Evaluation of an Online Gottman’s Psychoeducational Intervention to Improve Marital Communication among Iranian Couples

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Study Background

1.2. Problem Statement

1.3. Summary of the Theories and Literature

1.3.1. Family Communication Theory

- More negativity than positivity;

- Escalation of negative effect;

- Emotional disengagement and withdrawal;

- The failure of repair attempts;

- Negative sentiment override (NSO);

- Maintaining vigilance and physiological arousal;

- Solvable problems and perpetual issues.

1.3.2. Gottman Couple Theory

1.3.3. Reasoning for Selection of Communication Theory and Gottman’s Theory, the Alignment of Theories

2. Method

2.1. Screening and Selection Procedure

2.2. Data Collection Tools

2.3. Description of the O-GPI Protocol

- Build love maps;

- Share fondness and admiration;

- Turn toward each other;

- Positive perspective;

- Manage conflict;

- Make life dreams come true;

- Create shared meaning.

2.4. Statistical Data Analysis

3. Result

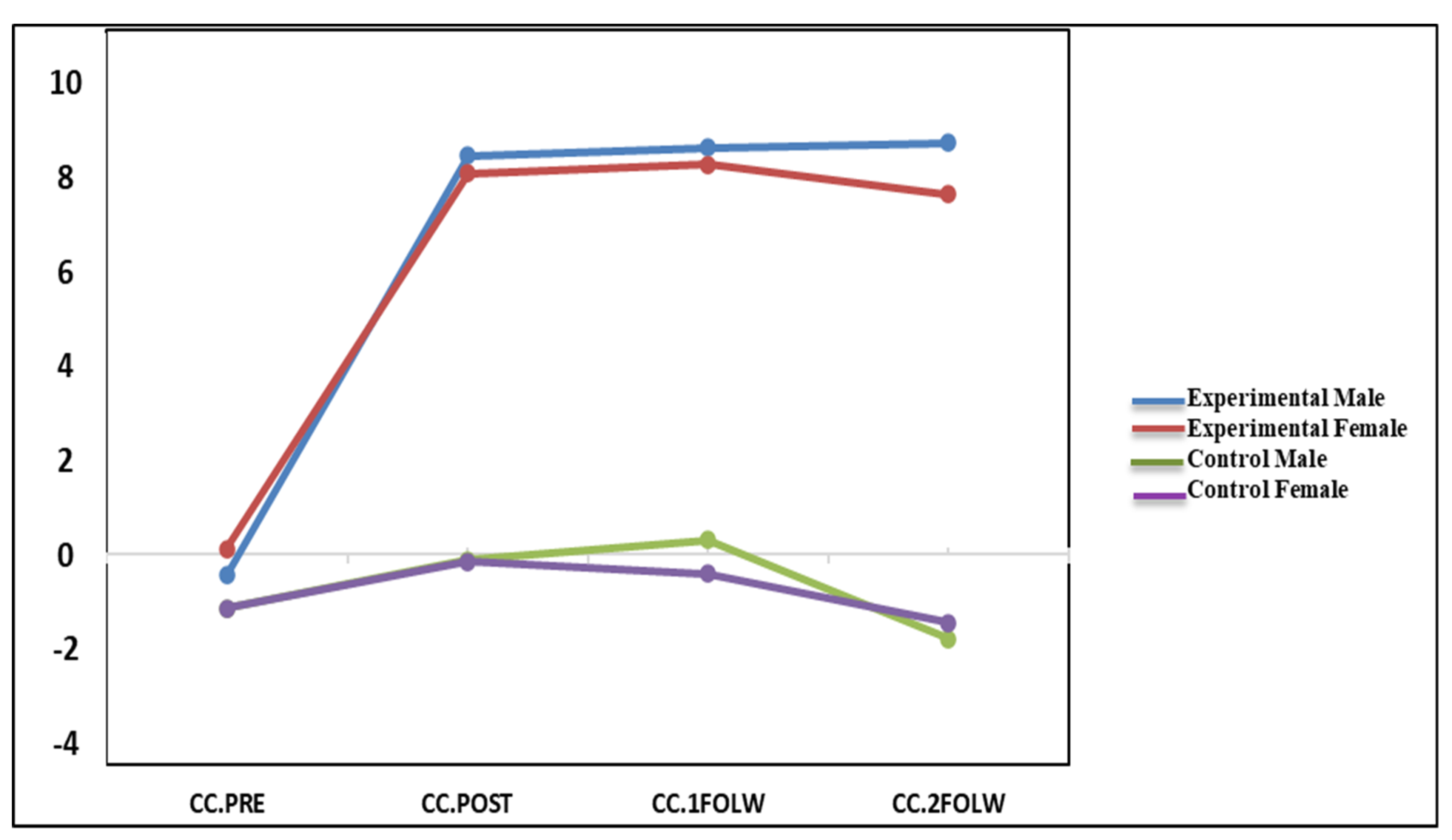

3.1. Constructive Communication

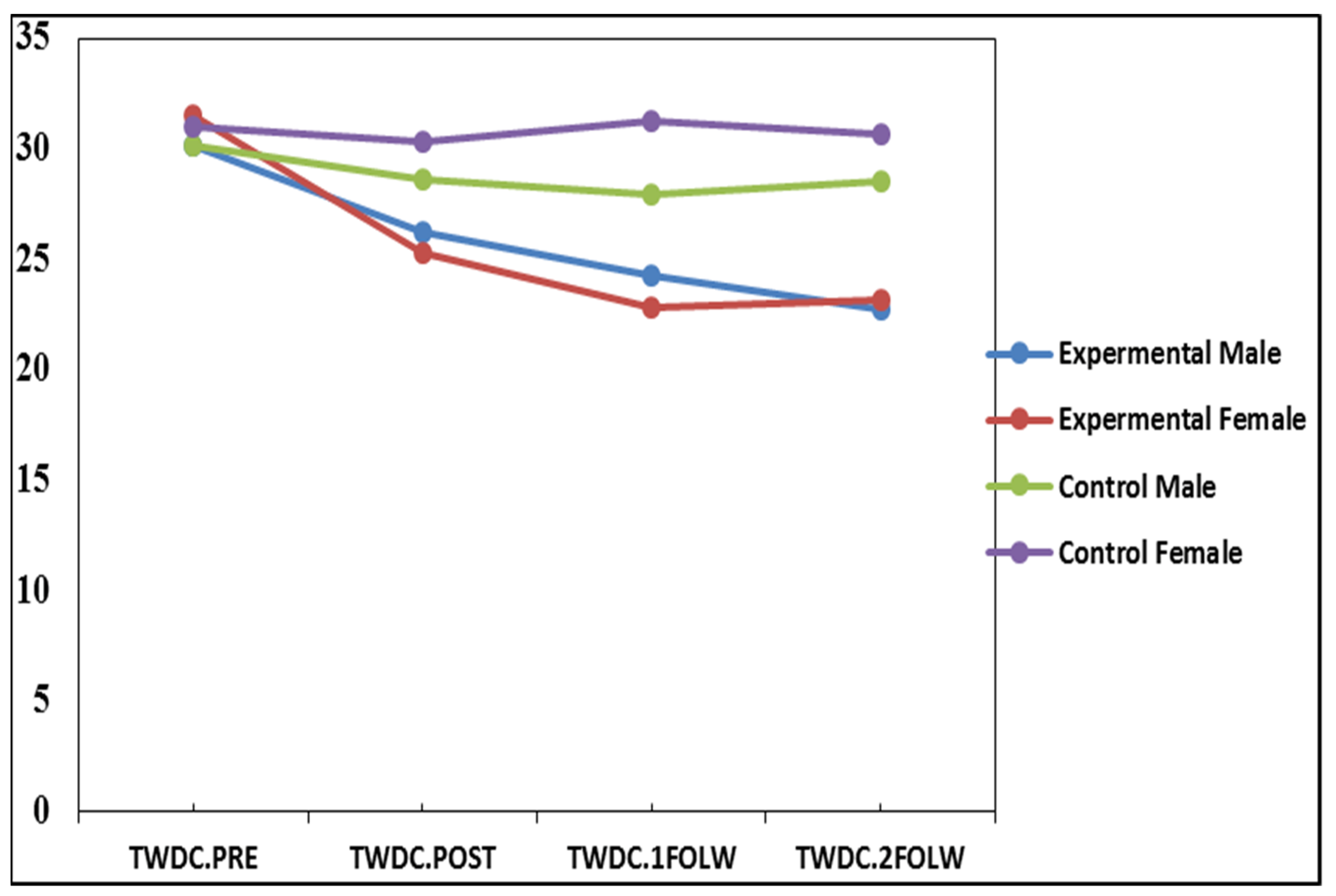

3.2. Demand–Withdraw Communication

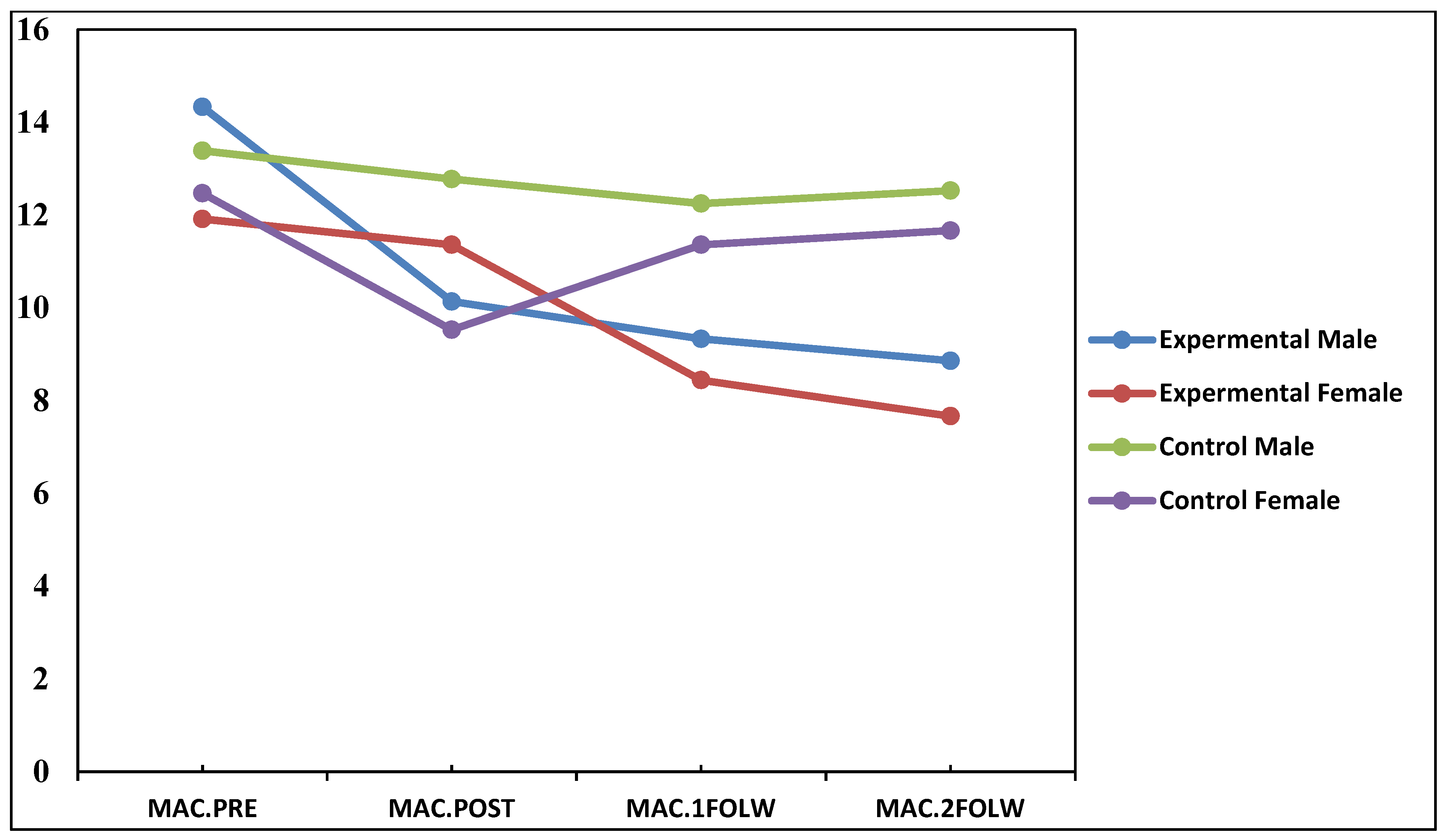

3.3. Mutual Avoidance Communication

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications of Results

4.2. Limitations

- Sample characteristics. The generalizability of this study is limited only to Iranian heterosexual couples residing in Shiraz.

- Methodology. The experimental design, randomization and minimization of individual differences were conducted; however, it was impossible to rule out all confounding variables, such as their motivation and cooperation rates, particularly in online sessions. Additionally, it is highly likely that participants had other information sources, such as friends, the Internet, TV and books, which could be used to improve their marital quality. This is not something that the researcher could control.

- Measurement tools. Though participants were reassured that their responses would be protected and anonymized by the researcher, it is probable that some participants answered questionnaires with low confidence or for achieving more social acceptance. It is also possible that the accurate meaning of the questions was misunderstood and some couples avoided seeking clarification for each question.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kansky, J. What’s love got to do with it? Romantic relationships and well-being. In Handbook of Well-Being; DEF Publishers: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman, J.; Silver, N. What Makes Love Last?: How to Build Trust and Avoid Betrayal; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Walen, H.R.; Lachman, M.E. Social support and strain from partner, family, and friends: Costs and benefits for men and women in adulthood. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2000, 17, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, D.; Springer, K.W. Advances in families and health research in the 21st century. J. Marriage Fam. 2010, 72, 743–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottman, J.; Gottman, J. In bridging the couple chasm, Gottman Couple’s Therapy: A new research-based approach. In A Workshop for Clinicians; The Gottman Institute: Seattle, WA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman, J.; Gottman, J. The natural principles of love. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2017, 9, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, A.; Eldridge, K.; Catta-Preta, A.B.; Lim, V.R.; Santagata, R. Cross-cultural consistency of the demand/withdraw interaction pattern in couples. J. Marriage Fam. 2006, 68, 1029–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldridge, K.A.; Christensen, A. Demand-withdraw communication during couple conflict: A review and analysis. In Understanding Marriage: Developments in the Study of Couple Interaction; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002; pp. 289–322. [Google Scholar]

- Moradi, M. The investigation of the marriage and divorce status in tabriz. J. Hist. Cult. Art Res. 2017, 6, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percheski, C.; Meyer, J.M. Health and union dissolution among parenting couples: Differences by gender and marital status. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2018, 59, 569–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavner, J.A.; Bradbury, T.N. Trajectories and maintenance in marriage and long-term committed relationships. In New Directions in the Psychology of Close Relationships; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 28–44. [Google Scholar]

- Trost, J. 25. The family life cycle. A problematic concept. In The Family Life Cycle in European Societies; De Gruyter Mouton: Berlin, Germany, 2019; pp. 467–482. [Google Scholar]

- Overall, N.C.; Chang, V.T.; Pietromonaco, P.R.; Low, R.S.; Henderson, A.M. Partners’ Attachment Insecurity and Stress Predict Poorer Relationship Functioning during COVID-19 Quarantines. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietromonaco, P.R.; Overall, N.C. Applying relationship science to evaluate how the COVID-19 pandemic may impact couples’ relationships. Am. Psychol. 2020, 76, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divorce Rate by Country 2021. Review, W.P. Retrieved from Moscow Population 2020. Available online: https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/divorce-rates-by-countryhttps://worldpopulationreview.com/worldcities/moscow-population.2020 (accessed on 27 July 2021).

- Olson, D.; DeFrain, J.; Skogrand, L. Marriages and Families: Intimacy, Diversity, and Strengths; McGraw-Hill: Nova Iorque, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Askari, M. Effects of Communication and Conflict Resolution Skills Training on Marital Satisfaction and Mental Health among Iranian Couples; Universiti Putra Malaysia: Serdang, Malaysia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Farnam, F.; Pakgohar, M.; Mir-mohammadali, M. Effect of pre-marriage counseling on marital satisfaction of Iranian newlywed couples: A randomized controlled trial. Sex. Cult. 2011, 15, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iran Data Portal. Available online: http://irandataportal.syr.edu/ministry-of-interior2015 (accessed on 27 July 2021).

- Amanat, M. Nationalism and social change in contemporary Iran. In Irangeles; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2020; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Babaee, S.N.; Ghahari, S. Effectiveness of communication skills training on intimacy and marital adjustment among married women. Int. J. Med. Res. Health Sci. 2016, 5, 375–380. [Google Scholar]

- Haris, F.; Kumar, A. Marital satisfaction and communication skills among married couples. Indian J. Soc. Res. 2018, 59, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Tavakolizadeh, J.; Nejatian, M.; Soori, A. The Effectiveness of communication skills training on marital conflicts and its different aspects in women. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 171, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Deylami, N. Marriage counseling with iranian couples. In Intercultural Perspectives on Family Counseling; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sillars, A.; Canary, D.J.; Vangelisti, A. Conflict and relational quality in families. In The Routledge Handbook of Family Communication; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 338–357. [Google Scholar]

- Caughlin, J.P.; Sharabi, L.L. A communicative interdependence perspective of close relationships: The connections between mediated and unmediated interactions matter. J. Commun. 2013, 63, 873–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, H.C.; Altman, N.; Hsueh, J.; Bradbury, T.N. Effects of relationship education on couple communication and satisfaction: A randomized controlled trial with low-income couples. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 84, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.F.; Johnson, L.N. Couples’ depression and relationship satisfaction: Examining the moderating effects of demand/withdraw communication patterns. J. Fam. Ther. 2018, 40, S63–S85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manalel, J.A.; Birditt, K.S.; Orbuch, T.L.; Antonucci, T.C. Beyond destructive conflict: Implications of marital tension for marital well-being. J. Fam. Psychol. 2019, 33, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshtaghi, S. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of life skills training on marital satisfaction of couples. J. Psychol. Achiev. 2018, 25, 111–128. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein, J. The Good Marriage: How and Why Love Lasts; Plunkett Lake Press: Lexington, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Deylami, N.; Hassan, S.A.; Baba, M.B.; Kadir, R.A. Effectiveness of Gottman’s psycho educational intervention on constructive communication among married women. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2015, 5, 97. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman, J.M.; Driver, J.L. Dysfunctional marital conflict and everyday marital interaction. J. Divorce Remarriage 2005, 43, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, H.S.; Jaremka, L.M.; Guichard, A.C.; Ford, M.B.; Collins, N.L.; Feeney, B.C. Feeling supported and feeling satisfied: How one partner’s attachment style predicts the other partner’s relationship experiences. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2007, 24, 535–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karney, B.R.; Bradbury, T.N. The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, methods, and research. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 118, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madahi, M.E.; Samadzadeh, M.; Javidi, N. The communication patterns & satisfaction in married students. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 84, 1190–1193. [Google Scholar]

- Markman, H.J.; Rhoades, G.K.; Stanley, S.M.; Peterson, K.M. A randomized clinical trial of the effectiveness of premarital intervention: Moderators of divorce outcomes. J. Fam. Psychol. 2013, 27, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, R. Why marriages last. Aust. Inst. Fam. Stud. 2002, 26, 2–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazi-Moghadam, S. A Qualitative Study of the Perceived Attitudes toward Counseling and Effective Counseling Practices in Working with Clients of Iranian Origin; Minnesota University: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gharagozloo, N.; Moradhaseli, M.; Atadokht, A. Comparing the Effectiveness of Face-to-Face and Virtual Cognitive-Behavioral Couples Therapy on the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Extra-Marital Relations; University of Mohaghegh Ardabili: Ardabil, Iran, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rolnick, A. Theory and Practice of Online Therapy: Internet-Delivered Interventions for Individuals, Groups, Families, and Organizations; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ajeli Lahiji, L.; Behzadi Pour, S.; Besharat, M.A. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Training Based on Gottman’s Theory on Marital Conflicts and Marital Instability. Health Educ. Health Promot. 2016, 4, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Brand, C.E. Initial Qualitative Exploration of Gottman’s Couples Research: A Workshop from the Participants’ Perspective; Florida State University: Tallahassee, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Deylami, N. Dyadic Effect of Gottman’s Psycho-Educational Intervention and Mediated Effect of Adult Attachment Style on Marital Communication among Iranian Couples in Shiraz; Universiti Putra Malaysia: Serdang, Malaysia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi, M.; Zahrakar, K.; Jahangiri, J.; Davarniya, R.; Shakarami, M.; Morshedi, M. Assessing the efficiency of educational intervention based on Gottman’s model on marital intimacy of women. J. Health 2017, 8, 74–84. [Google Scholar]

- Rajaei, A.; Daneshpour, M.; Robertson, J. The effectiveness of couples therapy based on the Gottman method among Iranian couples with conflicts: A quasi-experimental study. J. Couple Relatsh. Ther. 2019, 18, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, S.; Zahrakar, K. Effectiveness of Educating Marital Skills Based on Gottman’s Approach on of Woman’s communication patterns. Couns. Cult. Psycotherapy 2020, 11, 253–278. [Google Scholar]

- Ostenson, J.A. The Neglect of Divorce in Marital Research: An Ontological Analysis of The Work of John Gottman; Brigham Young University: Provo, UT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Aghakhani, N.; Eftekhari, A.; Zare Kheirabad, A.; Mousavi, E. Study of the effect of various domestic violence against women and related factors in women who referred to the forensic medical center in Urmia city-Iran 2012–2013. Sci. J. Forensic Med. 2012, 18, 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- AhmadiGatab, T.; Khamen, A.B.Z. Relation between communication skills and marital-adaptability among university students. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 30, 1959–1963. [Google Scholar]

- Bidokhti, N.M.; Pourshanbaz, A. The relationship between attachment styles, marital satisfaction and sex guilt with sexual desire in Iranian women. Iran. J. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 1, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahimi, E.; Ali Kimiaei, S. The study of the relationship among marital satisfaction, attachment styles, and communication patterns in divorcing couples. J. Divorce Remarriage 2014, 55, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isanezhad, O. Effectiveness of relationship enhancement on marital quality of couples. Int. J. Behav. Sci. 2010, 4, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Isanezhad, O.; Ahmadi, S.-A.; Bahrami, F.; Baghban-Cichani, I.; Farajzadegan, Z.; Etemadi, O. Factor structure and reliability of the Revised Dyadic Adjustment Scale (RDAS) in Iranian population. Iran. J. Psychiatry Behav. Sci. 2012, 6, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Moafi, F.; Dolatian, M.; Sajjadi, H.; Alimoradi, Z.; Mirabzadeh, A.; Mahmoodi, Z. Domestic violence and its associated factors in Iran: According to World Health Organization model. Pajoohandeh J. 2014, 19, 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, J.W.; Bradford, K.; Higginbotham, B.J.; Skogrand, L. Relationship help-seeking: A review of the efficacy and reach. Marriage Fam. Rev. 2016, 52, 781–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, M.A. Family communication patterns theory: Observations on its development and application. J. Fam. Commun. 2004, 4, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangelisti, A.L. The Routledge Handbook of Family Communication; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Barth, J.A. Case study evaluation of a theory and implications for a beginning therapist: Gottmans’ Sound Marital House. In The Chicago School of Professional Psychology; The Chicago School of Professional Psychology at Los Angeles: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zainudin, Z.N.; Hassan, S.A.; Ahmad, N.A.; Yusop, Y.M.; Othman, W.N.W.; Alias, B.S. A comparison of a client’s satisfaction between online and face-to-face counselling in a school setting. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2021, 29, 135–153. [Google Scholar]

- Zainudin, Z.N.; Yusop, Y.M.; Hassan, S.A.; Alias, B.S. The effectiveness of cybertherapy for the introvert and extrovert personality traits. Malays. J. Med. Health Sci. 2019, 15, 105–109. [Google Scholar]

- Alareqe, N.A.; Roslan, S.; Taresh, S.M.; Nordin, M.S. Universality and Normativity of the Attachment Theory in Non-Western Psychiatric and Non-Psychiatric Samples: Multiple Group Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opel, K.C. Attachment and Demand/Withdraw Behavior in Couple Interactions: The Moderating Role of Conflict Level; University of Maryland: College Park, MD, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, A.F.; Gottman, J.M. The specific affect coding system. In Couple Observational Coding Systems; Routledge: NY, New York, USA, 2004; pp. 205–222. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman, J.M. What Predicts Divorce?: The Relationship between Marital Processes and Marital Outcomes; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman, J.M. Principia Amoris: The New Science of Love; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, A.; Heavey, C.L. Interventions for couples. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1999, 50, 165–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babcock, J.C.; Waltz, J.; Jacobson, N.S.; Gottman, J.M. Power and violence: The relation between communication patterns, power discrepancies, and domestic violence. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1993, 61, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, A.; Shenk, J.L. Communication, conflict, and psychological distance in non distressed, clinic, and divorcing couples. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1991, 59, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottman, J.M. Marital Interaction: Experimental Investigations; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Betchen, S.J.; Ross, J.L. Male pursuers and female distancers in couples therapy. Sex. Relatsh. Ther. 2000, 15, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siffert, A.; Schwarz, B. Spouses’ demand and withdrawal during marital conflict in relation to their subjective well-being. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2011, 28, 262–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berns, S.B.; Jacobson, N.S.; Gottman, J.M. Demand–withdraw interaction in couples with a violent husband. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1999, 67, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornelius, T.L.; Alessi, G.; Shorey, R.C. The effectiveness of communication skills training with married couples: Does the issue discussed matter? Fam. J. 2007, 15, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrodt, P.; Witt, P.L.; Shimkowski, J.R. A meta-analytical review of the demand/withdraw pattern of interaction and its associations with individual, relational, and communicative outcomes. Commun. Monogr. 2014, 81, 28–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holley, S.R.; Haase, C.M.; Chui, I.; Bloch, L. Depression, emotion regulation, and the demand/withdraw pattern during intimate relationship conflict. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2018, 35, 408–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holley, S.R.; Sturm, V.E.; Levenson, R.W. Exploring the basis for gender differences in the demand-withdraw pattern. J. Homosex. 2010, 57, 666–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, N.R. Relationship Confidence in Newlywed Military Marriages: Relationship Confidence Partially Mediates the Link between Attachment and Communication; Brigham Young University: Provo, UT, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Markman, H.J.; Rhoades, G.K.; Stanley, S.M.; Ragan, E.P.; Whitton, S.W. The premarital communication roots of marital distress and divorce: The first five years of marriage. J. Fam. Psychol. 2010, 24, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottman, J.M. The Marriage Clinic: A Scientifically-Based Marital Therapy; WW Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman, J.M.; Gottman, J.S. Gottman Couple Therapy. The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman, J.M.; Gottman, J.S.; Cole, C.; Preciado, M. Gay, lesbian, and heterosexual couples about to begin couples therapy: An online relationship assessment of 40,681 couples. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2020, 46, 218–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor-Rodgers, E.; Batterham, P.J. Evaluation of an online psychoeducation intervention to promote mental health help seeking attitudes and intentions among young adults: Randomised controlled trial. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 168, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zarei, E.; Sanaeimanesh, M. The effect of self-disclosure skill training on communication patterns of referred couples to counseling clinics. Iran. J. Psychiatry Behav. Sci. 2014, 8, 50. [Google Scholar]

- Du Plooy, K.; De Beer, R. Effective interactions: Communication and high levels of marital satisfaction. J. Psychol. Afr. 2018, 28, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, Z.; Nikbakht Nasrabadi, A.; Behboodi Moghadam, Z.; Salehiniya, H.; Rezaei, E. A review of the factors associated with marital satisfaction. Galen Med. J. 2017, 6, 197–207. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Cao, H.; Zhou, N.; Ju, X.; Lan, J.; Zhu, Q.; Fang, X. Daily communication, conflict resolution, and marital quality in Chinese marriage: A three-wave, cross-lagged analysis. J. Fam. Psychol. 2018, 32, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, A.; Robey, P.A.; Dunham, S.M.; Dermer, S.B. Change, choice, and home: An integration of the work of Glasser and Gottman. Int. J. Choice Theory Real. Ther. 2013, 32, 36–47. [Google Scholar]

- Garanzini, S.; Yee, A.; Gottman, J.; Gottman, J.; Cole, C.; Preciado, M.; Jasculca, C. Results of Gottman method couples therapy with gay and lesbian couples. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2017, 43, 674–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baucom, B.R.; Dickenson, J.A.; Atkins, D.C.; Baucom, D.H.; Fischer, M.S.; Weusthoff, S.; Hahlweg, K.; Zimmermann, T. The interpersonal process model of demand/withdraw behavior. J. Fam. Psychol. 2015, 29, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanley, S.M.; Markman, H.J. Helping couples in the shadow of COVID-19. Fam. Process 2020, 59, 937–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davoodvandi, M.; Shokouh Navabi Nejad, V.F. Examining the effectiveness of gottman couple therapy on improving marital adjustment and couples’ intimacy. Iran. J. Psychiatry 2018, 13, 135. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| CC | TWDC | MAC | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Gend | Group | MD | SE | p | η2 | MD | SE | p | η2 | MD | SE | p | η2 | |

| Pre test | Male | Ex | Con | 0.64 | 2.22 | 0.77 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 1.39 | 0.98 | 0 | 0.94 | 1.08 | 0.38 | 0.05 |

| Fem | Ex | Con | 1.14 | 2.22 | 0.61 | 0.02 | 0.53 | 1.39 | 0.70 | 0.01 | −0.56 | 1.08 | 0.61 | 0.02 | |

| Post test | Male | Ex | Con | 7.69 | 1.75 | <0.01 | 0.17 | −2.36 | 1.41 | 0.01 | 0.21 | −2.64 | 0.92 | 0.05 | 0.27 |

| Fem | Ex | Con | 7.39 | 1.75 | <0.01 | 0.14 | −5.06 | 1.41 | <0.01 | 0.30 | 1.83 | 0.92 | 0.05 | 0.28 | |

| FU 1 | Male | Ex | Con | 7.47 | 1.62 | <0.01 | 0.13 | −3.69 | 1.58 | 0.01 | 0.04 | −2.92 | 0.89 | 0.001 | 0.07 |

| Fem | Ex | Con | 7.78 | 1.62 | <0.01 | 0.14 | −8.36 | 1.58 | <0.01 | 0.17 | −2.92 | 0.89 | 0.001 | 0.07 | |

| FU 2 | Male | Ex | Con | 9.44 | 1.73 | <0.01 | 0.18 | −5.75 | 1.72 | 0.01 | 0.07 | −3.67 | 0.86 | <0.01 | 0.11 |

| Fem | Ex | Con | 8.17 | 1.73 | <0.01 | 0.14 | −7.50 | 1.72 | <0.01 | 0.12 | −4.00 | 0.86 | <0.01 | 0.13 | |

| CC | TWDC | MAC | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Gen | Group | Mean Differences | SE | p value | η2 | Mean Differences | SE | p value | η2 | Mean Differences | SE | p value | η2 | |

| Pre test | Male | Ex | Control | 0.64 | 2.22 | 0.77 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 1.39 | 0.98 | 0 | 0.94 | 1.08 | 0.38 | 0.05 |

| Fem | Ex. | Control | 1.14 | 2.22 | 0.61 | 0.02 | 0.53 | 1.39 | 0.70 | 0.01 | −0.56 | 1.08 | 0.61 | 0.02 | |

| Post test | Male | Ex. | Control | 7.69 | 1.74 | <0.01 | 0.16 | −2.36 | 1.41 | 0.09 | 0.20 | −2.64 | 0.92 | 0.05 | 0.27 |

| Fem | Exp. | Control | 7.39 | 1.77 | <0.01 | 0.14 | −5.06 | 1.41 | <0.01 | 0.30 | 1.83 | 0.92 | 0.05 | 0.27 | |

| FU 1 | Male | Exp. | Control | 7.47 | 1.62 | <0.01 | 0.13 | −3.69 | 1.58 | 0.02 | 0.04 | −2.92 | 0.89 | 0.01 | 0.07 |

| Fem | Exp. | Control | 7.78 | 1.62 | <0.01 | 0.14 | −8.36 | 1.58 | <0.01 | 0.17 | −2.92 | 0.89 | 0.01 | 0.07 | |

| FU 2 | Male | Exp. | Control | 9.44 | 1.73 | <0.01 | 0.18 | −5.75 | 1.72 | 0.01 | 0.07 | −3.67 | 0.86 | <0.01 | 0.11 |

| Fem | Exp. | Control | 8.17 | 1.73 | <0.01 | 0.14 | −7.50 | 1.7 | <0.01 | 0.12 | −4.00 | 0.86 | <0.01 | 0.13 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Deylami, N.; Hassan, S.A.; Alareqe, N.A.; Zainudin, Z.N. Evaluation of an Online Gottman’s Psychoeducational Intervention to Improve Marital Communication among Iranian Couples. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8945. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18178945

Deylami N, Hassan SA, Alareqe NA, Zainudin ZN. Evaluation of an Online Gottman’s Psychoeducational Intervention to Improve Marital Communication among Iranian Couples. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(17):8945. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18178945

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeylami, Neda, Siti Aishah Hassan, Naser Abdulhafeeth Alareqe, and Zaida Nor Zainudin. 2021. "Evaluation of an Online Gottman’s Psychoeducational Intervention to Improve Marital Communication among Iranian Couples" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 17: 8945. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18178945

APA StyleDeylami, N., Hassan, S. A., Alareqe, N. A., & Zainudin, Z. N. (2021). Evaluation of an Online Gottman’s Psychoeducational Intervention to Improve Marital Communication among Iranian Couples. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(17), 8945. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18178945