“My 9 to 5 Job Is Birth Work”: A Case Study of Two Compensation Approaches for Community Doula Care

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Benefits of Doula Care

1.2. The Role of Community Doulas in Reducing Health Inequities

1.3. Compensation Approaches for Doulas

1.4. Implications for Community Doula Care

2. Materials and Methods

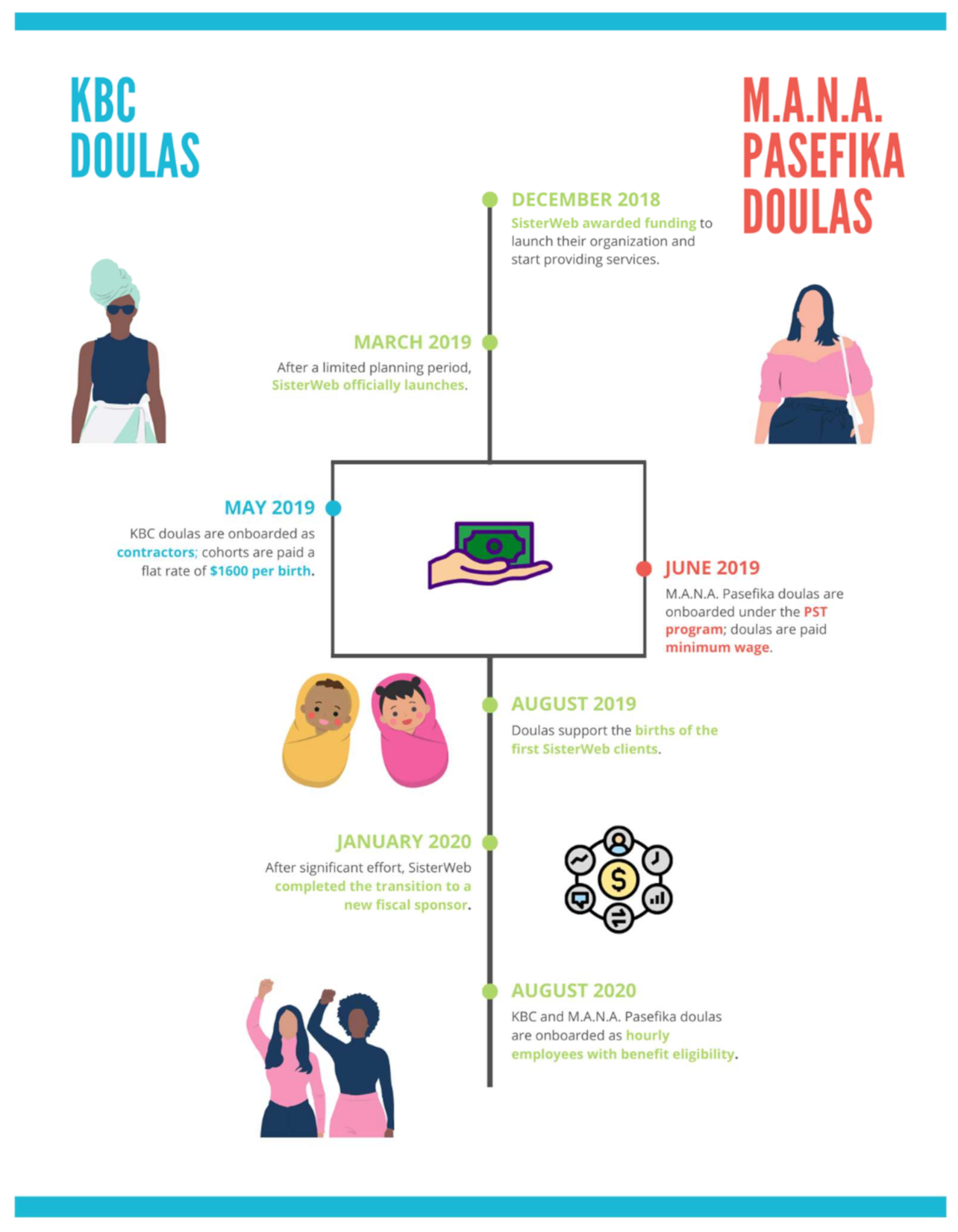

2.1. Case Description

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Independent Contractor Compensation Approach

3.1.1. Rationale

“We basically—again, with a week’s notice—pulled together a proposal. At that moment in time, we based our doula program a little bit off of what private doulas offer. Also, reading about other community programs… So, we looked at, okay, real quick, what is everybody else doing? We created a mash-up of some of the different elements of their programs and thought—again, without a long, slow process—that was what our best guess was.”(Leader)

“In the beginning we said, hey, this is how it’s being paid. It’s not really fair. It doesn’t even make sense for us, and we don’t have another system because we have to start working. And we are committed to changing and figuring out a different system, but in order for us to start, we have to start somewhere. If you want to get paid to do this, we have to start somewhere, and this is how we have to start. This is the only option right now.”(Leader)

3.1.2. Financial Challenges

“It will depend on the client, because there are some that don’t require a lot of the consistent communication. There are some that know exactly what they want you for, and that’s what you’re there for. There are some that don’t know anything and call you… at 4:00 in the morning because they up with cravings and don’t know what to do, or they’re breaking down about something that they can’t control. So, it really just depends on the client.”(Doula)

“Honestly, if I have the time, like I’m willing to do it. It’s a lot of time and that is one of the drawbacks when you don’t get paid hourly, but like, personally, as long as like, I have availability, I’m willing to go… We kind of like, I guess, base it on urgency of [the] client in the situation. Like, if [a doula] see[s] their client’s really anxious or they’re stressed.”(Doula)

“I would say that there should be a little more compensation for like the trainings and stuff because we don’t get compensated for that, but we do get paid for the births and the prenatals. So, I guess when you signed up for it, you kinda knew that that’s how it was gonna go, but I would say, I would like some compensation for the trainings as well. Because that’s like extra days that I’m not working at my other job, that I could be making money.”(Doula)

“Say my client dropped out. I don’t have a birth this month. I still gotta go to my professional development and put two hours or eight hours, you know, six hours in a training.”(Doula)

“I’m lucky right now, because with my main job, they are very flexible. So, if I have to go to a birth, just need to give them notice. I don’t have to, and I don’t even have to give them that much notice, because the dad at work, he can work from home at any time. He always told me like from the beginning, if anything ever comes up, just call me and we could always like, I can always rearrange my schedule and work from home.”(Doula)

“I changed jobs toward the end of last year. When I first got, like, interviewed with the job, I was very transparent with them about…what I do on the side. I’m on call, that means, you know, I may have to leave unexpectedly. And the manager at the time was cool with it. But they did change management earlier this year, and he’s not as cool with it, so it’s kinda forcing me to look for another 9 to 5. That’s one of the biggest struggles of it, is just like, finding something where they’re comfortable with what you do on the side.”(Doula)

“I wish there was some like compensation around like travel. I think that’s my biggest thing right now… especially because Lyft’s and Uber’s like quite expensive, and they add up.”(Doula)

“Being able to work with my community has meant everything to me. Because that was like, when I became a doula, that was what I really wanted to focus on, was like working with Black women and people in my neighborhood and stuff like that… it was just hard to be able to work with my community but also like get paid, to be able to live and stay in my community. So, [working with SisterWeb] has been kind of the best of both worlds.”(Doula)

“I love this [work] so much that I would do it for free, but just like… knowing that [working with SisterWeb] can help me a little bit, like, take off the burden of that insecurity, like, that is honestly like a dream come true for me.”(Doula)

3.1.3. Organizational Administrative and Ethical Challenges

“We realized that there were major flaws in the program in how doulas were invoicing and getting paid that were just not sustainable. They didn’t align with our ultimate goal of the program, which was dignified employment, to turn birth work into a career. There just wasn’t enough stability. There wasn’t enough guarantee of payment. The timing of the payments was all off.”(Leader)

“The doulas ain’t been paid since December… It’s not affecting them meeting with their clients. It’s not affecting their output. But I definitely see it affecting their state, their emotional state in terms of like, ‘Hey, I put them invoices in. I’m getting emails. Hey, I’m getting the invoices in, when we gonna get paid?’”(Doula)

“For SisterWeb, specifically [COVID-19] presented a whole bunch of questions for us around risk and… that we may be asking our doulas to assume a certain amount of risk by going into the hospital during a pandemic when we just didn’t feel comfortable with the amount of financial and healthcare support that we were able to provide them. Where it was, like, for hospital workers, nurses, doctors, midwives—they have salaries and health benefits and extra sick leave.”(Leader)

“One of our biggest pushes in why we weren’t ready to go back into the hospitals is because our doulas were independent contractors. We weren’t sure who had health insurance, and what people’s living situations were like, what their own health was like, their own levels of comfort and safety in working in the environment.”(Leader)

3.2. Hourly Employee with Benefits Compensation Approach

3.2.1. Rationale

“Our ultimate goal of the program, [is] dignified employment, to turn birth work into a career.”(Leader)

“We have always been very clear that our doulas get paid to get trained and get paid to do the work that they do. And they are from their own communities, serve their communities.”(Leader)

“Even though this is nonprofit, for me, a for profit would be making sure that my staff would be paid and get the hours that they need and the benefits that they need and that they’re cared for, and they have the support that they need to do the work that they want to do.”(Leader)

“Seeing the numbers play out, and what [it] would cost to put doulas on as staff as employees… I was like, there’s still no way to do it, because if we do that, that shrinks down the budget… I only have a certain dollar amount, and a dollar amount is a dollar amount, and that would shrink my amount to pay our doulas.”(Leader)

“The steps that we had to go through to actually change the model were pretty slow because, for one, we didn’t have the money in the bank to turn everyone into an employee. So, there was an incredible amount of fundraising that had to happen to supplement that initial funding that we got.”(Leader)

“We ended up having to switch fiscal sponsors. That, also, was a huge energy and time drain on the organization, especially on the leadership… I would say hundreds of hours that we all spent filling out paperwork.”(Leader)

3.2.2. Doulas’ Experiences as Benefited, Hourly Employees of SisterWeb

“I know that I’m going to get paid a certain amount every two weeks. So, I like that. It’s reliable money.”(Doula)

“I like the consistency of the pay now, whereas when we were doing the invoicing, it was whenever you had a birth, you submit it. And then sometimes, I feel like, when we did the invoices, they would take a long time [to process]. So, it was a hit or miss with that.”(Doula)

“Some clients got you working hella extra… So, I think [the hourly model is] more beneficial because you actually get compensated for what you’re doing. And it’s not this shift of you could put in 20 h with one client and get the same little 1600 USD or whatever it was. Or you could put in 5 h and get the same amount.”(Doula)

“We get paid time off, we get sick leave. We get health benefits, dental benefits… beforehand, we didn’t have a lot of those extra perks with being an employee, rather than being an independent contractor. So that’s really good.”(Doula)

“I appreciate this [health insurance] because it just has [coverage] for my kids, and emergency stuff, and all of it, just kind of included… so I was able to put them on [my insurance]. And that was a big deal.”(Doula)

“It’s just tricky trying to write down exactly what you do during the day, because I have to write it down on a spreadsheet… Say you talked to your client on the phone for five minutes. And then you talked to your other client for an hour. And then you talked to your other client for seven minutes on the phone. Just trying to figure out, so how much time is that that you spent on that particular work? And then how do you translate that into the spreadsheet? And then how do you translate that into [the timekeeping system], where you log your hours?”(Doula)

“This is a legit job now, going from that shift of being a contractor to then, ‘No, you’re an employee. You need to figure out how you’re getting all these hours done. If I call you during the hours that you’re working, you should be working.’ Because it was so much more free before… Doulas who we’ve hired that come straight into an employee position, they get it.But doulas who have gone through all of these changes with us, it’s a lot harder to shift.”(Doula)

3.2.3. Sustainability

“My favorite thing about working with SisterWeb is that my 9 to 5 job is birth work. It’s like, usually most people have to choose between doing reproductive justice stuff, or having a 9 to 5, where you do both and burn the candle at both ends. And I just love that I’m getting paid a wage that I can with ease afford my rent. With ease buy groceries. I’m not having to scrounge for bills, just because I’m doing birth work.”(Doula)

“I never realized how long I was actually sitting there, inputting all of these notes from the birth. I’m like, ‘Oh my God, this takes so much longer than I thought it takes,’ when you’re actually keeping track of it. That and other mundane tasks, like filling out a referral, or texting a client. Or we never realized how what seems like minutes is actually, when you add it all up, it’s hours.”(Doula)

“[A]nother reason [it’s not enough] is just living in San Francisco. Another reason is the added work that we do for program development now. I feel like we’re building our skills. So not only are we doulas, but we’re, like, I would say, community organizers.”(Doula)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morton, C.H.; Clift, E.G. Introduction. In Birth Ambassadors: Doulas and the Re-Emergence of Woman-Supported Birth in America; Praeclarus Press: Amarillo, TX, USA, 2014; pp. 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher, J.; Simkin, P. 2002 DONA International Board of Directors. In Position Paper: The Postpartum Doula’s Role in Maternity Care; DONA International: Chicago, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Simkin, P. Position Paper: The Birth Doula’s Role in Maternity Care; DONA International: Chicago, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chor, J.; Goyal, V.; Roston, A.; Keith, L.; Patel, A. Doulas as Facilitators: The Expanded Role of Doulas into Abortion Care. J. Fam. Plann. Reprod. Health Care 2012, 38, 123–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lantz, P.M.; Low, L.K.; Varkey, S.; Watson, R.L. Doulas as Childbirth Paraprofessionals: Results from a National Survey. Womens Health Issues 2005, 15, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, M. What Is a Doula and Should You Hire One for Your Baby’s Birth? Available online: https://www.whattoexpect.com/pregnancy/hiring-doula (accessed on 25 October 2020).

- Bey, A.; Brill, A.; Porchia-Albert, C.; Gradilla, M.; Strauss, N. Advancing Birth Justice: Community-Based Doula Models as a Standard of Care for Ending Racial Disparities; Every Mother Counts: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bakst, C.; Moore, J.E.; George, K.E.; Shea, K. Community-Based Maternal Support. Services: The Role of Doulas and Community Health Workers in Medicaid; Institute for Medicaid Innovation: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bohren, M.; Hofmeyr, G.; Sakala, C.; Fukuzawa, R.; Cuthbert, A. Continuous Support for Women during Childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 7, CD003766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozhimannil, K.B.; Hardeman, R.R.; Attanasio, L.B.; Blauer-Peterson, C.; O’Brien, M. Doula Care, Birth Outcomes, and Costs Among Medicaid Beneficiaries. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, e113–e121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhimannil, K.B.; Attanasio, L.B.; Jou, J.; Joarnt, L.K.; Johnson, P.J.; Gjerdingen, D.K. Potential Benefits of Increased Access to Doula Support during Childbirth. Am. J. Manag. Care 2014, 20, e340–e352. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kozhimannil, K.B.; Hardeman, R.R.; Alarid-Escudero, F.; Vogelsang, C.A.; Blauer-Peterson, C.; Howell, E.A. Modeling the Cost-Effectiveness of Doula Care Associated with Reductions in Preterm Birth and Cesarean Delivery. Birth 2016, 43, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozhimannil, K.B.; Attanasio, L.B.; Hardeman, R.R.; O’Brien, M. Doula Care Supports Near-Universal Breastfeeding Initiation among Diverse, Low-Income Women. J. Midwifery Womens Health 2013, 58, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berwick, D.M.; Nolan, T.W.; Whittington, J. The Triple Aim: Care, Health, and Cost. Health Aff. Proj. Hope 2008, 27, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Declercq, E.R.; Sakala, C.; Corry, M.P.; Applebaum, S.; Herrlich, A. Listening to Mothers III: Pregnancy and Childbirth; Childbirth Connection: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sakala, C.; Declercq, E.R.; Turon, J.M.; Corry, M.P. Listening to Mothers in California: Full Survey Report, 2018; National Partnership for Women & Families: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, C.J.; Harper, M.A.; Atkinson, S.M.; Bell, E.A.; Brown, H.L.; Hage, M.L.; Mitra, A.G.; Moise, K.J.; Callaghan, W.M. Preventability of Pregnancy-Related Deaths: Results of a State-Wide Review. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 106, 1228–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creanga, A.A.; Syverson, C.; Seed, K.; Callaghan, W.M. Pregnancy-Related Mortality in the United States, 2011–2013. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 130, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somer, S.J.H.; Sinkey, R.G.; Bryant, A.S. Epidemiology of Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Severe Maternal Morbidity and Mortality. Semin. Perinatol. 2017, 41, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDorman, M.F.; Mathews, T.J. Understanding Racial and Ethnic Disparities in U.S. Infant Mortality Rates. NCHS Data Brief. 2011, 74, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J.A.; Hamilton, B.E.; Osterman, M.J.K.; Driscoll, A.K. Births: Final Data for 2019. Natl. Vital Stat. Rep. 2021, 70, 1–51. [Google Scholar]

- Crear-Perry, J.; Correa-de-Araujo, R.; Lewis Johnson, T.; McLemore, M.R.; Neilson, E.; Wallace, M. Social and Structural Determinants of Health Inequities in Maternal Health. J. Womens Health 2021, 30, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, E.A. Reducing Disparities in Severe Maternal Morbidity and Mortality. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 61, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willis, E.; McManus, P.; Magallanes, N.; Johnson, S.; Majnik, A. Conquering Racial Disparities in Perinatal Outcomes. Clin. Perinatol. 2014, 41, 847–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozhimannil, K.B.; Vogelsang, C.A.; Hardeman, R.R.; Prasad, S. Disrupting the Pathways of Social Determinants of Health: Doula Support during Pregnancy and Childbirth. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. JABFM 2016, 29, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Health Connect One. Sustainable Funding for Doula Programs: A Study; Health Connect One: Chicago, IL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gebel, C.; Hodin, S. Expanding Access to Doula Care: State of the Union. Available online: https://www.mhtf.org/2020/01/08/expanding-access-to-doula-care/ (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- Kozhimannil, K.B.; Vogelsang, C.A.; Hardeman, R.R. Medicaid Coverage of Doula Services in Minnesota: Preliminary Findings from the First Year; Interim Report to the Minnesota Department of Human Services; University of Minnesota School of Public Health: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Minnesota Department of Human Services. Doula Services. Available online: https://www.dhs.state.mn.us/main/idcplg?IdcService=GET_DYNAMIC_CONVERSION&RevisionSelectionMethod=LatestReleased&dDocName=DHS16_190890 (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- Oregon Health Authority. Oregon Medicaid Reimbursement for Doula Services; Medicaid Programs; Health Systems Division, Oregon Health Authority: Salem, OR, USA, 2018.

- State of California. Health and Human Services, 2021–2022 State Budget. Available online: http://www.ebudget.ca.gov/2021-22/pdf/Enacted/GovernorsBudget/4000.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- New York State Department of Health. New York State Doula Pilot Program. Available online: https://www.health.ny.gov/health_care/medicaid/redesign/doulapilot/index.htm (accessed on 26 June 2021).

- National Health Law Program. Doula Medicaid Project. Available online: https://healthlaw.org/doulamedicaidproject/ (accessed on 29 January 2021).

- SisterWeb San Francisco Community Doula Network. Our Purpose & Beliefs. Available online: https://www.sisterweb.org/about-us (accessed on 6 October 2021).

- Luminaire Group; Center for Equitable Evaluation; Dorothy A Johnson Center for Philanthropy. Equitable Evaluation FrameworkTM Framing Paper; Equitable Evaluation Initiative: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): A 32-Item Checklist for Interviews and Focus Groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Beebe, J. Rapid Assessment Process. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods; Given, L., Ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, A.B. Qualitative Methods in Rapid Turn-around Health Services Research. Available online: https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/780-notes.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- Gómez, A.M.; Arteaga, S.; Marshall, C.; Arcara, J.; Cuentos, A.; Armstead, M.; Jackson, A. SisterWeb San Francisco Community Doula Network: Process. Evaluation Report; Sexual Health and Reproductive Equity Program; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications Ltd.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- SisterWeb San Francisco Community Doula Network SisterWeb COVID Impact Report; SisterWeb San Francisco Community Doula Network: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2021.

- Chen, A.; Robles-Fradet, A.; Arega, H. Building a Successful Program for Medi-Cal Coverage for Doula Care: Findings from a Survey of Doulas in California; National Health Law Program: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Smid, M.; Campero, L.; Cragin, L.; Gonzalez Hernandez, D.; Walker, D. Bringing Two Worlds Together: Exploring the Integration of Traditional Midwives as Doulas in Mexican Public Hospitals. Health Care Women Int. 2010, 31, 475–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, C. Professional Ambivalence among Care Workers: The Case of Doula Practice. Health 2021, 25, 306–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapple, W.; Gilliland, A.; Li, D.; Shier, E.; Wright, E. An Economic Model of the Benefits of Professional Doula Labor Support in Wisconsin Births. WMJ 2013, 112, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Greiner, K.S.; Hersh, A.R.; Hersh, S.R.; Remer, J.M.; Gallagher, A.C.; Caughey, A.B.; Tilden, E.L. The Cost-Effectiveness of Professional Doula Care for a Woman’s First Two Births: A Decision Analysis Model. J. Midwifery Womens Health 2019, 64, 410–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozhimannil, K.B.; Hardeman, R.R. Coverage for Doula Services: How State Medicaid Programs Can Address Concerns about Maternity Care Costs and Quality. Birth 2016, 43, 97–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Safon, C.; McCloskey, L.; Ezekwesili, C.; Feyman, Y.; Gordon, S.H. Doula Care Saves Lives, Improves Equity, and Empowers Mothers. State Medicaid Programs Should Pay for It. Health Affairs Blog. Available online: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20210525.295915/full/ (accessed on 26 June 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gomez, A.M.; Arteaga, S.; Arcara, J.; Cuentos, A.; Armstead, M.; Mehra, R.; Logan, R.G.; Jackson, A.V.; Marshall, C.J. “My 9 to 5 Job Is Birth Work”: A Case Study of Two Compensation Approaches for Community Doula Care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10817. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010817

Gomez AM, Arteaga S, Arcara J, Cuentos A, Armstead M, Mehra R, Logan RG, Jackson AV, Marshall CJ. “My 9 to 5 Job Is Birth Work”: A Case Study of Two Compensation Approaches for Community Doula Care. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(20):10817. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010817

Chicago/Turabian StyleGomez, Anu Manchikanti, Stephanie Arteaga, Jennet Arcara, Alli Cuentos, Marna Armstead, Renee Mehra, Rachel G. Logan, Andrea V. Jackson, and Cassondra J. Marshall. 2021. "“My 9 to 5 Job Is Birth Work”: A Case Study of Two Compensation Approaches for Community Doula Care" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 20: 10817. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010817

APA StyleGomez, A. M., Arteaga, S., Arcara, J., Cuentos, A., Armstead, M., Mehra, R., Logan, R. G., Jackson, A. V., & Marshall, C. J. (2021). “My 9 to 5 Job Is Birth Work”: A Case Study of Two Compensation Approaches for Community Doula Care. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(20), 10817. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010817