Age and Emotional Distress during COVID-19: Findings from Two Waves of the Norwegian Citizen Panel

Abstract

:1. Introduction

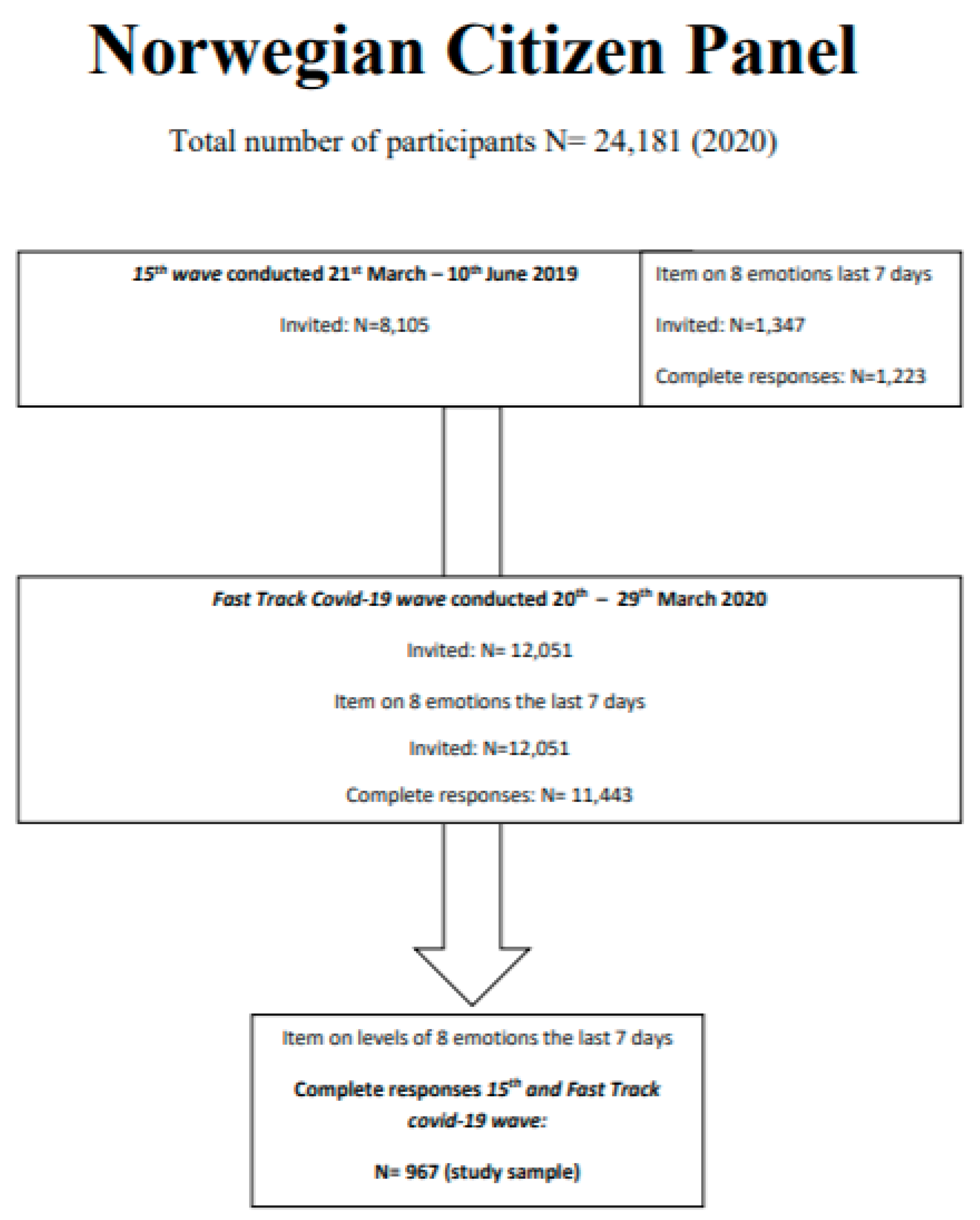

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

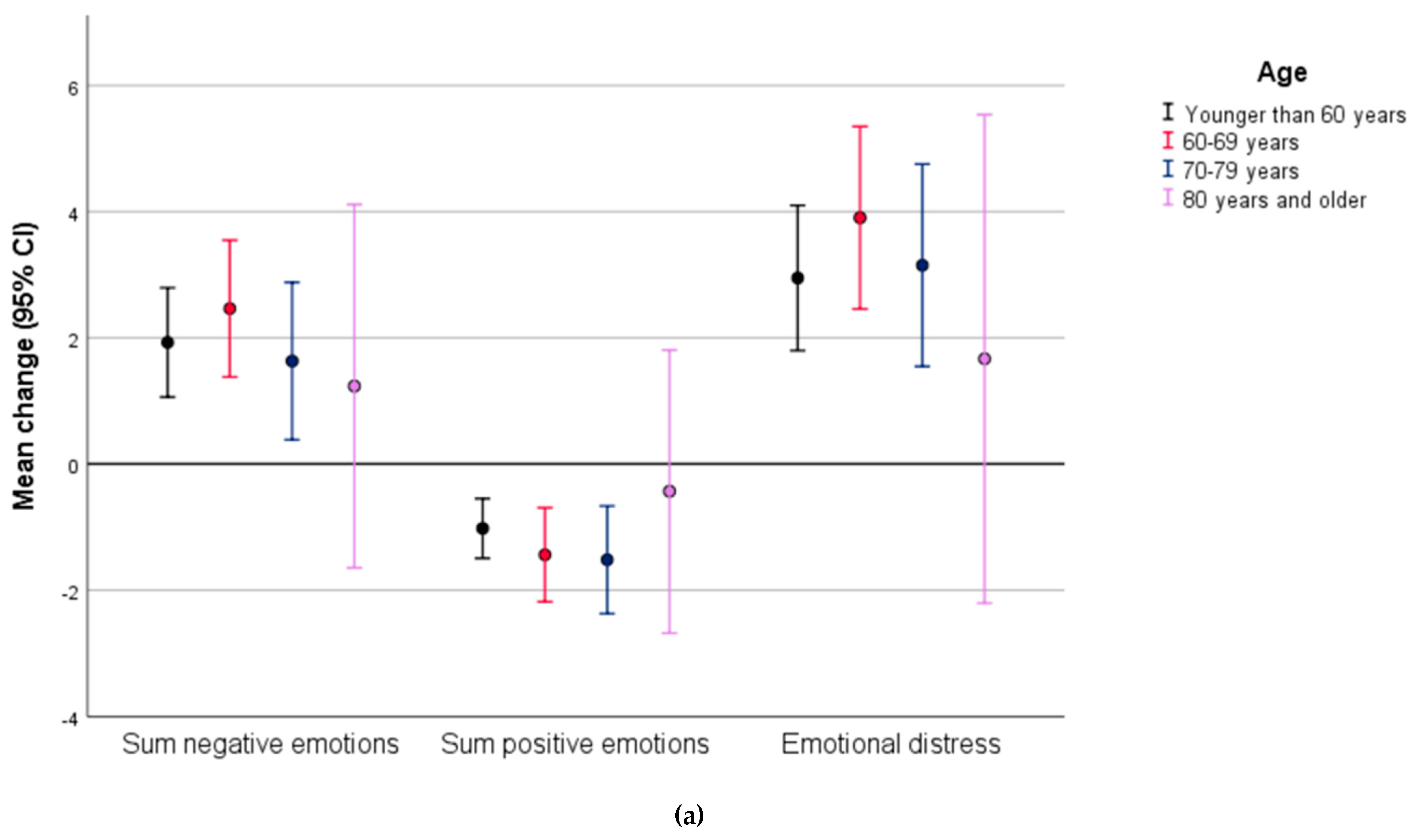

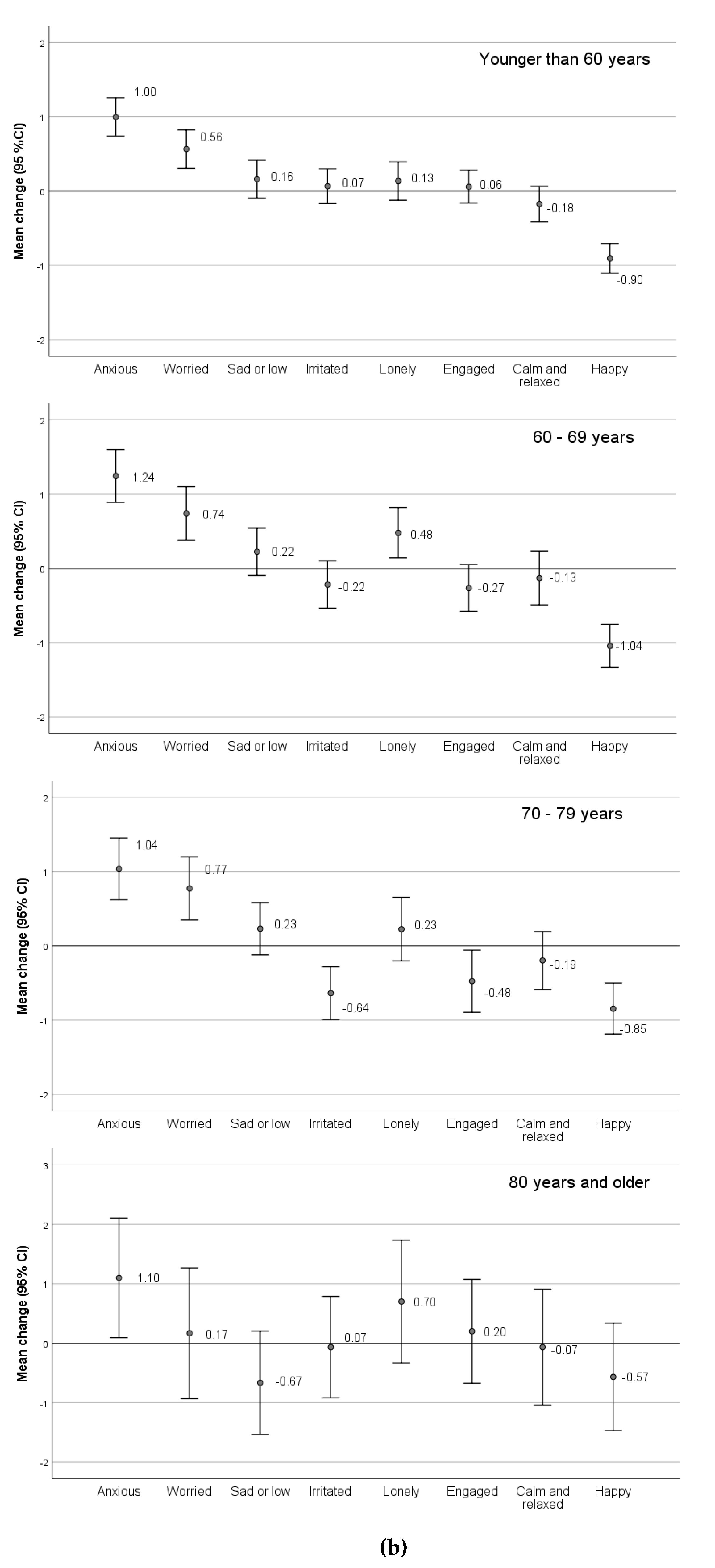

3.1. Change in Positive and Negative Emotions and Emotional Distress from Spring 2019 to COVID-19 Wave in March 2020

3.2. Relative Importance of Older Age Compared with Other Demographic-, Economic-, and Health-Related Factors on Level of Emotional Distress in the COVID-19 Wave in March 2020

3.3. Relative Importance of Older Age Compared with Gender and Education Predicting Change in Emotional Distress from Spring 2019 to COVID-19 Wave in March 2020

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| <60 Years N = 514 | 60–69 Years N = 255 | 70–79 Years N = 168 | ≥80 Years N = 30 | p # | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N(%)/Mean (st.dev) | N(%)/Mean (st.dev) | N(%)/Mean (st.dev) | N(%)/Mean (st.dev) | |||

| Gender (ref male) | ||||||

| female | 270 (52.5) | 130 (51.0) | 68 (40.5) | 14 (46.7) | 0.054 | |

| Level of education | 0.008 | |||||

| Primary school | 12 (2.3) | 16 (6.3) | 11 (6.5) | 2 (6.7) | ||

| High school | 132 (25.7) | 65 (25.5) | 35 (20.8) | 1 (3.3) | ||

| College/university | 283 (55.1) | 141 (55.3) | 96 (57.1) | 23 (76.7) | ||

| Missing | 87 (16.9) | 33 (12.9) | 26 (15.5) | 4 (13.3) | ||

| Expected household income in 2020 | <0.001 | |||||

| No change | ||||||

| 316 (61.4) | 207 (81.2) | 151 (90.0) | 30 (100) | |||

| Much lower | 46 (8.9) | 10 (3.9) | 3 (1.79) | 0 (0) | ||

| Lower | 125 (24.3) | 34 (13.7) | 12 (7.14) | 0 (0) | ||

| Higher | 25 (4.9) | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.60) | 0 (0) | ||

| Much higher | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Missing | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.60) | 0 (0) | ||

| Change in work situation | ||||||

| No | ||||||

| Yes | 346 (67.3) | 101 (39.6) | 17 10.1) | 2 (6.7) | <0.001 | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Importance of press conference from government * | 4.22 (0.96) | 4.39 (0.84) | 4.44 (0.77) | 4.33 (0.80) | 0.802 | |

| Missing | 9 (1.76) | 2 (0.78) | 5 (3.0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Uncertain whether infected by SARS-Cov2 | ||||||

| No | ||||||

| Yes | 194 (37.8) | 51 (20.0) | 17 (10.1) | 3 (10.0) | <0.001 | |

| Missing | 1 (0.02) | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Consider oneself vulnerable for infection with SARS-Cov2 ref no | ||||||

| Yes | 57 (11.1) | 82 (32.2) | 102 (60.7) | 23 (76.7) | <0.001 | |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Consider cohabitant vulnerable for infection with SARS-Cov2 | ||||||

| No | ||||||

| Yes | 417 (81.7) | 174 (68.5) | 93 (55.7) | 21 (72.4) | <0.001 | |

| Missing | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Self-rated health * | 2.17 (0.90) | 2.48 (0.92) | 2.67 (0.88) | 2.73 (0.78) | <0.001 | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Self-rated risk of infection with SARS-Cov2 * | 3.22 (1.1) | 2.69 (0.92) | 2.41 (0.88) | 2.40 (0.93) | <0.001 | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Content with life * | 3.97 (0.77) | 4.08 (0.66) | 4.13 (0.74) | 4.1 (0.66) | 0.057 | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Confidence in others ** | 6.62 (2.24) | 6.96 (2.25) | 7.02 (2.43) | 7.60 (2.81) | 0.023 | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Emotional distress @ | −0.92 (13.1) | −5.23 (12.3) | −6.28 (11.9) | −7.6 (13.1) | <0.001 | |

References

- Czeisler, M.; Lane, R.I.; Wiley, J.F.; Czeisler, C.A.; Howard, M.E.; Rajaratnam, S.M.W. Follow-Up Survey of US Adult Reports of Mental Health, Substance Use, and Suicidal Ideation During the COVID-19 Pandemic, September 2020. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2037665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorillo, A.; Gorwood, P. The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and implications for clinical practice. Eur. Psychiatry 2020, 63, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Unutzer, J.; Kimmel, R.J.; Snowden, M. Psychiatry in the age of COVID-19. World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 130–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marazziti, D.; Stahl, S.M. The relevance of COVID-19 pandemic to psychiatry. World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghebreyesus, T.A. Addressing mental health needs: An integral part of COVID-19 response. World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 129–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, E.A.; O’Connor, R.C.; Perry, V.H.; Tracey, I.; Wessely, S.; Arseneault, L.; Ballard, C.; Christensen, H.; Silver, R.C.; Everall, I.; et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, D. The impact of Covid-19 pandemic on elderly mental health. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 35, 1466–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pubmed. Emotional Distress Definition 2020. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/?term=%22psychological%20distress%22%5BMeSH%20Terms%5D%20OR%20emotional%20distress%5BText%20Word%5D&cmd=DetailsSearch (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- Kang, S.-J.; Jung, S.I. Age-Related Morbidity and Mortality among Patients with COVID-19. Infect. Chemother. 2020, 52, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedde, M.H.; Husebo, B.S.; Erdal, A.; Puaschitz, N.G.; Vislapuu, M.; Angeles, R.C.; Berge, L.I. Access to and interest in assistive technology for home-dwelling people with dementia during the COVID-19 pandemic (PAN.DEM). Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2021, 32, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, J.; Jain, R.; Golamari, R.; Vunnam, R.; Sahu, N. COVID-19 in the geriatric population. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 35, 1437–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, Z.I.; Jose, P.E.; Cornwell, E.Y.; Koyanagi, A.; Nielsen, L.; Hinrichsen, C.; Meilstrup, C.; Madsen, K.R.; Koushede, V. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and symptoms of depression and anxiety among older Americans (NSHAP): A longitudinal mediation analysis. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e62–e70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chan, S.M.S.; Chiu, F.K.H.; Lam, C.W.L.; Leung, P.Y.V.; Conwell, Y. Elderly suicide and the 2003 SARS epidemic in Hong Kong. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2006, 21, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yip, P.S.; Cheung, Y.T.D.; Chau, P.H.; Law, Y. The Impact of Epidemic Outbreak: The case of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and suicide among older adults in Hong Kong. Crisis 2010, 31, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, A.; Blakemore, T.; Bevis, M. Older people as assets in disaster preparedness, response and recovery: Lessons from regional Australia. Ageing Soc. 2015, 37, 517–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweizer, S.; Stretton, J.; Van Belle, J.; Price, D.; Calder, A.J.; Can, C.; Dalgleish, T. Age-Related decline in positive emotional reactivity and emotion regulation in a population-derived cohort. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2019, 14, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahia, I.V.; Jeste, D.V.; Reynolds, C.F. Older Adults and the Mental Health Effects of COVID-19. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 324, 2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Bergen. The Norwegian Citizen Panel. Available online: https://www.uib.no/en/citizen (accessed on 4 September 2021).

- Statistics Norway. Key Figures for the Population 2020. Available online: https://www.ssb.no/en/befolkning/nokkeltall/population (accessed on 4 September 2021).

- University of Bergen. DIGSSCORE Status Report. 2019. Available online: https://www.uib.no/sites/w3.uib.no/files/attachments/digsscore_status_report.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2021).

- Ideas2evidence. Available online: https://www.ideas2evidence.com/en/home (accessed on 4 September 2021).

- The National Population Registry. Available online: https://www.skatteetaten.no/en/person/national-registry/about/this-is-the-national-registry/ (accessed on 4 September 2021).

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software; Release 13; College Station TSL: College Station, TX, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. Released 2017; IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows VA, NY; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Viertiö, S.; Kiviruusu, O.; Piirtola, M.; Kaprio, J.; Korhonen, T.; Marttunen, M.; Suvisaari, J. Factors contributing to psychological distress in the working population, with a special reference to gender difference. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persson, L.; Larsson, B.; Nived, K.; Eberhardt, K. The development of emotional distress in 158 patients with recently diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis: A prospective 5-year follow-up study. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2005, 34, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Løvstad, M.; Manum, G.; Wisløff-Aase, K.; Hafstad, G.S.; Ræder, J.; Larsen, I.; Stanghelle, J.K.; Schanke, A.-K. Persons injured in the 2011 terror attacks in Norway—Relationship between post-traumatic stress symptoms, emotional distress, fatigue, sleep, and pain outcomes, and medical and psychosocial factors. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 42, 3126–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.; Lodge, C.; Vollans, S.; Harwood, P.J. Predictors of psychological distress following major trauma. Injury 2019, 50, 1577–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvarani, V.; Ardenghi, S.; Rampoldi, G.; Bani, M.; Cannata, P.; Ausili, D.; Di Mauro, S.; Strepparava, M.G. Predictors of psychological distress amongst nursing students: A multicenter cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ. Pr. 2020, 44, 102758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabasawa, K.; Tanaka, J.; Komata, T.; Matsui, K.; Nakamura, K.; Ito, Y.; Inoue, S. Determination of specific life changes on psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achdut, N.; Refaeli, T. Unemployment and Psychological Distress among Young People during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Psychological Resources and Risk Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.; Lipsitz, O.; Nasri, F.; Lui, L.M.; Gill, H.; Phan, L.; Chen-Li, D.; Iacobucci, M.; Ho, R.; Majeed, A.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, S.A.; Salmon, P.; Hayes, G.; Byrne, A.; Fisher, P. Predictors of emotional distress a year or more after diagnosis of cancer: A systematic review of the literature. Psycho Oncol. 2018, 27, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, P.L.; Salmon, P.; Heffer-Rahn, P.; Huntley, C.; Reilly, J.; Cherry, M.G. Predictors of emotional distress in people with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review of prospective studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 276, 752–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrer, P. COVID-19 health anxiety. World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 307–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christiansen, D.M. Examining Sex and Gender Differences in Anxiety Disorders. A Fresh Look Anxiety Disord. 2015, 17–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ding, Y.; Yang, J.; Ji, T.; Guo, Y. Women Suffered More Emotional and Life Distress than Men during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Pathogen Disgust Sensitivity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogos, A.; Ney, L.J.; Seymour, N.; Van Rheenen, T.E.; Felmingham, K.L. Sex differences in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder: Are gonadal hormones the link? Br. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 176, 4119–4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, K.-Y.; Kok, A.A.L.; Eikelenboom, M.; Horsfall, M.; Jörg, F.; Luteijn, R.A.; Rhebergen, D.; van Oppen, P.; Giltay, E.J.; Penninx, B.W.J.H. The mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with and without depressive, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive disorders: A longitudinal study of three Dutch case-control cohorts. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 8, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fancourt, D.; Steptoe, A.; Bu, F. Trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms during enforced isolation due to COVID-19 in England: A longitudinal observational study. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 8, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salameh, P.; Hajj, A.; Badro, D.A.; Selwan, C.A.; Aoun, R.; Sacre, H. Mental Health Outcomes of the COVID-19 Pandemic and a Collapsing Economy: Perspectives from a Developing Country. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 294, 113520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godinić, D.; Obrenovic, B.; Khudaykulov, A. Effects of Economic Uncertainty on Mental Health in the COVID-19 Pandemic Context: Social Identity Disturbance, Job Uncertainty and Psychological Well-Being Model. Int. J. Innov. Econ. Dev. 2020, 6, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrman, H.; Stewart, D.E.; Diaz-Granados, N.; Berger, E.L.; Jackson, B.; Yuen, T. What is Resilience? Can. J. Psychiatry 2011, 56, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sams, N.; Fisher, D.M.; Mata-Greve, F.; Johnson, M.; Pullmann, M.D.; Raue, P.J.; Renn, B.N.; Duffy, J.; Darnell, D.; Fillipo, I.G.; et al. Understanding Psychological Distress and Protective Factors Amongst Older Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaiber, P.; Wen, J.H.; DeLongis, A.; Sin, N.L. The Ups and Downs of Daily Life During COVID-19: Age Differences in Affect, Stress, and Positive Events. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2020, 76, e30–e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, F.; Steptoe, A.; Fancourt, D. Loneliness during a strict lockdown: Trajectories and predictors during the COVID-19 pandemic in 38,217 United Kingdom adults. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 265, 113521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaid, D. Viewpoint: Investing in strategies to support mental health recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. Psychiatry 2021, 64, e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzman, M.R.; Curkovic, M.; Wasserman, D. Principles of mental health care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. Psychiatry 2020, 63, e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, D.E.; Appelbaum, P.S. COVID-19 and psychiatrists’ responsibilities: A WPA position paper. World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 406–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Last Seven Days, to Which Extent Did You Feel | <60 Years N = 514 % (Ref) | 60–69 Years N = 255 %/OR/p * | 70–79 Years N = 168 %/OR/p * | ≥80 Years N = 30 %/OR/p * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative emotions: | ||||

| Anxious | 56.4 | 56.1/0.99/0.928 | 52.4/0.85/0.361 | 43.3/0.59/0.165 |

| Worried | 50.3 | 46.3/0.85/0.283 | 48.2/0.92/0.625 | 46.7/0.86/0.692 |

| Sad or low | 43.3 | 40.0/0.86/0.344 | 35.1/0.70/0.054 | 23.3/0.39/0.035 |

| Irritated | 42.6 | 32.9/0.66/0.010 | 25.0/0.45/<0.001 | 36.7/0.78/0.523 |

| Lonely | 34.4 | 35.3/1.04/0.814 | 32.7/0.93/0.687 | 36.7/1.10/0.803 |

| Positive emotions: | ||||

| Engaged | 40.5 | 44.6/1.05/0.770 | 47.6/1.34/0.104 | 50.0/1.47/0.305 |

| Calm and relaxed | 41.1 | 39.6/0.94/0.701 | 39.3/0.93/0.686 | 40.0/0.96/0.909 |

| Happy | 55.5 | 53.7/0.93/0.651 | 51.2/0.84/0.336 | 43.3/0.61/0.199 |

| Sum scores | ||||

| Sum of five negative emotions | 56.8 | 53.7/0.88/0.418 | 53.0/0.86/0.385 | 53.3/0.87/0.709 |

| Sum of three positive emotions | 55.3 | 53.7/0.94/0.689 | 60.7/1.25/0.215 | 53.3/0.93/0.837 |

| Emotional distress @ | 58.2 | 60.4/1.10/0.556 | 61.9/1.16/0.393 | 53.3/0.82/0.602 |

| Fixed Effects | Beta (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Age groups (ref born 1960 and later) | ||

| 1950–1959 | −1.87 (−3.71, −0.04) | 0.046 |

| 1940–1949 | −2.34 (−4.82, 0.14) | 0.064 |

| 1939 and earlier | −4.19 (−8.66, 0.27) | 0.066 |

| Gender (ref male) | ||

| female | 2.81 (1.34, 4.28) | <0.001 |

| Level of education (ref primary school) | ||

| High school | 2.40 (−1.02, 5.82) | 0.168 |

| College/university | 3.04 (−0.30, 6.38) | 0.074 |

| Expected household income in 2020 (ref no change) | ||

| Much lower | 5.09 (2.00, 8.17) | 0.001 |

| Lower | 1.16 (−0.77, 3.09) | 0.239 |

| Higher | −1.23 (−5.34, 2.87) | 0.556 |

| Much higher | −7.60 (−21.69, 6.47) | 0.290 |

| Change in work situation (ref no) | ||

| Yes | −0.18 (−1.90, 1.53) | 0.834 |

| Importance of press conference from government * | 0.10 (−0.71, 0.92) | 0.803 |

| Uncertain whether infected by SARS-Cov2 (ref no) | ||

| Yes | 2.92 (1.21, 4.63) | 0.001 |

| Consider oneself vulnerable for infection with SARS-Cov2 (ref no) | ||

| Yes | −1.31 (−3.32, 0.69) | 0.199 |

| Consider cohabitant vulnerable for infection with SARS-Cov2 (ref no) | ||

| Yes | −1.64 (−3.37, 0.08) | 0.062 |

| Self-rated health * | 1.32 (0.40, 2.34) | 0.005 |

| Self-rated risk of infection with SARS-Cov2 * | 1.77 (1.01, 2.53) | <0.001 |

| Content with life * | −7.72 (−8.78, −6.66) | <0.001 |

| Confidence in others ** | −0.31 (−0.65, 0.02) | 0.066 |

| Random effect | Var_cons | |

| County | 1.72 (0.34, 8.69) |

| Author/Journal/Year | Design | Population (n) | Age | Outcome | Predictors | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viertio/BMC Public Health/2021/([25]) | Cross-sectional | Finnish Regional Health and Well-being Study (n = 34,468) | 20–65 years | Mental Health Inventory-5 (MHI-5) | Female gender, loneliness, job dissatisfaction, and family–work conflict | Protective factors: able to balance work and family life |

| Persson/Scan J Rheumatol 2005 [26] | Prospective | Early rheumatoid patients in Sweden (n = 158) | ≥18 years | Symptom Checklist Scale (SCL-90) | Level of distress at baseline, female gender, young age, cohabiting, less social support | Disease activity weakly associated with distress |

| Løvstad/Disabil Rehabil 2020 [27] | Prospective | Survivors of terror attacks in Norway (n = 30) | 19–71 years | Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (HSCL-8) | Neuroticism | Protective factors: resilience, optimism, social support. Injury severity not associated with emotional distress |

| Johnson/Injury/2019 [28] | Prospective | Patient admitted to a major trauma centre in the UK (n = 114) | All ages | CORE-10 | High score on posttraumatic adjustment screen (PAS) at baseline, living outside hospital area. | No association between risk of distress development and sociodemographic factors and overall injury severity |

| Salvarani/Nursing Education Practice/2020 [29] | Cross-sectional | Nursing students affiliated with teaching hospitals in Italy (n = 622) | Young adults | GHQ-12, Italian version | Emotional regulation difficulties and empathic personal distress | No gender differences, senor students and students with high mindfulness score had lower distress. |

| Kabasawa/Plos One 2021 [30] | Cross-sectional COVID-19 sample | Workers in Japan (n = 609) | Adults | Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6) | Female gender, younger age, increased workload. | ‘Staying at home’ regarded biggest life change. |

| Achdut/Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020 [31] | Cross-sectional COVID-19 sample | Young Israeli people (n = 389) | 20–35 | Modified items from the Israeli Social Survey (ISS) | Unemployment, financial strain, loneliness. | Protective factors were trust, optimism, and sense of mastery. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Berge, L.I.; Gedde, M.H.; Husebo, B.S.; Erdal, A.; Kjellstadli, C.; Vahia, I.V. Age and Emotional Distress during COVID-19: Findings from Two Waves of the Norwegian Citizen Panel. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9568. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189568

Berge LI, Gedde MH, Husebo BS, Erdal A, Kjellstadli C, Vahia IV. Age and Emotional Distress during COVID-19: Findings from Two Waves of the Norwegian Citizen Panel. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(18):9568. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189568

Chicago/Turabian StyleBerge, Line I., Marie H. Gedde, Bettina S. Husebo, Ane Erdal, Camilla Kjellstadli, and Ipsit V. Vahia. 2021. "Age and Emotional Distress during COVID-19: Findings from Two Waves of the Norwegian Citizen Panel" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 18: 9568. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189568

APA StyleBerge, L. I., Gedde, M. H., Husebo, B. S., Erdal, A., Kjellstadli, C., & Vahia, I. V. (2021). Age and Emotional Distress during COVID-19: Findings from Two Waves of the Norwegian Citizen Panel. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), 9568. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189568