Mental and Physical Health Problems as Conditions of Ex-Prisoner Re-Entry

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Health Care during Imprisonment

Interviewee (I): I actually came here [to the therapeutic ward] under duress, because I did not agree to the therapy myself, because I did not want to. The psychologist referred me to the penitentiary court, they stated in article 117 that I must go to treatment, because I have a problem, I’m addicted, right? I denied it (…) I did nothing, I didn’t participate [in therapy]. I fucked this whole thing. I stood by my own, that I have no problem with drugs, that I can handle it. (…) They are sick, they want to put some disease in my head. Which I don’t really have. (…) So, when I was here on the ward, I endured drugs. My brother used to visit me from freedom to see me, he brought me heroin, amphetamines, needles, syringes. <adult male, recidivist>

I: When they are in the transition room, they go through this withdrawal period and then they end up in the [support] group and that’s it. And later, if an addiction is diagnosed (…) he may go to a correctional facility in Białystok, and that is that. There are simply no specialists at the shelter who would do it properly. <counselor, juvenile facility>

I: You cannot even ask for a visit to the doctor, because the waiting time is 3 weeks, for an antibiotic—4 months. So, either you will manage to heal yourself or—as I had it—the disease will spread to the whole body, because I have a [skin disease] and I needed such a specific medicine (…) and I got to the doctor after 4 months. It was during this time that it developed all over my skin, everywhere. <adult male, 1st time prisoner>

I: Doctors disregard us (…) Healthcare here is at a zero level. Polopyrine here is [a cure] for everything. The girl from my cell got it, for example, for inflammation of the peritoneum. <adult female, 1st time prisoner>

I: It’s horrific here… You can die here. When I was in [Name of the prison], a girl arrived (…) from this prison. And she had in her papers that she simulated a heart defect, because that was what the local doctors said, so they didn’t accept her there either. And she died on the same night she arrived. <adult female, 1st time prisoner>

Researcher (R): And what is your favorite way of spending your time in prison?

Interviewee (I): I used to go to a psychiatrist to prescribe me sleeping pills. Because my thoughts are so weird. [The doctor] didn’t ask about it, he did not research, he just would rewrite the prescription. Sometimes I collected these [pills] from others so I could sleep all the time. <adult male, recidivist>

I: They [inmates from a hostile subculture group] beat me up so much that they took me unconscious to the [prison] hospital. (…) I will never forget this. They did something to my leg, it started to crush me (…) but when I wanted to go to the doctor they said I was simulating, because the leg is not swollen. However the pain was horrendous. I could not put my foot gently or even rest without pain. When I finally went to the doctor I had a fever of 40 degrees. <adult male, recidivist>

I: Especially mental health protection is a big problem, because someone calculated up there that the cost was 12–13 thousand [PLN]. The salary of a psychiatrist is quite a lot and they dismissed a psychiatrist treating prisoners. They offered him a lump sum and he refused as the rates were ridiculous. And the problem of the situation of people with disorders leaving prisons emerged. They then go outside and pose a threat to themselves and others. <Prison Service informer>

I: Boys very often come to the facility with a diagnosis of a personality disorder, while the literature says that personality is formed until the age of 18–19, so a boy may reveal features only, this personality may only develop, but it irritates me when I see a diagnosis of a borderline personality disorder in a 15-year-old. Often, psychiatrists write a personality disorder, yet they combine it with ADHD and the matter is over the top. (…) And they usually already have labels attached to their documents. <psychologist, juvenile facility>

R: Why did you cut your hands?

I: Because I had such a period, because of various problems… For example, my mother turned against me when she was with her boyfriend, it was also because of this. <female, juvenile facility>

R: I noticed that this [cutting hands] is probably such a fashion. One day, only one girl has her arms cut, another one it’s several…

I: Because some [girls] are so cool and all. I know this one… she thinks it’s cool and that she likes to cut her hands, because it looks fancy. And she had such a cut, ugly, I wouldn’t be able to cut it this way to make it look asymmetrical somehow. <psychologist, juvenile facility>

I: I told myself that I would not be held responsible and that I would not be in prison for so many years… I would cut my wrists as soon as I step into detention. After they locked me up, I slashed my veins on the second day. I was lying in this bed, I took out the artery (…) About three hours I was bleeding out (…) I was getting cold, I was getting hot, I started to sweat (…) I reached out for cigarettes and lost consciousness. <adult male, recidivist>

I: When I got imprisoned (…) I had so many eschars [caused by self-injecting with heroin] that they had nowhere to insert the needle… legs and hands (…) They had to put cannulas in my neck (…) [With three other people] I took a kilo of mephedrone and almost a kilo of heroin over the span of three months. It scares me terribly and I thank God that I am actually in prison. <adult male, recidivist>

3.2. Health Issues as Barriers to Re-Entry

I: The fact that [a prisoner] was serving a sentence does not mean that he does not come back [to the therapy ward]. He does. I am working in a substitutive therapy unit, i.e., where an addicted patient takes methadone. He comes back anyway. Despite our efforts. So my activity is mainly limited to helping him find himself in the society, again and again. <psychotherapist, prison therapy ward>

I: One thing is worth noting: the fact that they do not have access to drugs in the facility does not mean that they are already clean. They declare that as soon as they leave, they will “pull in their nose”. <psychotherapist, juvenile facility>

I: I was waiting for this day of departure, you know it! (…) And the closer to this exit, the more I was overwhelmed … Well, to put it so brutally, I had terrible poops. I didn’t want this previous life anymore, but I was afraid. <adult male, ex-prisoner, recidivist>

I: Most often, these people go to the same places, to the same people (…) with their old habits (…) while in statistics about 70% of crimes [are those committed] under the influence of alcohol. (…) Human pro-health behaviors outside prison are absolutely crucial if you don’t want to come back here. But when funds run out, you have to find a way to get them, and under the influence of alcohol it is easier not to worry that the crime will be exposed. This is most often the case of robberies and the circle is closed. <counselor, adult male prison facility>

I: (…) so I‘m leaving prison. I lost my apartment [while serving a 15-year sentence], I don’t have anywhere to go. I got, I think, 150 PLN, which is actually a maximum for what they give you (…) I got some clothes there, but you can probably imagine their quality (…) So where will I sleep? I spend the first night at my friend’s, the second at another’s apartment. And that’s it. That’s the help you receive. And now, how do you survive? Even if you tried I don’t know how hard, you won’t be able to live on. <adult male, ex-prisoner, recidivist>

I: There was a boy who came out of here, mentally ill, came out of here and stood in the gate and didn’t know what to do with himself. Then he started walking across the field, into the trees and back to the gate. He didn’t know where to go, what to do. The ambulance had to come, and they asked what was wrong with him. They took him to the counselor, and the counselor just said that the boy was mentally ill. So they took him to the hospital. <adult male, recidivist>

I: Prisoners after larger sentences, such as few years old, I think they are more closed and withdrawn (…) They are often so damaged and so personality disturbed after being released from prison that they need a longer, deeper, and more intense work on themselves. <prison psychologist>

I: Access to free psychological care is crucial (…) so that in a difficult, mutagenic situation of relapse, this person could quickly contact a specialist who would help him and prevent a mishap (…) or relapse. As far as I know, the waiting period for a psychological consultation under the National Health Fund is about 12 months and 2–3 months to see a psychiatrist. (…) Some of them can afford private medical advice but most are unable to pay for such benefits, it’s difficult to find a job and cope with the life outside prison, and even more so in paying for medical advice, which is not the cheapest. <prison psychologist>

I: Let’s be clear about this. Depriving someone of physical freedom is violence. (…) A person who experiences violence learns to miss it. These people miss this system. These mechanisms are like hypocrisy in any addiction. A man will subconsciously do everything to get there once again. <therapist>

I: Why can’t I find a job? I tried, I really tried (…) but now I’m constantly unemployed. (…) when I went to the a commission [for assessing the degree of disability], they told me “You speak rather well, you hear a little, you are capable, you can go to work”. Really? I am? So why doesn’t anyone want to hire me? <adult male, ex-prisoner>

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Wickramasekera, N.; Wright, J.; Elsey, H.; Murray, J.; Tubeuf, S. Cost of Crime: A systematic review. J. Crim. Justice 2015, 43, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, E.; Ellis, C.A. Impact of Crime on Victims. National Victim Assistance Academy Track 1: Foundation-Level Training; 2010; Chapter 6; Available online: https://www.coursehero.com/file/34406527/E075Materialsdoc/ (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Shapland, J.; Hall, M. What do we know about the effects of crime on victims? Int. Rev. Victimol. 2007, 14, 175–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haney, C. The Psychological Impact of Incarceration: Implications for Post-Prison Adjustment. In Proceedings of the National Policy Conference: From Prison to Home, The Effect of Incarceration and Reentry on Children, Families and Communities, Washington, DC, USA, 30–31 January 2002; Available online: https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/psychological-impact-incarceration-implications-post-prison (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Heeks, M.; Reed, S.; Tafsiri, M.; Prince, S. The Economic and Social Costs of Crime, 2nd ed.; Research Report 99; Home Office: London, UK, 2018. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-economic-and-social-costs-of-crime (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Jaitman, L.; Torre, I. The Costs of Imprisonment. In The Costs of Crime and Violence. New Evidence and Insights in Latin America and the Caribbean; Jaitman, L., Ed.; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fair Society, Healthy Lives. Strategic Review of Health Inequalities, The Marmot Review. 2010. Available online: https://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/fair-society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review/fair-society-healthy-lives-full-report-pdf.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Murray, J.; Farrington, D.P.; Sekol, I.; Olsen, R.F. Effects of parental imprisonment on child antisocial behavior and mental health: A systematic review. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2009, 4, 1–105. [Google Scholar]

- Travis, J.; Solomon, A.L.; Waul, M. From prison to home. In The Dimensions and Consequences of Prisoner Re-Entry; Urban Institute Justice Policy Centre: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Petersilia, J. Prisoner Reentry: Public Safety and Reintegration Challenges. Prison J. 2001, 81, 360–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, P.; O’Donovan, D.; Elmusharafl, K. Measuring social exclusion in healthcare settings: A scoping review. Int. J. Equity Health 2018, 17, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, A.D.; Kinner, S.A.; Young, J.T. Social Environment and Hospitalisation after Release from Prison: A Prospective Cohort Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörmansdörfer, C. Health and Social Protection. In “Promoting Pro-Poor Growth”; Social Protection; OECD: Paris, France, 2009; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/greengrowth/green-development/43514554.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- House of Commons. Prison Health, Health and Social Care Committee. Twelfth Report of Session 2017–19; House of Commons: London, UK, 2018; Available online: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmhealth/963/963.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Haglund, A.; Tidemalm, D.; Jokinen, J.; Långström, N.; Lichtenstein, P.; Fazel, S.; Runeson, B. Suicide after release from prison: A population-based cohort study from Sweden. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2014, 75, 1047–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalev, S. A Sourcebook on Solitary Confinement; Mannheim Centre for Criminology: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, A. Primary health care in prisons. In Health in Prisons. A WHO Guide to the Essentials in Prison Health; Møller, L., Stöver, H., Jürgens, R., Gatherer, A., Nikogosian, H., Eds.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, T. Social exclusion. In The SAGE Dictionary of Criminology; McLaughlin, E., Muncie, J., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sykes, G. The Society of Captives: A Study of a Maximum Security Prison; Revised Edition with a new Introduction by Bruce Western; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 63–83. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, R.G.; Worrall, J.L. Prison Architecture and Inmate Misconduct: A Multilevel Assessment. Crime Delinq. 2010, 60, 1083–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomczyński, P. Infrastrukturalne uwarunkowania i rezultaty kontroli sprawowanej przez personel wobec wychowanków zakładów poprawczych i schronisk dla nieletnich. Kult. Społecz. 2016, 60, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miszewski, K. Adaptacja do Warunków Więziennych Skazanych Długoterminowych, Praca Doktorska, Uniwersytet Warszawski, Warszawa, Napisana pod Kierunkiem Prof. dra hab; Andrzeja, R., Ed.; ISNS UW: Warszawa, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zweig, J.M.; Naser, R.L.; Blackmore, J.; Schaffer, M. Addressing Sexual Violence in Prisons: A National Snapshot of Approaches and Highlights of Innovative Strategies. Final Report; Urban Institute, Justice Policy Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; Available online: https://www.urban.org/research/publication/addressing-sexual-violence-prisons (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Hensley, C. Consensual Homosexual Activity in Male Prisons. Correct. Compend. 2001, 26, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Miszewski, K.; Kacprzak, A. Zachowania seksualne mężczyzn w zakładach karnych i ich postrzeganie. Przegląd badań i analiz przeprowadzonych w więzieniach USA. In Przemoc Seksualna. Interdyscyplinarne Studium Zjawiska; Gardian-Miałkowska, R., Ed.; Oficyna Wydawnicza Impuls: Kraków, Poland, 2021; pp. 141–163. [Google Scholar]

- Blaauw, E.; Van Marle, H.J.C. Mental health in prisons. In Health in Prisons. A WHO Guide to the Essentials in Prison Health; Møller, L., Stöver, H., Jürgens, R., Gatherer, A., Nikogosian, H., Eds.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Social Exclusion Unit. Reducing Re-Offending by Ex-Prisoners; Office of the Deputy Prime Minister: London, UK, 2002.

- Spaulding, A.C.; Eldridge, G.D.; Chico, C.E.; Morisseau, N.; Drobeniuc, A.; Fils-Aime, R.; Day, C.; Hopkins, R.; Jin, X.; Chen, J.; et al. Smoking in correctional settings worldwide: Prevalence, bans, and interventions. Epidemiol. Rev. 2018, 40, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valera, P.; Acuna, N.; Vento, I. The Preliminary Efficacy and Feasibility of Group-Based Smoking Cessation Treatment Program for Incarcerated Smokers. Am. J. Men’s Health 2020, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Audit Office. Mental Health in Prisons. Her Majesty’s Prison & Probation Service, NHS England and Public Health England. 2017. Available online: https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Mental-health-in-prisons.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2021).

- Rebalancing Act. Revolving Doors Agency, Public Health England, Home Office. 2017. Available online: http://www.revolving-doors.org.uk/file/2049/download?token=4WZPsE8I (accessed on 28 June 2021).

- Bronson, J.; Stroop, J.; Zimmer, S.; Berzofsky, M. Drug Use, Dependence, and Abuse among State Prisoners and Jail Inmates, 2007–2009; U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. Available online: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/dudaspji0709.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Kiryluk, M. Opinie Lekarzy Więziennych o Problemach Zdrowotnych Osób Pozbawionych Wolności. Biuletyn Rzecznika Praw Obywatelskich: Warszawa, Poland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Szymanowska, A. Więzienie i co Dalej? Wydawnictwo Akademickie Żak”: Warszawa, Poland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Szymanowski, T. Prawo Karne Wykonawcze; Wolters Kluwer Polska: Warszawa, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pindel, E. W kierunku efektywności oddziaływań penitencjarnych. Resocjalizacja w polskich zakładach karnych. Probacja 2009, 2, 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Supreme Chamber of Control [Najwyższa Izba Kontroli]. Readaptacja Społeczna Skazanych na Wieloletnie Kary Pozbawienia Wolności, Informacja o Wynikach Kontroli. Departament Porządku i Bezpieczeństwa Wewnętrznego. 2015. Available online: https://www.nik.gov.pl/plik/id,9730,vp,12100.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Ministerstwo Sprawiedliwości. Annual Statistical Information for 2019/2020 [pl. Roczna Informacja Statystyczna za rok 2020]; Ministerstwo Sprawiedliwości, Centralny Zarząd Służby Więziennej: Warszawa, Poland, 2020. Available online: http://sw.gov.pl/Data/Files/001c169lidz/rok-2013.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Campbell, K.C. Rehabilitation Theory. In Encyclopedia of Prisons & Correctional Facilities Bosworth; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, G.; Crow, I. Offender Rahabilitation. In Theory, Research and Practice; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- AVERT. Prisoners, HIV and AIDS. 2019. Available online: https://www.avert.org/printpdf/node/385 (accessed on 29 June 2021).

- Stępniak, P. Prawo do świadczeń zdrowotnych w warunkach izolacji penitencjarnej. In Monografie Prawnicze; Wyd. C.H.Beck: Warszawa, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

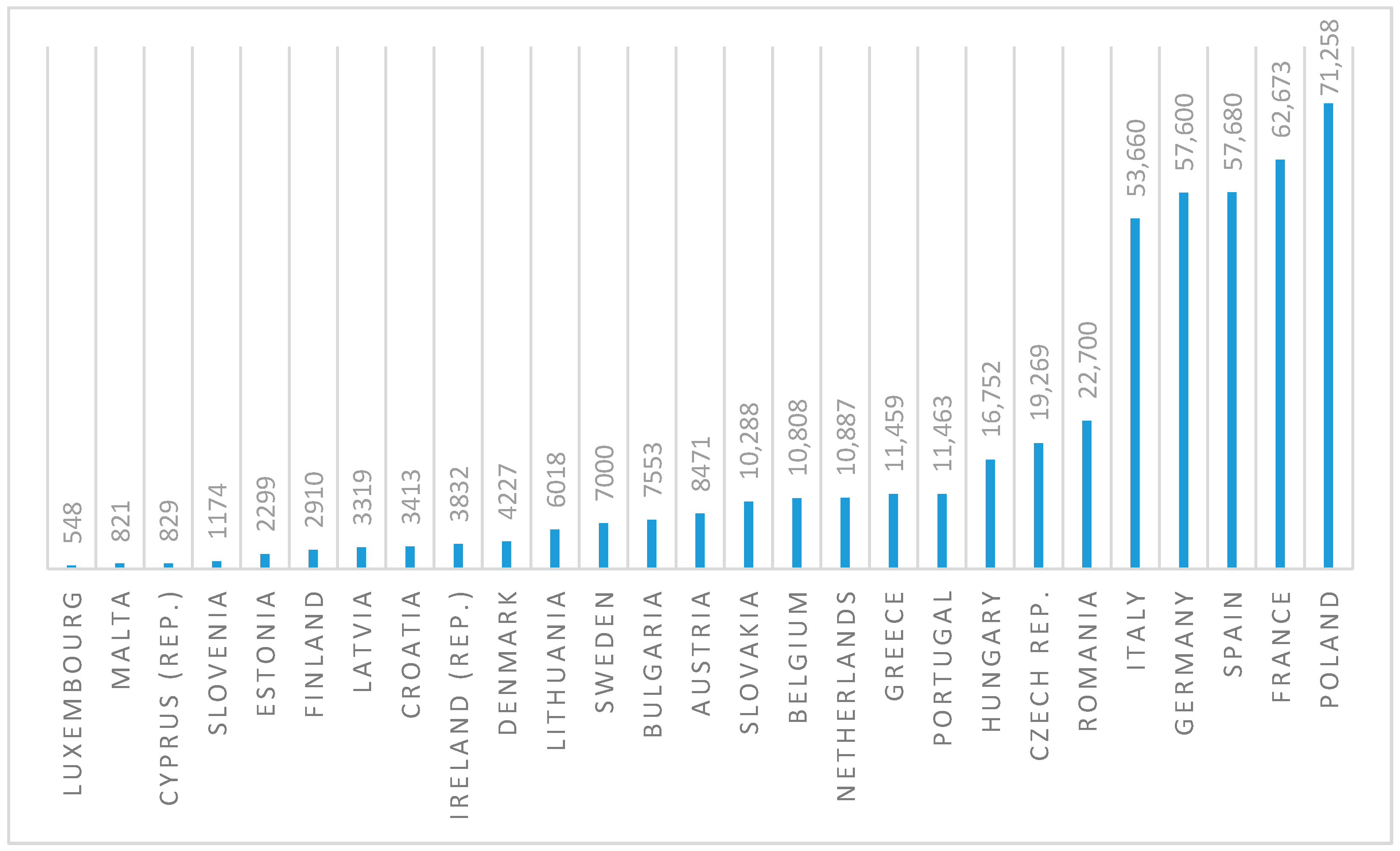

- Available online: https://www.prisonstudies.org/map/europe (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- Available online: https://www.sw.gov.pl/strona/statystyka-roczna (accessed on 23 June 2021).

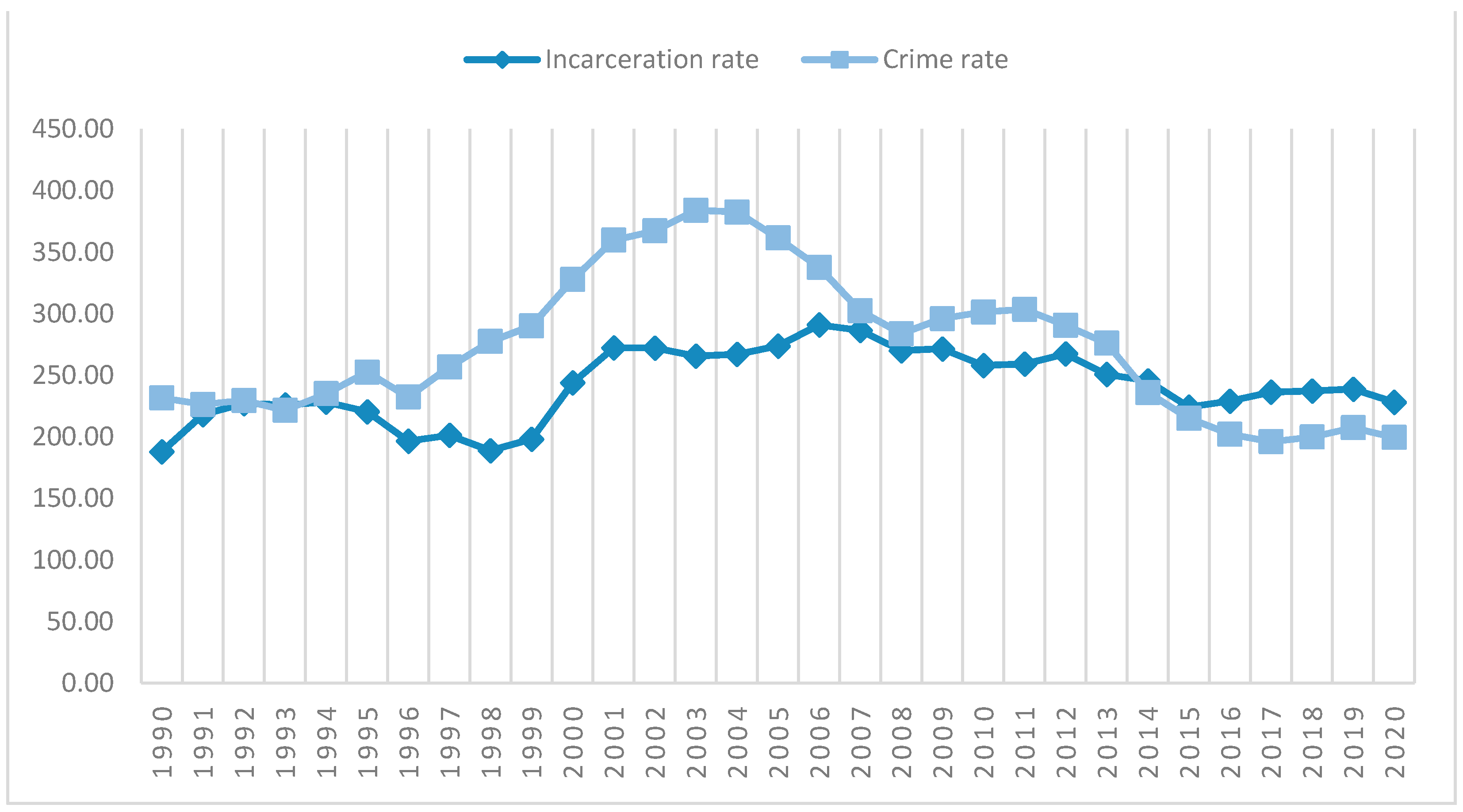

- Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/en/ (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- Available online: https://statystyka.policja.pl/ (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- Stępniak, P. Resocjalizacja (nie)urojona. In O Zawłaszczaniu Przestrzeni Penitencjarnej; Difin SA: Warszawa, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jaworska, A. Zasoby Osobiste i Społęczne Skazanych w Procesie Oddziaływań Penitencjarnych; Impuls: Kraków, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bałandynowicz, A. Probacyjna Sprawiedliwość Karząca; Wolters Kluwer Polska: Warszawa, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Szymanowski, T. Przestępczość i Polityka Karna w Polsce: W Świetle Faktów i Opinii Społeczeństwa w Okresie Transformacji; Wolters Kluwer: Warszawa, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chomczyński, P.; Pyżalski, J.; Kacprzak, A. Społeczne Uwarunkowania Zjawiska Przestępczości Nieletnich i Dorosłych [Social Determinants of Juvenile and Adult Crime]; Ministry of Justice: Warsaw, Poland, 2018. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/39145993/Raport_pt_Spo%C5%82eczne_uwarunkowania_zjawiska_przest%C4%99pczo%C5%9Bci_nieletnich (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Noaks, L.; Wincup, E. Criminological Research: Understanding Qualitative Methods, 1st ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomczyński, P. Doing Ethnography in a Hostile Environment: The Case of a Mexico Community. Research Method Cases; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chomczyński, P.A.; Guy, R. ‘Our biographies are the same’: Juvenile Work in Mexican Drug Trafficking Organizations from the Perspective of a Collective Trajectory. Br. J. Criminol. 2021, 61, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, B.; Kitzinger, J.; Kitzinger, C. Anonymising interview data: Challenges and compromise in practice. Qual. Res. 2014, 15, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kacprzak, A. Resocjalizacja i pomoc postpenitencjarna w Polsce oczami skazanych kobiet i mężczyzn—Wnioski z badań jakościowych. In Wybrane Problemy Społeczne Współczesnej Polski; Szukalski, P., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego: Łódź, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fleetwood, J. In Search for Respectability. Narrative Practice in a Women’s Prison in Quito, Ecuador. In Narrative Criminology, 1st ed.; Presser, L., Sandberg, S., Eds.; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 42–68. [Google Scholar]

- Crewe, B. Process and Insight in Prison Ethnography. In Doing Ethnography in Criminology; Rice, S.K., Maltz, M.D., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K. The Research Act: A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978; pp. 297–331. [Google Scholar]

- Hammersley, M.; Atkinson, P. Ethnography: Principles in Practice, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 63–96. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine Publishing: London, UK, 1967; pp. 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.L.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques, 1st ed.; Sage: London, UK, 1990; pp. 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Konopásek, Z. ‘Making Thinking Visible with Atlas.ti: Computer Assisted Qualitative Analysis as Textual Practices’. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2008, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Results from the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs, European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. Espad. 2020. Available online: http://www.espad.org/espad-report-2019 (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Chomczyński, P. Działania wychowanków schronisk dla nieletnich i zakładów poprawczych. In Socjologiczna Analiza Interakcji Grupowych; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego: Łódź, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chomczyński, P.A. Emotion Work in the Context of the Resocialization of Youth in Correctional Facilities in Poland. Pol. Sociol. Rev. 2017, 2, 219–236. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, E. Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patient and Other Inmates; Anchor Books: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Makkai, T.; Payne, J. Drugs and Crime: A Study of Incarcerated Male Offenders; Australian Institute of Criminology Research and Public Policy: Melbourne, Australia, 2005; Series No. 52. [Google Scholar]

- Stępniak, P. Sytuacja zdrowotna i ochrona zdrowia więźniów w zakładach karnych, Archiwum Kryminologii, Tom XXXV. Arch. Criminol. 2013, 333–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fransson, E.; Giofrè, F.; Johnsen, B. (Eds.) Prison, Architecture and Humans; Cappelen Damm Akademisk/NOASP: Oslo, Norway, 2018; Available online: https://press.nordicopenaccess.no/index.php/noasp/catalog/book/31 (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Szczygieł, B. Społeczna Readaptacja Skazanych w Polskim Systemie Penitencjarnym; Temida 2: Białystok, Poland, 2002; pp. 138–139. [Google Scholar]

- Kinner, S.A. The Post-Release Experience of Prisoners in Queensland, Canberra; Australian Institute of Criminology: Melbourne, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pobal; Network of Ex-Prisoner Voluntary Agencies. Social Inclusion of ex-prisoners and their families: The role of Partnership. In Report on Seminars Organized by NEVA and Pobal in 2007; Pobal Supporting Communities: Dublin, Ireland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Clemmer, D. The Prison Community; Christopher Publishing House: Hanover, MA, USA, 1940. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, K.E.; Tangey, J.P.; Stuewig, J.B. The Self-Stigma Process in Criminal Offenders. Stigma Health 2016, 1, 206–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, D.M.; Chaudoir, S.R. Living with a conceable stigmatized identity: The impact of anticipated stigma, centrality, salience, and cultural stigma on psychological distress and health. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 97, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamoto, D.K.; Gordon, D.; Oliveros, A.; Perez-Cabello, A.; Brabham, T.; Lanza, S.; Dyson, W. The Role of Masculine Norms and Informal Support on Mental Health in Incarcerated Men. Psychol. Men Masc. 2012, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, M.; Deess, P.; Allen, C. The First Month out. Post-Incarceration Experiences in New York City. Vera Inst. Justice 2011, 24, 72–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowen, T.J.; Visher, C.A. Drug Use and Crime after Incarceration: The Role of Family Support and Family Conflict. Justice Q. 2015, 32, 337–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haney, C. The Psychological Impact of Incarceration. Implications for Postprison Adjustments. In Prisoners Once Removed: The Impact of Incarceration and Reentry on Children, Families and Communities; Waul, T., Ed.; The Urban University Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Visher, C.A.; Yang, Y.; Mitchell, S.G.; Patterson, Y.; Swan, H.; Pankow, J. Understanding the sustainability of implementing HIV services in criminal justice settings. Health Justice 2015, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidelus, A. Determinanty Readaptacji Społecznej Skazanych; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Kardynała Stefana Wyszyńskiego: Warszawa, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett, R. To re-offend or not to re-offend? The ambivalence of convicted property offenders. In After Crime and Punishment. Pathways to Desistance from Crime; Immarigeon, M., Ed.; Willan: Cullompton, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Uggen, C.; Manza, J.; Behrens, A. ‘Less than the average citizen’: Stigma, role transition and the civic reintegration of convicted felons. In After Crime and Punishment. Pathways to Offender Reintegration; Immarigeon, M., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- McHardy, F. Out of Jail but Still not Free: Experiences of Temporary Accommodation on Leaving Prison; EPIC/The Poverty Alliance: Glasgow, Scotland, 2010; Available online: https://www.poverty.ac.uk/system/files/attachments/EPIC%20Research_Out%20of%20Jail%20but%20still%20not%20free.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Houchin, R. Social Exclusion and Imprisonment in Scotland; Glasgow Caledonian University: Glasgow, Scotland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Maruna, S. Making good. How Ex-Convicts Reform Their and Rebuild Their Lives; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, L.N.; Lanza, A.; Dyson, W.; Gordon, D. The Role of Prevention in Promoting Continuity of Health Care in Prisoner Reentry Initiatives. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 830–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornblum, W.; Julian, J. Social Problems, 14th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, T.; Maruna, S. Rehabilitation. In Beyond the Risk Paradigm; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wysocka, E. Diagnoza Pozytywna w Resocjalizacji. In Model Teoretyczny i Metodologiczny; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego: Katowice, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Granosik, M.; Gulczyńska, A.; Szczepanik, R. Przekształcanie Klimatu Społecznego Ośrodków Wychowawczych dla Młodzieży Nieprzystosowanej Społecznie (MOS i MOW), Czyli o Potrzebie Rozwoju Dyskursu Profesjonalnego Oraz Działań Upełnomocniających; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego: Łódź, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pękala-Wojciechowska, A.; Kacprzak, A.; Pękala, K.; Chomczyńska, M.; Chomczyński, P.; Marczak, M.; Kozłowski, R.; Timler, D.; Lipert, A.; Ogonowska, A.; et al. Mental and Physical Health Problems as Conditions of Ex-Prisoner Re-Entry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7642. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147642

Pękala-Wojciechowska A, Kacprzak A, Pękala K, Chomczyńska M, Chomczyński P, Marczak M, Kozłowski R, Timler D, Lipert A, Ogonowska A, et al. Mental and Physical Health Problems as Conditions of Ex-Prisoner Re-Entry. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(14):7642. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147642

Chicago/Turabian StylePękala-Wojciechowska, Anna, Andrzej Kacprzak, Krzysztof Pękala, Marta Chomczyńska, Piotr Chomczyński, Michał Marczak, Remigiusz Kozłowski, Dariusz Timler, Anna Lipert, Agnieszka Ogonowska, and et al. 2021. "Mental and Physical Health Problems as Conditions of Ex-Prisoner Re-Entry" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 14: 7642. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147642

APA StylePękala-Wojciechowska, A., Kacprzak, A., Pękala, K., Chomczyńska, M., Chomczyński, P., Marczak, M., Kozłowski, R., Timler, D., Lipert, A., Ogonowska, A., & Rasmus, P. (2021). Mental and Physical Health Problems as Conditions of Ex-Prisoner Re-Entry. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(14), 7642. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147642