Investigating the Feasibility of a Restaurant Delivery Service to Improve Food Security among College Students Experiencing Marginal Food Security, a Head-to-Head Trial with Grocery Store Gift Cards

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

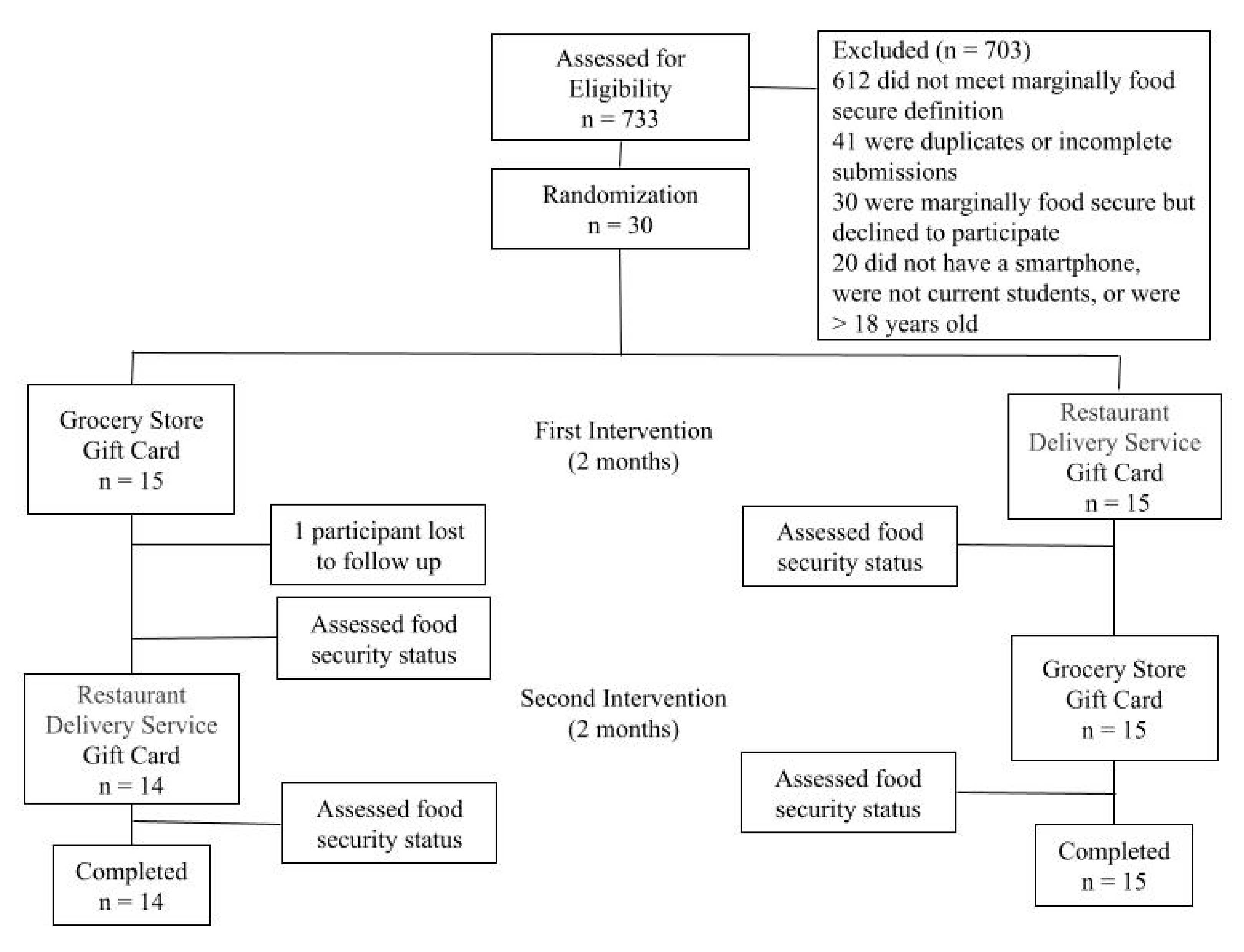

2.1. Participants and Design

2.2. Measurement

2.3. Quantitative Analysis

2.4. Qualitative Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Semi-Structured Interview Questionnaire

- With which benefit do you think you were able to buy more food with and why?

- Was there ever a time you wanted to purchase food but were unable to because no stores were open on Grubhub? Can you say a little bit about that?

- Was this your first time using Grubhub?

- Was there ever a time you wanted to purchase food but there was a challenge in getting to a grocery store, or the grocery store of your choice? Can you say a little bit about that?

- Did you have challenges purchasing healthy food with either method? Can you say a little bit about that?

- For you, what were the 2 biggest benefits of using the Grubhub Gift Card? (I recognize we talked about this earlier, but to get it to 2 key features).

- For you, what were the 2 biggest benefits of using the grocery store gift card? (I recognize we talked about this earlier, but to get it to 2 key features).

- For you, what were the 2 biggest challenges of using the Grubhub Gift Card? (I recognize we talked about this earlier, but to get it to 2 key features).

- For you, what were the 2 biggest challenges of using the grocery store gift card? (I recognize we talked about this earlier, but to get it to 2 key features).

- Do you think the timing in which you received the benefits mattered in terms of what you bought? How would it have been different for you if you received the other type of benefit first, (typically in the summer)?

- Which method did you prefer and why?

- Which method would you prefer for your final month and why?

- For whichever benefit you prefer, would you be willing to receive $10 less in benefits to receive those benefits through your preferred method? Why?

- Is there anything about your life circumstances that affected how you felt about the two methods? If so, how? Ex. Not having a car, having kids, disability etc.

- If you had any stress about running out of food, was either method more helpful, why

- Which method do you think is better for improving food security status of college students and why?

- Any other thoughts regarding the two methods?

- If you were to provide food benefits to students, how would you do so? Meaning, if you had a chunk of money and you were told to assist students with their food situations, how might you do this?

References

- United States Department of Agriculture Measurement. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/measurement.aspx (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Crutchfield, R.; Maguire, J. Study of Student Basic Needs; California State University: Long Beach, CA, USA, 2018; p. 53. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Agriculture Definitions of Food Security. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/definitions-of-food-security.aspx (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Cook, J.T.; Black, M.; Chilton, M.; Cutts, D.; Ettinger de Cuba, S.; Heeren, T.C.; Rose-Jacobs, R.; Sandel, M.; Casey, P.H.; Coleman, S.; et al. Are food insecurity’s health impacts underestimated in the U.S. population? marginal food security also predicts adverse health outcomes in young U.S. children and mothers. Adv. Nutr. 2013, 4, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gamba, R.J.; Schmeltz, M.T.; Ortiz, N.; Engelman, A.; Lam, J.; Ampil, A.; Pritchard, M.M.; Santillan, J.K.A.; Rivera, E.S.; Wood, L.M.; et al. ‘Spending all this time stressing and worrying and calculating’: Marginal food security and student life at a Diverse Urban University. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 2788–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, C.W.; Wolfson, J.A.; Lahne, J.; Barry, M.R.; Kasper, N.; Cohen, A.J. Associations between food security status and diet-related outcomes among students at a large, public midwestern university. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 119, 1623–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne-Sturges, D.C.; Tjaden, A.; Caldeira, K.M.; Vincent, K.B.; Arria, A.M. Student hunger on campus: Food insecurity among college students and implications for academic institutions. Am. J. Health Promot. 2018, 32, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soldavini, J.; Berner, M. The importance of precision: Differences in characteristics associated with levels of food security among college students. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 1473–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabli, J.; Ohls, J. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program participation is associated with an increase in household food security in a national evaluation. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allison, T. Rethinking SNAP Benefits for College Students; Young Invincibles: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- United States Government Accountability Office. Better Information Could Help Eligible College Students Access Federal Food Assistance Benefits; United States Government Accountability Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Granville, P. Congress Made 3 Million College Students Newly Eligible for SNAP Food Aid. Here’s What Must Come Next. Available online: https://tcf.org/content/commentary/congress-made-3-million-college-students-newly-eligible-snap-food-aid-heres-must-come-next/ (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Freudenberg, N.; Goldrick-Rab, S.; Poppendieck, J. College Students and SNAP: The New Face of Food Insecurity in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 2019, 109, 1652–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Department of Agriculture AskUSDA. Available online: https://ask.usda.gov/s/article/Can-I-buy-food-at-restaurants-with-Supplemental-Nutrition-Assistance-Program-benefits-For-SNAP-Clien (accessed on 23 August 2021).

- California EBT Project Office. California Restaurant Meals Program. Available online: https://www.ebtproject.ca.gov/Clients/calfreshrmp.html (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Dumars, A. Use of Electronic Apps and Media for Food-Related Tasks among College Students 2017; Southeast Missouri State University: Cape Girardeau, MO, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C. Food Delivery Apps Serve as Rising Competitor for University Dining Halls. Northwest. Bus. Rev. 2018. Available online: https://northwesternbusinessreview.org/food-delivery-apps-serve-as-rising-competitor-for-university-dining-halls-efc8a28e395f (accessed on 24 August 2021).

- Gaines, A.; Robb, C.A.; Knol, L.L.; Sickler, S. Examining the role of financial factors, resources and skills in predicting food security status among college students. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, L. Understanding food insecurity among college students: Experience, motivation, and local solutions. Ann. Anthropol. Pract. 2017, 41, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botts, J.; Mello, F. College Students, Seniors and Immigrants Miss Out on Food Stamps. Here’s Why. CalMatters 2020. Available online: https://calmatters.org/projects/california-food-stamp-gap-seniors-students-immigrants-calfresh/ (accessed on 24 August 2021).

- Economic Research Service U.S. Adult Food Security Survey Module: Three-Stage Design, with Screeners. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/media/8279/ad2012.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2021).

- Ellison, B.; Bruening, M.; Hruschka, D.J.; Nikolaus, C.J.; van Woerden, I.; Rabbitt, M.P.; Nickols-Richardson, S.M. Viewpoint: Food insecurity among college students: A case for consistent and comparable measurement. Food Policy 2021, 101, 102031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazmi, A.; Martinez, S.; Byrd, A.; Robinson, D.; Bianco, S.; Maguire, J.; Crutchfield, R.M.; Condron, K.; Ritchie, L. A systematic review of food insecurity among US students in higher education. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2019, 14, 725–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 160940691773384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paola, J.; DeBate, R. Employing Evaluation Research to Inform Campus Food Pantry Policy. Health Behav. Policy Rev. 2018, 5, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.; Gould, M.K.; Mount, M.; Gannon, A.; Fox, A. Evaluation of Marshall University Smarter Food Pantry. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2019, 51, S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, P.; Mallick, S.; Flies, E.; Jones, P.; Pearson, S.; Koolhof, I.; Byrne, J.; Kendal, D. Trust, Connection and Equity: Can Understanding Context Help to Establish Successful Campus Community Gardens? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swipe Out Hunger Swipe Out Hunger. Available online: https://www.swipehunger.org/ (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- University of California, Merced No Food Left Behind. Available online: https://sustainability.ucmerced.edu/initiatives/food/no-food-left-behind (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Gleason, P.M.; Kleinman, R.; Chojnacki, G.J.; Briefel, R.R.; Forrestal, S.G. Measuring the Effects of a Demonstration to Reduce Childhood Food Insecurity: A Randomized Controlled Trial of the Nevada Healthy, Hunger Free Kids Project. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, S22–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chojnacki, G.J.; Gothro, A.G.; Gleason, P.M.; Forrestal, S.G. A Randomized Controlled Trial Measuring Effects of Extra Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Benefits on Child Food Security in Low-Income Families in Rural Kentucky. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, S9–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briefel, R.R.; Chojnacki, G.J.; Gabor, V.; Forrestal, S.G.; Kleinman, R.; Cabili, C.; Gleason, P.M. A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial of a Home-Delivered Food Box on Food Security in Chickasaw Nation. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, S46–S58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, A.M.; Klerman, J.A.; Briefel, R.; Rowe, G.; Gordon, A.R.; Logan, C.W.; Wolf, A.; Bell, S.H. A Summer Nutrition Benefit Pilot Program and Low-income Children’s Food Security. Pediatrics 2018, 141, e20171657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Characteristics | Selection | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | 18–24 | 22 (75.86) |

| 25–29 | 4 (13.79) | |

| ≥30 | 2 (6.90) | |

| Missing | 1 (3.45) | |

| Gender | Female | 22 (75.86) |

| Male | 6 (20.70) | |

| Missing | 1 (3.45) | |

| Race/Ethnicity 1 | Asian | 22 (75.86) |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 6 (20.70) | |

| White/Caucasian | 1 (3.45) | |

| Filipinx/Pacific Islander | 22 (75.86) | |

| African American/Black | 6 (20.70) | |

| Indian | 1 (3.45) | |

| Middle Eastern | 22 (75.86) | |

| Missing | 6 (20.70) | |

| Transfer vs. Native Students | Transfer | 16 (55.17) |

| Native | 12 (41.40) | |

| Missing | 1 (3.45) | |

| Graduate vs. Undergraduate Students | Undergraduate | 23 (79.31) |

| Graduate | 5 (17.24) | |

| Missing | 1 (3.45) | |

| Hours Worked per Week | 0 | 5 (17.24) |

| 1–≤10 | 4 (13.79) | |

| 11–≤20 | 8 (27.59) | |

| 21–≤30 | 5 (17.24) | |

| >30 | 4 (13.79) | |

| Seasonal | 1 (3.45) | |

| Missing | 2 (6.90) | |

| Financial Support from Parents/Caregivers/Others | Receiving Support | 18 (62.07) |

| Not Receiving Support | 10 (34.48) | |

| Missing | 1 (3.45) | |

| Eligibility to Participate in SNAP 2 | Unsure of Eligibility | 15 (51.72) |

| Eligible | 6 (20.70) | |

| Not Eligible | 8 (27.59) | |

| Adequate Food Storage | Yes | 22 (75.86) |

| No | 8 (27.59) | |

| Adequate Cooking Equipment | Yes | 27 (93.10) |

| No | 1 (3.45) | |

| Missing | 2 (6.90) |

| Issue | Selection | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Selected Grocery Store Gift Card for Final (5th) Month? | Yes | 26 (89.66) |

| No | 3 (10.34) | |

| Used All Benefits 1 | Yes | 14 (48.28) |

| No | 15 (51.72) | |

| Received New Food Assistance in the Last 60 Days | Yes | 4 (13.79) |

| No | 24 (82.76) | |

| Missing | 1 (3.33) | |

| First Time Using Grubhub | Yes | 22 (73.33) |

| No | 7 (23.33) | |

| Missing | 1 (3.33) | |

| Timing of Benefits Mattered 2 | Yes | 16 (53.33) |

| No | 12 (40.00) | |

| Unclear | 1 (3.33) | |

| Shared Benefits | Shared Grocery Store Benefits | 3 (10.00) |

| Shared Grubhub Benefits | 4 (13.33) | |

| Shared Grocery Store and Grubhub Benefits | 3 (10.00) 3 | |

| Did Not Share Either Benefit | 25 (83.33) |

| Categories | Themes | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Grocery Store Benefit Themes | Greater Purchasing Power | “You got way more food, and then you can kind of tailor your meal to what you want, same as you know going grocery shopping so you don’t have to order off so and so’s menu and then be like, well I’m gonna get this because this is what I like and then take off x, y, z or add x, y, z for more money. It was just kind of like, well I can already make that and just buy out things but not only I can make it and buy all the things but I’ll have that same meal multiple times instead of just once so you got more multiple meals for probably like the same amount of money.” “With groceries. I felt like with the grocery you can buy a lot of food and it can even last for weeks.” |

| Greater Options and More Healthy Options | “Of course, at a grocery store, you get more, and it’s healthier, you could really pick what you want.” “With the grocery store, I liked it more because it was more customizable in the sense that you really get to pick what you want, you could span out breakfast, lunch, dinner, it goes farther, and of course it was healthier and allowed me to kind of figure out what I wanted to eat for that week instead of just picking whatever was on (restaurant delivery service), because there is no like- not every store in Hayward is on (restaurant delivery service), so you have a very few selected restaurants where you could choose from.” | |

| Restaurant Delivery Service Benefit Themes | Not Having to Cook | “Two biggest benefits is that it’s very not as time-consuming as like you cooking and like, for example, a student needs time to study and do academics in which I could just open up my laptop, order it, and keep studying while I wait for my food to get there and then just have like a mini-break to eat my food and get back to studying which was really convenient times-wise.” “The fact the food was coming to you was obviously a huge benefit and then you don’t have to spend any time preparing that food. It was just like, alright thanks and you can go eat.” “I didn’t have to cook, I didn’t have to clean my pots and pans.” |

| Convenience of Not Having to Travel | “I liked that it was, like I didn’t have to make food. I kinda just had to put in an order and then I could probably have more time to do homework or something while it was delivered to my door.” “I think the convenience to be able to get a meal without having to necessarily like spend as much effort for going out to grocery shop or going to a restaurant, and being able to spend that time on other things.” | |

| Restaurant Delivery Service Challenges Themes | Pricing/Tipping | “Not a lot of options and expensive.” Interviewer: “Okay, so you say for like GrubHub, you generally sacrificed part of your like health? Or like the healthier option?” RG25: “Yeah. Because it’s just the, okay you want, you’re like you want this one but since it’ll cost you more and then you’ll just like oh, change your mind and then just go to what you can afford.” “Yeah like a service fee or something and then the delivery, and then the delivery, and then the tip for the driver, and like cuz it’s my first time using it so the first time which I kind of feel bad for doing this but the first time it kinda just it automatically keeps doing this where like it calculates how much you spend on food and like how much you have to pay the driver like either 10%, 20%, 40%, and then after that like the website calculates it by itself and it tells you how much you’re supposed to pay and you just like click pay now and that’s it, you know the order has been sent but the second time I kinda started playing around with the website and I actually found like this button where it says that you can like put another tip like another amount of tip and you can like change it to where it automatically sets it up to and then instead of like for example if I paid like $10 for like a plate or something and instead of paying the driver like $3 or $4 or whatever, I would like delete it and put like 50 cents or something so like I would have more money.” |

| Poor Food Quality | “I feel like it’s just temptation of just like you know, it’s a lot of fast food, so, you know obviously there’s a lot like, not a lot of healthy options I guess.” “Um, Let’s see… Well, in the beginning I was searching for healthier options for Grubhub, but then like I said, out of the stores here in the area, I was able to find one store, but the food wasn’t that appetizing.” | |

| Cancelations/ Delays | “Yeah, this was just this one time. But, one thing that was consistent is that they always took forever. That was something, was something that was consistent, yeah.” “Yeah, so there was like twice I tried ordering and they canceled my food order on me, so it was just kind of like—it’s not—I just think it’s the app, if the app was built better, like that was my only complaint, if it was like made better, like to work better, it would have been okay.” |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gamba, R.J.; Wood, L.M.; Ampil, A.; Engelman, A.; Lam, J.; Schmeltz, M.T.; Pritchard, M.M.; Santillan, J.K.A.; Rivera, E.S.; Ortiz, N.; et al. Investigating the Feasibility of a Restaurant Delivery Service to Improve Food Security among College Students Experiencing Marginal Food Security, a Head-to-Head Trial with Grocery Store Gift Cards. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9680. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189680

Gamba RJ, Wood LM, Ampil A, Engelman A, Lam J, Schmeltz MT, Pritchard MM, Santillan JKA, Rivera ES, Ortiz N, et al. Investigating the Feasibility of a Restaurant Delivery Service to Improve Food Security among College Students Experiencing Marginal Food Security, a Head-to-Head Trial with Grocery Store Gift Cards. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(18):9680. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189680

Chicago/Turabian StyleGamba, Ryan J., Lana Mariko Wood, Adianez Ampil, Alina Engelman, Juleen Lam, Michael T. Schmeltz, Maria M. Pritchard, Joshua Kier Adrian Santillan, Esteban S. Rivera, Nancy Ortiz, and et al. 2021. "Investigating the Feasibility of a Restaurant Delivery Service to Improve Food Security among College Students Experiencing Marginal Food Security, a Head-to-Head Trial with Grocery Store Gift Cards" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 18: 9680. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189680

APA StyleGamba, R. J., Wood, L. M., Ampil, A., Engelman, A., Lam, J., Schmeltz, M. T., Pritchard, M. M., Santillan, J. K. A., Rivera, E. S., Ortiz, N., Ingram, D., Cheyne, K., & Taylor, S. (2021). Investigating the Feasibility of a Restaurant Delivery Service to Improve Food Security among College Students Experiencing Marginal Food Security, a Head-to-Head Trial with Grocery Store Gift Cards. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), 9680. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189680