Correlation between Elderly Migrants’ Needs and Environmental Adaptability: A Discussion Based on Human Urbanization Features

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Methods

2.1. Extraction of Urbanization Indicators for Elderly Migrants

2.2. Evaluation and Investigation of Environmental Adaptability

2.2.1. Sample

2.2.2. Investigation Process

2.3. Analytical Framework

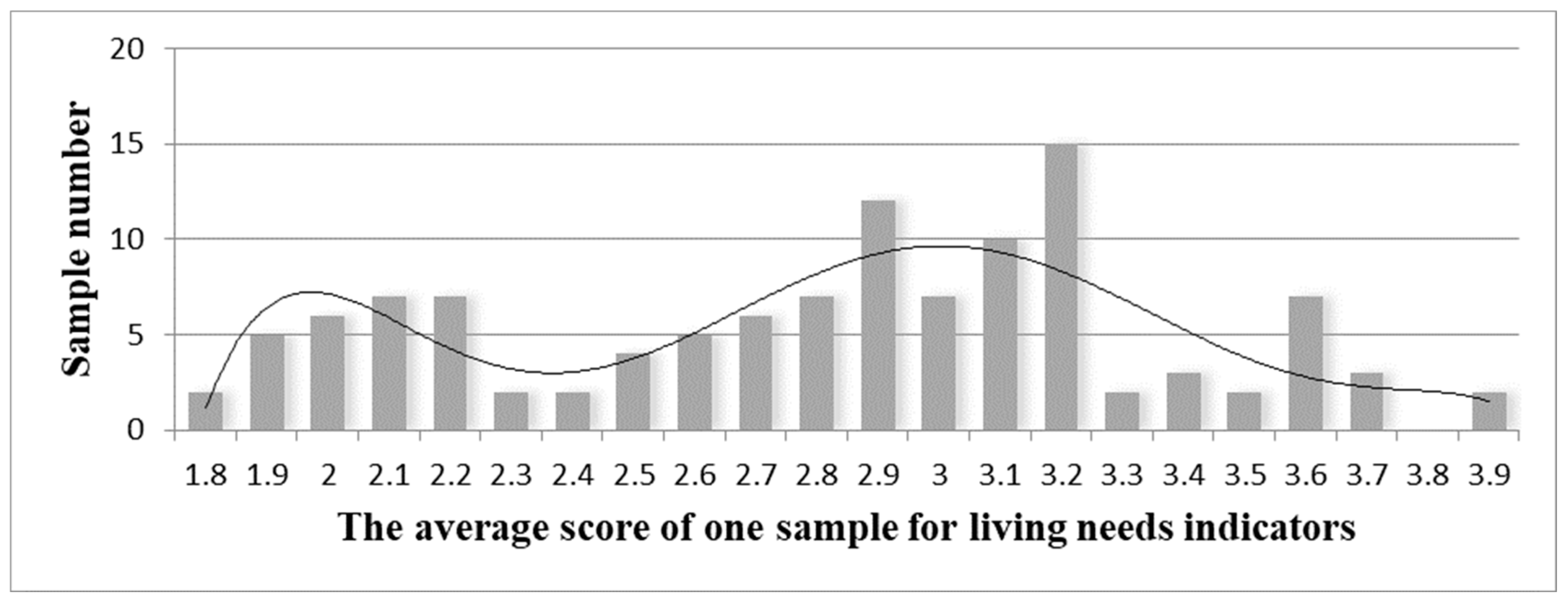

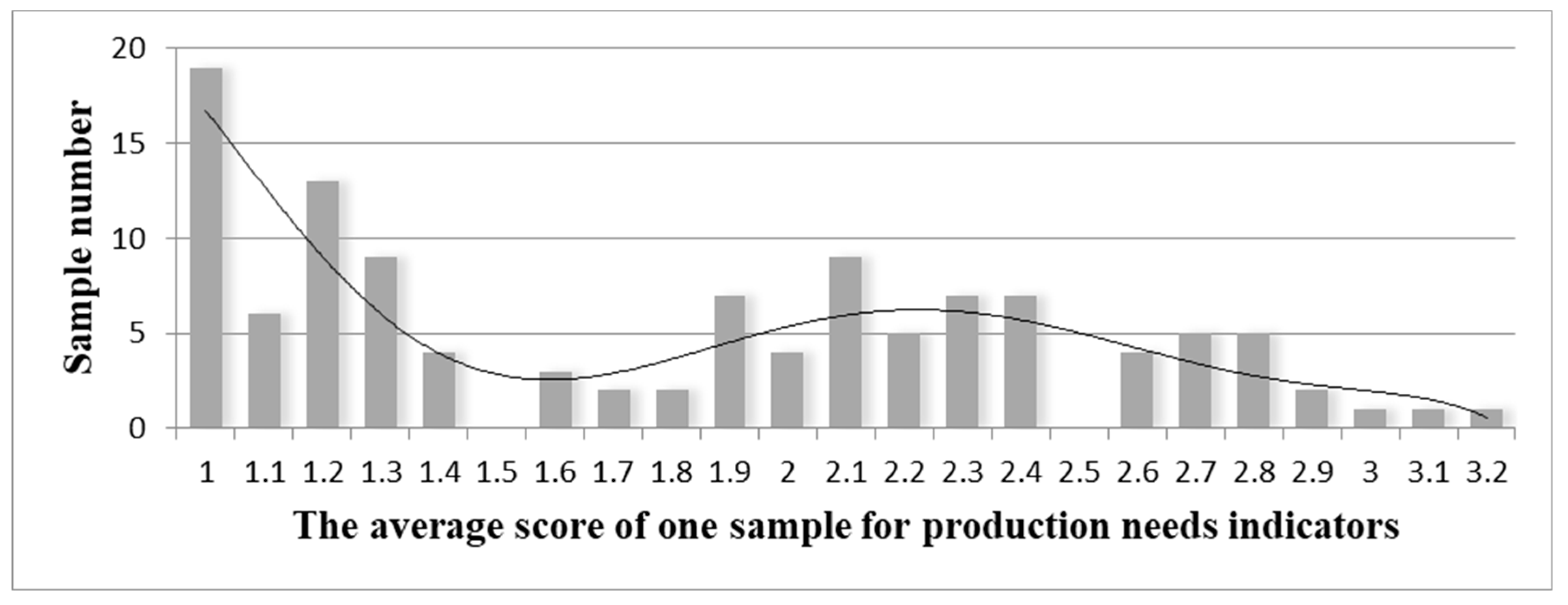

- Using hierarchical cluster analysis, which can classify samples according to the closeness degree without prior knowledge; with squared Euclidean distance and between-groups linkage, samples were respectively divided into two groups according to production and living need indicators. Taking the one-way ANOVA test, which can find whether the different levels of a control variable have a significant impact on the observed variable, to find need indicators with significant differences; comparing the average scores of the indicators with significant differences to determine which group is urbanized respectively in living and production dimension, and to assign urbanized values to the samples.

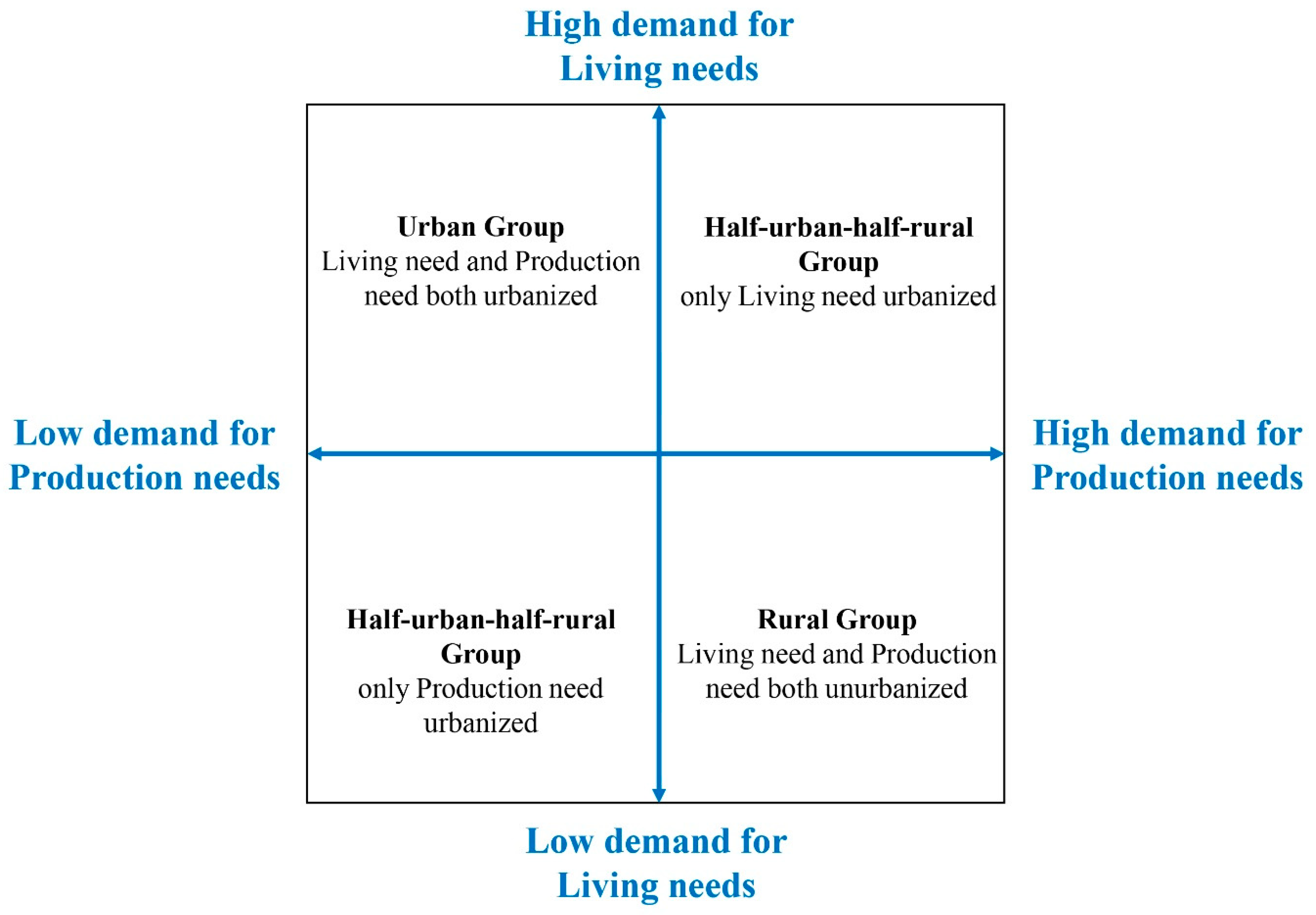

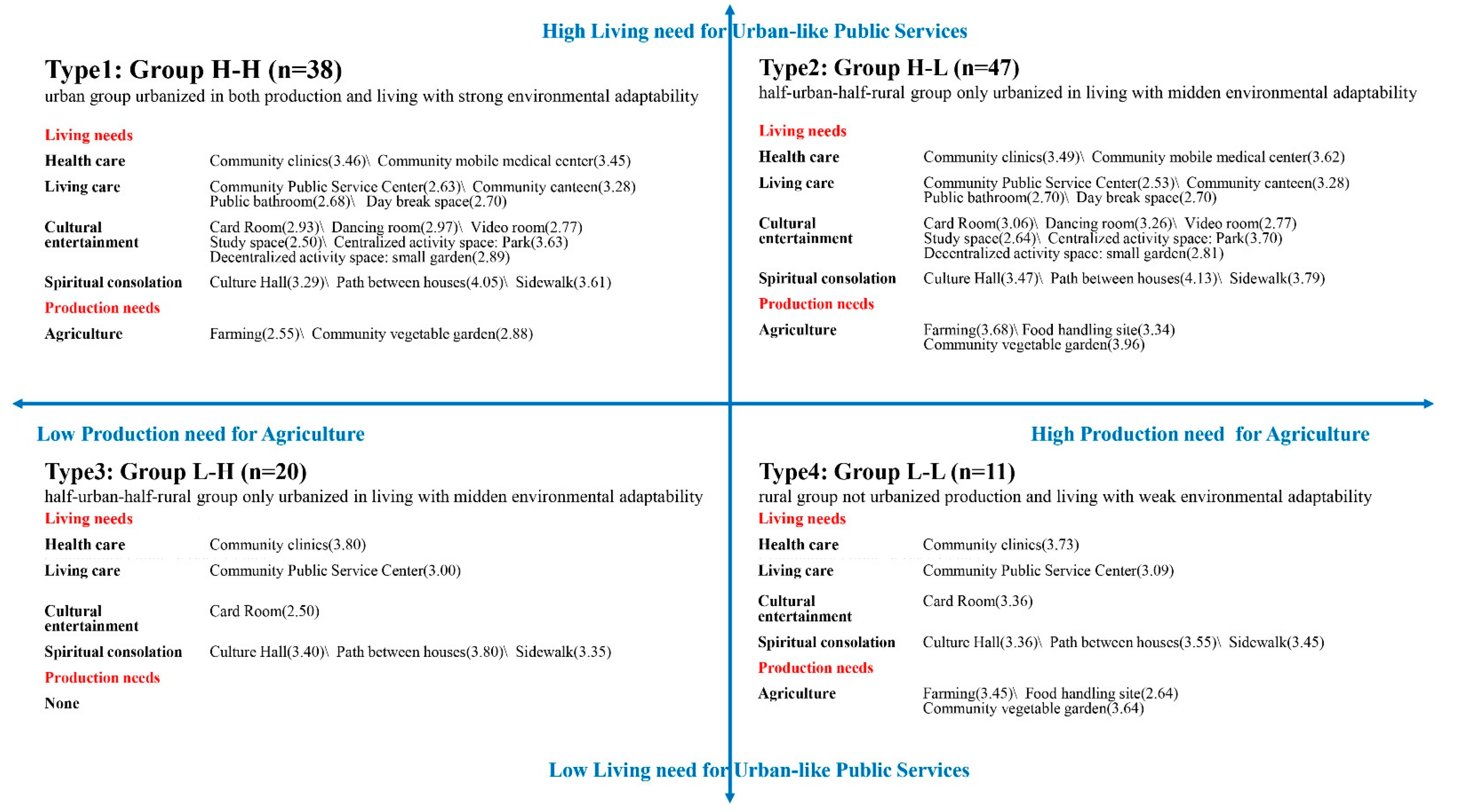

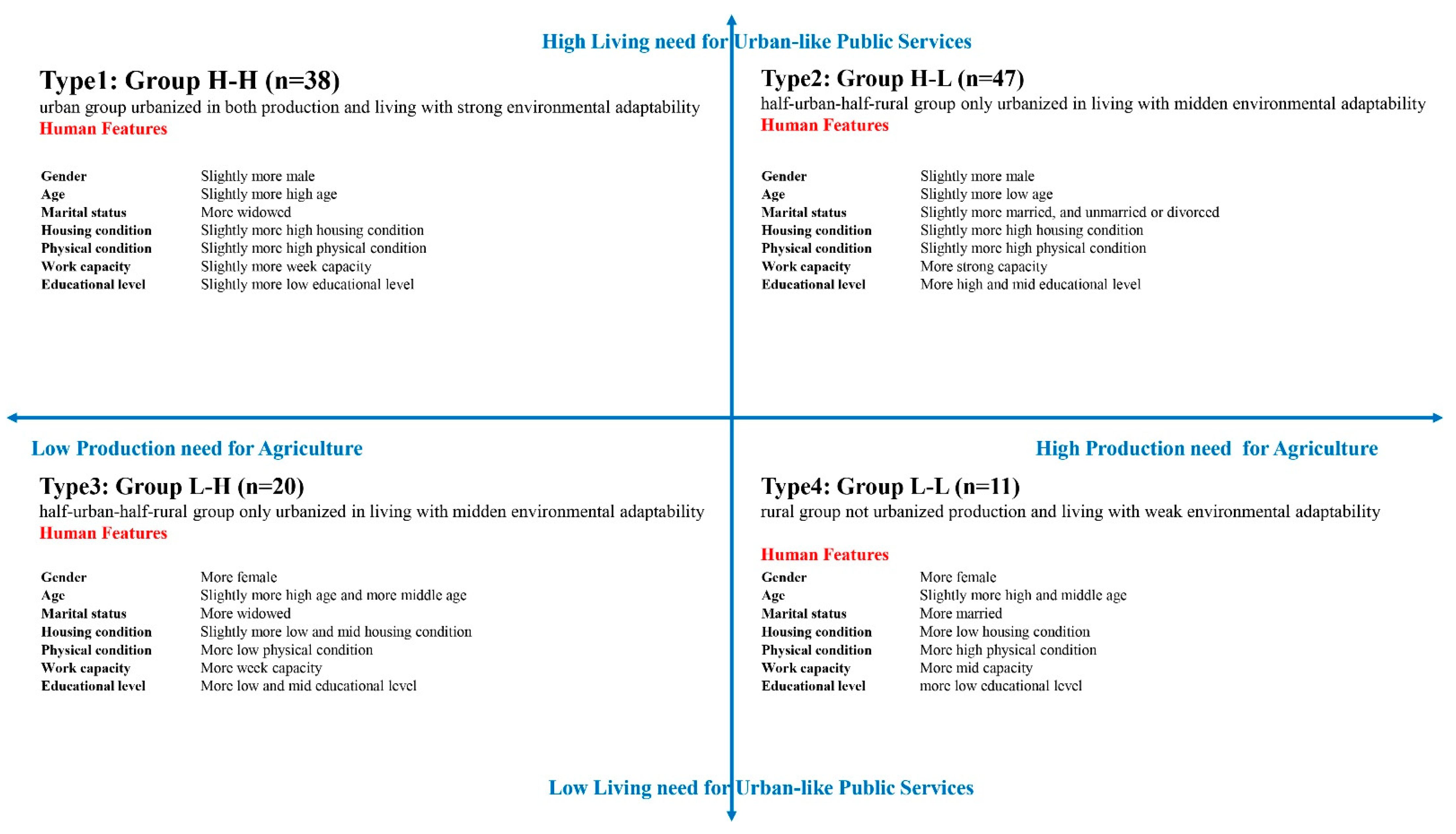

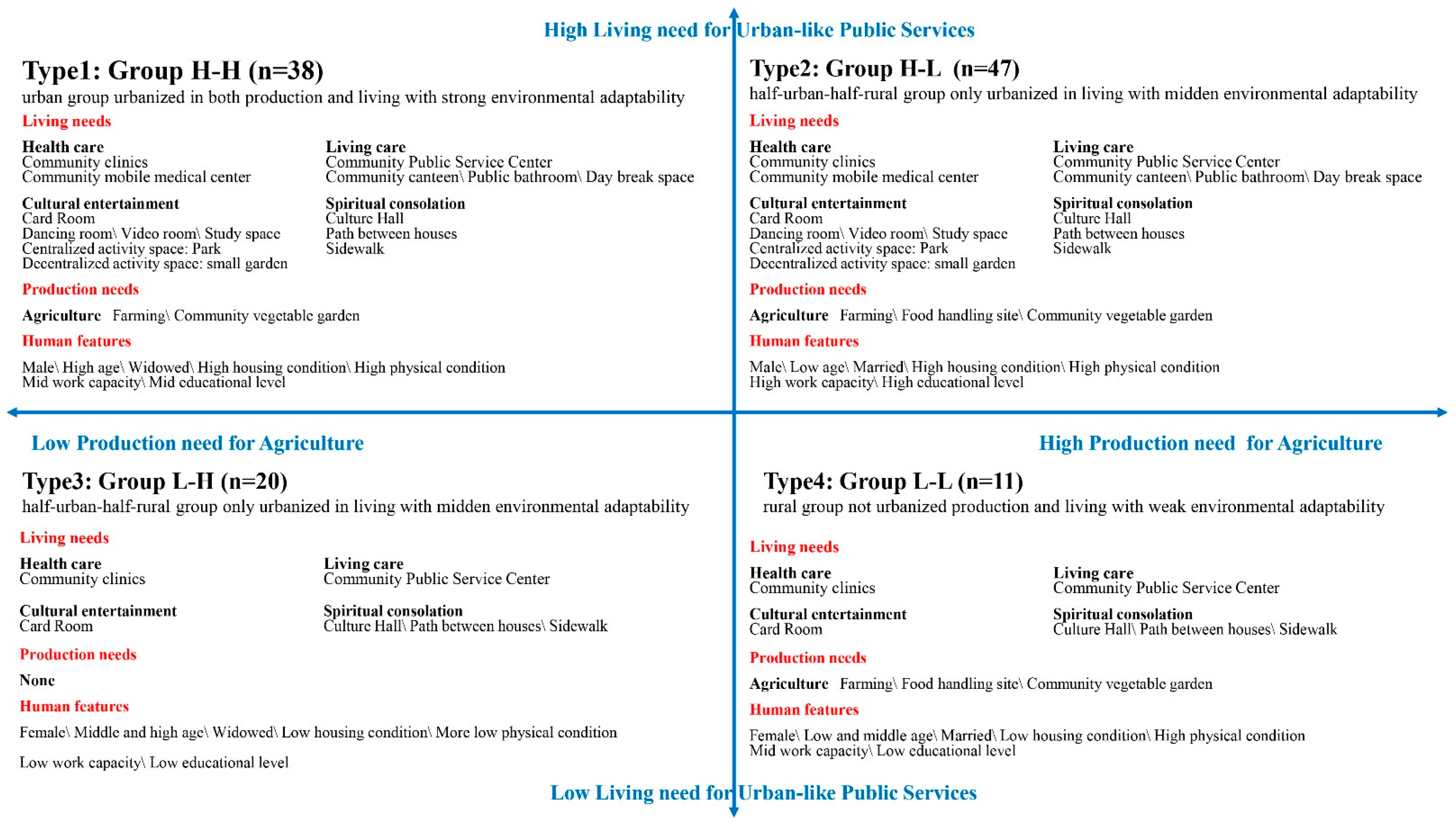

- According to living and production urbanized values, the study constructed a four-quadrant model frame on human urbanization feature as follows: an Urban Group with both living and production needs urbanized (Group H-H); a Half-urban-half-rural Group with only living needs urbanized(Group H-L); a Half-urban-half-rural Group with only production needs urbanized (Group L-H); and a Rural group with both living and production needs not urbanized (Group L-L) (Figure 3). Each group’ final need indicators are determined according to its average of every need score, with which a need-based urbanization decomposition model is established.

- Using the chi-square test, which can find the difference between the actual value and theoretical value of an observed variable for categorical control, the study compares the categorical percentage of individual characteristics with the overall percentage, and mines the significant difference of individual characteristics for four urbanization groups. Each group’ final individual characteristics are determined according to every individual percentage, with which an individual-characteristics-based urbanization decomposition model is established.

3. Results

3.1. Need-Based Classification of Urbanization Characteristics

3.2. Urbanization Types’ Characteristics of Environmental Adaptability

3.3. Correlation between Need and Environmental Adaptability

4. Discussion

4.1. Promote the Supply Level of Urban Public Services

4.2. Create a Place That Embodies the Spirit of Immigrants’ Homeland

4.3. Moderate Consideration of Agricultural Production Needs

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Sherbinin, A.; Castro, M.; Gemenne, F.; Cernea, M.M.; Adamo, S.; Fearnside, P.M.; Krieger, G.; Lahmani, S.; Oliver-Smith, A.; Pankhurst, A.; et al. Preparing for Resettlement Associated with Climate Change. Science 2011, 334, 456–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.; Hao, P.; Huang, X. Land conversion and urban settlement intentions of the rural population in China: A case study of suburban Nanjing. Habitat Int. 2016, 51, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Ley, D. Residential relocation and the remaking of socialist workers through state-facilitated urban redevelopment in Chengdu, China. Urban. Stud. 2019, 56, 2480–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Z.; Gu, M. Planning and practice of reservoir resettlement in new-type urbanization mode: Case of Nan’an Reservoir in Yongjia County of Wenzhou City. Yangtze River 2015, 46, 107–111. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lian, H.; Glendinning, A.; Yin, B. The Issue of ‘Land-lost’ Farmers in the People’s Republic of China: Reasons for discontent, actions and claims to legitimacy. J. Contemp. China 2016, 25, 718–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Qiu, Z. The usage pattern and spatial preference of community facilities by elder people in rural environments. Neth. J. Hous. Environ. Res. 2019, 35, 661–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bing, L.; Yue, L. The Change of Country Resident’ Behavior and Evaluation After Relocation. Archit. J. 2009, 64–68. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhi, Q.; Yi, H.; Yue, W.; Zhu, W. In Study on “Adapted Use” in Reservoir Resettlement Community—Taking Community L of Zhejiang Province as an Example, A New Idea for Starting Point of the Silk Road: Urban and Rural Design for Human. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Environment-Behavior Studies 2020, Xi’an, China, 17–18 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Z. Displaced villagers’ adaptation in concentrated resettlement community: A case study of Nanjing, China. Land Use Policy 2019, 88, 104097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schopp, K. Analyzing Coping Strategies and Adaptation after Resettlement—Case Study of Ekondo Kondo, Cameroon and Ekondo Kondo Model of Adaptation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aijang, C.; Guoqing, S. A Social Integration Study of Involuntary Migration. Chin. Sociol. Anthropol. 2006, 38, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Guo, M.; Li, S.; Feldman, M. The Impact of the Anti-Poverty Relocation and Settlement Program on Rural Households’ Well-Being and Ecosystem Dependence: Evidence from Western China. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2021, 34, 40–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Xiong, L. Evolution of the Physical and Social Spaces of ’Village Resettlement Communities’ from the Production of Space Perspective: A Case Study of Qunyi Community in Kunshan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Li, M. The Policy Information Gap and Resettlers’ Well-Being: Evidence from the Anti-Poverty Relocation and Resettlement Program in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B. Environment-Behavior Theories and Design Methodology. J. Hum. Settl. West China 2017, 32, 1–6. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, S.X.B. Re-examining China’s “Urban” Concept and the Level of Urbanization. China Q. 1998, 154, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarracín, D.; Wyer, R.S. The cognitive impact of past behavior: Influences on beliefs, attitudes, and future behavioral decisions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, D.; Wang, J. Basic Public Health Service Utilization by Internal Older Adult Migrants in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Tan, X. Educational Assortative Mating and Health: A Study in Chinese Internal Migrants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Hu, X.; Guo, X.; Lian, C. Risk Information Seeking Behavior in Disaster Resettlement: A Case Study of Ankang City, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, T.; Yuan, J.; Li, L.; Shao, Q.; Zheng, C. Demand for community-based care services and its influencing factors among the elderly in affordable housing communities: A case study in Nanjing City. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, B. Community Home-based Care Service for Urban Elderly: Demand Levels and Satisfying Strategy. Chin. Soc. Secur. Rev. 2019, 3, 147–159. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tong, W.; Lo, K.; Zhang, P. Land Consolidation in Rural China: Life Satisfaction among Resettlers and Its Determinants. Land 2020, 9, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.K.P.; Wong, F.K.Y.; Chan, K.L.; Wong, F.; Ho, H.C.; Wong, M.S.; Ho, Y.S.; Yuen, J.W.M.; Siu, J.Y.-M.; Yang, L. The Impact of the Environment on the Quality of Life and the Mediating Effects of Sleep and Stress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, A.E.; Cloutier, D.S. Elderly migration and its implications for service provision in rural communities: An Ontario perspective. J. Rural Stud. 1991, 7, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Rosenberg, M.W.; Wang, W.; Yang, L.; Li, H. Access to residential care in Beijing, China: Making the decision to relocate to a residential care facility. Ageing Soc. 2011, 32, 1277–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C. Towards “China’s Issues” with Interdisciplinary Approach Thinking in Organizing the Special Issue of “Architectural Anthropology”. Archit. J. 2020, 6, 1–4. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ley, D. The Immigrant Church as an Urban Service Hub. Urban. Stud. 2008, 45, 2057–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-S.F. Small Towns and China’s Urbanization Level. China Q. 1989, 120, 771–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Das, D. Quality of life among older adults in China and India: Does productive engagement help? Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 229, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Waley, P.; Gonzalez, S. ‘Nice apartments, no jobs’: How former villagers experienced displacement and resettlement in the western suburbs of Shanghai. Urban. Stud. 2017, 55, 3202–3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, Q.; Yi, H.; Yue, W.; Jiuyan, S.; Zhu, W. A Tentative Study of the Elderly Human Settlements in Urban-insertion Reservoir Resettlement Communitys. Archit. Cult. 2020, 10, 132–134. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liddell, T.M.; Kruschke, J.K. Analyzing ordinal data with metric models: What could possibly go wrong? J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 79, 328–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, J.; Bolano, D. Social and productive activities and health among partnered older adults: A couple-level analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 229, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halmdienst, N.; Radhuber, M.; Winter-Ebmer, R. Attitudes of elderly Austrians towards new technologies: Communication and entertainment versus health and support use. Eur. J. Ageing 2019, 16, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Ye, L.; Luo, W. Building for the Elderly in North Zhejiang Rural Areas Based on the Survey and Analysis of Demands. New Archit. 2017, 1, 24–28. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Qiu, Z. Exploring Daily Activity Patterns on the Typical Day of Older Adults for Supporting Aging-in-Place in China’s Rural Environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milbourne, P. Growing public spaces in the city: Community gardening and the making of new urban environments of publicness. Urban. Stud. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchecker, M. Withdrawal from the Local Public Place: Understanding the Process of Spatial Alienation. Landsc. Res. 2009, 34, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z. Resettlement and adaptation in China’s small town urbanization: Evidence from the villagers’ perspective. Habitat Int. 2017, 67, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Holstein, E. Strategies of self-organising communities in a gentrifying city. Urban. Stud. 2019, 57, 1284–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Kim, S.; Oh, J. Effect of household economic indices on sustainability of community gardens. J. Asian Arch. Build. Eng. 2019, 18, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First-Level Indicator | Second-Level Indicator | Third-Level Indicator |

|---|---|---|

| Living Needs | Health care | Community clinics |

| Community mobile medical center | ||

| Living care | Community public service center | |

| Community canteen | ||

| Public bathroom | ||

| Day break space | ||

| Overnight restroom | ||

| Cultural entertainment | Card room | |

| Dancing room | ||

| Video room | ||

| Study space | ||

| Centralized activity space: Park | ||

| Decentralized activity space: small garden | ||

| Spiritual consolation | Culture hall | |

| Path between houses | ||

| Sidewalk | ||

| Production Needs | Agriculture | Farmland |

| Parking for agricultural vehicles | ||

| Storage space for fertilizer and pesticide | ||

| Farm operation space | ||

| Community agricultural garden | ||

| Vegetable stall | ||

| Handmade and Business | Family workshop | |

| Street shop | ||

| Labor employment |

| Name | Option | Explanation | Frequency | Percent % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | / | 64 | 55.17 |

| Male | / | 52 | 44.83 | |

| Age | Low | 55–69 years | 49 | 42.24 |

| Mid | 70–79 years | 46 | 39.66 | |

| High | Older than 80 years | 21 | 18.1 | |

| Marital status | Married | / | 87 | 75 |

| Widowed | / | 26 | 22.41 | |

| Unmarried, divorced | / | 3 | 2.59 | |

| Pension | Low | Less than 1000 ¥ | 63 | 54.31 |

| Mid | 1000–2000 ¥ | 33 | 28.45 | |

| High | More than 2000 ¥ | 20 | 17.24 | |

| Housing condition | Low | Living with other family members, no house ownership | 14 | 12.07 |

| Mid | Living alone, no house ownership | 14 | 12.07 | |

| High | House ownership | 88 | 75.86 | |

| Physical condition | Low | Needing help or nursing | 7 | 6.03 |

| High | Self-caring | 109 | 93.97 | |

| Work capacity | Weak | Can neither undertake housework nor make money | 27 | 23.28 |

| Mid | Mainly housework | 62 | 53.45 | |

| Strong | Can make money | 27 | 23.28 | |

| Educational level | Low | Not completed primary education | 59 | 50.86 |

| Mid | Completed primary education | 42 | 36.21 | |

| High | Completed junior school education and above | 15 | 12.93 |

| Living Demand Indicators | Classification of Living Needs (Mean ± Standard Deviation) | Average Score (Mean ± Standard Deviation) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (n = 85) | 2 (n = 31) | |||

| Community clinics | 3.49 ± 0.84 | 3.77 ± 0.92 | 3.57 ± 0.87 | 0.124 |

| Community experts medical center | 3.48 ± 0.96 | 1.87 ± 0.62 | 3.05 ± 1.13 | 0.000 ** |

| Community public service center | 2.73 ± 0.90 | 2.87 ± 0.85 | 2.75 ± 0.93 | 0.450 |

| Community canteen | 3.31 ± 0.95 | 1.52 ± 0.72 | 2.83 ± 1.20 | 0.000 ** |

| Public bathroom | 2.69 ± 0.93 | 1.19 ± 0.40 | 2.30 ± 1.06 | 0.000 ** |

| Day break space | 2.72 ± 1.11 | 1.13 ± 0.56 | 2.29 ± 1.22 | 0.000 ** |

| Night rest space | 2.19 ± 1.20 | 1.03 ± 0.18 | 1.88 ± 1.15 | 0.000 ** |

| Card room | 2.95 ± 1.05 | 2.81 ± 1.22 | 2.91 ± 1.09 | 0.525 |

| Dancing room | 2.99 ± 1.32 | 1.03 ± 0.18 | 2.47 ± 1.43 | 0.000 ** |

| Video room | 2.79 ± 1.37 | 1.13 ± 0.43 | 2.34 ± 1.40 | 0.000 ** |

| Study space | 2.52 ± 1.29 | 1.16 ± 0.45 | 2.16 ± 1.28 | 0.000 ** |

| Centralized activity space: park | 3.66 ± 1.26 | 2.16 ± 0.97 | 3.26 ± 1.36 | 0.000 ** |

| Decentralized activity space: small garden | 2.91 ± 1.20 | 1.16 ± 0.37 | 2.44 ± 1.30 | 0.000 ** |

| Cultural hall | 3.32 ± 0.89 | 3.39 ± 1.12 | 3.34 ± 0.95 | 0.729 |

| Paths between houses | 4.08 ± 1.21 | 3.71 ± 0.82 | 3.97 ± 1.14 | 0.115 |

| Sidewalk | 3.64 ± 1.23 | 3.39 ± 0.76 | 3.58 ± 1.17 | 0.297 |

| Production Demand Indicators | Classification of Production Needs (Mean ± Standard Deviation) | Average Score (Mean ± Standard Deviation) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1′ (n = 58) | 2′ (n = 58) | |||

| Farming | 1.12 ± 0.38 | 3.64 ± 1.02 | 2.38 ± 1.47 | 0.000 ** |

| Parking lot for agricultural vehicles | 1.09 ± 0.28 | 2.03 ± 0.73 | 1.56 ± 0.72 | 0.000 ** |

| Storage space for fertilizer and pesticide | 1.05 ± 0.29 | 2.21 ± 1.02 | 1.63 ± 0.94 | 0.000 ** |

| Food handling site | 1.14 ± 0.44 | 3.21 ± 1.53 | 2.17 ± 1.52 | 0.000 ** |

| Community vegetable garden | 1.55 ± 0.92 | 3.90 ± 1.00 | 2.72 ± 1.51 | 0.000 ** |

| Vegetable stand | 1.16 ± 0.45 | 1.98 ± 1.07 | 1.57 ± 0.91 | 0.000 ** |

| Family workshop | 1.29 ± 0.56 | 1.57 ± 0.90 | 1.43 ± 0.76 | 0.050 |

| Street-facing stores | 1.19 ± 0.69 | 1.38 ± 0.67 | 1.28 ± 0.68 | 0.135 |

| Labor employment | 1.50 ± 0.82 | 1.31 ± 0.63 | 1.41 ± 0.73 | 0.165 |

| Name | Option | Percentage of Type of Urbanization (N) | Average Percentage | χ² | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1 (38) Urban Group Urbanized Both in Living and Production | Type 2 (47) Half-Urban-Half-Rural Group ONLY Urbanized in Living | Type 3 (20) Half-Urban-Half-Rural Group Only Urbanized in Production | Type 4 (11) Rural Group Not Urbanized Both in Living and Production | |||||

| Gender | Female | 44.7% | 48.9% | 80.0% | 75.0% | 55.2% | 8.768 | 0.033 * |

| Male | 55.3% | 51.1% | 20.0% | 25.0% | 44.8% | |||

| Age | Low | 29.0% | 63.8% | 20.0% | 36.4% | 42.2% | 26.108 | 0.000 ** |

| Mid | 36.8% | 31.9% | 50.0% | 63.6% | 39.7% | |||

| High | 34.2% | 4.3% | 30.0% | 0.0% | 18.1% | |||

| Marital status | Married | 63.2% | 83.0% | 70.0% | 90.9% | 75.0% | 13.773 | 0.032 * |

| Widowed | 36.8% | 10.6% | 30.0% | 9.1% | 22.4% | |||

| Unmarried, divorced | 0.0% | 6.4% | 0.00% | 0.0% | 2.6% | |||

| Pension | Low | 60.5% | 48.9% | 65.0% | 36.4% | 54.3% | 4.232 | 0.645 |

| Mid | 23.7% | 29.80% | 25.0% | 45.5% | 28.5% | |||

| High | 15.80% | 21.3% | 10.0% | 18.2% | 17.2% | |||

| Housing condition | Low | 10.5% | 6.4% | 25.0% | 18.2% | 12.1% | 21.474 | 0.002 ** |

| Mid | 2.6% | 10.6% | 15.0% | 45.5% | 12.1% | |||

| High | 86.8% | 83.0% | 60.0% | 36.4% | 75.9% | |||

| Physical condition | High | 97.4% | 97.90% | 75.0% | 100% | 94.0% | 15.434 | 0.001 ** |

| Low | 2.6% | 2.1% | 25.0% | 0.0% | 6.0% | |||

| Work capacity | Weak | 29.0% | 8.5% | 45.0% | 27.3% | 23.3% | 18.059 | 0.006 ** |

| Mid | 44.7% | 57.5% | 55.0% | 63.6% | 53.5% | |||

| Strong | 26.3% | 34.0% | 0.0% | 9.1% | 23.3% | |||

| Educational level | Low | 52.6% | 27.7% | 85.0% | 81.8% | 50.9% | 33.864 | 0.000 ** |

| Mid | 44.7% | 42.6% | 15.0% | 18.2% | 36.2% | |||

| High | 2.6% | 29.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 12.9% | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hua, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Luo, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z. Correlation between Elderly Migrants’ Needs and Environmental Adaptability: A Discussion Based on Human Urbanization Features. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5068. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105068

Hua Y, Qiu Z, Luo W, Wang Y, Wang Z. Correlation between Elderly Migrants’ Needs and Environmental Adaptability: A Discussion Based on Human Urbanization Features. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(10):5068. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105068

Chicago/Turabian StyleHua, Yi, Zhi Qiu, Wenjing Luo, Yue Wang, and Zhu Wang. 2021. "Correlation between Elderly Migrants’ Needs and Environmental Adaptability: A Discussion Based on Human Urbanization Features" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 10: 5068. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105068

APA StyleHua, Y., Qiu, Z., Luo, W., Wang, Y., & Wang, Z. (2021). Correlation between Elderly Migrants’ Needs and Environmental Adaptability: A Discussion Based on Human Urbanization Features. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(10), 5068. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105068