Dissociation, Cognitive Reflection and Health Literacy Have a Modest Effect on Belief in Conspiracy Theories about COVID-19

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Participants

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Predictors of Conspiracy Beliefs (H1–H4)

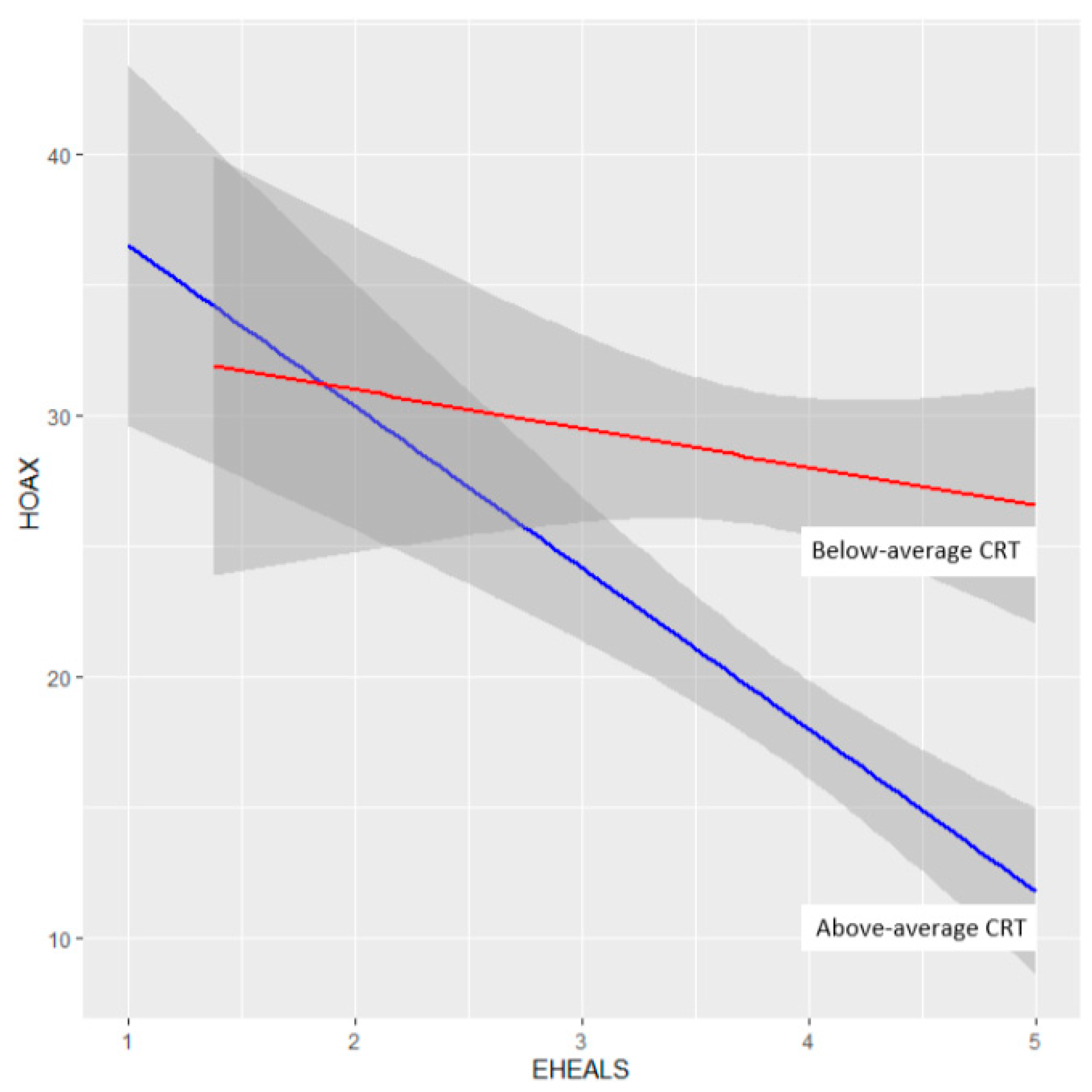

3.3. Moderation of the Link between eHEALS and Conspiracy Beliefs (H5–H6)

4. Discussion

4.1. Limits

4.2. Future Research

4.3. Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Novel Coronavirus. Situation Report—13. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200202-sitrep-13-ncov-v3.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2021).

- Hartman, T.K.; Marshall, M.; Stocks, T.V.; McKay, R.; Bennett, K.M.; Butter, S.; Miller, J.G.; Hyland, P.; Levita, L.; Bentall, R.P.; et al. Different Conspiracy Theories Have Different Psychological and Social Determinants: Comparison of Three Theories about the Origins of the COVID-19 Virus in a Representative Sample. PsyArXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, J.; Marchlewska, M.; Molenda, Z.; Górska, P.; Gawęda, Ł. Adherence to safety and self-isolation guidelines, conspiracy and paranoia-like beliefs during COVID-19 pandemic in Poland—Associations and moderators. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 294, 113540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, D.; Jamieson, K.H. Conspiracy theories as barriers to controlling the spread of COVID-19 in the U.S. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 263, 113356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhoff, R.; Lamberty, P. A Bioweapon or a Hoax? The Link between Distinct Conspiracy Beliefs about the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Outbreak and Pandemic Behavior. Soc. Psychol. Person. Sci. 2020, 11, 1110–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, F.; Clarke, S.; Stopa, L.; Bell, L.; Rouse, H.; Ainsworth, C.; Fearon, P.; Waller, G. Towards a cognitive model and measure of dissociation. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2004, 35, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoica, C.A.; Umbreș, R. Suspicious minds in times of crisis: Determinants of Romanians’ beliefs in COVID-19 conspiracy theories. Eur. Soc. 2020, 23 (Suppl. 1), S246–S261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghiyeh, H.; Khanahmadi, I.; Farhadbeigi, P.; Karimi, N. Cognitive Reflection and the Coronavirus Conspiracy Beliefs. PsyArXiv 2020, preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, G.; Cheyne, J.A.; Barr, N.; Koehler, D.J.; Fugelsang, J.A. On the Reception and Detection of Pseudo-profound Bullshit. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2015, 10, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stagnaro, M.N.; Ross, R.M.; Pennycook, G.; Rand, D.G. Cross-cultural support for a link between analytic thinking and disbelief in God: Evidence from India and the United Kingdom. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2019, 14, 179–186. [Google Scholar]

- Okan, O.; Bollweg, T.M.; Berens, E.-M.; Hurrelmann, K.; Bauer, U.; Schaeffer, D. Coronavirus-Related Health Literacy: A Cross-Sectional Study in Adults during the COVID-19 Infodemic in Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickles, K.; Cvejic, E.; Nickel, B.; Copp, T.; Bonner, C.; Leask, J.; Ayre, J.; Batcup, C.; Cornell, S.; McCaffery, K.J.; et al. COVID-19 misinformation trends in Australia: Prospective longitudinal national survey. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e23805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.; Paasche-Orlow, M.K.; McCormack, L.A. The state of the science of health literacy measurement. Inf. Serv. Use 2017, 37, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vitriol, J.A.; Marsh, J.K. The illusion of explanatory depth and endorsement of conspiracy beliefs. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 48, 955–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, K. Do people overestimate their information literacy skills? A systematic review of empirical evidence on the dunning-kruger effect. Commun. Inf. Lit. 2016, 10, 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duplaga, M. The Determinants of Conspiracy Beliefs Related to the COVID-19 Pandemic in a Nationally Representative Sample of Internet Users. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duplaga, M.; Grysztar, M. The Association between Future Anxiety, Health Literacy and the Perception of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2021, 9, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aharon, A.A.; Nehama, H.; Rishpon, S.; Baron-Epel, O. Parents with high levels of communicative and critical health literacy are less likely to vaccinate their children. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 768–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Health Literacy: The Solid Facts; Kickbusch, I., Pelikan, J.M., Apfel, F., Tsouros, A.D., Eds.; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/128703/e96854.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Ptáček, R.; Bob, P. Metody diagnostiky disociativních symptomů. Czech Slovak Psychiatry 2009, 105, 163–172. [Google Scholar]

- Bruder, M.; Haffke, P.; Neave, N.; Nouripanah, N.; Imhoff, R. Measuring Individual Differences in Generic Beliefs in Conspiracy Theories Across Cultures: Conspiracy Mentality Questionnaire. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Frederick, S. Cognitive reflection and decision making. J. Econ. Perspect. 2005, 19, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Norman, C.D.; Skinner, H.A. eHEALS: The eHealth literacy scale. J. Med. Internet Res. 2006, 8, e507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wu, A.D.; Zumbo, B.D. Understanding and using mediators and moderators. Soc. Indic. Res. 2008, 87, 367–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revelle, W. How to Use the Psych Package for Mediation/Moderation/Regression Analysis. 2021. Available online: http://personality-project.org/r/psych/HowTo/mediation.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2020. Available online: https://www.r-project.org (accessed on 20 December 2020).

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan LD, A.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Yutani, H.; et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revelle, W. psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research. R Package. 2020. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=psych (accessed on 27 February 2021).

- Fletcher, T.D. QuantPsyc: Quantitative Psychology Tools. R Package. 2012. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=QuantPsyc (accessed on 27 February 2021).

- Charlton, E. Conspiracy Theories and Dissociative experiences: The Role of Personality and Paranormal Beliefs. Undergraduate Thesis, Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dyrendal, A.; Kennair, L.; Bendixen, M. Predictors of belief in conspiracy theory: The role of individual differences in schizotypal traits, paranormal beliefs, social dominance orientation, right wing authoritarianism and conspiracy mentality. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2021, 173, 110645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwin, H.; Neave, N.; Holmes, J. Belief in conspiracy theories. The role of paranormal belief, paranoid ideation and schizotypy. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2011, 50, 1289–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattet, S.L.; Bursik, K. Investigating the personality correlates of paranormal belief and precognitive experience. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2001, 31, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, K.M.; Sutton, R.M.; Callan, M.J.; Dawtry, R.J.; Harvey, A.J. Someone is pulling the strings: Hypersensitive agency detection and belief in conspiracy theories. Think. Reason. 2016, 22, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mosleh, M.; Pennycook, G.; Arechar, A.A.; Rand, D.G. Cognitive reflection correlates with behavior on Twitter. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, G.; Rand, D.G. Who falls for fake news? The roles of bullshit receptivity, overclaiming, familiarity, and analytic thinking. J. Pers. 2020, 88, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, K.M.; Uscinski, J.E.; Sutton, R.M.; Cichocka, A.; Nefes, T.; Ang, C.S.; Deravi, F. Understanding Conspiracy Theories. Polit. Psychol. 2019, 40 (Suppl. 1), 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hart, W.; Albarracín, D.; Eagly, A.H.; Brechan, I.; Lindberg, M.J.; Merrill, L. Feeling validated versus being correct: A meta-analysis of selective exposure to information. Psychol Bull. 2009, 135, 555–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Park, C.L. Making Sense of the Meaning Literature: An Integrative Review of Meaning Making and Its Effects on Adjustment to Stressful Life Events. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 136, 257–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunda, Z. The case for motivated reasoning. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 108, 480–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oleksy, T.; Wnuk, A.; Maison, D.; Łyś, A. Content matters. Different predictors and social consequences of general and government-related conspiracy theories on COVID-19. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2021, 168, 110289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternisko, A.; Cichocka, A.; Cislak, A.; van Bavel, J.J. Collective Narcissism Predicts the Belief and Dissemination of Conspiracy Theories during the COVID-19 Pandemic. PsyArXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, S. Searching for General Model of Conspiracy Theories and Its Implication for Public Health Policy: Analysis of the Impacts of Political, Psychological, Structural Factors on Conspiracy Beliefs about the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 18, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n | Min | Max | Mean | Med | Standard Deviation | Standard Error | Skew | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DES | 866 | 0 | 78.21 | 17.58 | 14.11 | 13.1 | 0.45 | 1.24 | 1.53 |

| CM | 866 | 2 | 100 | 56.04 | 58 | 20.21 | 0.69 | −0.15 | −0.47 |

| HOAX | 866 | 0 | 100 | 23.60 | 16.67 | 24.22 | 0.82 | 0.95 | 0 |

| CREATED | 866 | 0 | 100 | 29.77 | 26.67 | 21.76 | 0.74 | 0.66 | −0.11 |

| eHEALS | 866 | 1 | 5 | 3.85 | 4 | 0.82 | 0.03 | −0.66 | 0.07 |

| CRT | 842 | 0 | 3 | 1.51 | 2 | 1.19 | 0.04 | −0.05 | −1.52 |

| BSR | 866 | 1 | 5 | 2.53 | 2.6 | 0.76 | 0.03 | 0.17 | −0.26 |

| No. of Items | Cronbach Alpha | DES | CM | HOAX | CREATED | eHEALS | CRT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DES | 28 | 0.93 | – | |||||

| CM | 5 | 0.82 | 0.33 | – | ||||

| HOAX | 3 | 0.88 | 0.15 | 0.30 | – | |||

| CREATED | 3 | 0.67 | 0.17 | 0.42 | 0.46 | – | ||

| eHEALS | 8 | 0.92 | −0.08 | −0.06 | −0.14 | −0.11 | – | |

| CRT | 3 | 0.73 | −0.16 | −0.19 | −0.21 | −0.25 | 0.05 | – |

| BSR | 5 | 0.63 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.06 | 0.12 | −0.05 | −0.05 |

| B | Standard error | Beta | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CM ~ DES + BSR + CRT | |||||

| (Intercept) | 40.65 | 2.53 | <0.001 | 35.67–45.62 | |

| DES | 0.44 | 0.05 | 0.29 | <0.001 | 0.34–0.54 |

| BSR | 4.37 | 0.86 | 0.16 | <0.001 | 2.69–6.05 |

| CRT | −2.36 | 0.55 | −0.14 | <0.001 | −3.44–−1.29 |

| HOAX ~ DES + EHEALS + BSR + CRT | |||||

| (Intercept) | 36.94 | 5.00 | <0.001 | 27.14–46.75 | |

| DES | 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.001 | 0.08–0.32 |

| eHEALS | −3.64 | 0.98 | −0.12 | <0.001 | −5.56–−1.72 |

| BSR | 0.91 | 1.06 | 0.03 | 0.39 | −1.17–2.99 |

| CRT | −3.61 | 0.68 | −0.18 | <0.001 | −4.94–−2.28 |

| CREATED ~ DES + EHEALS + BSR + CRT | |||||

| (Intercept) | 34.53 | 4.48 | <0.001 | 25.73–43.33 | |

| DES | 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.12 | <0.001 | 0.09–0.31 |

| eHEALS | −2.36 | 0.88 | −0.09 | <0.01 | −4.08–−0.64 |

| BSR | 2.64 | 0.95 | 0.09 | <0.01 | 0.78–4.51 |

| CRT | −3.97 | 0.61 | −0.22 | <0.001 | −5.16–−2.78 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pisl, V.; Volavka, J.; Chvojkova, E.; Cechova, K.; Kavalirova, G.; Vevera, J. Dissociation, Cognitive Reflection and Health Literacy Have a Modest Effect on Belief in Conspiracy Theories about COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5065. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105065

Pisl V, Volavka J, Chvojkova E, Cechova K, Kavalirova G, Vevera J. Dissociation, Cognitive Reflection and Health Literacy Have a Modest Effect on Belief in Conspiracy Theories about COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(10):5065. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105065

Chicago/Turabian StylePisl, Vojtech, Jan Volavka, Edita Chvojkova, Katerina Cechova, Gabriela Kavalirova, and Jan Vevera. 2021. "Dissociation, Cognitive Reflection and Health Literacy Have a Modest Effect on Belief in Conspiracy Theories about COVID-19" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 10: 5065. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105065

APA StylePisl, V., Volavka, J., Chvojkova, E., Cechova, K., Kavalirova, G., & Vevera, J. (2021). Dissociation, Cognitive Reflection and Health Literacy Have a Modest Effect on Belief in Conspiracy Theories about COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(10), 5065. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105065