“If It Goes Horribly Wrong the Whole World Descends on You”: The Influence of Fear, Vulnerability, and Powerlessness on Police Officers’ Response to Victims of Head Injury in Domestic Violence

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Domestic Violence and Health

1.2. Police Attitudes toward DV

1.3. Attitude Theory

1.4. Impact of Austerity on Policing DV

1.5. Present Study

- How do police officers construct attitudes towards victims of DV?

- How do police interpret and respond to stories of head trauma or symptoms of BI with victims of DV?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Sample

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Analysis

2.5. Credibility Checks

2.6. Researcher Reflexivity

3. Results

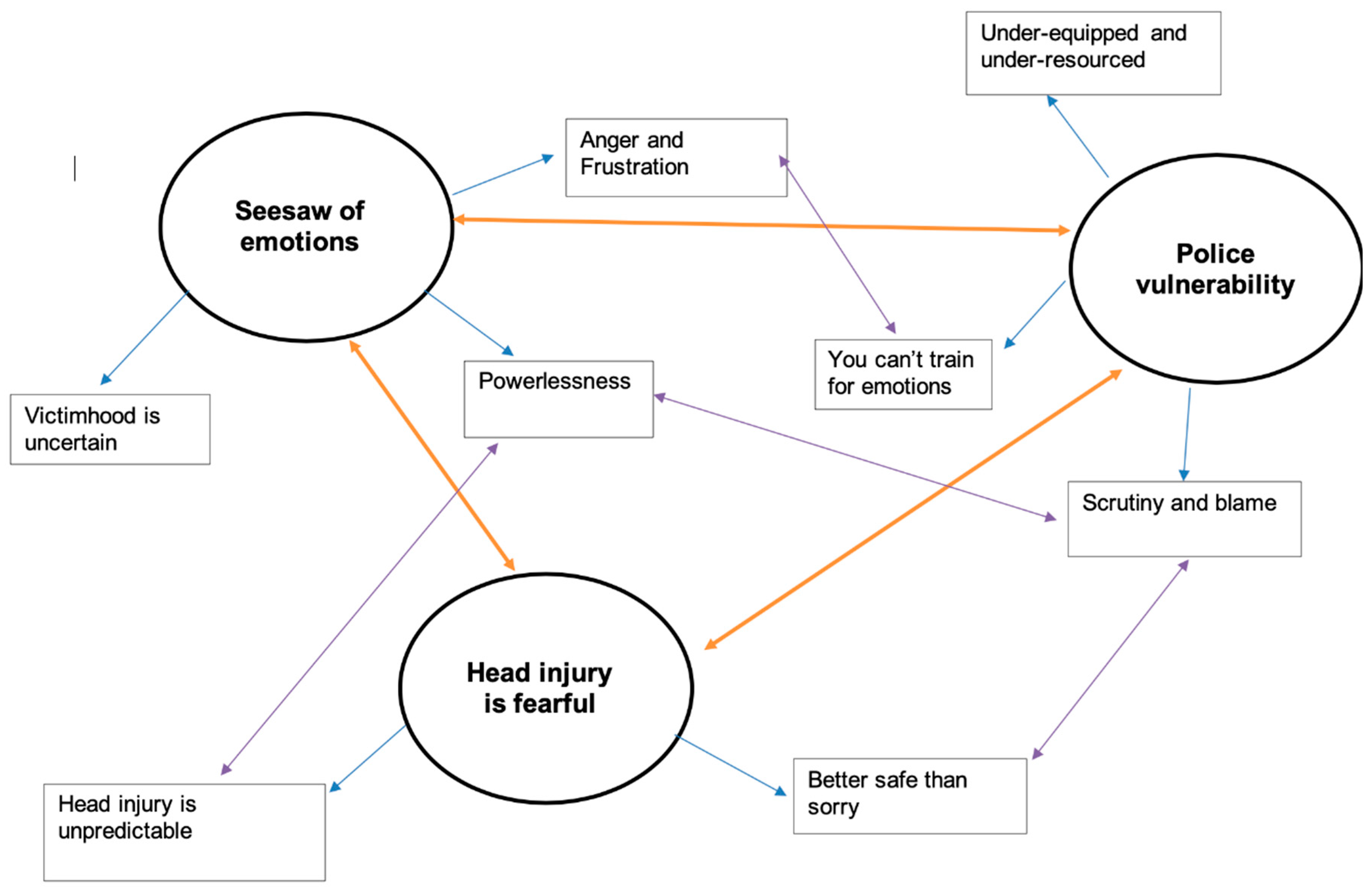

3.1. Global Theme 1: Seesaw of Emotions

I’d probably say at least 75% we go, arrest the offender, male or female, and then they don’t want to press any charges or make a formal complaint, give us a statement, support the prosecution.(Rachel)

There’s only so much I can do as a police officer, which is hard because I want to do more sometimes. But I can’t make you leave that abusive partner. As much as you will sit there... I’ve sat there for hours with victims trying to get them to make that first step. Sometimes they’re the one who’s got to make that leap.(Ian)

We are not the organisation that people want to see because we are of no help to them whatsoever. We can’t direct refer, we can’t offer any clinical advice, we can’t offer any help whatsoever.(Liam)

You don’t have any training as a police officer to actually speak to someone that might be suffering a crisis. (Paul) Unfortunately, with the police officers, it’s a lot of putting a plaster on at times. We can deal with fixing the short-term.(Thomas)

It gets frustrating, because you feel like, “We’ve done our best to help you, and you’re still at risk, and it looks as though you’re putting yourself at risk.”(Jack)

I don’t get it, if I’m honest. I get a lot of things in policing; I understand why people steal things, I understand why people potentially become sex offenders—I can see the mind-set, and why people get caught up in that. I struggle with domestic violence, because on a personal level, I just don’t get it really.(Ian)

They stay for years, some of them. I understand it is really difficult for them to break free, but I can’t process why it is that difficult for them to break free.(Will)

I think it is sad in a certain extent. I think there are occasions when things are really bad where you think, I can’t think logically as to why that person would do that. Sometimes you get frustrated with that person, particularly when you are trying to help them and they don’t want to help themselves.(Liam)

Our job is to be impartial, it’s not to be judge jury and executioner… My feelings towards D… DV perpetrators myself. I hate them. I think they’re horrible people, men and women alike… My thoughts to people I nick for domestic violence. I don’t get emotionally involved because that’s not my job.

It’s frustrating when you walk into addresses and you’ll see the same people who have injuries, and you look at the bloke or the female and they’re almost cocky with it. ‘What are you going to do?’ And you just think, if I could just have five minutes, I’d kick seven bells of shit out of you, and see how you like it.(Ian)

With quite a lot of domestics, you feel like a taxi service.(Paul)

A vast majority of our calls are domestic related. And obviously, the ones that stick out in your brain are the ones that usually are significant because something horrific has happened. But actually, I’ve been to equally many that weren’t horrific, but you don’t remember all the details and all the things of those because you are going to several a day.(Emily)

It can just be really mundane, and it’s like, “Yes, you’ve had an argument, okay, here’s the process,” and you’re not thinking, you’re not challenged, and you’re just like, oh, it’s just process. No, I don’t like them.(Jack)

You know that there is an amount of paperwork that goes with that so there is always an amount of mundanity to it if it is relatively routine.(Liam)

Just by chance, two years ago I was doing just a traffic job up on X Street. She came out of the shop and said, “I remember you,” told me all about it, and just said, “I’m just so glad that I had the courage to come down and talk to you that night, and the police supported me through everything.” And that was like, well, if that’s just one person, great.(David)

There is no not genuine victim ever—but it’s the ones where it’s messier and harder to work out who’s more to blame, or who’s not to blame, or what’s gone on(Emily)

There is a blame culture but there’s also empathy you know, and we do feel genuinely sorry for people. We do feel genuinely worried for people. We also feel very worried for people who actually aren’t willing to help themselves. There’s some people who you just know you can help that night and you know tomorrow there gunna have them back and they’re going to have the living crap beaten out of them next week.(Ben)

You do get different jobs where you can see which one is a genuine victim and you feel sorry for, and you’ve got to try and not feel sorry for and just help them.(Jack)

Sometimes I think there are occasions where you have victims that may well be offenders on different days or may well play up to stuff and use what they know will happen to domestic abuse suspects to make up allegations.(Liam)

A lot of the time it’s because between couples, they use us, they know that they can ring the police and if we turn up and they say, “I want them out of my house,” then it’s as if we are there like security guards kind of thing and we do get used for that quite a lot(Rachel)

Sometimes, arresting people just because it is a domestic doesn’t necessarily mean it’s the right thing to do. It might be the first time that anything’s ever happened between them, and someone’s lost their temper because of some trivial matter and someone’s ended up getting hurt, which isn’t right, but it doesn’t mean that by taking away their liberty and arresting them.(Paul)

You get sometimes people who are highly dysfunctional. One of the big taboos about domestic violence is mutually abusive relationships, and they do happen, where you get… it sounds almost dismissive to say they’re both as bad as each other, and it’s not meant to, but unfortunately there are situations which are like that.(Michael)

It’s going to sounds terrible to say but um its true, um, but there is a real victim and a victim for the sake of being a victim. So, we have our real victims, the ones that suffer in silence. The ones that suffer abuse day in day out for a period of time. That hide it from their family, that hide injuries, that hide psychological injuries, who eventually have the bravery to come forward or approach someone and want our help.(Ben)

Most of them are. I’d say most are around drugs and alcohol.(Rachel)

Um… but a lot are (sighs) you know I think a lot what we classify as domestic abuse is very closely intertwined with mental health, substance abuse and history of abuse themselves.(Ben)

Stereotyping a bit, but generally it is male perpetrators against women.(Will)

Most of the stuff, to be fair, that I go to is arguments and it’s women who may have an injury to an eye, a black eye.(Peter)

Anyone who’s been a police officer longer than five minutes knows it’s a mistake to automatically assume that the man’s the aggressor and the woman’s the victim.(Michael)

It might be that they can’t actually leave each other. It might be that they’ve tried to leave and it made it even more violent, or they have left and they’ve found them again, or they’ve left and they just can’t cope being on their own. Some people have got poor mental health, and it might not be like mental health in terms of an actual illness, but it might be low confidence, anxiety; they can’t be on their own. Sometimes you go to the same people, but it’s a different partner, but they’re still being offended against. And it’s difficult to understand why; if you’ve removed the offender and you’re no longer with him or her, and you’re in a new relationship, why is this still continuing?(Jack)

A lot of people see that as a trouble when they go to the incidents in the first place, especially if it’s a recurrent address they’re going to and you know what the result will be before you get there, where they’re likely to not talk to you, not provide a statement, and if you arrest this person and take them away, they’ll just be coming back a few hours later and probably doing the same thing again. And a lot of people, they can’t help themselves; the police will just try and help them and help them, but if they don’t want the help, it’s not going to help them.(Paul)

The problem is, you don’t always have time to do it, and there’s a lot of supervisors who won’t prioritise having that conversation. I did, because it was something I was passionate about, and I hated hearing that black humour; I hated hearing that desensitisation and those coping strategies. I understood them all, but I just didn’t like them. So, I would have those conversations. But actually, like I say, I had to be very sensitive and careful what times, because you could feel your staff withdrawing, “Oh god” and rolling their eyes, “not that conversation again”.

3.2. Global Theme 2: Police Vulnerability

We are dealing with so much more—for instance, mental health—we are dealing with so much more of that now than we did even ten years ago, because those services have been stripped back. And we don’t want to end up in a situation where basically, and this is already going a lot, where police are picking up the shortfall of other departments.(Michael)

Sometimes we are paramedics, stabbings, shootings, whatever else that we go to, mental health, like I say, paramedics, psychiatrists, going out to children, child services, as well as trying to catch criminals. There’s only so much that we can do.(Rachel)

The problem is, as I say, because we deal with the criminal side, if you take on too much responsibility over the emergency services side, we are going to be more paramedics from then on, rather than the police officer.(Thomas)

I would be pushing the other way to say that is not the role for the police at all. The police have a defined role and if you are going to cloud that role then you detract from other areas of society. The societal expectation is that police deal with crime and bad stuff.(Liam)

I think that our job should be to deal with criminality. I’m sick to death of mediating crap.(Ben)

People will go against the victim’s wishes, because if they don’t do that, the 9 o’clock jury will have a go at them, and if something happens, they’ll be responsible for it. So, you’re damned if you do, damned if you don’t. It’s almost like that blame culture.(Ian)

When I’m in work there’s very much a blame culture so it’s constantly that, there’s that train of thought that (pause) if this isn’t done properly, I’m right up the creek without a paddle. So, there’s that constant fear that if you don’t get it right then it gunna be you in front of the coroner or you in front of a disciplinary board.(Ben)

- I:

- It is all anonymous.

- R:

- ‘Police spokesman was heard to say...’ That is what the press do!

- I:

- I am not looking to catch you out, I am just interested in your…

- R:

- That is fine. You just get in this defensive mood whenever you are being asked an opinion. I have got to be really careful what I say because the media tend to take out all the context and just keep the punchline.

Until you physically come out and you do the job, you have experienced it, you take on the emotion of the people involved, you’re getting the emotional side, people crying, screaming, erratic ones who get to each other. That is something that you can’t train for in that sort of classroom environment.(Thomas)

I don’t like it. I don’t like it at all. I’d much rather go to a theft, or anything else, really. Domestics, they’re so tricky; they’re so difficult and they’re so familiar.(Jack)

It is very easy to say, ‘Why are you with that person? Why would you go back there?’ It is very easy to say that and from a logical perspective you would always say, ‘Why would you do that?’ but you can see why people do that because everyone has been in relationships where things aren’t great—not necessarily to that standard. Things aren’t great, but you persevere.(Liam)

I think it…(sigh)…it depends, from a…from a policing perspective I’ve done this job for a long time and I’ve become almost immune to is and I disassociate myself from my profession out of work.(Ben)

I mean, if you want horrific stories, then yes, I’ve got a catalogue of them in my brain that I sleep with every night(Emily)

You put it in your box, there’s always a box for it, and you put it away. And I couldn’t with that job, so I had a little bit of counselling. And that helped, I got through it, so I’m fine now from that.(Peter)

3.3. Global Theme 3: Head Injury Is Fearful

A bang on the back of the head is going to be more dangerous than a hit to the face, because that’s where your brain is, isn’t it?(Jack)

A bang to the head’s very serious; it will kill you. It might not even kill you there and then, it might kill you afterwards.(Jack)

We have got a pathological fear of head injuries as an organisation(Will)

The one thing that can make it a bit difficult is that the person who’s received the injury can sometimes be reluctant to talk about the mechanism of injury.(Michael)

It all comes down to what policing power we have and we don’t have the power to drag people to hospital and say, “You are going”.(Rachel)

I think you’ll find that with us in general, because of the nature of the head as such, and if anybody mentions headaches, ringing in their ears, feeling a bit fuzzy or whatever, we’d call somebody.(David)

You wouldn’t dream of leaving people with a head injury, just in case. We operate very much on that ‘just in case’, because if they did and they died, you are looking at job-losing territory.(Ian)

If it goes horribly wrong the whole world descends on you.(Will)

4. Discussion

Study Limitations and Directions for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Home Office. Information for Local Areas on the Change to the Definition of Domestic Violence and Abuse; Home Office: London, UK, 2013; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Office for National Statistics. Domestic Abuse in England and Wales: Year Ending March 2018. Statistical Bulletin 2018. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/bulletins/domesticabuseinenglandandwales/yearendingmarch2018 (accessed on 3 March 2020).

- Nolet, A.M.; Morselli, C.; Cousineau, M.-M. The social network of victims of domestic violence: A network-based intervention model to improve relational autonomy. Violence Against Women 2020, 27, 1630–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, D.; Trevillion, K.; Woodall, A.; Morgan, C.; Feder, G.; Howard, L. Barriers and facilitators of disclosures of domestic violence by mental health service users: Qualitative study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2011, 198, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monahan, K. Intimate partner violence (IPV) and neurological outcomes: A review for practitioners. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 2019, 28, 807–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higbee, M.; Eliason, J.; Weinberg, H.; Lifshitz, J.; Handmaker, H. Involving police departments in early awareness of concussion symptoms during domestic violence calls. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 2019, 28, 826–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellsberg, M.; Jansen, H.A.; Heise, L.; Watts, C.H.; Garcia-Moreno, C. Intimate partner violence and women’s physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence: An observational study. Lancet 2008, 371, 1165–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, G.; Agnew-Davies, R.; Bailey, J.; Howard, L.; Howarth, E.; Peters, T.J.; Sardinha, L.; Feder, G.S. Domestic violence and mental health: A cross-sectional survey of women seeking help from domestic violence support services. Glob. Health Action 2016, 9, 29890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Plichta, S.B. Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences: Policy and practice implications. J. Interpers. Violence 2004, 19, 1296–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, M.C. Intimate partner violence and adverse health consequences: Implications for clinicians. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2011, 5, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patch, M.; Anderson, J.C.; Campbell, J.C. Injuries of women surviving intimate partner strangulation and subsequent emergency health care seeking: An integrative evidence review. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2018, 44, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monahan, K.; Purushotham, A.; Biegon, A. Neurological implications of nonfatal strangulation and intimate partner violence. Future Neurol. 2019, 14, FNL21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buck, P.W. Mild traumatic brain injury: A silent epidemic in our practices. Health Soc. Work 2011, 36, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Othman, S.; Goddard, C.; Piterman, L. Victims’ barriers to discussing domestic violence in clinical consultations: A qualitative enquiry. J. Interpers. Violence 2014, 29, 1497–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overstreet, N.M.; Quinn, D.M. The intimate partner violence stigmatization model and barriers to help seeking. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 35, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kwako, L.E.; Glass, N.; Campbell, J.; Melvin, K.C.; Barr, T.; Gill, J.M. Traumatic brain injury in intimate partner violence: A critical review of outcomes and mechanisms. Trauma Violence Abus. 2011, 12, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banks, M.E. Overlooked but critical: Traumatic brain injury as a consequence of interpersonal violence. Trauma Violence Abus. 2007, 8, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jackson, H.; Philp, E.; Nuttall, R.L.; Diller, L. Traumatic brain injury: A hidden consequence for battered women. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2002, 33, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugate, M.; Landis, L.; Riordan, K.; Naureckas, S.; Engel, B. Barriers to domestic violence help seeking: Implications for intervention. Violence Against Women 2005, 11, 290–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, I.M. Victims’ perceptions of police response to domestic violence incidents. J. Crim. Justice 2007, 35, 498–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC). Everyone’s Business: Improving the Police Response to Domestic Abuse; Report; HMIC: London, UK, 2014.

- Richards, J. Police officer beliefs and attitudes towards intimate partner violence: A systematic review. Unpublished. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Exeter, Exeter, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, M. A Review of Domestic Abuse Training and Development Products and Services Provided by the College of Policing; Unpublished Report; College of Policing: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wire, J.; Myhill, A. Domestic Abuse Matters: Evaluation of First Responder Training; College of Policing: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, S. Institutionalizing police accountability reforms: The problem of making police reforms endure. St. Louis Univ. Public Law Rev. 2012, 32, 57–92. [Google Scholar]

- Batson, C.D.; Ahmad, N.Y. Using empathy to improve intergroup attitudes and relations. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 2009, 3, 141–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Chaiken, S. The advantages of an inclusive definition of attitude. Soc. Cogn. 2007, 25, 582–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, R.H. Attitudes as object-evaluation associations of varying strength. Soc. Cogn. 2007, 25, 603–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petty, R.E.; Brinol, P.; DeMarree, K.G. The Meta-Cognitive Model (MCM) of attitudes: Implications for attitude measurement, change, and strength. Soc. Cogn. 2007, 25, 657–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, J.; Wetherell, M. Discourse and Social Psychology; Sage: London, UK, 1987; ISBN 9780803980563. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H. Value orientations: Measurement, antecedents and consequences across nations. In Measuring Attitudes Cross-nationally: Lessons from the European Social Survey; Jowell, R., Roberts, C., Fitzgerald, R., Eva, G., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2007; pp. 169–204. ISBN 9781412919814. [Google Scholar]

- Dlamini, T.; Willmott, D.; Ryan, S. The basis and structure of attitudes: A critical evaluation of experimental, discursive, and social constructionist psychological perspectives. Psychol. Behav. Sci. Int. J. 2017, 6, 555680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siangchokyoo, N.; Sousa-Poza, A. Research methodologies: A look at the underlying philosophical foundations of research. Am. Soc. Eng. Manag. 2012, 2012, 714–722. [Google Scholar]

- Krosnick, J.A.; Judd, C.M.; Wittenbrink, B. Attitude measurement. In Handbook of Attitudes and Attitude Change; Mahwah, N.J., Ed.; Erlbaum: London, UK, 2015; pp. 21–76. ISBN 9781138010017. [Google Scholar]

- Gawronski, B.; De Houwer, J. Implicit measures in social and personality psychology. In Handbook of Research Methods in Social and Personality Psychology; Reis, H.T., Judd, C.M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 283–310. ISBN 9780511996481. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, J.; Hepburn, A. Discursive psychology: Mind and reality in practice. In Language, Discourse and Social Psychology; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2007; ISBN 9780230206168. [Google Scholar]

- Soukup, B. The measurement of “language attitudes”: A reappraisal from a constructionist perspective. In Language (de) Standardisation in Late Modern Europe: Experimental Studies; Grondelaers, S., Kristiansen, T., Eds.; Novus Press: Oslo, Norway, 2013; pp. 251–266. ISBN 9788270997411. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, J. Discursive social psychology: From attitudes to evaluative practices. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 9, 233–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gergen, K.J. On the very idea of social psychology. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2008, 71, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shotter, J.; Gergen, K.J. Social construction: Knowledge, self, others, and continuing the conversation. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 1994, 17, 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, P.L.; Berger, P.L.; Luckmann, T. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge; Anchor: Garden City, NY, USA, 1996; ISBN 978-0140135480. [Google Scholar]

- Gergen, K.J. Social constructionist inquiry: Context and implications. In The Social Construction of the Person; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1985; pp. 3–18. ISBN 978-1-4612-5076-0. [Google Scholar]

- Gergen, K.J. Social psychology as social construction: The emerging vision. In The Message of Social Psychology: Perspectives on Mind in Society; Blackwell Publishing: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1996; pp. 113–128. [Google Scholar]

- Howarth, C.; Foster, J.; Dorrer, N. Exploring the potential of the theory of social representations in community-based health research. J. Health Psychol. 2004, 9, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jackson, J.; Bradford, B.; Stanko, B.; Hohl, K. Just authority?: Trust in the police in England and Wales; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-0-631-19779-9. [Google Scholar]

- Crank, J.P. Understanding Police Culture, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 9781583605455. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius, N. From slavery and colonialism to Black Lives Matter: New mood music or more fundamental change? Equal. Divers. Incl. Int. J. 2020, 40, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quilter-Pinner, H.; Hochlaf, D. There is an alternative: Ending austerity in the UK; Institute for Public Policy Research, Centre for Economic Justice: London, UK, 2019; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- National Audit Office. Financial sustainability of police forces in England and Wales 2018; HC 1501 Session 2017–2019; National Audit Office: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, H. ‘Lean’ policing? New approaches to business process improvement across the UK police service. Public Money Manag. 2013, 33, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- College of Policing Leadership Review Coventry: College of Policing. 2015. Available online: http://www.college.police.uk/What-we-do/Development/Promotion/the-leadership (accessed on 26 May 2020).

- Caveney, N.; Scott, P.; Williams, S.; Howe-Walsh, L. Police reform, austerity and ‘cop culture’: Time to change the record? Polic. Soc. 2020, 30, 1210–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplowitz, M.D.; Hoehn, J.P. Do focus groups and individual interviews reveal the same information for natural resource valuation? Ecol. Econ. 2001, 36, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplowitz, M.D. Statistical analysis of sensitive topics in group and individual interviews. Qual. Quant. 2000, 34, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, F.; Coughlan, M.; Cronin, P. Interviewing in qualitative research: The one-to-one interview. Int. J. Ther. Rehabil. 2009, 16, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, F.E.; Watson, A.C. Police response to domestic violence: Situations involving veterans exhibiting signs of mental illness. Criminology 2015, 53, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fylan, F. Semi-structured interviewing. In A Handbook of Research Methods for Clinical and Health Psychology; Miles, J., Gilbert, P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005; ISBN 978-0198527565. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Starks, H.; Trinidad, S.B. Choose your method: A comparison of phenomenology, discourse analysis, and grounded theory. Qual. Health Res. 2017, 17, 1372–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Turunen, H.; Bondas, T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2013, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Jones, J.; Turunen, H.; Snelgrove, S. Theme development in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis. J. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 2016, 6, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heany, J. Social Regularities between Police Officers and Victims of Male Violence: Identifying the Limitations of Mandatory Arrest Policies. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, University of Missouri, Kansas City, MO, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Shearson, K. Policing intimate partner violence involving female victims: An exploratory study of the influence of relationship stage on the victim-police encounter. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, Victoria University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Reiner, R. Policing and the media. In Handbook of Policing; Newburn, T., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 9781843923237. [Google Scholar]

- Merry, S.; Power, N.; McManus, M.; Alison, L. Drivers of public trust and confidence in police in the UK. Int. J. Police Sci. Manag. 2012, 14, 118–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office for National Statistics Domestic Abuse and the Criminal Justice System, England and Wales: November 2019, Information on Responses to and Outcomes of Domestic Abuse Cases in the Criminal Justice System. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/articles/domesticabuseandthecriminaljusticesystemenglandandwales/november2019 (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Miers, D. Positivist victimology: A critique. Part 2: Critical victimology. Int. Rev. Vict. 1990, 1, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobl, R. Constructing the victim: Theoretical reflections and empirical examples. Int. Rev. Vict. 2004, 11, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.L. “Victims” and “survivors”: Emerging vocabularies of motive for battered women who stay. Sociol. Enq. 2005, 75, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greig-Midlane, J. A mixed-method exploration of neighbourhood policing reform in austerity era England and Wales. Ph.D. Thesis, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz, S.H.; Mitchell, D.; LaRussa-Trott, M.; Santiago, L.; Pearson, J.; Skiff, D.M.; Cerulli, C. An inside view of police officers’ experience with domestic violence. J. Fam. Violence 2011, 26, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waring, S. An examination of the impact of accountability and blame culture on police judgments and decisions in critical incident contexts. Unpublished. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Home Office Police Workforce, England and Wales, 31 March 2019, second edition. Statistical Bulletin, 2019, 11/19, 1–42. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/police-workforce-england-and-wales-31-march-2019 (accessed on 10 April 2020).

- Ard, K.L.; Makadon, H.J. Addressing intimate partner violence in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patients. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2011, 26, 930–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Richards, J.; Smithson, J.; Moberly, N.J.; Smith, A. “If It Goes Horribly Wrong the Whole World Descends on You”: The Influence of Fear, Vulnerability, and Powerlessness on Police Officers’ Response to Victims of Head Injury in Domestic Violence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7070. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18137070

Richards J, Smithson J, Moberly NJ, Smith A. “If It Goes Horribly Wrong the Whole World Descends on You”: The Influence of Fear, Vulnerability, and Powerlessness on Police Officers’ Response to Victims of Head Injury in Domestic Violence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(13):7070. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18137070

Chicago/Turabian StyleRichards, Jenny, Janet Smithson, Nicholas J. Moberly, and Alicia Smith. 2021. "“If It Goes Horribly Wrong the Whole World Descends on You”: The Influence of Fear, Vulnerability, and Powerlessness on Police Officers’ Response to Victims of Head Injury in Domestic Violence" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 13: 7070. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18137070

APA StyleRichards, J., Smithson, J., Moberly, N. J., & Smith, A. (2021). “If It Goes Horribly Wrong the Whole World Descends on You”: The Influence of Fear, Vulnerability, and Powerlessness on Police Officers’ Response to Victims of Head Injury in Domestic Violence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(13), 7070. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18137070