retire 2015, 1, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froehlich, D.E.; Beausaert, S.; Segers, M. Aging and the motivation to stay employable. J. Manag. Psychol. 2016, 31, 756–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lange, A.H.; Pak, K.; Osagie, E.; Van Dam, K.; Christensen, M.; Furunes, T.; Tevik Løvseth, L.; Detaille, S. An open time perspective and social support to sustain in healthcare work: Results of a two-wave complete panel study. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudolph, C.W.; Kooij, D.T.A.M.; Rauvola, R.S.; Zacher, H. Occupational future time perspective: A meta-analysis of antecedents and outcomes. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kooij, D.T.A.M.; Bal, P.M.; Kanfer, R. Future time perspective and promotion focus as determinants of intraindividual change in work motivation. Psychol. Aging 2014, 29, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kooij, D.; van de Voorde, K. How changes in subjective general health predict future time perspective, and development and generativity motives over the lifespan. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2011, 84, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, P.; Pentti, J.; Vahtera, J.; Kivimäki, M.; Virtanen, M. Self-Rated Health of the Temporary Employees in a Nordic Welfare State: Findings from the Finnish Public Sector Study. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 60, e106–e111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Eurofound. Sixth European Working Conditions Survey—Overview Report (2017 Update); Eurofound: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound. Living, Working and COVID-19; 59; Eurofound: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zacher, H.; Frese, M. Maintaining a focus on opportunities at work: The interplay between age, job complexity, and the use of selection, optimization, and compensation strategies. J. Organ. Behav. 2011, 32, 291–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Bloom, J.; Syrek, C.; Lamers, E.; Burkardt, S. But the memories last forever. Vacation reminiscence and recovery from job stress: A psychological needs perspective. Wirtsch. Aktuell 2017, 19, 64–78. [Google Scholar]

- Claes, R.; Beheydt, C.; Lemmens, B. Unidimensionality of abbreviated Proactive Personality Scales across cultures. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 54, 476–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, A.M. Insufficient discriminant validity: A comment on Bove, Pervan, Beatty, and Shiu (2009). J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 324–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, J.L. Amos (Version 25.0) [Computer Program]; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2017; Available online: https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/downloading-ibm-spss-amos-25 (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Müller, H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods Psychol. Res. 2003, 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2017; Available online: https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/downloading-ibm-spss-statistics-25 (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Hayes, A.F., Little, T.D., Eds.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Inst. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smit, B.W. Successfully leaving work at work: The self-regulatory underpinnings of psychological detachment. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2016, 89, 493–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, T.S.; Crant, J.M. The proactive component of organizational behavior: A measure and correlates. J. Organ. Behav. 1993, 14, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, K.; Parker, S.K. Effective and sustained proactivity in the workplace: A self-determination theory perspective. In The Oxford Handbook of Work Engagement, Motivation, and Self-Determination Theory; Gagné, M., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 50–71. ISBN 9780199794911. [Google Scholar]

- Westman, M.; Hobfoll, S.E.; Chen, S.; Davidson, O.B.; Laski, S. Organizational stress through the lens of Conservation of Resources (COR) theory. Res. Occup. Stress Well Being 2004, 4, 167–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 50, 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slemp, G.R.; Vella-Brodrick, D.A. Optimising employee mental health: The relationship between intrinsic need satisfaction, job crafting, and employee well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 2014, 15, 957–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, A.; Van der Heijden, B.I.J.M.; Akkermans, J. Sustainable careers: Towards a conceptual model. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 117, 103196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gellert, P.; Ziegelmann, J.P.; Lippke, S.; Schwarzer, R. Future time perspective and health behaviors: Temporal framing of self-regulatory processes in physical exercise and dietary behaviors. Ann. Behav. Med. 2012, 43, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochoian, N.; Raemdonck, I.; Frenay, M.; Zacher, H. The role of age and occupational future time perspective in workers’ motivation to learn. Vocat. Learn. 2017, 10, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, E.M.; Ziegler, N.; Schippers, M.C. From shattered goals to meaning in life: Life crafting in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 577708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caringal-Go, J.F.; Teng-Calleja, M.; Bertulfo, D.J.; Manaois, J.O. Work-life balance crafting during COVID-19: Exploring strategies of telecommuting employees in the Philippines. Commun. Work Fam. 2021, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Hadi, S.; Bakker, A.B.; Häusser, J.A. The role of leisure crafting for emotional exhaustion in telework during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anxiety Stress Coping 2021, 34, 530–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, T.; Cao, L.; Chin, T. Crafting jobs for occupational satisfaction and innovation among manufacturing workers facing the COVID-19 crisis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health 2020, 17, 3953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Dollard, M.F.; Taris, T.W. Organizational context matters: Psychosocial safety climate as a precursor to team and individual motivational functioning. Saf. Sci. 2022, 145, 105524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W.; Shimazu, A.; Dollard, M.F. Resource crafting: Is it really “resource” crafting-or just crafting? Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mäkikangas, A.; Aunola, K.; Seppälä, P.; Hakanen, J. Work engagement–team performance relationship: Shared job crafting as a moderator. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2016, 89, 772–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachler, V.; Epple, S.D.; Clauss, E.; Hoppe, A.; Slemp, G.R.; Ziegler, M. Measuring job crafting across cultures: Lessons learned from comparing a German and an Australian sample. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yepes-Baldó, M.; Romeo, M.; Westerberg, K.; Nordin, M. Job crafting, employee well-being, and quality of care. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2018, 40, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gordon, H.J.; Demerouti, E.; Le Blanc, P.M.; Bipp, T. Job crafting and performance of Dutch and American health care professionals. J. Pers. Psychol. 2015, 14, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age (T1) | 48.8 | 10.0 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Proactive personality (T1) | 3.7 | 0.7 | −0.03 | (0.81) | |||||||||||||||||||

| 3. FoO at work (T1) | 2.9 | 1.2 | −0.35 ** | 0.29 ** | (0.94) | ||||||||||||||||||

| 4. Detachment need (T1) | 4.3 | 0.9 | −0.05 | 0.00 | −0.07 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 5. Relaxation need (T1) | 3.9 | 0.9 | −0.02 | −0.06 | −0.04 | 0.49 ** | |||||||||||||||||

| 6. Autonomy need (T1) | 4.4 | 0.6 | −0.04 | 0.26 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.32 ** | (0.67) | |||||||||||||||

| 7. Mastery need (T1) | 4.3 | 0.6 | −0.13 * | 0.30 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.13 * | 0.19 ** | 0.46 ** | (0.66) | ||||||||||||||

| 8. Meaning need (T1) | 4.5 | 0.5 | −0.03 | 0.17 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.59 ** | (0.71) | |||||||||||||

| 9. Affiliation need (T1) | 4.2 | 0.8 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.14 * | 0.15 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.44 ** | (0.88) | ||||||||||||

| 10. OJC for detachment (T2) | 3.6 | 1.0 | 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.29 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.11 * | 0.11 * | 0.13 * | 0.06 | (0.91) | |||||||||||

| 11. OJC for relaxation (T2) | 3.5 | 0.8 | 0.18 ** | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.17 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.14 ** | 0.13 * | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.59 ** | (0.84) | ||||||||||

| 12. OJC for autonomy (T2) | 3.8 | 0.8 | 0.23 ** | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.10 | 0.17 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.39 ** | 0.58 ** | (0.86) | |||||||||

| 13. OJC for mastery (T2) | 3.3 | 0.7 | 0.15 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.20 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.16 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.42 ** | 0.46 ** | (0.67) | ||||||||

| 14. OJC for meaning (T2) | 3.7 | 0.8 | 0.14 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.11 * | 0.06 | 0.13 * | 0.26 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.49 ** | 0.54 ** | 0.65 ** | (0.89) | |||||||

| 15. OJC for affiliation (T2) | 3.8 | 0.8 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.12 * | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.13 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.31 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.55 ** | (0.87) | ||||||

| 16. JC for detachment (T2) | 3.7 | 0.9 | 0.06 | −0.03 | −0.02 | 0.25 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.15 ** | 0.63 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.42 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.36 ** | (0.91) | |||||

| 17. JC for relaxation (T2) | 3.6 | 1.0 | 0.14 ** | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.15 ** | 0.14 * | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.14 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.61 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.43 ** | 0.46 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.79 ** | (0.92) | ||||

| 18. JC for autonomy (T2) | 3.4 | 0.9 | 0.10 | 0.24 ** | 0.25 ** | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.19 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.29 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.37 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.54 ** | (0.84) | |||

| 19. JC for mastery (T2) | 3.7 | 0.7 | 0.05 | 0.24 ** | 0.30 ** | −0.03 | 0.00 | 0.19 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.37 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.58 ** | (0.76) | ||

| 20. JC for meaning (T2) | 3.7 | 0.8 | 0.08 | 0.21 ** | 0.27 ** | −0.06 | 0.02 | 0.15 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.43 ** | 0.47 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.33 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.58 ** | 0.69 ** | (0.86) | |

| 21. JC for affiliation (T2) | 3.4 | 0.9 | 0.15 ** | 0.13 * | 0.16 ** | 0.05 | 0.12 * | 0.14 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.33 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.42 ** | 0.31 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.37 ** | 0.47 ** | 0.61 ** | (0.89) |

| Model | χ2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Six-factor JC model | 319.57 | 115 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

| Two-factor JC model | 428.01 | 127 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.08 | 0.07 |

| One-factor JC model | 600.91 | 117 | 0.90 | 0.87 | 0.11 | 0.10 |

| Six-factor OJC model | 209.43 | 115 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Two-factor OJC model | 358.41 | 123 | 0.89 | 0.94 | 0.08 | 0.10 |

| One-factor OJC model | 358.89 | 122 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.08 | 0.07 |

| DRAMMA Dimension | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detachment | Relaxation | Autonomy | Mastery | Meaning | Affiliation | |

| X → M | b = −0.08, SE = 0.05, 95% CI [−0.18, 0.01] | b = −0.03, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [−0.12, 0.06] | b = 0.04, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [−0.02, 0.09] | b = 0.11, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [0.05, 0.16] | b = 0.07, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [0.02, 0.13] | b = 0.09, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [0.01, 0.17] |

| Job crafting | ||||||

| M → Y | b = 0.26, SE = 0.05, 95% CI [0.16, 0.37] | b = 0.18, SE = 0.06, 95% CI [0.06, 0.29] | b = 0.20, SE = 0.08, 95% CI [0.04, 0.36] | b = 0.20, SE = 0.06, 95% CI [0.07, 0.32] | b = 0.22, SE = 0.08, 95% CI [0.07, 0.38] | b = 0.40, SE = 0.06, 95% CI [0.29, 0.51] |

| Total effect | b = 0.01, SE = 0.05, 95% CI [−0.09, 0.10] | b = 0.05, SE = 0.05, 95% CI [−0.05, 0.14] | b = 0.20, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [0.12, 0.29] | b = 0.19, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [0.12, 0.25] | b = 0.21, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [0.13, 0.29] | b = 0.16, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [0.08, 0.25] |

| Direct effect | b = 0.02, SE = 0.05, 95% CI [−0.07, 0.12] | b = 0.05, SE = 0.05, 95% CI [−0.06, 0.15] | b = 0.19, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [0.11, 0.28] | b = 0.17, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [0.10, 0.23] | b = 0.20, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [0.12, 0.27] | b = 0.13, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [0.04, 0.21] |

| Indirect effect | b = −0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [−0.05, 0.00] | b = −0.01, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [−0.03, 0.01] | b = 0.01, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [−0.00, 0.02] | b = 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.00, 0.04] | b = 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.00, 0.04] | b = 0.04, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [0.00, 0.07] |

| Off-job crafting | ||||||

| M → Y | b = 0.31, SE = 0.05, 95% CI [0.20, 0.41] | b = 0.19, SE = 0.05, 95% CI [0.10, 0.29] | b = 0.32, SE = 0.08, 95% CI [0.17, 0.47] | b = 0.21, SE = 0.06, 95% CI [0.09, 0.33] | b = 0.32, SE = 0.08, 95% CI [0.16, 0.47] | b = 0.31, SE =0.05, 95% CI [0.20, 0.42] |

| Total effect | b = −0.00, SE = 0.05, 95% CI [−0.10, 0.09] | b = 0.03, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [−0.06, 0.11] | b = 0.04, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [−0.04, 0.12] | b = 0.11, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [0.04, 0.17] | b = 0.10, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [0.02, 0.18] | b = 0.10, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [0.02, 0.19] |

| Direct effect | b = 0.02, SE = 0.05, 95% CI [−0.07, 0.12] | b = 0.03, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [−0.05, 0.11] | b = 0.03, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [−0.05, 0.11] | b = 0.08, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [0.02, 0.15] | b = 0.07, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [−0.01, 0.16] | b = 0.08, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [−0.00, 0.16] |

| Indirect effect | b = −0.03, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [−0.06, 0.00] | b = −0.01, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [−0.03, 0.01] | b = 0.01, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [−0.01, 0.03] | b = 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.01, 0.04] | b = 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.00, 0.05] | b = 0.03, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.00, 0.06] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kosenkranius, M.; Rink, F.; Kujanpää, M.; de Bloom, J. Motives for Crafting Work and Leisure: Focus on Opportunities at Work and Psychological Needs as Drivers of Crafting Efforts. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12294. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312294

Kosenkranius M, Rink F, Kujanpää M, de Bloom J. Motives for Crafting Work and Leisure: Focus on Opportunities at Work and Psychological Needs as Drivers of Crafting Efforts. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(23):12294. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312294

Chicago/Turabian StyleKosenkranius, Merly, Floor Rink, Miika Kujanpää, and Jessica de Bloom. 2021. "Motives for Crafting Work and Leisure: Focus on Opportunities at Work and Psychological Needs as Drivers of Crafting Efforts" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 23: 12294. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312294

APA StyleKosenkranius, M., Rink, F., Kujanpää, M., & de Bloom, J. (2021). Motives for Crafting Work and Leisure: Focus on Opportunities at Work and Psychological Needs as Drivers of Crafting Efforts. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23), 12294. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312294