The Development of a Nutrition Screening Tool for Mental Health Settings Prone to Obesity and Cardiometabolic Complications: Study Protocol for the NutriMental Screener

Abstract

:1. Introduction

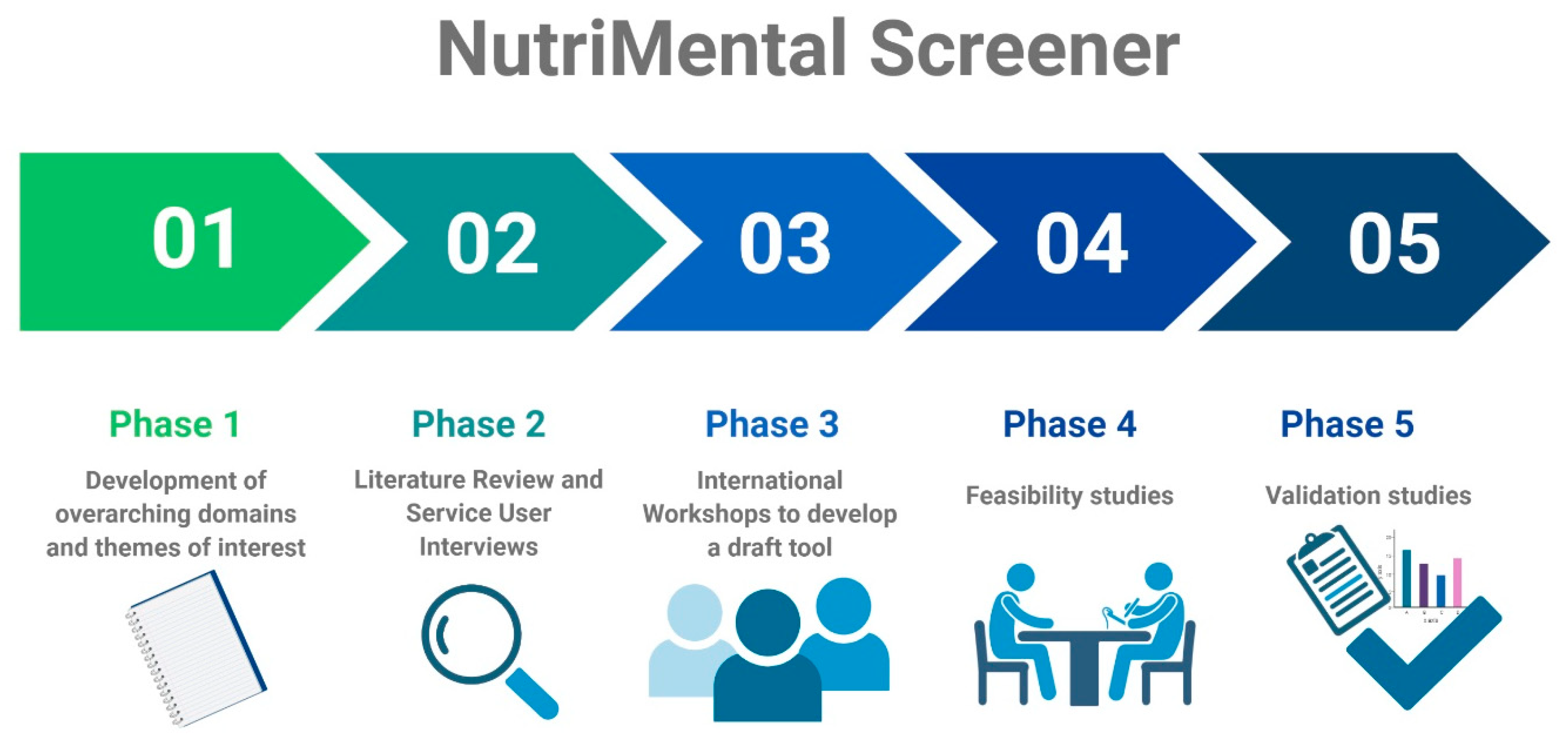

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Phase I: Development of Overarching Domains and Themes of Interest

2.2. Phase II: Literature Review and Service User Interviews

2.3. Phase III: International Workshops to Develop a Draft Tool

2.4. Phase IV: Feasibility Studies

2.5. Phase V: Validation Studies

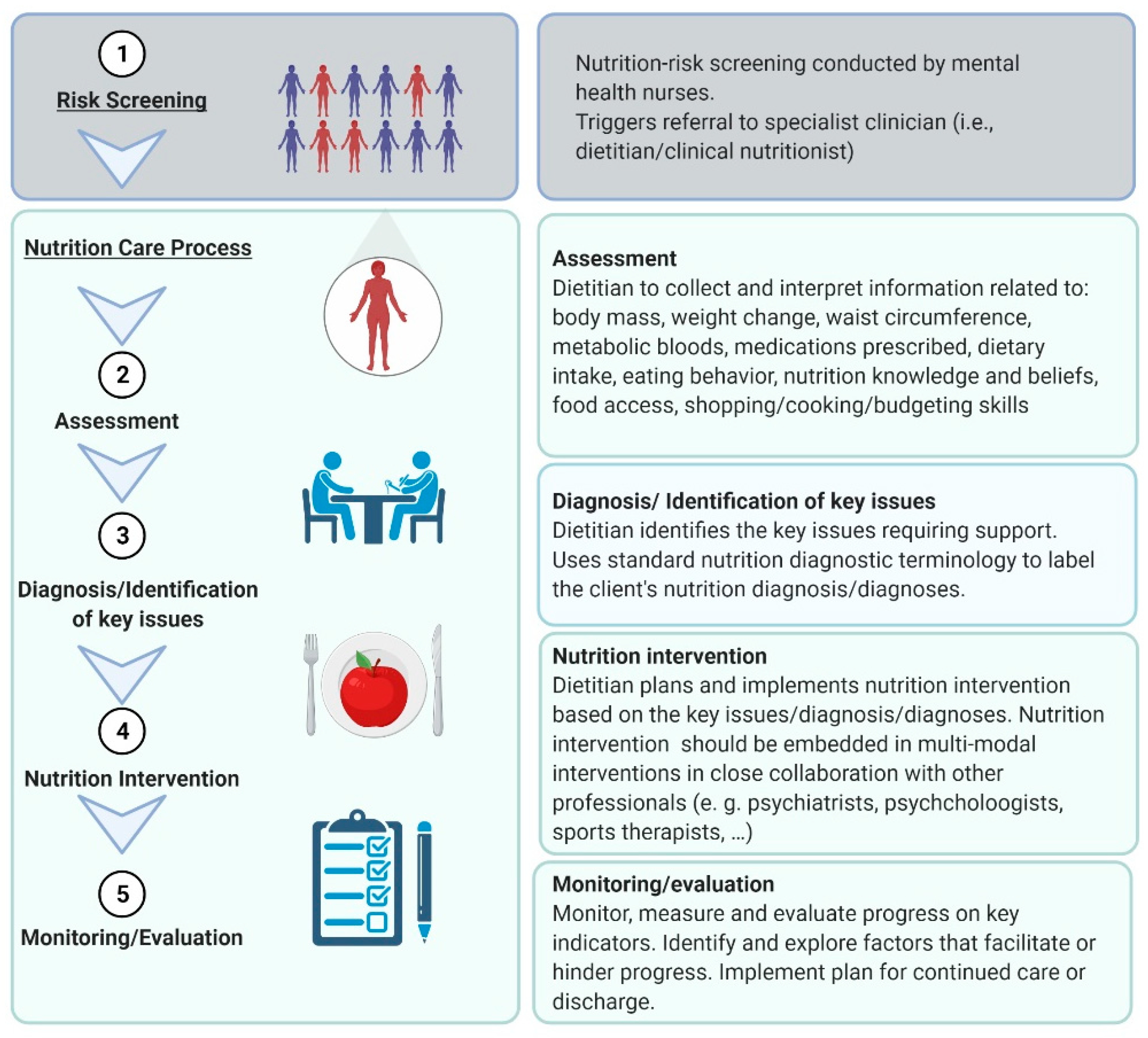

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barker, L.A.; Gout, B.S.; Crowe, T.C. Hospital malnutrition: Prevalence, identification and impact on patients and the healthcare system. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2011, 8, 514–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cuerda, C.; Velasco, C.; Merchan-Naranjo, J.; Garcia-Peris, P.; Arango, C. The effects of second-generation antipsychotics on food intake, resting energy expenditure and physical activity. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 68, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountaine, R.J.; Taylor, A.E.; Mancuso, J.P.; Greenway, F.L.; Byerley, L.O.; Smith, S.R.; Most, M.M.; Fryburg, D.A. Increased food intake and energy expenditure following administration of olanzapine to healthy men. Obesity 2010, 18, 1646–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluge, M.; Schuld, A.; Himmerich, H.; Dalal, M.; Schacht, A.; Wehmeier, P.M.; Hinze-Selch, D.; Kraus, T.; Dittmann, R.W.; Pollmächer, T. Clozapine and olanzapine are associated with food craving and binge eating: Results from a randomized double-blind study. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2007, 27, 662–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morylowska-Topolska, J.; Ziemiński, R.; Molas, A.; Gajewski, J.; Flis, M.; Stelmach, E.; Karakuła-Juchnowicz, H. Schizophrenia and anorexia nervosa—Reciprocal relationships. A literature review. Psychiatr. Pol. 2017, 51, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouidrat, Y.; Amad, A.; Lalau, J.D.; Loas, G. Eating disorders in schizophrenia: Implications for research and management. Schizophr. Res. Treat. 2014, 2014, 791573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paans, N.P.G.; Bot, M.; van Strien, T.; Brouwer, I.A.; Visser, M.; Penninx, B. Eating styles in major depressive disorder: Results from a large-scale study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2018, 97, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sentissi, O.; Viala, A.; Bourdel, M.C.; Kaminski, F.; Bellisle, F.; Olié, J.P.; Poirier, M.F. Impact of antipsychotic treatments on the motivation to eat: Preliminary results in 153 schizophrenic patients. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2009, 24, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teasdale, S.B.; Ward, P.B.; Samaras, K.; Firth, J.; Stubbs, B.; Tripodi, E.; Burrows, T.L. Dietary intake of people with severe mental illness: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2019, 214, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Correll, C.U.; Manu, P.; Olshanskiy, V.; Napolitano, B.; Kane, J.M.; Malhotra, A.K. Cardiometabolic risk of second-generation antipsychotic medications during first-time use in children and adolescents. JAMA 2009, 302, 1765–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Álvarez-Jiménez, M.; González-Blanch, C.; Crespo-Facorro, B.; Hetrick, S.; Rodriguez-Sánchez, J.M.; Pérez-Iglesias, R.; Luis, J. Antipsychotic-induced weight gain in chronic and first-episode psychotic disorders. CNS Drugs 2008, 22, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strassnig, M.; Kotov, R.; Cornaccio, D.; Fochtmann, L.; Harvey, P.D.; Bromet, E.J. 20-year progression of BMI in a county-wide cohort people with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder identified at their first episode of psychosis. Bipolar Disord. 2017, 19, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Hert, M.; Detraux, J.; Van Winkel, R.; Yu, W.; Correll, C.U. Metabolic and cardiovascular adverse effects associated with antipsychotic drugs. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2012, 8, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stubbs, B.; Williams, J.; Gaughran, F.; Craig, T. How sedentary are people with psychosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 2016, 171, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lawrence, D.; Mitrou, F.; Zubrick, S.R. Smoking and mental illness: Results from population surveys in Australia and the United States. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mauri, M.; Volonteri, L.S.; De Gaspari, I.F.; Colasanti, A.; Brambilla, M.A.; Cerruti, L. Substance abuse in first-episode schizophrenic patients: A retrospective study. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2006, 2, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vancampfort, D.; Stubbs, B.; Mitchell, A.; De Hert, M.; Wampers, M.; Ward, P.B.; Rosenbaum, S.; Correll, C.U. Risk of metabolic syndrome and its components in people with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry 2015, 14, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, D.; Hancock, K.J.; Kisely, S. The gap in life expectancy from preventable physical illness in psychiatric patients in Western Australia: Retrospective analysis of population based registers. BMJ 2013, 346, f2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Hert, M.; Correll, C.U.; Bobes, J.; Cetkovich-Bakmas, M.; Cohen, D.; Asai, I.; Detraux, J.; Gautam, S.; Möller, H.-J.; Ndetei, D.M.; et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry Off. J. World Psychiatr. Assoc. 2011, 10, 52–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jones, S.; Howard, L.; Thornicroft, G. Diagnostic overshadowing: Worse physical health care for people with mental illness. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2008, 118, 169–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornquast, C.; Tomzik, J.; Reinhold, T.; Walle, M.; Mönter, N.; Berghöfer, A. To what extent are psychiatrists aware of the comorbid somatic illnesses of their patients with serious mental illnesses? A cross-sectional secondary data analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mörkl, S.; Stell, L.; Buhai, D.V.; Schweinzer, M.; Wagner-Skacel, J.; Vajda, C.; Lackner, S.; Bengesser, S.A.; Lahousen, T.; Painold, A.; et al. An Apple a Day?: Psychiatrists, Psychologists and Psychotherapists Report Poor Literacy for Nutritional Medicine: International Survey Spanning 52 Countries. Nutrients 2021, 13, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandré, C.; Coldefy, M. Disparities in the Use of General Somatic Care among Individuals Treated for Severe Mental Disorders and the General Population in France. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hancox, L.E.; Lee, P.S.; Armaghanian, N.; Hirani, V.; Wakefield, G. Nutrition risk screening methods for adults living with severe mental illness: A scoping review. Nutr. Diet. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dott, S.G.; Weiden, P.; Hopwood, P.; Awad, A.G.; Hellewell, J.S.; Knesevich, J.; Kopala, L.; Miller, A.; Salzman, C. An innovative approach to clinical communication in schizophrenia: The approaches to schizophrenia communication checklists. CNS Spectr. 2001, 6, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowell, A.; Long, C.; Chance, L.; Dolley, O. Identification of nutritional risk by nursing staff in secure psychiatric settings: Reliability and validity of St Andrew’s Nutrition Screening Instrument. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2012, 19, 722–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PROSPERO: International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews. 2021. CRD42021232762. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021232762 (accessed on 7 October 2021).

- PROSPERO: International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews. 2018. CRD42018095028. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42018095028 (accessed on 7 October 2021).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tilburg, U.; Hambleton, R.K. Translating tests: Some practical guidelines. Eur. Psychol. 1996, 1, 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Kruizenga, H.M.; Seidell, J.C.; de Vet, H.C.; Wierdsma, N.J.; van der Schueren, M.A.V.B.D. Development and validation of a hospital screening tool for malnutrition: The short nutritional assessment questionnaire (SNAQ). Clin. Nutr. 2005, 24, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reber, E.; Gomes, F.; Vasiloglou, M.F.; Schuetz, P.; Stanga, Z. Nutritional risk screening and assessment. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mitchell, A.J.; Delaffon, V.; Vancampfort, D.; Correll, C.U.; De Hert, M. Guideline concordant monitoring of metabolic risk in people treated with antipsychotic medication: Systematic review and meta-analysis of screening practices. Psychol. Med. 2012, 42, 125–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melamed, O.C.; Wong, E.N.; LaChance, L.R.; Kanji, S.; Taylor, V.H. Interventions to Improve Metabolic Risk Screening Among Adult Patients Taking Antipsychotic Medication: A Systematic Review. Psychiatr. Serv. 2019, 70, 1138–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teasdale, S.; Firth, J. Recommendations for dietetics in mental healthcare. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 33, 149–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller-Stierlin, A.S.; Teasdale, S.B.; Dinc, U.; Moerkl, S.; Prinz, N.; Becker, T.; Kilian, R. Feasibility and Acceptability of Photographic Food Record, Food Diary and Weighed Food Record in People with Serious Mental Illness. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teasdale, S.; Mörkl, S.; Müller-Stierlin, A.S. Nutritional Psychiatry in the treatment of psychotic disorders: Current hypotheses and research challenges. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2020, 5, 100070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teasdale, S.B.; Ward, P.B.; Samaras, K. Dietary intervention in the dystopian world of severe mental illness: Measure for measure, then manage. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2017, 135, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Domain | Themes |

|---|---|

| Risk factors related to disordered eating behavior | food preoccupation little appetite (undernutrition) much appetite (overnutrition) speed of eating loss of control eating food craving night eating eating structure food preferences |

| Risk factors related to eating behavior and connected emotions | eating shame/guilt emotional eating eating for a positive outcome |

| Risk factors related to body weight/shape and connected emotions | weight change thinness weight preoccupation body dissatisfaction |

| Risk factors related to general health state | memory/concentration swallow ability dry mouth/hypersalivation bowel habits other bodily issues |

| Risk factors related to the treatment of mental disorder | medication |

| Risk factors related to lifestyle | dieting compensatory behaviors exercise sleep hygiene |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Teasdale, S.B.; Moerkl, S.; Moetteli, S.; Mueller-Stierlin, A. The Development of a Nutrition Screening Tool for Mental Health Settings Prone to Obesity and Cardiometabolic Complications: Study Protocol for the NutriMental Screener. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11269. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111269

Teasdale SB, Moerkl S, Moetteli S, Mueller-Stierlin A. The Development of a Nutrition Screening Tool for Mental Health Settings Prone to Obesity and Cardiometabolic Complications: Study Protocol for the NutriMental Screener. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(21):11269. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111269

Chicago/Turabian StyleTeasdale, Scott B., Sabrina Moerkl, Sonja Moetteli, and Annabel Mueller-Stierlin. 2021. "The Development of a Nutrition Screening Tool for Mental Health Settings Prone to Obesity and Cardiometabolic Complications: Study Protocol for the NutriMental Screener" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 21: 11269. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111269

APA StyleTeasdale, S. B., Moerkl, S., Moetteli, S., & Mueller-Stierlin, A. (2021). The Development of a Nutrition Screening Tool for Mental Health Settings Prone to Obesity and Cardiometabolic Complications: Study Protocol for the NutriMental Screener. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11269. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111269