2.1. Theoretical Discussion

Social comparison theory refers to people continually make comparison with other people to assess their own opinions and abilities [

6]. The theory includes both upward and downward social comparisons [

7,

8]. Social comparisons to someone who is performing better can be regarded as an upward comparison, contrarily, social comparisons to someone who is performing worse can be regarded as a downward comparison. Early researches have shown that both upward comparison and downward comparison can result in either positive outcomes [

9,

10,

11] or impaired outcomes [

12,

13]. This theory also points out that self-evaluation is a powerful intrinsic motivator; as such, social comparisons are a common phenomenon [

6]. During the social comparison process, a range of emotional experiences emerge, which in turn trigger corresponding behaviors [

14,

15].

Protection motivation theory points out that external stimuli (such as pressure or threat) can prompt individuals to turn on the self-protection mechanism and then lead to the corresponding self-protection behavior [

16]. For instance, a research found out that the pressure of leaders in workplace will lead to the generation of negative emotions, and the negative emotions will lead to the self-protection mechanism of leaders and the implementation of harmful behaviors [

17]. Previous researches have supported that the ability of employees can be a major trigger for leaders’ negative emotions [

18,

19]. According to protection motivation theory, when leaders experience negative emotions or feelings, they will generate corresponding behaviors to protect themselves [

17].

2.2. Employee’s Leadership Potential and Leadership Ostracism Behavior

Employee’s leadership potential refers to the potential of junior employees to be developed into leaders [

20,

21]. Based on the analysis of 40 influential journal papers, scholars summarized the four dimensions of leadership potential as “analytical skills, learning agility, drive, and emergent leadership” [

3]. Current research on employee’s leadership potential tends to focus on identifying leadership potential [

3] and how such potential impacts the employees themselves and their colleagues [

4]. However, employees with leadership potential are an important resource within an organization and a critical promoter of sustainable growth; hence, they also have a significant impact on organization management.

Ostracism refers to employees’ perceived interpersonal deviance from their leaders and can be seen as intentional or unintentional ostracism, open or discreet neglect, rejection, and exclusion in the workplace [

22,

23]. Different sources of exclusion have different impacts on employee attitudes and work behaviors [

24]. Compared to other sources of exclusion, due to the significance of management positions in an organization and ownership of organizational resources, exclusion from managers was found to have a more prominent negative impact on the physical and mental health and work behaviors of employees. Based on previous literatures, the factors which can affect leadership ostracism behavior can be summed up in three main factors, which include factors of leaders [

25,

26], factors of ostracized employees [

18,

19], and factors of organizations [

27]. Because employees with high leadership potential have a significant impact on organizations and leaders, this study focuses on exploring one of the factors of ostracized employees—employee’s leadership potential’s effect on leadership ostracism behavior.

The majority of existing studies suggest that low-performing and undervalued employees are more likely to suffer ostracism [

5]. However, employees with leadership potential may also be the target of ostracism or even suppression from managers due to their outstanding performance. It is possibly because the employees or the informal leaders with high leadership potential can be strong competitors for leaders’ status and power [

18]. This kind of unfavorable social comparison could make leaders perceive the lack of power and regard the employees with high leadership potential as a threat to their authority and position [

19]. According to the conservation of resources theory [

28], individuals have a tendency to preserve, protect, and obtain resources; moreover, when they expect resources to be threatened, individuals are likely to use existing resource reserves to adopt active adaptive strategies to prevent the further loss of resources. As conditional resources, managers’ status in an organization and corresponding authority give them the ability to control and influence others [

29]. When a manager perceives that his or her status or power is threatened, he or she may manifest coercive and negative behaviors with the expectation to restore status and power [

30]. Employee’s leadership potential is likely to be perceived as a threat to a manager’s status and power and may thus trigger corresponding action. The leaders may neglect and alienate the employees, impede employee’s promotion, reduce training opportunities, and perform other ostracism behavior to hinder this employee’s further success. Hence, based on the above analysis, hypothesis 1 was proposed:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Employee’s leadership potential positively affects leadership ostracism behavior.

2.3. The Mediating Role of Leader’s Envy

Managers enjoy privileges and advantages alongside their status in an organization. The benefits obtained by managers include valuable extrinsic rewards, autonomy in decision-making, control of resources, and opportunities to connect with external power holders [

31,

32]. These benefits are drivers that motivate many individuals to pursue managerial positions [

33]. Despite the inherent advantages of managerial roles, evidence suggests that managers also envy subordinates [

18,

34,

35]. Envy is most likely to occur when subordinates have strong social skills, show leadership potential, have close relationships with senior management, and are considered to be the main source of corporate innovation and progress [

36].

According to social comparison theory, self-evaluation is a powerful intrinsic motivator; as such, social comparisons are a common phenomenon [

6]. During the social comparison process, a range of emotional experiences emerge, which in turn trigger corresponding behaviors [

14,

15]. Specifically, positive emotions trigger pro-social behaviors, while negative emotions trigger antisocial behaviors in an organization [

37]. Studies have found that unfavorable upward social comparison is more likely to cause feelings of envy. Specifically, while forming comparisons, it is more common to develop feelings of envy toward individuals that are similar to oneself but have certain advantages in key areas [

38,

39,

40,

41]. As a double-faceted emotional variable, envy not only highlights what an individual lacks in him or herself (own disadvantages), but also what the compared party has that oneself does not (advantages of the compared party). Focusing on one’s own disadvantages may lead to self-abasement and negative emotions, whereas focusing on the advantages of others may lead to the evaluation that the compared party is not worthy of having such advantages, thereby leading to feelings of aversion and anger [

42].

Due to the prevalence of social comparisons, and in order to evaluate power and status, it is logical that managers are also making social comparisons with their subordinates, especially subordinates that are seen as superior to others, such as those with high leadership potential. Furthermore, empirical data have shown that adverse downward comparisons are common in the workplace and trigger feelings of envy, and leaders tend to make downward comparison with employees that possess specific superior qualities [

18,

35,

36]. Subordinates with superior qualities can be defined as having strong social skills, the potential to become leaders, good relationships with senior managers, or as sources of innovative ideas [

36]. The adverse social comparison between leaders and employees could make leaders perceive the lack of power and regard the employees with high leadership potential as a threat to their authority and position and leads to the feelings of envy and insecurity [

19]. For that reason, it can be assumed that, during the process of social comparison between managers and employees, employees’ display of leadership potential may trigger downward feelings of envy in their leaders. Such downward envy is reflected as envy toward both the specific quality and the employee. Hence, the following hypothesis was proposed:

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Employee’s leadership potential has a positive effect on leader’s envy.

According to the definition proposed by Parrott and Smith [

43], envy occurs when an individual perceives that he or she lacks a superior quality, achievement, or possession that is possessed by others. Envy stemming from social comparison is a distressing experience that threatens a person’s self-concept. Research has found that envy can lead to harmful behavior toward the object of one’s envy. In addition, someone may attempt to suppress the other party through certain behaviors and to reduce the perceived dissonance between the compared party and oneself [

14,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48]. Based on protection motivation theory [

16,

17], fear and negative emotions are generated when an individual feels threatened, which may initiate a self-protection mechanism that leads to corresponding protective behaviors. Therefore, the present authors proposed that leader’s envy could be used as a positive predictor for ostracism. Specifically, when a manager envies his or her subordinate, he or she is more likely to adopt harmful behaviors, such as ostracism, as a self-defense mechanism. Hence, based on the discussion above, hypothesis 3 was proposed:

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Leader’s envy has a positive effect on leadership ostracism behavior.

According to the previous discussions, it can be displayed that the leaders may feel envy when they make an unfavorable social comparison with the high leadership potential employees, and leads to leadership ostracism behavior further. Hypothesis 2 discussed the positive relationship between employee’s leadership potential and leader’s envy. Hypothesis 3 discussed the positive relationship between leader’s envy and leadership ostracism behavior. Therefore, based on Hypothesis 2 and Hypothesis 3, we further suggested that employee’s leadership potential stimulates the envy of their leaders, leading leaders to ostracize their employees as a means of self-protection; hence, employee’s leadership potential would cause leader’s envy, which thereby leads to leadership ostracism behavior. Thus, the following hypothesis was proposed:

Hypothesis 4 (H4). Leader’s envy mediates the relationship between employee’s leadership potential and leadership ostracism behavior.

2.4. The Moderating Role of Employee’s Political Skills

Nevertheless, not all employees with high leadership potential trigger envy from their leaders. Situational factors, such as organizational culture, and individual factors, such as employee and manager personality traits, also affect the relationship between employees’ leadership potential and leader’s envy. From the perspective of organizational politics, the present authors see political skills as individual characteristics that significantly affect the relationship between employees’ leadership potential and leader’s envy.

Political skills refer to the ability to effectively understand others in the workplace and to utilize such knowledge to create influence that strengthens individual or organizational goals [

49]. According to Ferris, Treadway, Kolodinsky, Hochwarter, Kacmar, Douglas and Frink [

49], political skills include the following four dimensions: apparent sincerity, social astuteness, interpersonal influence, and networking ability. The four dimensions have their own distinctive constructs yet are correlated to one another. Individuals that master the skill of apparent sincerity give the appearance of being honest, kind, and trustworthy, which affects the intentions or motives for their behaviors as perceived by others. Social astuteness refers to the ability to astutely observe other individuals and oneself, as well as to accurately interpret and analyze the behavior of others. Interpersonal influence tends to give the impression of having a humble, pleasant, and convincing personal style, which exerts a strong influence over others and oneself. Networking ability refers to the skill of identifying, developing, and utilizing various relationship networks.

Scholars point out that individuals with more political skills are better able to accurately interpret social situations and adjust their behavior, accordingly, choosing appropriate methods and strategies to influence others [

49,

50,

51]. According to Mintzberg [

52], individuals with more political skills are better at influencing others through persuasion, manipulation, and negotiation. Therefore, employees with more political skills are more likely to understand and perceive the potential negative impact of their leadership potential on their leaders, such as potential negative emotions and behaviors. Hence, it is reasonable to believe that they would be better at using such knowledge to avoid potential risk and problems by taking different measures to achieve personal or organizational goals. Employees with high leadership potential and more political skills should; therefore, be able to perceive the impact of such potential and take corresponding measures to avoid negative outcomes (such as leader’s envy), by demonstrating their value without triggering a loss of pride from managers, or by using persuasion and consultation to communicate their viewpoints to ensure support from their leaders. Thus, when employees exert political skills, their high leadership potential should be less likely to lead to envy, thereby reducing the likelihood of ostracism. Thus, hypothesis 5 was proposed:

Hypothesis 5 (H5). Employee’s political skills negatively moderate the impact of employee’s leadership potential on leadership ostracism behavior via leader’s envy. Specifically, employees with more political skills are less likely to lead to the indirect impact that their leadership potential has on ostracism via leader’s envy.

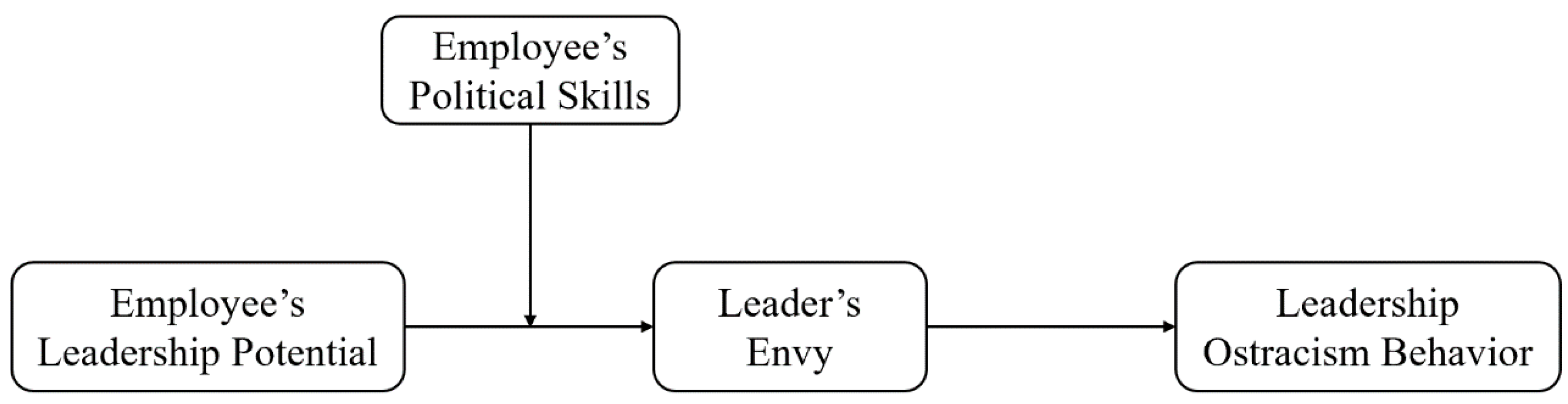

According to the discussion above, the following conceptual model has been conducted (See

Figure 1).