A Systematic Review of Co-Educational Models in School Handball

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A description of the bibliography of studies published in relation to co-education and handball.

- The presentation of a mind-map of keywords representing the research work considered.

- An analysis of the purposes of the investigations was selected on the basis of a co-educational perspective of handball as a school sport.

- A summary of the principal results and conclusion of this analysis of publications relating to co-educational perceptions in school handball.

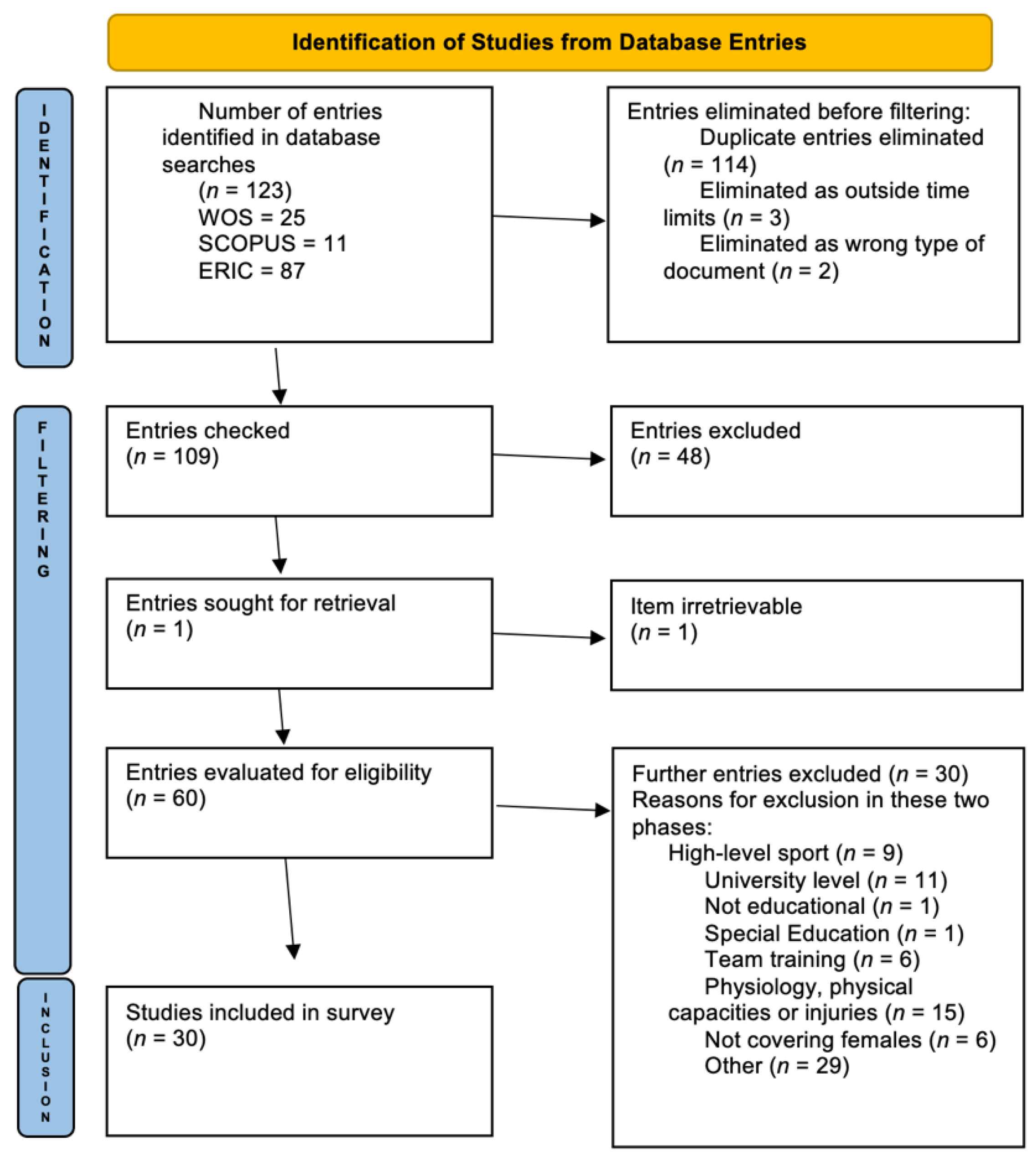

2. Methods

- Type of document: Academic articles and reviews

- Time limit: 2010 to 2021 (up to April of this last year)

- Language of publication: English, Spanish, or Portuguese

3. Results

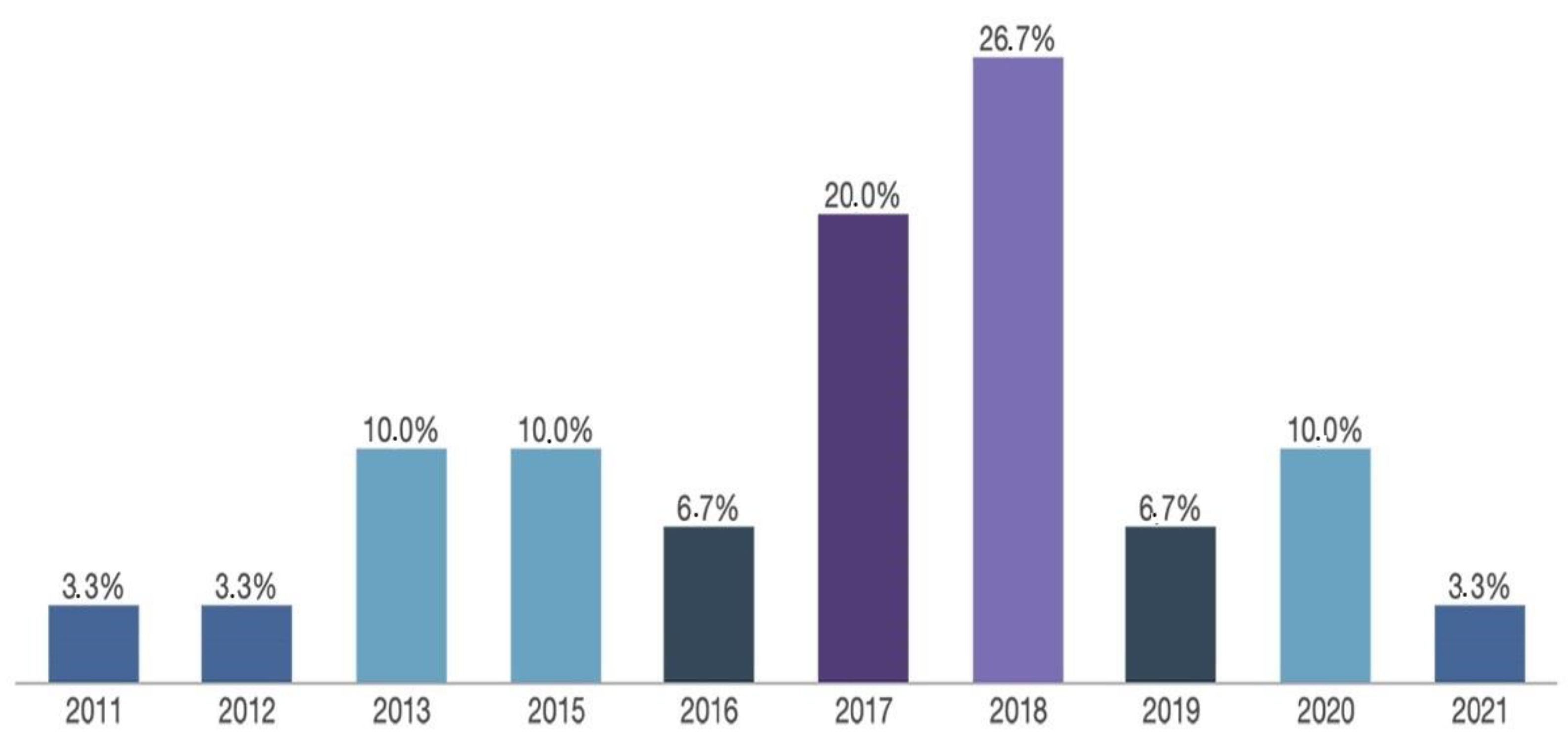

Bibliographic Data and Principal Characteristics of Articles

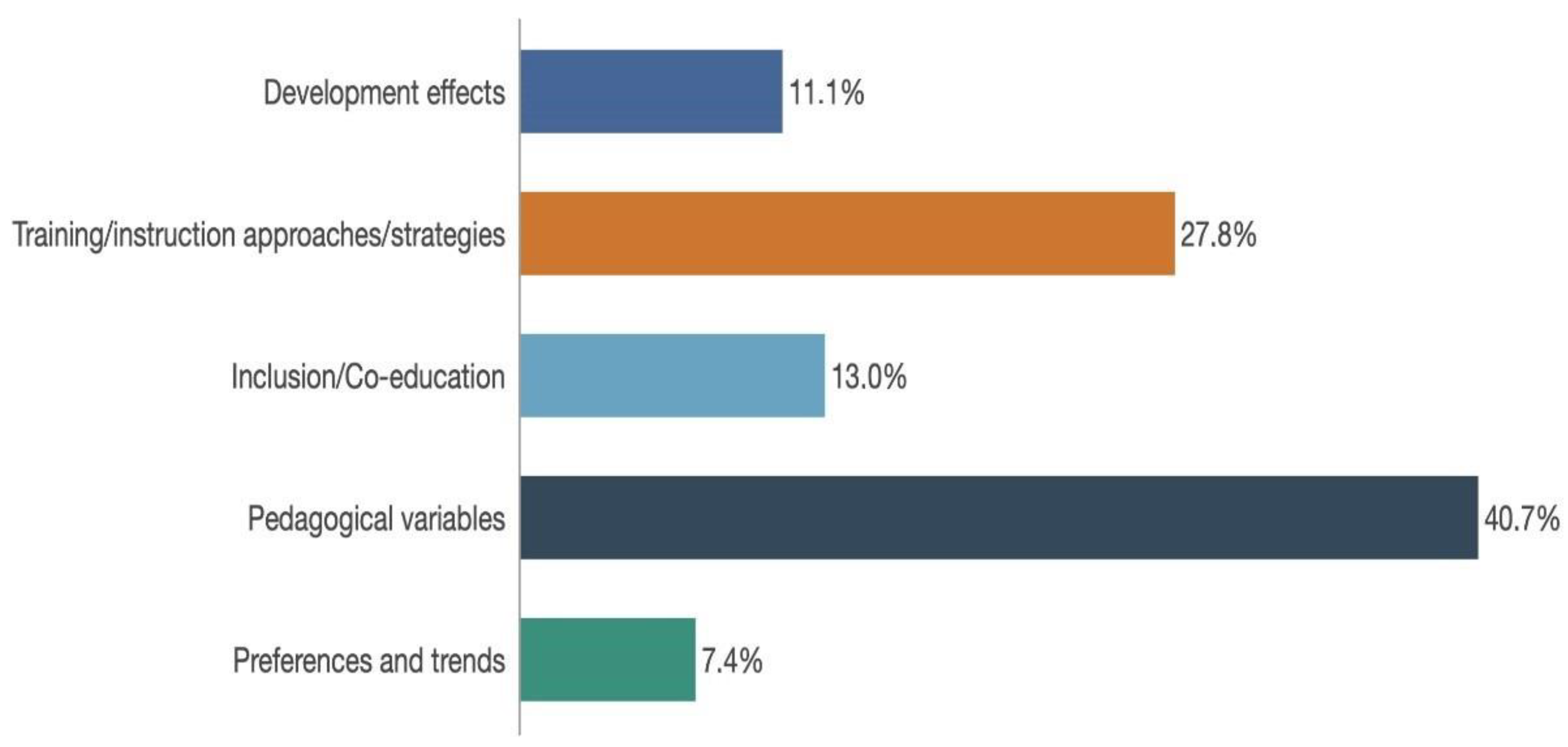

4. Analysis of Aims

5. Analysis of Results

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Franco, M.T.B.; Martín, I.M.; García, M.B. Coeducar hoy. Reflexiones desde las pedagogías feministas para la despatriarcalización del curriculum. Tend. Pedagóg. 2019, 34, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, L.A.; Croston, A. ‘It should be better all together’: Exploring strategies for ‘undoing’ gender in coeducational physical education. Sport Educ. Soc. 2012, 17, 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL). Planes de Igualdad de Género en América Latina y el Caribe: Mapas de Ruta para el Desarrollo, Observatorio de Igualdad de Género en América Latina y el Caribe. Estudios, No 1 (LC/PUB.2017/1-P/Rev.1). 2019. Available online: https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/41014/6/S1801212_es.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2021).

- European Commission. Strategic Engagement for Gender Equality: 2016–2019. Publications Office of the European Union. 2015. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/anti-trafficking/eu-policy/strategic-engagement-gender-equality-2016-2019_en (accessed on 26 October 2021).

- European Commission. Gender Equality Index 2017: Measuring Gender Equality in the European Union 2005–2015—Report. European Institute for Gender Equality. Publications Office of the European Union. 2017. Available online: https://eige.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/20177277_mh0517208enn_pdf.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2021).

- Scraton, S. Feminism(s) and PE: 25 years of Shaping Up to Womanhood. Sport Educ. Soc. 2018, 23, 638–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- With-Nielsen, N.; Pfister, G. Gender constructions and negotiations in physical education: Case studies. Sport Educ. Soc. 2011, 16, 645–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorostiza, A.I.U.; Llorente, P.A.; De Elejalde, B.G.I.; Goienola, H.M. Coeducación: Un reto para las escuelas del siglo XXI. Tend. Pedagóg. 2019, 34, 16–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, M.C.; Villa, C.F.; Gago, A.R.A. Fundamentos del Diseño Universal para el Aprendizaje Desde la Perspectiva Internacional. Rev. Bras. Educ. Esp. 2021, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colazo, C.E. Co-educación desde la perspectiva de la diversidad de género, étnico-racial, de clase, lengua y orientación sexual para América Latina. Contribución a la descolonización y despatriarcalización de la educación. Atl. Rev. Int. Estud. Fem. 2018, 2, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subirats, M. Balones Fuera: Reconstruir los Espacios Desde la Coeducación; Ediciones Octaedro: Barcelona, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Martori, M.S. Progress and challenges in gender policies and practices. Educar 2014, 50, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-López, J.A.; Gallardo-Vázquez, P. Educar en Igualdad: Prevención de la Violencia de Género en la Adolescencia. Hekademos 2019, 26, 31–39. Available online: https://bit.ly/2z6CBbv (accessed on 26 October 2021).

- Aristizabal, P.; Gómez-Pintado, A.; Ugalde, A.I.; Lasarte, G. La mirada coeducativa en la formación del profesorado. Rev. Complut. Educ. 2017, 29, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdivia, P.A.; Sánchez, A.; Alonso, J.I.; Zagalaz, M.L. Experiencias coeducativas del profesorado de educación física y relación con los contenidos de la materia. Rev. Teoría Educ. 2011, 12, 300–320. [Google Scholar]

- Domingo, S.D.D.G.; Martínez, R.A. Estereotipos del profesorado en torno al género y a la orientación sexual. Rev. Electrón. Interuniv. Form. Prof. 2017, 20, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebollo, M.A.; García-Pérez, R.; Piedra, J.; Vega, L. Diagnóstico de la cultura de género: Actitudes del profesorado hacia la igualdad. Rev. Educ. 2011, 355, 521–546. [Google Scholar]

- Pasko, V.C. A Popularidade do Handebol no Contexto Escolar e Extraescolardo Rio de Janeiro. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Gama Filho, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, L.; Miraflores, E. Propuesta de Igualdad de Género en Educación Física: Adaptaciones de las Normas en Fútbol. Retos 2018, 33, 293–297. Available online: http://bit.ly/2l1bJmF (accessed on 26 October 2021).

- EMAKUNDE. Guía de Aprendizajes del Programa Nahiko: Resumen, Conclusiones y Experiencias Piloto; Emakun-de-Instituto Vasco de la Mujer: Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sáez-Rosenkranz, I.; Barriga-Ubed, E.; Bellatti, I. Coeducation as a perspective for History teaching in Secondary Compulsory Education. Rev. Electrón. Interuniv. Form. Prof. 2019, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-López, J.A.; López-Noguero, F.; Gallardo-Vázquez, P. Pensamiento y convivencia entre géneros: Coeducación para prevenir la violencia. Multidiscip. J. Gend. Stud. 2020, 9, 263–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Pérez, R.; Rebollo Catalán, M.A.; Buzón García, O.; González-Piñal, R.; Barragán Sánchez, R.; Ruíz Pinto, E. Actitudes del alumnado hacia la igualdad de género. Rev. Investig. Educ. 2010, 28, 217–232. Available online: https://revistas.um.es/rie/article/view/98951 (accessed on 26 October 2021).

- SORKIN. La Ciencia Que se Esconde en los Saberes de las Mujeres. 2017. Available online: http://sorkinsaberes.org/sites/default/files/archivos/sorkin_guia_completa_cas.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2021).

- Bermejo, R.C.; Hernández, A.N. Sexismo y formación inicial del profesorado. Educar 2017, 55, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermejo, L. Coeducación y Juego en Educación Física. Rev. Funcae Digital 2015, 62, 10–17. Available online: http://www.fundacionfuncae.es/archivos/documentosarticulos/BERMEJO%20MARIN(2).pdf (accessed on 26 October 2021).

- Nicholls, A.R.; Polman, R.; Levy, A.R.; Taylor, J.; Cobley, S. Stressors, coping, and coping effectiveness: Gender, type of sport, and skill differences. J. Sports Sci. 2007, 25, 1521–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, R.L.; Wedgwood, N. Revisiting ‘Sport and the maintenance of masculine hegemony’. Asia-Pac. J. Health Sport Phys. Edu. 2012, 3, 181–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stride, A.; Flintoff, A. Girls, physical education and feminist praxis. In The Palgrave Handbook of Feminism and Sport, Leisure and Physical Education; Mansfield, L., Caudwell, J., Wheaton, B., Watson, B., Eds.; Pal-grave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018; pp. 855–869. [Google Scholar]

- Moral, P.A.V.; López-López, M.; Lara-Sánchez, A.J.; Sánchez, M.L.Z. Concepto de Coeducación en el Profesorado de Educación Física y Metodología Utilizada para su Trabajo. Movmento 2012, 18, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, N. Análisis de los contextos estructurales que afectan a la Educación Física e inciden en la construcción de género. Rev. Fuentes 2007, 7, 117–131. [Google Scholar]

- Blasco, D.S. Reorganizar el patio de la escuela, un proceso colectivo para la transformación social. Hábitat Soc. 2018, 11, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, J.; Sosa, P.; Porras, M. Indice cobertura P.O.S.: Procedimiento de medición de la relación entre balón y mano/P.O.S. Coverage Index: Measurement Procedure of The Relationship Between Ball and Hand. RIMCAFD 2018, 69, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-López, J.A.; Gallardo-Vázquez, P. Teorías Sobre el Juego y su Importancia Como Recurso Educativo para el Desarrollo Integral Infantil. Hekademos 2018, 24, 41–51. Available online: https://bit.ly/3aXU6ZK (accessed on 26 October 2021).

- López Estévez, R. La Coeducación en el Área de Educación Física: Revisión, Análisis y Factores Condicionantes. Rev. Digital 2012, 169, 2–12. Available online: http://www.efdeportes.com/efd169/la-coeducacion-en-educacion-fisica.htm (accessed on 26 October 2021).

- Xiao, Y.; Watson, M. Guidance on Conducting a Systematic Literature Review. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2019, 39, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, A. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pfirrmann, D.; Herbst, M.; Ingelfinger, P.; Simon, P.; Tug, S. Analysis of Injury Incidences in Male Professional Adult and Elite Youth Soccer Players: A Systematic Review. J. Athl. Train. 2016, 51, 410–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, N.L.; Ferreira, M.S.; Pasko, V.C.; De Resende, H.G. A Prática do Handbol na Cultura Físico-Esportiva de Escolares do Rio de Janeiro. Movento 2011, 17, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abernethy, B.; Schorer, J.; Jackson, R.C.; Hagemann, N. Perceptual training methods compared: The relative efficacy of different approaches to enhancing sport-specific anticipation. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 2012, 18, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slingerland, M.; Haerens, L.; Cardon, G.; Borghouts, L. Differences in perceived competence and physical activity levels during single-gender modified basketball game play in middle school physical education. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2013, 20, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eys, M.A.; Jewitt, E.; Evans, M.B.; Wolf, S.; Bruner, M.W.; Loughead, T.M. Coach-Initiated Motivational Climate and Cohesion in Youth Sport. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2013, 84, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallhead, T.; Garn, A.C.; Vidoni, C.; Youngberg, C. Game Play Participation of Amotivated Students During Sport Education. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2013, 32, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, C.; Hastie, P.A.; Mesquita, I. Towards a more equitable and inclusive learning environment in Sport Education: Results of an action research-based intervention. Sport Educ. Soc. 2015, 22, 460–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnis, F.; Lafont, L. Cooperative learning and dyadic interactions: Two modes of knowledge construction in socio-constructivist settings for team-sport teaching. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2013, 20, 459–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D.; Hannon, J.C.; Molina, S. Teaching Spatial Awareness is Small–Sided Games. Strategies 2015, 28, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, K.E.; Nagy, B.-E. Coping and Sport-motivation of Adolescent Handballers in Debrecen. Pract. Theory Syst. Educ. 2016, 11, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.; Esslinger, K. Spicing Up Your Curriculum: A Seven-Day Handball Unit. Strategies 2016, 29, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamero, M.G.; García-Ceberino, J.M.; González-Espinosa, S.; Reina, M.; Antúnez, A. Análisis de las variables pedagógicas en las tareas diseñadas para el balonmano en función del género de los docentes. Rev. Cienc. Deporte 2017, 13, 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Hastie, P.A.; Ward, J.K.; Brock, S.J. Effect of graded competition on student opportunities for participation and success rates during a season of Sport Education. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2016, 22, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, S.; Hastie, P. Students’ verbal exchanges and dynamics during Sport Education. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2016, 23, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirci, N. The Effect of School-based Exercise Practices of 9–11 Year Old Girls Students on Obesity and Health-related Quality of Life. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 5, 1323–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kristiansen, E.; Stensrud, T. Young female handball players and sport specialisation: How do they cope with the transition from primary school into a secondary sport school? Br. J. Sports Med. 2017, 51, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, V.P.; Stodden, D.F.; Rodrigues, L.P. Effectiveness of physical education to promote motor competence in primary school children. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2017, 22, 589–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, C.; Mesquita, I.; Hastie, P.A.; O’Donovan, T. Mediating Peer Teaching for Learning Games: An Action Research Intervention Across Three Consecutive Sport Education Seasons. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2018, 89, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güler, D. The evaluation of the sport preferences and tendencies of children in Amasya, Turkey. Eur. J. Phys. Educ. Sport Sci. 2018, 4, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puente-Maxera, F.; Méndez-Giménez, A.; de Ojeda, D.M. Modelo de Educación deportiva y dinámica de roles. Efectos de una intervención sobre las variables motivacionales de estudiantes de primaria. Cult. Cienc. Deporte 2018, 13, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwamberger, B.; Curtner-Smit, M. Moral Development in Sport Education: A Case Study of a Teaching-Oriented Preservice Teacher. Phys. Educ. 2018, 75, 546–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adé, D.; Ganière, C.; Louvet, B. The role of the referee in physical education lessons: Student experience and motivation. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2018, 23, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, C.; Hastie, P.A.; Mesquita, I. Scaffolding Student-Coaches’ Instructional Leadership toward Student-Centred Peer Interactions: A Yearlong Action-Research Intervention in Sport Education. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2018, 24, 269–291. Available online: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eric&AN=EJ1185446&login.asp&lang=es&site=ehost-live (accessed on 26 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Hodges, M.; Wicke, J.; Flores-Marti, I. Tactical Games Model and Its Effects on Student Physical Activity and Gameplay Performance in Secondary Physical Education. Phys. Educ. 2018, 75, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üzüm, H. Athletes’ Perception of Coaches’ Behavior and Skills About Their Sport. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 2018, 6, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Puente-Maxera, F.; Mendez-Gimenez, A.; De Ojeda, D.M. Educación Deportiva en segundo de educación primaria. Percepciones del alumnado y el profesorado respecto a una experiencia de co-enseñanza. Ágora Educ. Física Deporte 2019, 21, 74–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucukibis, H.F.; Gul, M. Study on Sports High School Students’ Motivation Levels in Sports by Some Variables. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2019, 7, 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Adigüzel, N.; Turkey, T.P.O.T.R.O. Education of star excursion balance performance among young male athletes. Afr. Educ. Res. J. 2020, 8, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárcamo, C.; Moreno, A.; del Barrio, C. Girls Do Not Sweat: The Development of Gender Stereotypes in Physical Education in Primary School. Hum. Arenas 2021, 4, 196–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEntyre, K.; Curtner-Smith, M.D.; Wind, S.A. Negotiation patterns of a preservice physical education teacher and his students during sport education. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2019, 26, 198–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, A.R.; Rodríguez, J.R. La participación en las clases de educación física la ESO y Bachillerato. Un estudio sobre un deporte tradicional (Balonmano) y un deporte alternativo (Tchoukball) (Physical education involvement in middle and high School. Comparison between a traditional. Retos 2020, 39, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J. Making a Difference? Education and ëAbilityí in Physical Education. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2004, 10, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparkes, A.C. The micropolitics of innovation in the Physical Education curriculum. In Teachers, Teaching and Control in Physical Education; Evans, J., Ed.; Falmer Press: London, UK, 1988; pp. 157–177. [Google Scholar]

- Martinek, T.; Holland, B.; Seo, G. Understanding Physical Activity Engagement in Students: Skills, Values, and Hope. [Entender la participación de la actividad física en los estudiantes: Conocimientos, valores y esperanza]. RICYDE. Rev. Int. Cienc. Deporte 2018, 15, 88–101. [Google Scholar]

- Passero, J.G.; Barreira, J.; Junior, A.C.; Galatti, L.R. Gender (In)equality: A Longitudinal Analysis of Women’s Participation in Coaching and Referee Positions in the Brazilian Women’s Basketball League (2010–2017). Cuad. Psicol. Deporte 2018, 19, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Main Author | Journal | Publication Year | Coding Segments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lima da Silva et al. [40] | Movimento | 2011 | 22 |

| Abernethy et al. [41] | Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied | 2012 | 30 |

| Slingerland et al. [42] | European Physical Education Review | 2013 | 31 |

| Eys et al. [43] | Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport | 2013 | 30 |

| Wallhead et al. [44] | Journal of Teaching in Physical Education | 2013 | 31 |

| Farias et al. [45] | Sport, Education and Society | 2015 | 25 |

| Darnis and Lafont [46] | Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy | 2015 | 25 |

| Phillips et al. [47] | Strategies: A Journal for Physical and Sport Educators | 2015 | 24 |

| Kovács, Nagy et al. [48] | Practice and Theory in Systems of Education | 2016 | 33 |

| Ramos and Esslinger [49] | Strategies: A Journal for Physical and Sport Educators | 2016 | 22 |

| Gamero et al. [50] | e-balonmano.com: Revista de Ciencias del Deporte | 2017 | 29 |

| Hastie et al. [51] | Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy | 2017 | 22 |

| Brock and Hastie [52] | European Physical Education Review | 2017 | 31 |

| Demirci et al. [53] | Universal Journal of Educational Research | 2017 | 28 |

| Kristiansen and Stensrud [54] | British Journal of Sports Medicine | 2017 | 30 |

| Lopes et al. [55] | Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy | 2017 | 31 |

| Farias et al. [56] | Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport | 2018 | 28 |

| Güler [57] | European Journal of Physical Education and Sport Science | 2018 | 24 |

| Puente-Maxera et al. [58] | Cultura, Ciencia y Deporte | 2018 | 20 |

| Schwamberger and Curtner-Smit [59] | The Physical Educator | 2018 | 25 |

| Adé et al. [60] | Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy | 2018 | 30 |

| Farias et al. [61] | European Physical Education Review | 2018 | 29 |

| Hodges et al. [62] | The Physical Educator | 2018 | 36 |

| Üzüm [63] | Journal of Education and Training Studies | 2018 | 29 |

| Puente-Maxera et al. [64] | Ágora para la Educación Física y el Deporte | 2019 | 26 |

| Kucukibis and Gul [65] | Universal Journal of Educational Research | 2019 | 28 |

| Adigüzel [66] | African Educational Research Journal | 2020 | 23 |

| Cárcamo et al. [67] | Human Arenas | 2020 | 23 |

| McEntyre et al. [68] | European Physical Education Review | 2020 | 29 |

| Robles Rodríguez and Robles Rodríguez [69] | Retos | 2021 | 23 |

| Coding System | n | Articles |

|---|---|---|

| Approaches/Strategies for Training/Instruction | 5 | Abernethy et al. (2012) [41]; Farias et al. (2018) [56]; Farias et al. (2018) [61]; Ramos and Esslinger (2016) [49]; Wallhead et al. (2013) [44] |

| Fair Play and Sporting Behaviour | 3 | Ramos and Esslinger (2016) [49]; Schwamberger and Curtner-Smit (2018) [59]; Üzüm (2018) [63] |

| Efficiency | 1 | Lopes et al. (2017) [55] |

| Skill Levels | 4 | Adé et al. (2018) [60]; Hastie et al. (2017) [51]; Lima da Silva et al. (2011) [40]; Slingerland et al. (2013) [42] |

| Education for Dynamic Equilibrium | 1 | Adigüzel (2020) [66] |

| Tactical Game Models | 1 | Hodges et al. (2018) [61] |

| Inclusion/Co-education | 1 | Farias et al. (2015) [45] |

| Beliefs/Sex-Based Differences | 6 | Cárcamo et al. (2020) [67]; Kovács and Nagy et al. (2016) [48]; Kucukibis and Gul (2019) [65]; Puente-Maxera et al. (2019) [64]; Robles Rodríguez and Robles Rodríguez (2021) [69]; Slingerland et al. (2013) [42] |

| Paedagogical Variables | 2 | Adé et al. (2018) [60]; Gamero et al. (2017) [50] |

| Participation | 1 | Wallhead et al. (2013) [44] |

| Lessons Taught | 1 | Gamero et al. (2017) [50] |

| Role of Teacher/Coach | 3 | Farias et al. (2018) [45]; Schwamberger and Curtner-Smit (2018) [59]; Üzüm (2018) [63] |

| Basic Abilities and Concepts | 5 | Farias et al. (2018) [61]; Phillips et al. (2015) [47]; Puente-Maxera et al. (2019) [64]; Ramos and Esslinger (2016) [49]; Üzüm (2018) [63] |

| Teacher-Pupil Interaction | 1 | McEntyre et al. (2020) [68] |

| Confrontation and Motivation | 4 | Adé et al. (2018) [60]; Kovács and Nagy et al. (2016) [48]; Kucukibis and Gul (2019) [65]; Wallhead et al. (2013) [44] |

| Spoken Interchanges | 2 | Brock and Hastie (2017) [52]; Darnis and Lafont (2015) [46] |

| Cohesion and Motivational Atmosphere | 1 | Eys et al. (2013) [42] |

| Transition | 1 | Kristiansen and Stensrud (2017) [54] |

| Preferences and Trends | 3 | Güler (2018) [57]; Puente-Maxera et al. (2019) [64]; Robles Rodríguez and Robles Rodríguez (2021) [69] |

| Type of Sport (Individual or Team) | 1 | Kucukibis and Gul (2019) [65] |

| Developmental Effects | 1 | Farias et al. (2018) [45] |

| Immune System and Psychology | 1 | Kovács and Nagy et al. (2016) [48] |

| Development of Motor Skills and Physical Fitness | 1 | Lopes et al. (2017) [55] |

| Cognitive and Psychomotor Development | 1 | Phillips et al. (2015) [47] |

| Health | 2 | Demirci et al. (2017) [53]; Puente-Maxera et al. (2018) [58] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arias, A.R.; Soto, D.; Ferreira, C. A Systematic Review of Co-Educational Models in School Handball. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11438. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111438

Arias AR, Soto D, Ferreira C. A Systematic Review of Co-Educational Models in School Handball. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(21):11438. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111438

Chicago/Turabian StyleArias, Ana R., Diego Soto, and Camino Ferreira. 2021. "A Systematic Review of Co-Educational Models in School Handball" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 21: 11438. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111438

APA StyleArias, A. R., Soto, D., & Ferreira, C. (2021). A Systematic Review of Co-Educational Models in School Handball. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11438. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111438