Sustainable Working Life in a Swedish Twin Cohort—A Definition Paper with Sample Overview

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

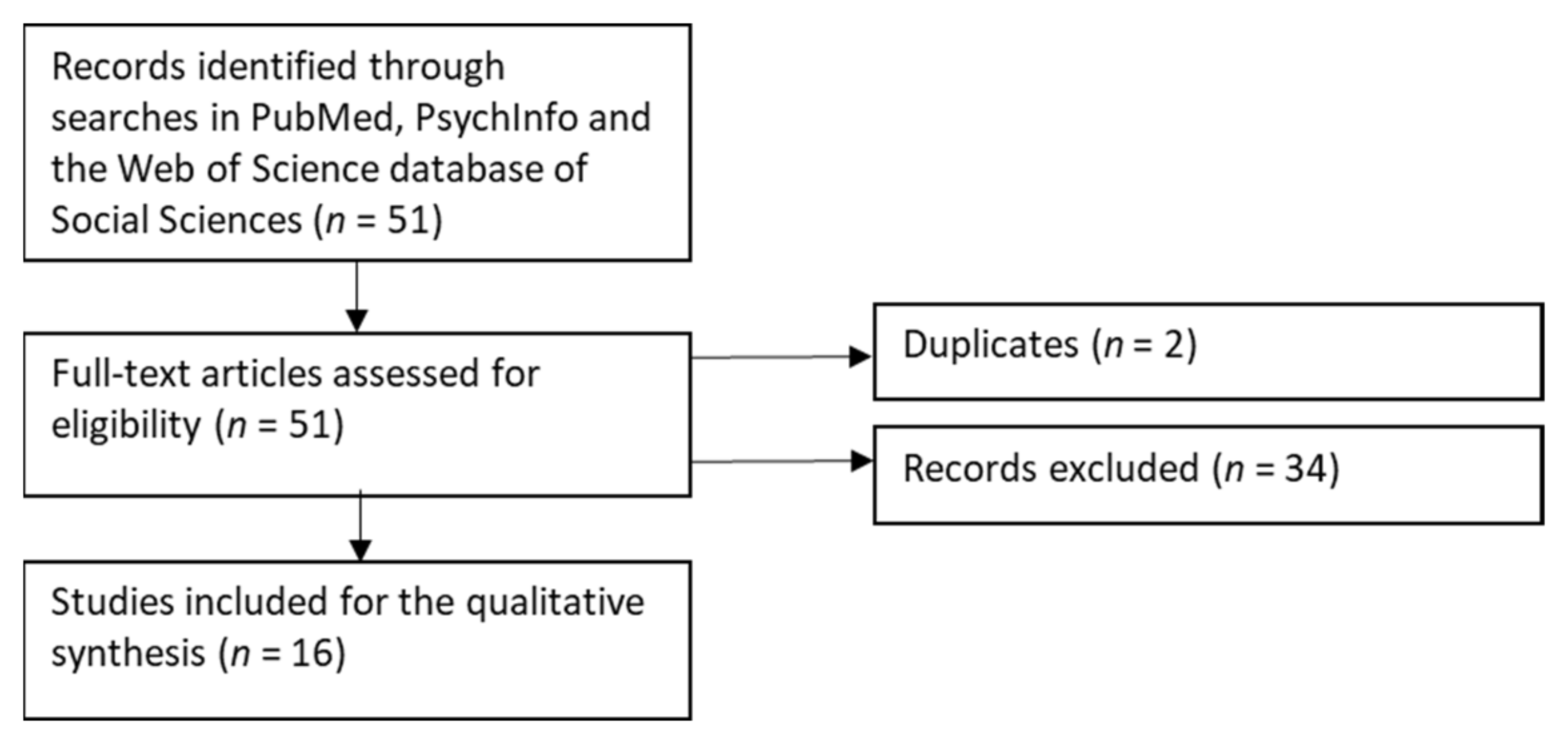

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. The Swedish Twin Project of Disability Pension and Sickness Absence

3. Results

3.1. Literature Review

- Health effects of the work environment (and associations with biological age)

- Function variation, diagnoses, and self-rated health

- Physical working environment: Load, vibration, wear, dangerous substances, climate, access to tools, etc.

- Mental work environment: Stress, demands, control, threats, violence, etc.

- Working time, working rate, recovery: schedule, shifts, breaks, etc.

- Finance (and associations with chronological age)

- Economy: Personal financial situation, security, employability, insurance, etc.

- Support and community (and associations with social age)

- Private social environment: Private life, family life, and leisure in relation to work

- Work social environment: Social support, discrimination, participation, attitudes, and leadership

- Execution of task (and associations with cognitive age)

- Work tasks, activity: Stimulation, motivation, and job satisfaction

- Competence, knowledgeability, employability, and development in relation to the task

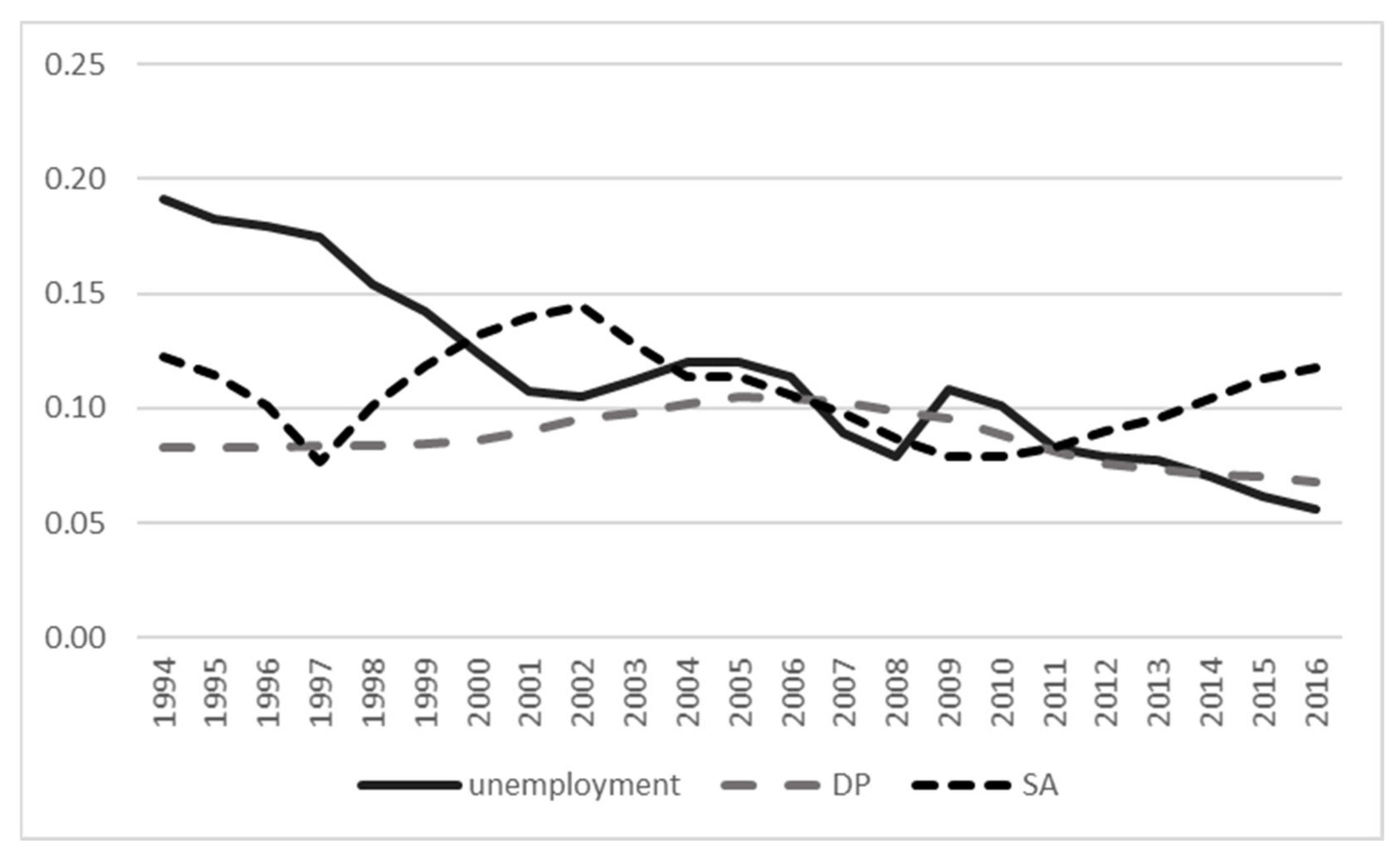

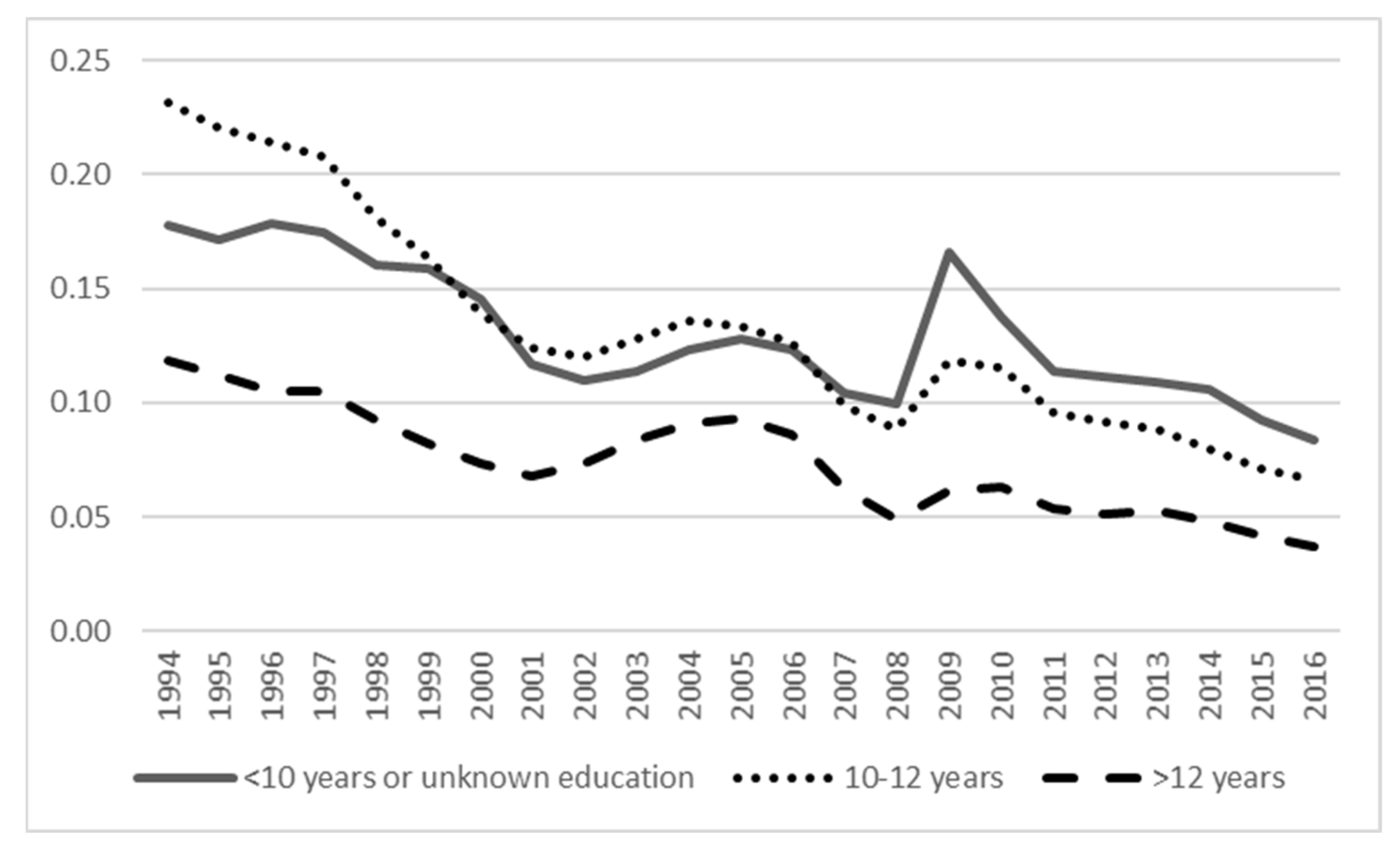

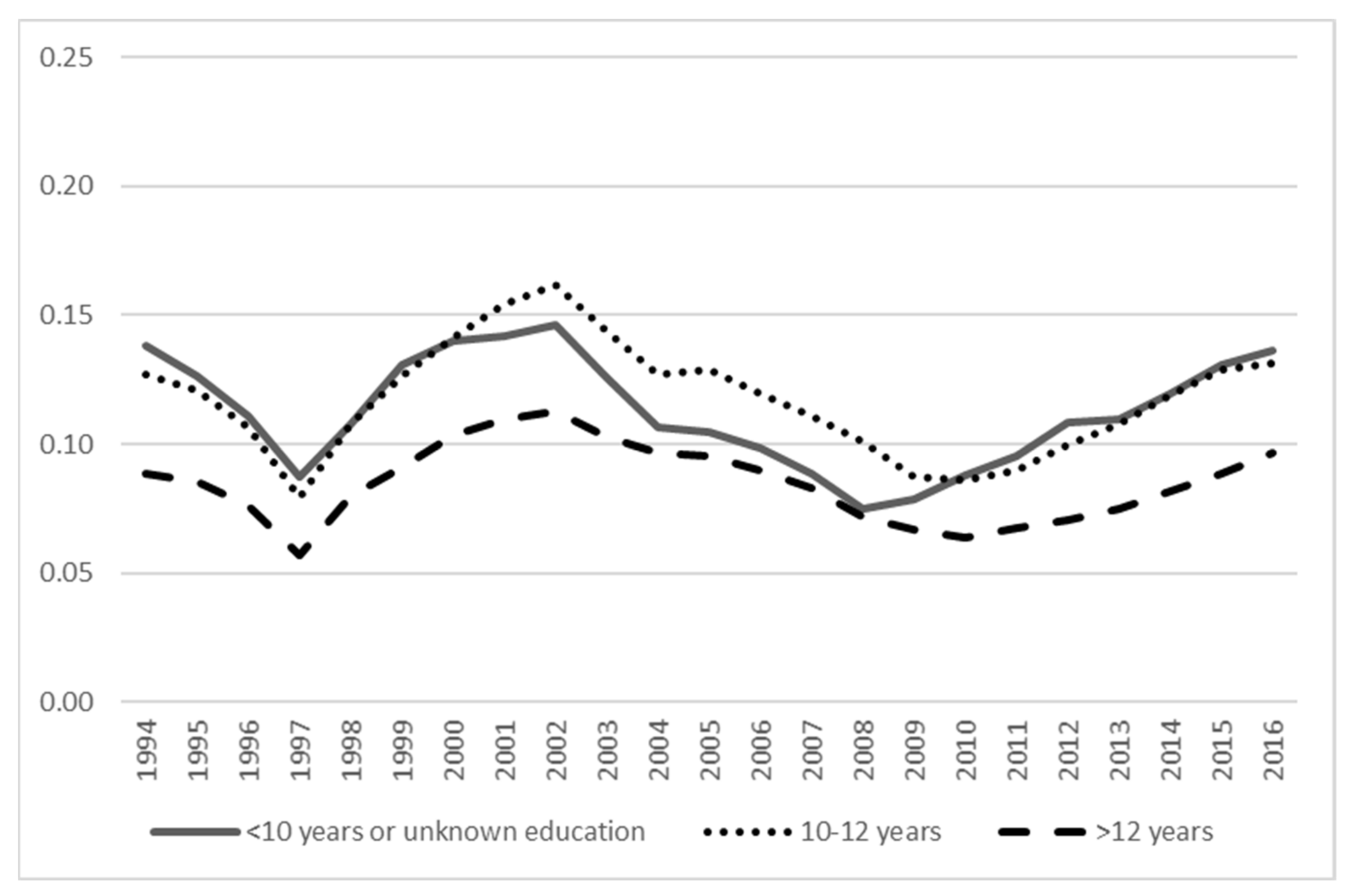

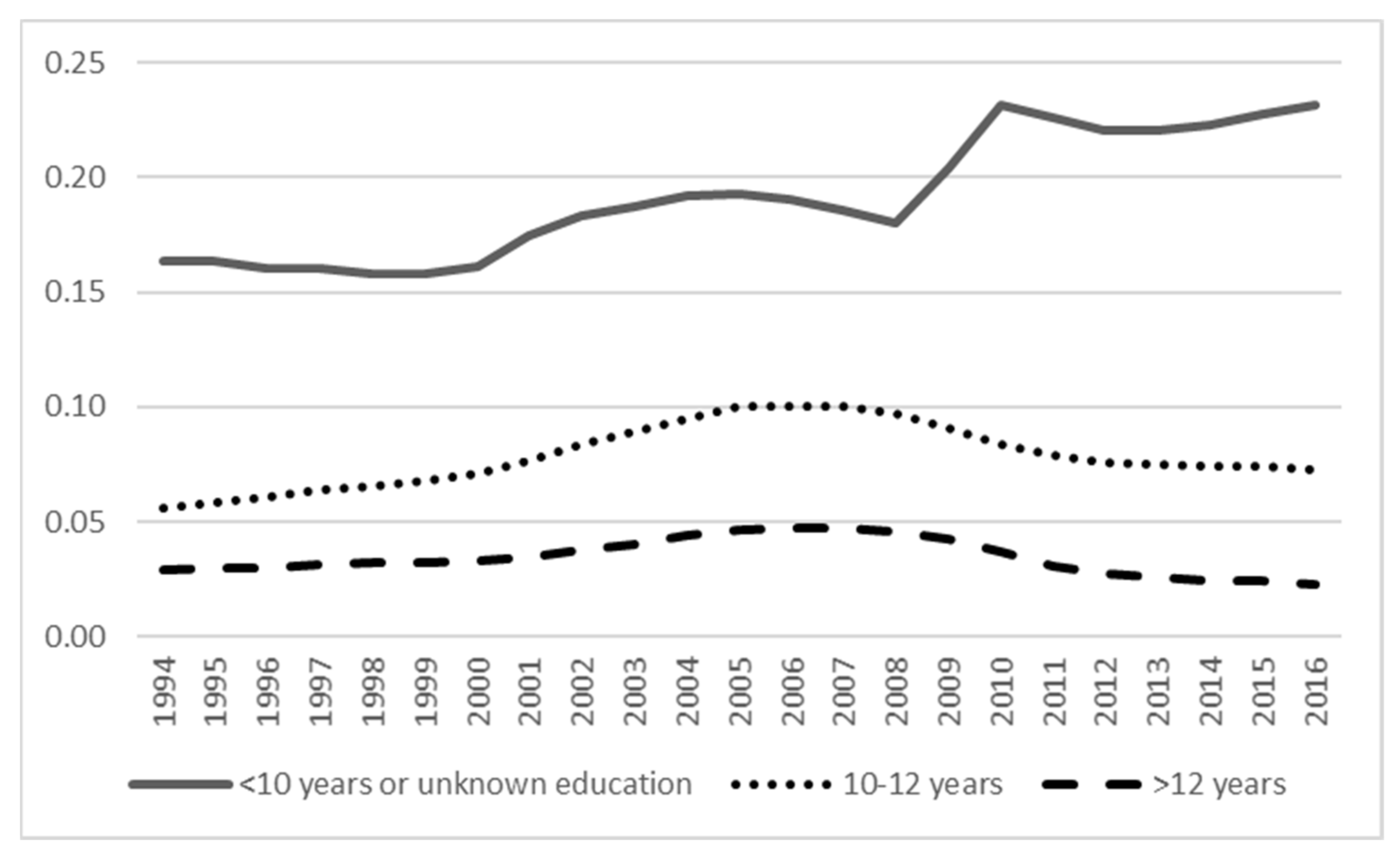

3.2. Prevalence of Sickness Absence, Disability Pension and Unemployment as Working Life Trajectories

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eurofound. Measuring Sustainable Work over the Life Course-Feasibility Study; European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (Eurofound): Dublin, Ireland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound. Sustainable Working over the Life Course: Concept Paper; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Thorsen, S.; Friborg, C.; Lundstrøm, B.; Kausto, J.; Örnelius, K.; Sundell, T.; Kalstø, Å.M.; Thune, O.; Gross, B.O.; Petersen, H.; et al. Sickness Absence in the Nordic Countries; Nordic Social Statistical Committee: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. Disability Inclusion Strategy and Action Plan 2014-17 a Twin-Track Approach of Mainstreaming and Disability-Specific Actions; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Sickness, Disability and Work: Breaking the Barriers; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Forouzanfar, M.H.; Afshin, A.; Alexander, L.T.; Anderson, H.R.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Biryukov, S.; Brauer, M.; Burnett, R.; Cercy, K.; Charlson, F.J.; et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016, 388, 1659–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. A Strategy for Smart, Sustainable and Inclusive Growth 2010; Communication from the Commission, Europe 2020; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kivimäki, M.; Head, J.; Ferrie, J.E.; Shipley, M.J.; Vahtera, J.; Marmot, M.G. Sickness absence as a global measure of health: Evidence from mortality in the Whitehall II prospective cohort study. BMJ 2003, 327, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plomin, R.; Colledge, E. Genetics and Psychology: Beyond Heritability. Eur. Psychol. 2001, 6, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narusyte, J.; Ropponen, A.; Alexanderson, K.; Svedberg, P. Internalizing and externalizing problems in childhood and adolescence as predictors of work incapacity in young adulthood. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narusyte, J.; Ropponen, A.; Alexanderson, K.; Svedberg, P. Genetic and Environmental Influences on Disability Pension Due To Mental Diagnoses: Limited Importance of Major Depression, Generalized Anxiety, and Chronic Fatigue. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 2016, 19, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ropponen, A.; Svedberg, P. Single and additive effects of health behaviours on the risk for disability pensions among Swedish twins. Eur. J. Public Health 2014, 24, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svedberg, P.; Ropponen, A.; Alexanderson, K.; Lichtenstein, P.; Narusyte, J. Genetic susceptibility to sickness absence is similar among women and men: Findings from a Swedish twin cohort. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 2012, 15, 642–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, R.; Svedberg, P.; Narusyte, J. Associations between adolescent social phobia, sickness absence and unemployment: A prospective study of twins in Sweden. Eur. J. Public Health 2019, 29, 931–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böckerman, P.; Maczulskij, T. Unfit for work: Health and labour-market prospects. Scand. J. Public Health 2018, 46, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narusyte, J.; Ropponen, A.; Silventoinen, K.; Alexanderson, K.; Kaprio, J.; Samuelsson, Å.; Svedberg, P. Genetic Liability to Disability Pension in Women and Men: A Prospective Population-Based Twin Study. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narusyte, J.; Ropponen, A.; Silventoinen, K.; Alexanderson, K.; Kaprio, J.; Samuelsson, Å.; Svedberg, P. The Genetic Liability to Disability Retirement: A 30-Year Follow-Up Study of 24,000 Finnish Twins. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjerde, L.C.; Knudsen, G.P.; Czajkowski, N.; Gillespie, N.; Aggen, S.H.; Røysamb, E.; Reichborn-Kjennerud, T.; Tambs, K.; Kendler, K.S.; Orstavik, R.E. Genetic and environmental contributions to long-term sick leave and disability pension: A population-based study of young adult Norwegian twins. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 2013, 16, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Watson, M. Guidance on Conducting a Systematic Literature Review. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2019, 39, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLOS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasek, R.A.; Theorell, T. Healthy Work: Stress, Productivity and the Reconstruction of Working Life; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein, P.; De Faire, U.; Floderus, B.; Svartengren, M.; Svedberg, P.; Pedersen, N.L. The Swedish Twin Registry: A unique resource for clinical, epidemiological and genetic studies. J. Intern. Med. 2002, 252, 184–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svedberg, P.; Ropponen, A.; Lichtenstein, P.; Alexanderson, K. Are self-report of disability pension and long-term sickness absence accurate? Comparisons of self-reported interview data with national register data in a Swedish twin cohort. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludvigsson, J.F.; Svedberg, P.; Olén, O.; Bruze, G.; Neovius, M. The longitudinal integrated database for health insurance and labour market studies (LISA) and its use in medical research. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 34, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneklin, C.; Gorli, M. “Sustainability at Work” through an Action-Research Perspective: Knowledge Creation and Validity Concerns. TPM 2007, 14, 185–206. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, V.; Pit, S.W.; Honeyman, P.; Barclay, L. Prolonging a sustainable working life among older rural GPs: Solutions from the horse’s mouth. Rural Remote Health 2013, 13, 2369. [Google Scholar]

- Koolhaas, W.; van der Klink, J.J.; Vervoort, J.P.; de Boer, M.R.; Brouwer, S.; Groothoff, J.W. In-depth study of the workers’ perspectives to enhance sustainable working life: Comparison between workers with and without a chronic health condition. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2013, 23, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leider, P.C.; Boschman, J.S.; Frings-Dresen, M.H.; van der Molen, H.F. Effects of job rotation on musculoskeletal complaints and related work exposures: A systematic literature review. Ergonomics 2015, 58, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vänje, A. Sick Leave—A Signal of Unequal Work Organizations? Gender perspectives on work environment and work organizations in the health care sector: A knowledge review. Nord. J. Work. Life Stud. 2015, 5, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, K. Conceptualisation of ageing in relation to factors of importance for extending working life—A review. Scand. J. Public Health 2016, 44, 490–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, A.; Orvik, A.; Strandmark, M.; Nordsteien, A.; Torp, S. Management and Leadership Approaches to Health Promotion and Sustainable Workplaces: A Scoping Review. Societies 2017, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forslin, M.; Fink, K.; Hammar, U.; von Koch, L.; Johansson, S. Predictors for Employment Status in People With Multiple Sclerosis: A 10-Year Longitudinal Observational Study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2018, 99, 1483–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wålinder, R.; Runeson-Broberg, R.; Arakelian, E.; Nordqvist, T.; Runeson, A.; Rask-Andersen, A. A supportive climate and low strain promote well-being and sustainable working life in the operation theatre. Ups. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 123, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GGyllensten, K.; Wentz, K.; Håkansson, C.; Hagberg, M.; Nilsson, K. Older assistant nurses’ motivation for a full or extended working life. Ageing Soc. 2019, 39, 2699–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L.; Ford, H.; Stroud, A.; Madill, A. Tortoise or hare? Supporting the chronotope preference of employees with fluctuating chronic illness symptoms. Psychol. Health 2019, 34, 695–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blomé, M.W.; Borell, J.; Håkansson, C.; Nilsson, K. Attitudes toward elderly workers and perceptions of integrated age management practices. Int J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2020, 26, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyllensten, K.; Torén, K.; Hagberg, M.; Söderberg, M. A sustainable working life in the car manufacturing industry: The role of psychosocial factors, gender and occupation. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindmark, U.; Ahlstrand, I.; Ekman, A.; Berg, L.; Hedén, L.; Källstrand, J.; Larsson, M.; Nunstedt, H.; Oxelmark, L.; Pennbrant, S.; et al. Health-promoting factors in higher education for a sustainable working life-protocol for a multicenter longitudinal study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, K. A sustainable working life for all ages—The swAge-model. Appl. Ergon. 2020, 86, 103082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunstedt, H.; Eriksson, M.; Obeid, A.; Hillström, L.; Truong, A.; Pennbrant, S. Salutary factors and hospital work environments: A qualitative descriptive study of nurses in Sweden. BMC Nurs. 2020, 19, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Ropponen, A.; Narusyte, J.; Helgadóttir, B.; Bergström, G.; Blom, V.; Svedberg, P. Adverse outcomes of chronic widespread pain and common mental disorders in individuals with sickness absence—A prospective study of Swedish twins. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ropponen, A.; Narusyte, J.; Silventoinen, K.; Svedberg, P. Health behaviours and psychosocial working conditions as predictors of disability pension due to different diagnoses: A population-based study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgadóttir, B.; Mather, L.; Narusyte, J.; Ropponen, A.; Blom, V.; Svedberg, P. Transitioning from sickness absence to disability pension—The impact of poor health behaviours: A prospective Swedish twin cohort study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e031889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mather, L.; Ropponen, A.; Mittendorfer-Rutz, E.; Narusyte, J.; Svedberg, P. Health, work and demographic factors associated with a lower risk of work disability and unemployment in employees with lower back, neck and shoulder pain. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2019, 20, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Björkenstam, E.; Narusyte, J.; Alexanderson, K.; Ropponen, A.; Kjeldgård, L.; Svedberg, P. Associations between childbirth, hospitalization and disability pension: A cohort study of female twins. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e101566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Author(s) (Ref) | Definition | Comparative Features | Number of Citation | Time-Span of Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | Kaneklin and Gorli [25] | Sustainable working life is the capacity for organizations to create and regenerate value through the application of participative policies and practices to promote both organizational performances and people’s well-being. Relief of social dimension that inhabits organizational changes and maintain it close to the functional and strategic organizational changes, since the structural and functional dimensions of an organization must come together with the social and cultural dimensions for a sustainable working life. | Population: Healthcare sector organizations in Italy. Design: Action research. | 2 | 2007–2020 |

| 2013 | Hansen et al. [26] | Personal- and practice-based, professional, and systemic themes containing a number of sub-themes representing the experiences (i.e., ability to work part-time, achieve a healthy work-life balance, etc.), initiatives (e.g., alternatives to ownership of practice or develop teams with multidisciplinary support), or conditions (e.g., payment systems supportive of continued involvement in teaching or educational opportunities) that promote a long and sustainable working life in rural general practice. | Population: Australian rural general practitioners >45 years on age. Design: Semi-structured qualitative interview. | 0 | - |

| 2013 | Koolhaas et al. [27] | The increase in problems due to ageing and health-related problems from the age of 45 years onwards implies the importance of attention to obstacles and retention factors for maintaining or enhancing a sustainable working life. | Population: Workers aged ≥45 years in nine different companies in Netherlands. Design: A cross-sectional in-depth survey. | 13 | 2013–2020 |

| 2015 | Leider et al. [28] | Sustainable working life consists of parameters: work ability, productivity, vitality, and/or work role functioning. | Population: - Design: Systematic literature review utilizing Web of Science, Medline/PubMed and Embase to identify papers published in peer-reviewed journals between 1997 and 2013. | 42 | 2015–2020 |

| 2015 | Vänje [29] | Sustainable working life includes the perspectives of crafting employees’ individual resources as well as collaboration between employees and their managers in order to create organizational development. | Population: - Design: Literature review using the Royal Institute of Technology’s (KTH’s) library search engine KTHB Primo, EndNote and the Social Sciences Citation Index at Web of Science (ISI), the Swedish search engines LIBRIS (http://libris.kb.se/) and KVINNSAM (http://www.ub.gu.se/kvinn/kvinnsam/) from the mid-1980s until 2014. | 5 | 2015–2019 |

| 2016 | Nilsson [30] | Four different concepts of ageing; the nine factors of importance for working life; and their relation to older workers’ decision to extend their working life or retire. Employees’ biological ageing is important due to individual health and well-being in association with their work situation (work pace, time, and environment); employees’ chronological ageing involves statutory retirement age, social insurance, policies and economic incentives in working life and society. Adequate personal finances, i.e., providing for a living, food, and essential factors, but also motivation factors (e.g., the possibility for social inclusion/participation in an inspiring work situation and for motivating and stimulating activities and tasks based on the individuals’ knowledge) are important. | Population: - Design: Literature review in Medline, PubMed, Scopus, Science Direct, Web of Knowledge, Cochrane Library and Google Scholar, in addition Swedish library database LIBrIS and Lund University library database, and also the Organisation for economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the World Health Organisation (WHO), the World economic Forum (WeF), and the European Union (EU) in 2003–2015. | 7 | 2016–2020 |

| 2017 | Eriksson et al. [31] | Sustainable workplaces as work environments that embrace factors that contribute to employee health and well-being, as well as organizational efficiency. By integrating human and economic values, sustainable workplaces can even impact societal effectiveness. | Population: - Design: Scoping review in Web of Science, Scopus, Pubmed, Cinahl, Academic Search Premier, PsycInfo, and Embase for 2009–2014. | 3 | 2019–2020 |

| 2018 | Forslin et al. [32] | A well-functioning balance between a working and private life is important for a sustainable working life over time. | Population: Those with a definite MS diagnosis and an outpatient appointment with a neurologist in Sweden and alive, of working age at the 10-year follow-up (<55 years of age at baseline). Design: A 10-year longitudinal observational study. | 5 | 2019–2020 |

| 2018 | Wålinder et al. [33] | Social support and low strain (JCD-model) are linked with workers’ well-being and a sustainable working life in the health-care sector. | Population: Hospital workers in university hospitals in Sweden Design: Cross-sectional survey study | 0 | - |

| 2019 | Gyllensten et al. [34] | Sustainable working life according to swAge-model depends on health, physical work environment, mental/psycho-social work environment, working time and work pace, knowledge and competence, work motivation and work satisfaction, the attitude of managers and the organisation/enterprise towards older workers, the family situation, and leisure activities. | Population: Employees of health and elderly care homes in Sweden Design: Focus group interviews | 1 | 2019 |

| 2019 | Thompson et al. [35] | The concept of sustainable working life includes organizations devising career paths that support staff to retain their health (physical and mental), productivity, and motivation over an extended period of employment. Vulnerable employees may cycle between the more- and the less-adaptive poles of each chronotope, and even between chrontopes, given that people with chronic illness are known to draw on a range of self-management strategies over time. | Population: Multiplesclerosis patients in UK. Design: Dialogical analysis of focus group interviews. | 0 | - |

| 2020 | Blomé et al. [36] | The swAge-model: the individual motives and considerations for continuing to work and the older workers’ retirement decisions are based on: (a) their health in relation to the work situation and work environment versus health in retirement; (b) their personal economic situation in employment versus in retirement; (c) their opportunities for social inclusion in working life situations versus in retirement; (d) their opportunities for meaningful and self-crediting activities in working life versus in retirement | Population: Focus group interviews of 3–7 older workers, managers, trade union representatives, and human resource personnel from public organizations, large private companies and from private small-to-medium-sized enterprises in Sweden. Design: Secondary analysis of age management with the theoretical swAge- model. | 3 | 2020 |

| 2020 | Gyllensten et al. [37] | Continuing to work at an older age is determined by “push factors,” i.e., chronic diseases, physical demands, and poor working conditions, and “‘pull factors,” such as one’s spouse not working, care-taking of relatives, and leisure time expectations. Additionally, norms about working and retiring, economic incentives, attitudes at the workplace, work satisfaction, and social relationships at work and home are important factors for extended working life. | Population: All individuals employed at one car manufacturer in Sweden during 2005–2015. Design: A case-control study for 10-year follow-up. | 0 | - |

| 2020 | Lindmark et al. [38] | Focus on the prevention of ill health, health-promoting factors (e.g., occupational balance, emotional intelligence, social interaction/teamwork) for improvement of people’s capacity to develop abilities and resources to feel good and cope with different situations in a healthy way are essential for health and sustainable working life. | Population: Students of higher education programs in the healthcare and social work sectors in Sweden. Design: Baseline results of a multicentre longitudinal study. | 0 | - |

| 2020 | Nilsson [39] | The swAge-model describes three influence levels of importance for work-life participation and to a sustainable, extended working life: the individual level, micro level; the organizational and enterprise level, meso level; and the society level, macro level. | Population: - Design: Descriptive for swAge-model which will be developed based on grounded theory using qualitative and quantitative studies, intervention projects, and literature reviews. | 1 | 2020 |

| 2020 | Nunstedt [40] | A reduced workload, varied tasks, individual schedules, clear leadership, and cooperation between nurses and other professionals are factors that contribute to a good working climate, sense of coherence, and meaningfulness. Hence, these can be used for action programmes, which, in turn, can promote a sustainable working life. | Population: Nurses in a hospital in western Sweden. Design: Qualitative and descriptive in design including a literature review, interviews, a qualitative content analysis, and a deductive approach for theoretical discussion. | 1 | 2021 |

| Author(s) (Ref) | Measure | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Kaneklin and Gorli [25] | n.a. | n = 14 middle managers |

| Hansen, Pit, Honeyman, and Barclay [26] |

| n = 16 |

| Koolhaas, van der Klink, Vervoort, de Boer, Brouwer, and Groothoff [27] | Workers’ perspectives on problems, obstacles, retention factors, and needs due to ageing classified with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). | n = 3008 workers, response rate 36% |

| Leider, Boschman, Frings-Dresen, and van der Molen [28] |

| Search terms: job rotation, musculoskeletal complaints, terms for related exposures and terms for sustainable working life parameters. n = 16 included studies. |

| Vänje [29] | n.a. | |

| Nilsson [30] | Health; economic incentives; family, leisure, and surrounding society; physical work environment; mental work environment; work pace and working hours; competence and skills; motivation and work satisfaction; and the attitude of managers and organisation to older workers. | Discourse analysis of documents was used in an integrative review including 128 articles. |

| Eriksson, Orvik, Strandmark, Nordsteien, and Torp [31] | n.a. | In-depth analysis of 20 studies |

| Forslin, Fink, Hammar, von Koch, and Johansson [32] | Employment status at the 10-year follow-up categorised as full-time work, part-time work (working, but less than full time), and no work. | Baseline and follow-up surveys, n = 154 |

| Wålinder, Runeson-Broberg, Arakelian, Nordqvist, Runeson, and Rask-Andersen [33] | Well-being at work Zest for work (i.e., emotions about work) Intention to stop working with health care | n = 1405 hospital employees |

| Gyllensten, Wentz, Håkansson, Hagberg, and Nilsson [34] | Organisational issues

| n = six focus groups with four to eight participants in each group |

| Thompson, Ford, Stroud, and Madill [35] | n.a. | Dialogical analysis of 20 workers |

| Blomé, Borell, Håkansson, and Nilsson [36] |

| Qualitative interviews, n = 16 |

| Gyllensten, Torén, Hagberg, and Söderberg [37] | Employers’ register for employment status: active at work, retired (either retired at the age 55–62 or working ≥63 years during the observation years) | n = 572 cases and 771 controls |

| Lindmark, Ahlstrand, Ekman, Berg, Hedén, Källstrand, Larsson, Nunstedt, Oxelmark, Pennbrant, Sundler, and Larsson [38] | Health-promoting dimensions:

| n = 2283 students |

| Nilsson [39] |

| Grounded theory |

| Nunstedt [40] |

| n = 12 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ropponen, A.; Wang, M.; Narusyte, J.; Silventoinen, K.; Böckerman, P.; Svedberg, P. Sustainable Working Life in a Swedish Twin Cohort—A Definition Paper with Sample Overview. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5817. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115817

Ropponen A, Wang M, Narusyte J, Silventoinen K, Böckerman P, Svedberg P. Sustainable Working Life in a Swedish Twin Cohort—A Definition Paper with Sample Overview. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(11):5817. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115817

Chicago/Turabian StyleRopponen, Annina, Mo Wang, Jurgita Narusyte, Karri Silventoinen, Petri Böckerman, and Pia Svedberg. 2021. "Sustainable Working Life in a Swedish Twin Cohort—A Definition Paper with Sample Overview" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 11: 5817. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115817

APA StyleRopponen, A., Wang, M., Narusyte, J., Silventoinen, K., Böckerman, P., & Svedberg, P. (2021). Sustainable Working Life in a Swedish Twin Cohort—A Definition Paper with Sample Overview. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(11), 5817. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115817