A Scoping Review of Interventions for the Treatment of Eco-Anxiety

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- What is known from the existing published literature about interventions for the individual and group treatment of eco-anxiety?

- 2.

- What published literature is available from different psychological approaches/perspectives on interventions for the treatment of eco-anxiety?

- 3.

- How do different psychological approaches differ or concur on the interventions they propose for the treatment of eco-anxiety?

- 4.

- What published literature exists proving the efficacy of any of these interventions?

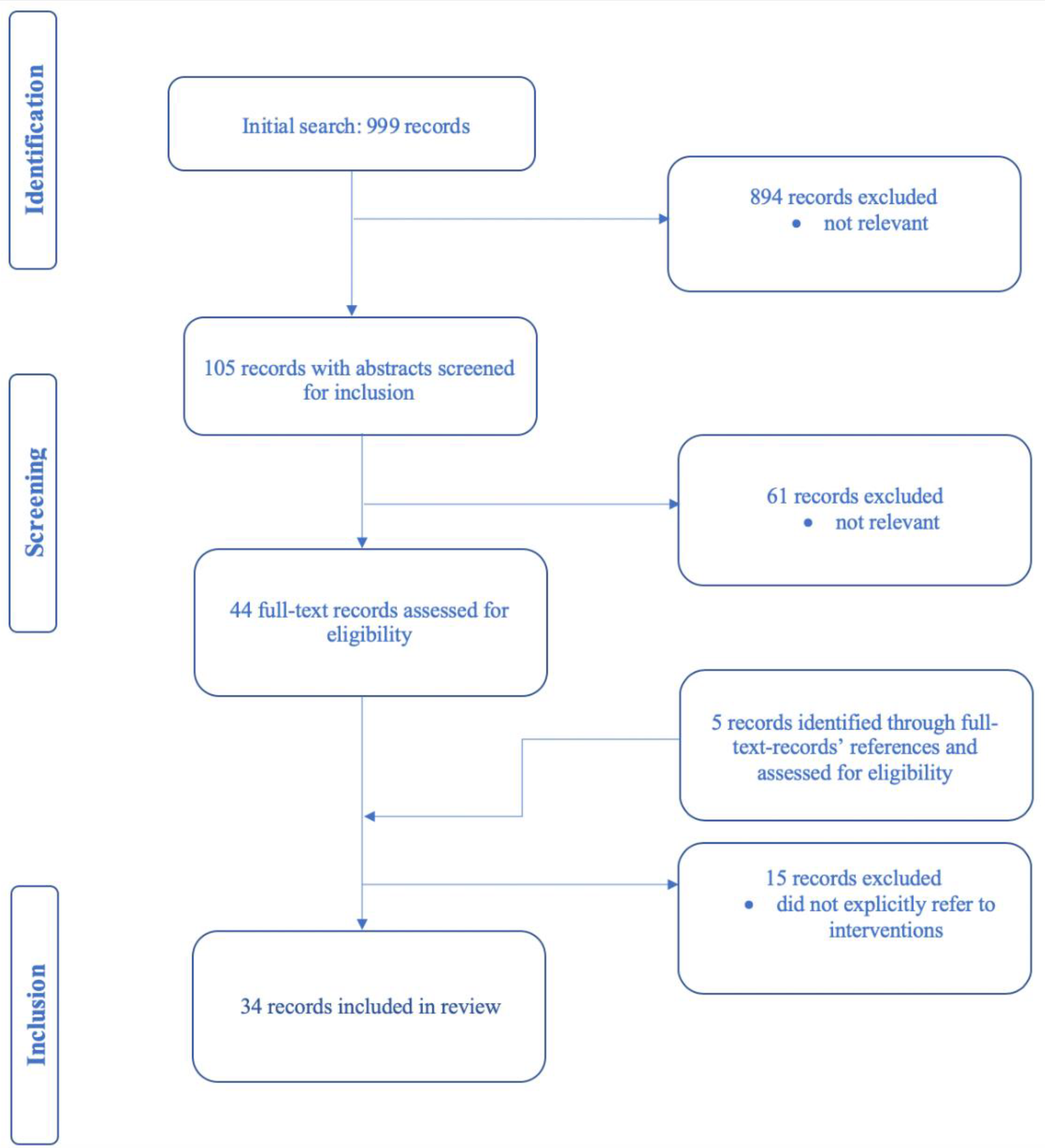

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Thematic Analysis

3.1.1. Theme One: Fostering Clients’ Inner Resilience (n = 31 Papers)

3.1.2. Theme Two: Helping Clients Find Social Connection and Emotional Support by Joining Groups (n = 21 Papers)

3.1.3. Theme Three: Encouraging Clients to Take Action (n = 15 Papers)

3.1.4. Theme Four: Practitioner’s Inner Work and Education (n = 13 Papers)

3.1.5. Theme Five: Connecting Clients with Nature (n = 9 Papers)

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Search Terms

- Eco-anxiety; Eco anxiety; Ecoanxiety; Ecoanxiety treatment; Eco-anxiety treatment

- Eco anxiety treatment; Eco anxiety intervention; Ecological anxiety treatment

- Environmental anxiety; Eco angst; Climate change distress; Climate distress treatment; Climate distress intervention; Climate change fear

References

- Nurse, J.; Basher, D.; Bone, A.; Bird, W. An ecological approach to promoting population mental health and well-being-a response to the challenge of climate change. Perspect. Public Health 2010, 130, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of California, Davis. Climate Change Terms and Definitions. Available online: https://climatechange.ucdavis.edu/science/climate-change-definitions/ (accessed on 5 April 2020).

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change IPCC. Annex I: Glossary Global Warming of 1.5 °C. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/ (accessed on 3 March 2020).

- Jackman, K.P.; Uznanski, W.; McDermott-Levy, R.; Cook, C. Climate change: Preparing the nurses of the future. Dean Notes 2018, 39, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Fritze, J.; Blashki, G.; Burke, S.; Wiseman, J. Hope, despair and transformation: Climate change and the promotion of mental health and wellbeing. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2008, 2, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Watts, N.; Adger, W.N.; Agnolucci, P.; Blackstock, J.; Byass, P.; Cai, W.; Chaytor, S.; Colbourn, T.; Collins, M.; Cooper, A.; et al. Health and climate change: Policy responses to protect public health. Lancet 2015, 386, 1861–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, P. Eco-anxiety, tragedy, and hope: Psychological and spiritual dimensions of climate change. Zygon 2018, 53, 545–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usher, K.; Durkin, J.; Bhullar, N. Eco-anxiety: How thinking about climate change-related environmental decline is affecting our mental health. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 28, 1233–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Calls on Countries to Protect Health from Climate Change. Available online: https://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2015/climate-change/en/ (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- Davenport, L. A new path: The role of systemic therapists in an era of environmental crisis. Fam. Ther. Mag. July-August 2019, 13–16. Available online: https://lesliedavenport.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/The-Role-of-Systemic-Therapists-in-Environmental-Crisis.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Ward, M. Climate Anxiety Is Real, and Young People Are Feeling It. The Sydney Morning Herald. Available online: https://www.smh.com.au/lifestyle/health-and-wellness/climate-anxiety-is-real-and-young-people-are-feeling-it-20190918-p52soj.html (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- Hayes, K.; Blashki, G.; Wiseman, J.; Burke, S.; Reifels, L. Climate change and mental health: Risks, impacts and priority actions. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2018, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikhala, P. Climate Anxiety; MIELI Mental Health Finland: Helsinki, Finland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Castelloe, M.S. Coming to Terms with Ecoanxiety. Psychology Today. Available online: https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/the-me-in-we/201801/coming-terms-ecoanxiety (accessed on 29 March 2020).

- Clayton, S.; Manning, C.M.; Krygsman, K.; Speiser, M. Mental Health and Our Changing Climate: Impacts, Implications, and Guidance; American Psychological Association, and ecoAmerica: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; Available online: https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2017/03/mental-health-climate.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2020).

- Dockett, L. The rise of eco-anxiety. Psychother. Netw. Mag. 2019, 43, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, G.; Sartore, G.-M.; Connor, L.; Higginbotham, N.; Freeman, S.; Kelly, B.; Stain, H.; Tonna, A.; Pollard, G. Solastalgia: The distress caused by environmental change. Australas. Psychiatry 2007, 15, S95–S98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gritters, J. What Is Eco-Anxiety? Available online: https://www.rei.com/blog/news/what-is-eco-anxiety (accessed on 23 May 2020).

- Moser, S.C. More bad news: The risk of neglecting emotional responses to climate change information. In Creating a Climate for Change: Communicating Climate Change and Facilitating Social Change; Moser, S.C., Dilling, L., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; pp. 64–80. [Google Scholar]

- Moser, S.C. Navigating the political and emotional terrain of adaptation: Community engagement when climate change comes home. In Successful Adaptation to Climate Change: Linking Science and Policy in a Rapidly Changing World; Moser, S.C., Boykoff, M.T., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 289–305. [Google Scholar]

- Coyle, K.; Van Susteren, L. The Psychological Effects of Global Warming; National Wildlife Federation: Reston, VA, USA, 2012; Available online: https://nwf.org/~/media/PDFs/Global-Warming/Reports/Psych_effects_Climate_Change_Ex_Sum_3_23.ashxncbi (accessed on 2 April 2020).

- Kerecman Myers, D. Climate Change and Mental Health: Q&A with Lise van Susteren, MD. Global Health Now. Available online: https://www.globalhealthnow.org/2017-03/climate-change-and-mental-health-qa-lise-van-susteren-md (accessed on 13 June 2020).

- Kaplan, E.A. Is climate-related pre-traumatic stress syndrome a real condition? Am. Imago 2020, 77, 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugent, C. Terrified of Climate Change? You Might Have Eco-Anxiety. Available online: https://time.com/5735388/climate-change-eco-anxiety/ (accessed on 3 April 2020).

- Buzzell, L. Asking different questions: Therapy for the human animal. In Eco-Therapy: Healing with Nature in Mind; Buzzell, L., Chalquist, C., Eds.; Sierra Club Books: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Seaman, E.B. Climate Change on the Therapist’s Couch: How Mental Health Clinicians Receive and Respond to Indirect Psychological Impacts of Climate Change in the Therapeutic Setting. Master’s Thesis, Smith College for Social Work, Northampton, MA, USA, 2016. Available online: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/theses/1736 (accessed on 22 February 2020).

- Ashcroft, R.; Silveira, J.; Rush, B.; McKenzie, K. Incentives and disincentives for the treatment of depression and anxiety: A scoping review. Can. J. Psychiatry 2014, 59, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Randall, R. A new climate for psychotherapy? Psychother. Pol. Int. 2005, 3, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokols, D.; Misra, S.; Runnerstrom, M.; Hipp, J.A. Psychology in an age of ecological crisis: From personal angst to collective action. Am. Psychol. 2009, 64, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Randall, R. Loss and climate change: The cost of parallel narratives. Ecopsychology 2009, 1, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, T.J.; Clayton, S. The psychological impacts of global climate change. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kiehl, J.T. A Jungian perspective on global warming. Ecopsychology 2012, 4, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J. What have we done to Mother Earth? Psychodynamic thinking applied to our current world crisis. Psychodyn. Pract. 2013, 19, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasbach, P.H. Therapy in the face of climate change. Ecopsychology 2015, 7, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koger, S.M. A Burgeoning ecopsychological recovery movement. Ecopsychology 2015, 7, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, S. How Do People Cope with Feelings about Climate Change so that They Stay Engaged and Take Action? Available online: https://www.isthishowyoufeel.com/blog/how-do-people-cope-with-feelings-about-climate-change-so-that-they-stay-engaged-and-take-action (accessed on 24 March 2020).

- Lewis, J. In the room with climate anxiety: Part 1. Psychiatric Times 2018, 35, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Ojala, M. Eco-anxiety. RSA J. 2018, 4, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, S. Psychology and climate change. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, R992–R995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haseley, D. Climate change: Clinical considerations. Int. J. Appl. Psychoanal. Stud. 2019, 16, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarchet, P. Stressed about the climate? New Scientist. 2019, 244, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J. In the room with climate anxiety: Part 2. Psychiatric Times 2019, 36, 23–24. [Google Scholar]

- Conyer, M. Climate justice and mental health–think globally, panic internally, act locally. Psychother. Counsell. Today 2019, 1, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo, J.C. I just see nature collapsing around me. Therapy Today 2019, 30, 38. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Conservation Foundation; The Climate Reality Project Australia; Australian Psychological Society; Psychology for a Safe Climate. Coping with Climate Distress. Available online: https://www.psychology.org.au/getmedia/cf076d33-4470-415d-8acc-75f375adf2f3/coping_with_climate_change.pdf.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2020).

- Good Grief Network. 10 Steps to Personal Resilience in a Chaotic Climate. Available online: https://www.goodgriefnetwork.org/archive/good-grief-network-10-step-program/ (accessed on 16 May 2020).

- Randall, R. Climate Journeys: From Anxiety to Action. Available online: https://mieli.fi/sites/default/files/inline/materiaalit/climate_journeys_from_anxiety_to_action_rosemary_randall.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2020).

- Buchs, M.; Hinton, E.; Smith, G. ‘It helped me sort of face the end of the world’: The role of emotions for third sector climate change engagement initiatives. Environ. Values 2015, 24, 621–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kelly, A. Ecoanxiety at University: Student Experiences and Academic Perspectives on Cultivating Healthy Emotional Responses to the Climate Crisis. Available online: http://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2642 (accessed on 19 March 2020).

- Shaffer, D.K. Ecophobia: Keeping hope afloat. Alive Can. Nat. Health Wellness Mag. 2017, 421, 109–113. [Google Scholar]

- Bednarek, S. Is there a therapy for climate-change anxiety? Ther. Today 2019, 30, 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, S. Climate change and psyche: Conversations with and through dreams. Int. J. Mult. Res. Approch. 2013, 7, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C.W. Re-envisioning hope: Anthropogenic climate change, learned ignorance, and religious naturalism. Zygon 2018, 53, 570–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelsey, E. Propagating collective hope in the midst of environmental doom and gloom. Can. J. Environ. Educ. 2016, 21, 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, A.E. Individual psychology and environmental psychology. J. Ind. Psychol. 2007, 63, 67–85. [Google Scholar]

| Main Themes | N * | Sub Themes | Sub-Sub Themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fostering clients’ inner resilience. | 31 | Cognitive interventions. | Shifting from catastrophizing towards a less black-and-white picture. |

| Meaning-focused and existential interventions. | Discussing and relativizing the social and systemic dimensions of climate change. | ||

| Fostering optimism and hope. | |||

| Emotion-focused interventions. | Grief-focused interventions. | ||

| Differentiating between clients’ distress related to their history and distress related to eco-anxiety. | |||

| Self-care interventions. | |||

| Interventions connecting clients with their lyrical self. | Interventions focused on creative expression and the arts. | ||

| Interventions focused on dreams. | |||

| Helping clients find social connection and emotional support by joining groups. | 21 | Joining established groups and organizations. | |

| Group rituals. | |||

| Encouraging clients to take action. | 15 | Individual action. Collective action | |

| Practitioner’s inner work and education. | 13 | Grief awareness. | |

| Connecting clients with nature | 9 |

| Author, Date | Approach | Themes Identified |

|---|---|---|

| Conyer [45] | Counselling, narrative therapy | Fostering clients’ inner resilience: meaning-focused/existential interventions—fostering optimism and hope; interventions connecting clients with their lyrical self—interventions focused on creative expression and the arts. Helping clients find social connection and emotional support by joining groups: rituals. Encouraging clients to take action. Practitioner’s inner work and education. Connecting clients with nature. |

| Clayton [41] | Conservation psychology | Fostering clients’ inner resilience: cognitive interventions. Helping clients find social connection and emotional support by joining groups. Encouraging clients to take action: collective action. |

| White [55] | Ecopsychology | Helping clients find social connection and emotional support by joining groups: joining established groups and organizations. Encouraging clients to take action. |

| Dockett [16] | Includes ecotherapy | Fostering clients’ inner resilience: cognitive interventions—shifting from catastrophizing towards a less black and white picture; emotion-focused interventions. Encouraging clients to take action: individual action and collective action. Practitioner’s inner work and education. Connecting clients with nature. |

| Hasbach [36] | Ecotherapy | Connecting clients with nature. |

| Koger [37] | Ecotherapy | Helping clients find social connection and emotional support by joining groups: joining established groups and organizations. Connecting clients with nature. |

| Kelsey [56] | Environmental education | Fostering clients’ inner resilience: cognitive interventions—shifting from catastrophizing towards a less black and white picture. |

| Bednarek [53] | Gestalt | Helping clients find social connection and emotional support by joining groups: rituals. Practitioner’s inner work and education. Connecting clients with nature. |

| Gillespie [54] * | Jungian depth psychology | Fostering clients’ inner resilience: interventions connecting clients with their lyrical self—interventions focused on dreams. Helping clients find social connection and emotional support by joining groups. |

| Kiehl [34] | Jungian depth psychology | Fostering clients’ inner resilience: meaning-focused/existential interventions. |

| Davenport [10] | Marriage and family therapy | Fostering clients’ inner resilience: meaning-focused/existential interventions. Helping clients find social connection and emotional support by joining groups. Practitioner’s inner work and education: grief awareness. |

| Baker [35] | Psychoanalysis | Fostering clients’ inner resilience: emotion-focused interventions. |

| Haseley [42] | Psychoanalysis | Fostering clients’ inner resilience: emotion-focused interventions—differentiating between distress related to the client’s history and distress due to eco-anxiety. Helping clients find social connection and emotional support by joining groups: joining established groups and organizations. |

| Lewis [39] | Psychoanalysis | Fostering clients’ inner resilience: meaning-focused/existential interventions—fostering optimism and hope; emotion-focused interventions. Helping clients find social connection and emotional support by joining groups. Encouraging clients to take action: collective action. |

| Lewis [44] | Psychoanalysis | Fostering clients’ inner resilience: meaning-focused/existential interventions—discussing and relativizing the social and systemic dimensions of climate change; emotion-focused interventions—differentiating between distress related to the client’s history and distress due to eco-anxiety. Encouraging clients to take action: collective action. Practitioner’s inner work and education. |

| Randall [30] | Psychoanalysis | Fostering clients’ inner resilience: meaning-focused/existential interventions—discussing and relativizing the social and systemic dimensions of climate change. Practitioner’s inner work and education. |

| Randall [32] | Psychoanalysis | Fostering clients’ inner resilience: emotion-focused interventions—grief. Helping clients find social connection and emotional support by joining groups: joining established groups and organizations. Practitioner’s inner work and education: grief awareness. |

| Randall [49] | Psychoanalysis | Fostering clients’ inner resilience: meaning-focused/existential interventions, emotion-focused interventions—grief. Encouraging clients to take action: individual and collective action. Practitioner’s inner work and education: grief awareness. |

| Australian Conservation Foundation [47] ** | Not identified | Fostering clients’ inner resilience: cognitive interventions; meaning-focused/existential interventions—fostering optimism and hope; emotion-focused interventions, self-care interventions. Helping clients find social connection and emotional support by joining groups. Encouraging the client to take action: individual action. Connecting clients with nature. |

| Büchs et al. [50] * | Not identified | Helping clients find social connection and emotional support by joining groups: joining established groups and organizations. |

| Burke [38] | Not identified | Fostering clients’ inner resilience: cognitive interventions—shifting from catastrophizing towards a less black and white picture; emotion-focused interventions. Encouraging clients to take action: individual action and collective action. |

| Clayton et al. [15] ** | Not identified | Fostering clients’ inner resilience: cognitive interventions; meaning focused/existential interventions. Helping clients find social connection and emotional support by joining groups. |

| Doherty and Clayton [33] | Not identified | Fostering clients’ inner resilience: emotion-focused interventions—grief. Encouraging clients to take action: individual and collective action. Practitioner’s inner work and education: grief awareness. |

| Good Grief Network [48] * | Not identified | Fostering clients’ inner resilience: cognitive interventions; meaning-focused/existential interventions; self-care interventions. Encouraging clients to take action. |

| Hayes [12] * | Not identified | Fostering clients’ inner resilience: cognitive interventions, interventions connecting clients with their lyrical self—interventions focused on creative expression and the arts. Helping clients find social connection and emotional support by joining groups. Connecting clients with nature. |

| Jaramillo [46] | Not identified | Fostering clients’ inner resilience: emotion-focused interventions—grief. |

| Kelly [51] * | Not identified | Fostering clients’ inner resilience: cognitive interventions; emotion-focused interventions; self-care interventions. Helping clients find social connection and emotional support by joining groups. Encouraging clients to take action. Connecting clients with nature. |

| Ojala [40] | Not identified | Fostering clients’ inner resilience: meaning-focused/existential interventions—fostering optimism and hope and discussing/relativizing the social and systemic dimensions of climate change. Encouraging clients to take action: collective action. |

| Pihkala [7] | Not identified | Fostering clients’ inner resilience: cognitive interventions— shifting from catastrophizing towards a less black and white picture; meaning-focused/existential interventions; interventions connecting clients with their lyrical self—interventions focused on creative expression and the arts. Helping clients find social connection and emotional support by joining groups: rituals. Practitioner’s inner work and education: grief awareness. |

| Pikhala [13] | Not identified | Fostering clients’ inner resilience: cognitive interventions; emotion-focused interventions—grief; self-care interventions; interventions connecting clients with their lyrical self—interventions focused on creative expression and the arts. Helping clients find social connection and emotional support by joining groups: joining established groups and organizations. Encouraging the client to take action-individual action. Practitioner’s inner work and education. |

| Sarchet [43] ** | Not identified | Fostering clients’ inner resilience: emotion-focused interventions. Helping clients find social connection and emotional support by joining groups. Encouraging clients to take action: individual action. Connecting clients with nature. |

| Seaman [26] * | Not identified | Fostering clients’ inner resilience: cognitive interventions; meaning-focused/existential interventions—discussing and relativizing the social and systemic dimensions of climate change, emotion-focused interventions—grief focused interventions. Helping clients find social connection and emotional support by joining groups—joining established groups and organizations. Practitioner’s inner work and education. |

| Shaffer [52] | Not identified | Fostering clients’ inner resilience: self-care interventions; interventions connecting clients with their lyrical self—interventions focused on creative expression and the arts. Helping clients find social connection and emotional support by joining groups. |

| Stokols et al. [31] | Not identified | Helping clients find social connection and emotional support by joining groups. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baudon, P.; Jachens, L. A Scoping Review of Interventions for the Treatment of Eco-Anxiety. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9636. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189636

Baudon P, Jachens L. A Scoping Review of Interventions for the Treatment of Eco-Anxiety. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(18):9636. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189636

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaudon, Pauline, and Liza Jachens. 2021. "A Scoping Review of Interventions for the Treatment of Eco-Anxiety" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 18: 9636. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189636

APA StyleBaudon, P., & Jachens, L. (2021). A Scoping Review of Interventions for the Treatment of Eco-Anxiety. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), 9636. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189636