A Participatory Community Diagnosis of a Rural Community from the Perspective of Its Women, Leading to Proposals for Action

Abstract

:1. Introduction

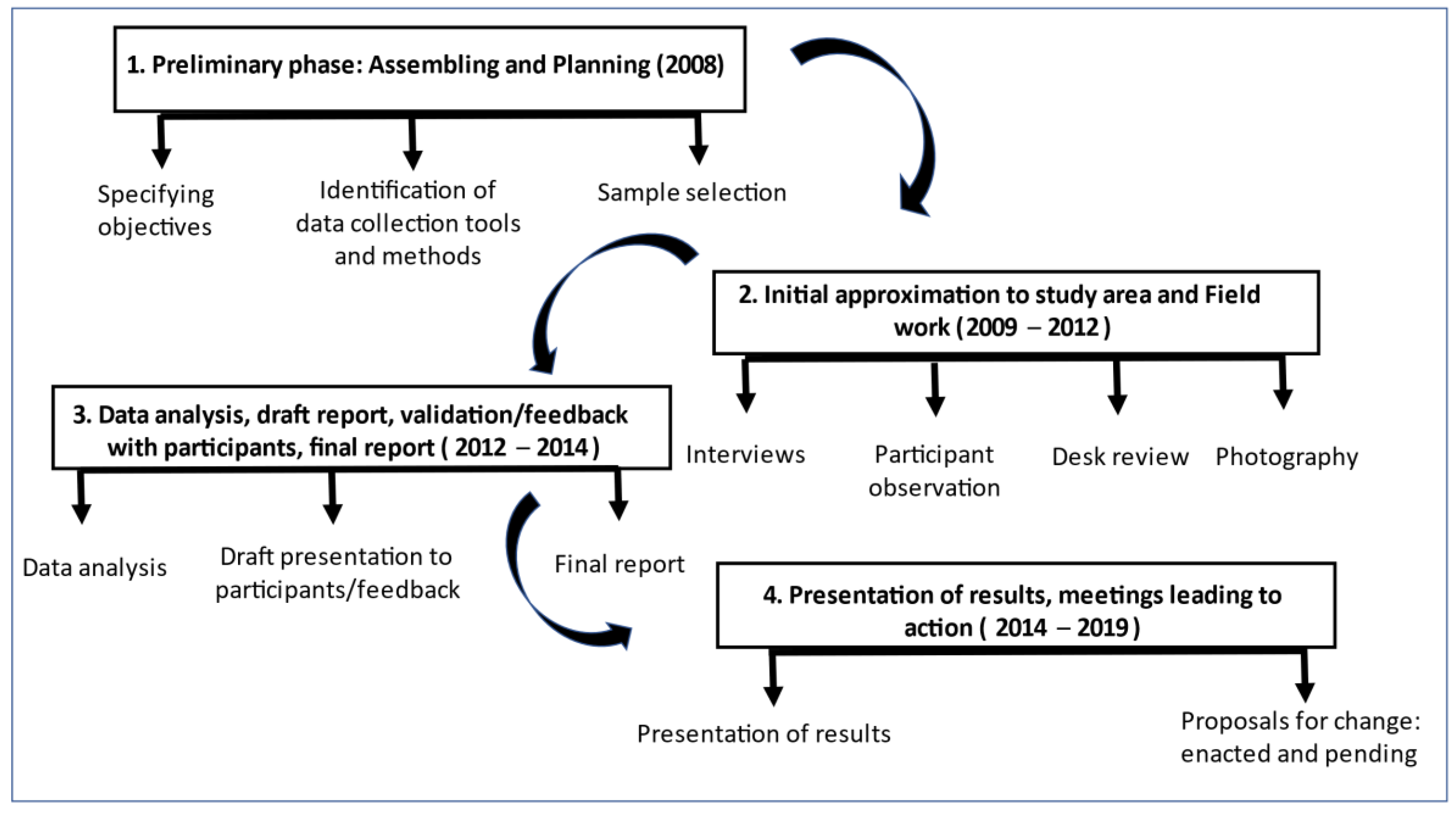

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. The Sample

3.2. Meta-Categories and Thematic Nuclei

3.3. Meta-Categories

3.3.1. Population

3.3.2. From Home to Community Economics

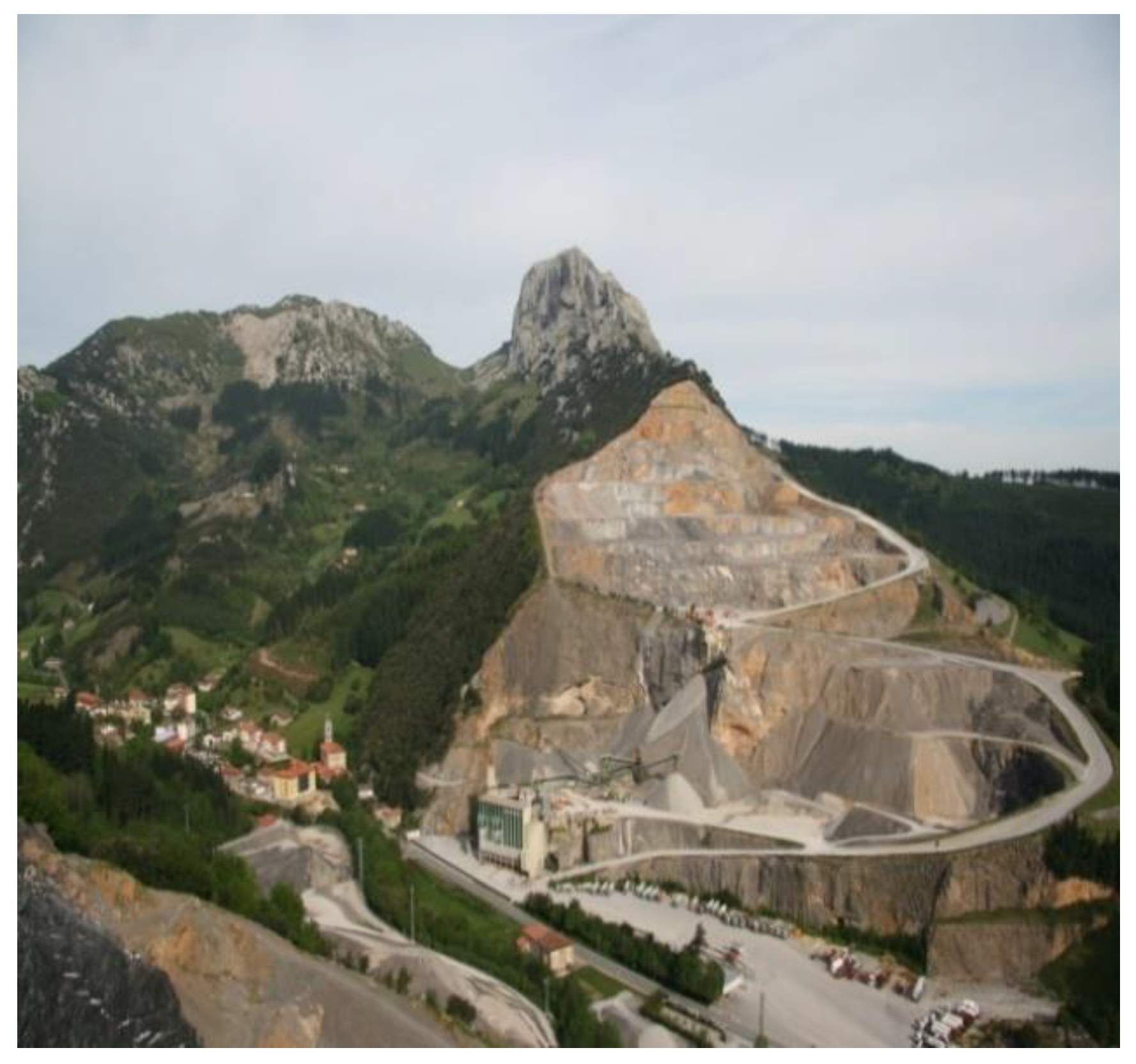

3.3.3. Public and Private Spaces

3.3.4. Habits and Lifestyles

3.3.5. Socializing Process

3.3.6. Health Care Resources

| Meta Categories | Proposals for Change Identified by Participants (After Feedback and Discussion with the Community) | Proposals for Change, Enacted and Pending (*) |

|---|---|---|

| Population |

|

|

| Domestic and community economy |

|

|

| Public and private spaces |

|

|

| Life habits and lifestyle |

|

|

| Socializing process |

|

|

| Health care resources |

|

|

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ramos, E. Diagnóstico de salud de la comunidad, métodos y técnicas. In Enfermería Comunitaria; Darías-Curvo, S., Ed.; DAE (Grupo Paradigma): Madrid, España, 2009; pp. 509–527. [Google Scholar]

- Molewyk, M.; Ayoola, A.; Topp, R.; Landheer, G. Conducting research with community groups. West J. Nurs. Res. 2015, 37, 1323–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mason, D.J. Building healthy communities. Nurs. Outlook 2015, 63, 384–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, F.A.; Goulart, M.J.; Braga, A.M.; Medeiros, C.M.; Rego, D.C.; Vieira, F.G.; Pereira, H.J.; Tavares, H.M.; Loura, M.M. Setting health priorities in a community: A case example. Rev. Saude Publica 2017, 51, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Colell, E.; Sánchez-Ledesma, E.; Novoa Ana, M.; Daban, F.; Fernández, A.; Juárez, O.; Pérez, K. El diagnóstico de salud del programa Barcelona Salut als Barris. Metodología para un proceso participativo. Community health assessment of the programme “Barcelona Health in the Neighbourhoods”. Methodology for a participatory process. Gac. Sanit. 2018, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchioni, M.; Morin, L.M.; Álamo, J. Metodología de la Intervención Comunitaria. Los Procesos Comunitarios. En: Hagamos de Nuestro Barrio Un Lugar Habitable. Manual De Intervención Comunitaria En Barrios; Buades, J., Giménez, C., Eds.; Fundación CeiMigra: Valencia, España, 2013; pp. 58–73. [Google Scholar]

- Benito, A.; Nuin, B.; Sorarrain, Y.; Blanco, M.; Astillero, M.J.; Paskual, A.; Porta, A.; Vergara, I. Guía Metodológica Para el Abordaje de la Salud Desde una Perspectiva Comunitaria; Departamento de Salud, Gobierno Vasco Vitoria-Gasteiz: País Vasco, Spain, 2016; BI-1192-2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tamayo, M.; Besoaín, A.; Rebolledo, J. Determinantes sociales de la salud y discapacidad: Actualizando el modelo de determinación. Gac. Sanit. 2018, 32, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espelt, A.; Continente, X.; Domingo-Salvany, A.; Domínguez-Berjón, M.F.; Fernández-Villa, T.; Monge, S.; Ruiz-Cantero, M.T.; Pérez, G.; Borrel, C. La vigilancia de los determinantes sociales de la salud. Grupo de Determinantes Sociales de la Salud de la Sociedad Española de Epidemiologia. Gac. Sanit. 2016, 30, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Escartin, P.; López, V.; Ruiz-Jimenez, J.L. La participación comunitaria en salud. Comunidad 2015, 17, 16. Available online: http://goo.gl/PkfW2O (accessed on 28 June 2021).

- González-González, J.; Rico-García, G.; Izaguirre-Zapatera, A.M.; De Ángel-Larrinaga, S.; Lor-Martín, M. Mujeres cuidadoras: Intervención comunitaria en mujeres promotoras de salud rural. Med. Gen. Y Fam. 2016, 5, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCormack, C. Planning and evaluating women’s participation in primary health care. Soc. Sci. Med. 1992, 35, 831–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas-Monreal, L.; Cortez-Lugo, M.; Parada-Toro, I.; Pacheco-Magaña, L.E.; Magaña-Valladares, L. Population health diagnosis with an ecohealth approach. Rev. Saude Pública 2015, 49, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Freidin, B.; Ballesteros, M.; Wilner, A. Navigating the public health services: The experiences of women who live in the periphery of Buenos Aires city. Saude Soc. 2019, 28, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, V.C.; Shaoxian, W.; Kunyi, W.; Wentao, Z.; Buchthal, O.; Wong, G.C.; Burris, M.A. Capacity building to improve women’s health in rural China. Soc. Sci. Med. 2001, 52, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, I.; Navarrete, A.; Santos, C. La salud de Ronda, percepciones de su gente: Uso de las técnicas cualitativas para conocer el estado. A Tu Salud Rev. De Educ. Para La Salud 1995, 3, 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Gobierno de Canarias; Consejería de Empleo y Asuntos Sociales; Ayuntamiento de Telde y Grupo Técnico de Coordinación Las Remudas y La Pardilla. Dos Barrios Hablan. Las Remudas y La Pardilla; Tapizca: Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Arenas-Monreal, L.; Cortez-Lugo, M.; Parada-Toro, I.; Pacheco-Magaña, L.; Magaña-Valladares, L. Diagnóstico de salud poblacional con enfoque de ecosalud. Rev. Saúde Pública 2015, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ponce, M.L.; Díaz, B.; Sánchez, B.; Garrido, M.L.; Lara, T.; Del Ángel de León, A.; De la Rosa, A. Diagnóstico comunitario de la situación de salud de una población urbano marginada. Vertientes. Rev. Espec. En Cienc. De La Salud 2005, 8, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ashton, J.; Grey, P.; Barnard, K. Healthy cities-WHO’s new public health initiative. Health Promot. Int. 1986, 1, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaner, I.; Fernandes, S.; Badia, M.; Martinez, D.; Aranda, B.; Ruiz, F.J.; Delgado, J.; Gonzalez, F. ‘El Carmel’ community-orientation experience. Int. J. Integr. Care 2016, 16, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sánchez-Ledesma, E.; Pérez, A.; Vázquez, N.; García-Subirats, I.; Fernández, A.; Novoa, A.M.; Davan, F. La priorización comunitaria en el programa Barcelona Salut als Barris. Grupo de Trabajo de Priorización. Gac. Sanit. 2018, 32, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valls-Llobet, C. Salud comunitaria con perspectiva de género. Comunidad 2008, 10, 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Spiers, J.; Morse, J.M.; Olson, K. Verification Strategies for Establishing Reliability and Validity in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2002, 1, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, K. Ethnographic Methods; Routledge: Abingdon, England, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Driessnack, M.; Sousa, V.; Mendes, I.A. An overview of research designs relevant to nursing: Qualitative designs. Rev. Latino-Am. Enfermagem. 2007, 15, 684–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Strauss, A.L.; Corbin, J.M. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, H.R. Research Methods in Anthropology. Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, 6th ed.; Roberts, N.E., Ed.; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gállego-Diéguez, J.; Aliaga-Traín, P.; Benedé-Azagra, C.B.; Bueno-Franco, M.; Ferrer-Gracia, E.; Ipiéns-Sarrate, J.R.; Muñoz-Nadal, P.; Plumed-Parrilla, M.; Vilches-Urrutia, B. Las redes de experiencias de salud comunitaria como sistema de información en promoción de la salud: La trayectoria en Aragón. Gac. Sanit. 2016, 30, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmer, C.; Griffiths, F.; Dunn, J. A review of the issues and challenges involved in using participant produced photographs in nursing research. J. Adv. Nurs. 2015, 71, 1726–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Routledge-Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lancharro-Tavero, I.; Gil-García, E.; Macías-Seda, J.; Romero-Serrano, R.; Calvo-Cabrera, I.M.; Arroyo-Rodríguez, A. The gender perspective in the opinions and discourse of women about caregiving. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2018, 52, e03370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item. Checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Calderón, C. Quality criteria in qualitative health research: Notes for a necessary debate. Rev. Esp. Salud. Pública 2002. Available online: http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1135-57272002000500009&lng=en&tlng=en (accessed on 28 June 2021).

- Sobrino, K.; Hernán, M.; Cofiño, R. ¿De qué hablamos cuando hablamos de «salud comunitaria»? Gac. Sanit. 2018, 32, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-García, M.; Ponte-Mittelbrun, C.; Sánchez-Bayle, M. Participación social y orientación comunitaria en los servicios de salud. Gac. Sanit. 2006, 20, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Jakarta Declaration on Health Promotion in the 21st Century. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Health Promotion, Jakarta, Indonesia, 21–25 July 1997; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1988. Available online: http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/jakarta/en/hpr_jakarta_declaration_sp.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2021).

- World Health Organization. Declaration of Mexico towards greater equity. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Health Promotion towards greater equity, Mexico City, Mexico, 5–9 June 2000; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. Available online: https://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/mexico/en/hpr_mexico_report_en.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 28 June 2021).

- Gobierno Vasco. Osasuna, Pertsonen Eskubidea, Guztion Ardura. Políticas de Salud para Euskadi 2013–2020; Gobierno Vasco Departamento de Salud: Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain, 2013. Available online: http://goo.gl/8sDxR0 (accessed on 28 June 2021).

- Departamento de Salud; Sede Web; Gobierno Vasco. Plan de Atención Integrada en Euskadi. 2016. Available online: http://goo.gl/1bfLGI (accessed on 28 June 2021).

- Saenz del Castillo, A. De las Hermandades a la Seguridad Social. Estudios sobre previsión social en el País Vasco, siglos XIX–XXI. Hist. Contemp. 2019, 60, 733–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, S.; Soler, M.; Miller, F.; Montaner, I.; Pérez, M.J.; Ramos, M. Variabilidad en la implantación de las actividades comunitarias de promoción de la salud en España. An. Sist. Sanit. Navar. 2014, 37, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Leon, M.; Jimenez, M.; Vidal, N.; Bermudez, K.; De Vos, P. The Role of Social Movements in Strengthening Health Systems: The Experience of the National Health Forum in El Salvador (2009–2018). Int. J. Health Serv. 2020, 50, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cofiño, R.; Aviñó, D.; Benedé, C.; Botello, B.; Cubillo, J.; Morgan, A.; Paredes-Carbonell, J.J.; Hernán, M. Promoción de la salud basada en activos: ¿cómo trabajar con esta perspectiva en intervenciones locales? Gac. Sanit. 2016, 30, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, S.B.; Pascual, C.A.; Chickering, K.L. Empowerment of women for health promotion: A meta-analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 1999, 49, 1431–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Casado, L.; Paredes-Carbonell, J.J.; López-Sánchez, P.; Morgan, A. Mapa de activos para la salud y la convivencia: Propuestas de acción desde la intersectorialidad. Index. Enferm. 2017. Available online: http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1132-12962017000200013&lng=es (accessed on 28 June 2021).

| Structure of the Female Population in Mañaria, by Age Group | Sample Selected for Interview, by Age Group and Zone within the Community (2008) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neighborhood | ||||||||||

| Age (years) | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | Sample | Urban center | Aldebaraieta | Aldebarrena | Aldegoiena | Arrueta | Urkuleta |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | 15 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||

| 10–24 | 31 (14%) | 34 (14%) | 31 (13%) | 2 (10%) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 25–54 | 102 (46%) | 107 (46%) | 109 (46) | 12 (57%) | 8 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 55–69 | 41 (18%) | 45 (19%) | 48 (20%) | 5 (24%) | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| ≥70 | 37 (17%) | 34 (14%) | 34 (14%) | 2 (10%) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 211 | 220 | 222 | 21 | 15 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| IN-DEPTH (General and Open-Ended Questions) | SEMI-STRUCTURED (Topics) |

|---|---|

| What do you think about the community’s health in Mañaria? | DEMOGRAPHIC STRUCTURE |

| What aspects may be involved to make this community more healthy or less healthy? | ECONOMIC STRUCTURE Business and public establishments Industry |

| What do you like about this community? | URBAN STRUCTURE Solid waste Cleanliness Urban design Urban furniture Housing Green areas Other urban aspects |

| What things do you miss? | SOCIAL SYSTEM Resources and community services Socializing process |

| What things do you think should improve? | HEALTH CARE SYSTEM Formal health care system Informal health care system |

| Meta-Categories | Thematic Nuclei | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Housing | |

| Work | ||

| Environment | ||

| Domestic and community economy | Non-remunerated work | |

| Remunerated employment | ||

| Community participatory work | ||

| Public and private spaces | Public space: | Private space: |

| Quarries | Comfort | |

| Main highway | Accessibility | |

| Architectonic barriers | Tranquility | |

| Mobility | Overcrowding | |

| Esthetics | Building maintenance | |

| Residues | Coexisting with neighbors | |

| Public safety | Private safety | |

| Life habits and lifestyle | Food | |

| Alcohol | ||

| Tobacco | ||

| Rest/sleep | ||

| Leisure and free time | ||

| Socializing process | Formal scenarios: | Informal scenarios: |

| Old school | Church | |

| Childcare | Fronton | |

| Cultural Center | ||

| Central square | ||

| Retiree House | ||

| Townhall spaces | ||

| Health care resources | Care and informal caregivers | Care and formal caregivers: doctor’s office |

| Women, main providers | Material resources | |

| Family | Professional resources | |

| Neighbors | Services offered | |

| Social network | House care | |

| Care | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alberdi-Erice, M.J.; Martinez, H.; Rayón-Valpuesta, E. A Participatory Community Diagnosis of a Rural Community from the Perspective of Its Women, Leading to Proposals for Action. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9661. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189661

Alberdi-Erice MJ, Martinez H, Rayón-Valpuesta E. A Participatory Community Diagnosis of a Rural Community from the Perspective of Its Women, Leading to Proposals for Action. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(18):9661. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189661

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlberdi-Erice, Maria Jose, Homero Martinez, and Esperanza Rayón-Valpuesta. 2021. "A Participatory Community Diagnosis of a Rural Community from the Perspective of Its Women, Leading to Proposals for Action" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 18: 9661. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189661

APA StyleAlberdi-Erice, M. J., Martinez, H., & Rayón-Valpuesta, E. (2021). A Participatory Community Diagnosis of a Rural Community from the Perspective of Its Women, Leading to Proposals for Action. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), 9661. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189661