Our century is characterized by rapid and incessant economic change. Knowing how to adaptively respond to change not only defines the longevity and success of an organization [

1,

2] but also ensures organizational well-being in line with the sustainable development goals defined by the UN [

3]. In this sense, primary prevention interventions to build individuals’ strengths, such as the ability to adapt and promote change, as well as to reduce risks, are fundamental [

4,

5,

6]. Even if change is crucial to adaptively cope with modern phenomena, such as globalization and unstable labor markets [

7,

8], change could be experienced by individuals as stressful and undesirable. Even though resistance to change is a natural part of the change process [

9], the ability and willingness of individuals to adapt to organizational change differs [

10]. Some studies suggest that loss of control due to change is one of the major causes of resistance [

11]. Indeed, the feeling of losing control over life and work situations due to change (i.e., performing outside of a well-defined and familiar framework) can push individuals to oppose change. Lack of psychological resilience can hinder change processes too, since individuals with a low psychological resilience have worse coping strategies than their peers [

12]. Change implies more work in the short term (i.e., learning and adjustments are required to adapt to new tasks) and people, especially those with a low psychological resilience, are reluctant to undergo the required adjustments [

13]. Moreover, personality traits differences in resistance to change have been assessed by the scientific literature. For instance, if dogmatism emerged to predict individuals’ acceptance to change [

14] in the past, more recent works have focused on emotional stability (i.e., emotionality, neuroticism) and extraversion traits [

15,

16]. These studies report that extraversion scores were negatively related to resistance to change scores, while emotionality (i.e., the tendency to experience anxiety in response to life’s stresses), appeared to be positively related with individuals’ reluctance to accept organizational changes. The existence of such relationships is not surprising since individuals with a high score on emotionality traits experience anxiety in response to life’s stresses [

17]. Thus, changes within organizations could increase their levels of insecurity and produce further stress [

16]. Extraversion, instead, is characterized by a high need for stimulation and extraverted individuals are more likely to welcome change than to resist it, i.e., they experience more positive emotions in relation to change [

17,

18]. Despite the evidence that links individuals’ dispositions, such as emotionality and extraversion, with workers’ resistance to change, personality is an intrinsic psychological feature that is unlikely to change over time. Traditionally, it has been considered as stable [

19], not increasable through specific training. For this reason, the scientific literature regarding change dynamics within organizations, in line with the primary prevention approach, has recently considered other constructs and dynamics to facilitate interventions [

20]. Traditionally, prevention is articulated in three levels: Primary prevention, secondary prevention, and tertiary prevention [

21]. Primary prevention is focused on both avoiding the emergence of a problem before it begins and on promoting strengths. Secondary prevention regards early interventions when symptoms first emerge. Tertiary prevention aims to decrease symptoms and to support the functional recovery of the individual. The preventive perspective is more effective when the efforts to decrease risks are combined with the efforts to increase resources [

5,

6]. Primary prevention is particularly focused on building resources for individuals [

4,

5,

6,

22,

23]. In this sense, in a constantly changing world, negotiation processes are crucial in organizations. Having new resources to reduce resistance to change could lead to a lower risk of failure for the negotiation processes [

24,

25].

Negotiation is an important area of research for organizational management [

26] and can be defined as a decision-making form in which two or more parties interact with each other to resolve their opposing interests [

27]. The following conditions are necessary to realize a negotiation process [

28]: There are two or more parties (individuals, groups, organizations); there is a conflict between the needs and expectations of the parties; the parties choose to negotiate; there is the activation of a “give and take” process (the parties are willing to modify statements and initial requests to reach an agreement); and the parties prefer to negotiate to find an agreement instead of opposing. Change emerges as a pivotal condition for the negotiation process that seeks to reach an agreement among the different parties. In the literature, it is possible to distinguish between two perspectives [

29]: Negotiation for win or distributive bargaining; and integrative negotiation or negotiation to grow. Negotiation for win or distributive bargaining regards bargaining situations that distribute, spread, or divide resources among the parties involved, with a perspective of constant or zero-sum power. Integrative negotiation, or negotiation to grow, is a decision-making process in which two or more parties interact to resolve or manage their opposite interests, with a perspective of variable sum power. The second form of negotiation, variable sum negotiation, is preferable to distributive because integrative builds long-term relationships (e.g., trust increased) and thus, facilitates working together in the future [

30]. However, indications on how to conduct a negotiation that reduces resistance to change are scarce, at least regarding which type of communication is more effective and appropriate [

31,

32,

33]. The Psychology of Harmony and Harmonization [

34] asks instead for people’s relationality aspects which may be crucial in realizing harmony between individuals in different contexts, and the workplace is no exception.

Humor appears to be a resource which can be used to overcome resistance to change [

35,

36]. However, not all the humor styles enhance an openness towards change. Indeed, it has been reported by the scientific literature that a difference between potentially adaptive and beneficial functions of humor and the use of humor can be detrimental to well-being [

15,

37,

38]. Aggressive humor (i.e., the expression of humor without regard for its potential impact on others) and self-defeating humor (i.e., excessively self-disparaging humor) appear to increase resistance to change. Differently, affiliative humor (i.e., the use of humor to facilitate relationships) and self-enhancing humor (i.e., the capability to maintain a humorous perspective even in the face of stressors) appear to benefit the change process [

39].

The article is organized as follows: First, the aim of the study is defined, and the hypotheses developed is based on the literature. Then, in the “Methods and Procedure” section information about the participants, their recruitment, the measures employed, and the data collection procedure are presented. In the Results section, both descriptive and inferential analyses are described. Finally, the discussion follows highlighting the strengths and limitations of the study.

Aim of the Study and Hypotheses Development

The present study tests whether humor styles can mediate the relationship between personality traits (i.e., extraversion and emotionality) and individuals’ resistance to change. Indeed, evidence in the literature links humor styles with both personality traits and resistance to change. Nevertheless, none of the previous studies have considered the relationships of these three variables at the same time. First, we will test the assumption for mediation analysis by extending the literature results regarding the relation between emotionality and extraversion traits and resistance to change [

15,

16] by employing the HEXACO model of personality traits, which on the contrary has never been tested together with resistance to change. Starting from the Eysenck three-factor model of personality [

42,

43], and passing through the well-known and established Five-Factor model [

44,

45], the HEXACO model of personality can be conceived as the most evolved and updated conceptualization of personality [

17,

46].

Despite the lack of evidence, based on the Five-Factor model of personality, we can draw a link between emotionality and extraversion traits and resistance to change [

15,

16]. In particular, the emotionality trait should be positively associated with resistance to change (H2), while extraversion negatively (H5).

The relationship between the HEXACO model of personality traits and humor styles as defined by Martin et al. [

39] has been only tested once [

47]. Referring to this study, we hypothesized that emotionality could be negatively associated with self-enhancing humor (H1). The extraversion trait should instead be positively correlated with both affiliative (H3) and self-enhancing humor (H4).

As for the connection between humor and resistance to change, no other work tested it referring to the model of humor by Martin et al. Previous literature regarding other models stressed the role of “adaptive” humor in reducing resistance to change [

35,

39]. Thus, we transposed this evidence to the model of humor by Martin et al. in formulating our hypotheses, considering self-enhancing and affiliative humor styles as an “adaptive” form of humor. Consequently, we expected a positive correlation between resistance to change and both self-enhancing (H6) and affiliative (H7) humor styles, while no relationship is expected regarding “maladaptive” humor styles (H11).

Finally, given the expected relationships, in this study we will also construct mediation models using personality traits as predictors (i.e., emotionality and extraversion), humor styles as mediators (self-enhancing and affiliative humor), and individuals’ resistance to change as outcome variable (H9 and H10). The exploration of the mechanisms through which the HEXACO model of personality traits (causal variables) affects resistance to change (both directly and indirectly) has never been tested so far in the literature.

In the end, the following hypotheses were formulated:

H1:

Emotionality is negatively correlated with self-enhancing humor.

H2:

Emotionality is positively correlated with individuals’ resistance to change.

H3:

Extraversion is positively correlated with affiliative humor.

H4:

Extraversion is positively correlated with self-enhancing humor.

H5:

Extraversion is positively correlated with individuals’ resistance to change.

H6:

Self-enhancing humor is negatively correlated with resistance to change.

H7:

Affiliative humor is negatively correlated with resistance to change.

H8:

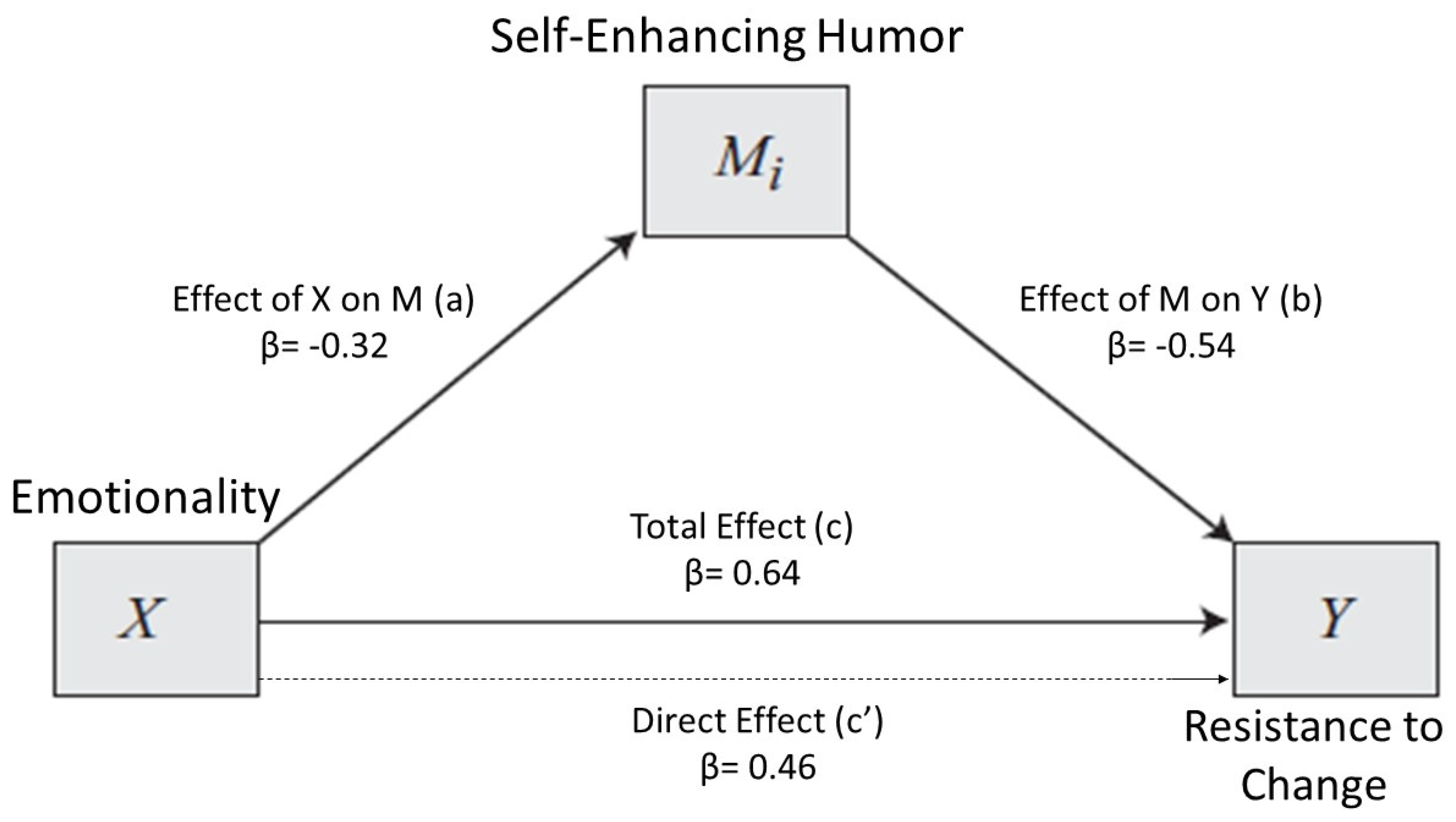

Self-enhancing humor mediates the effect of emotionality on individuals’ resistance to change.

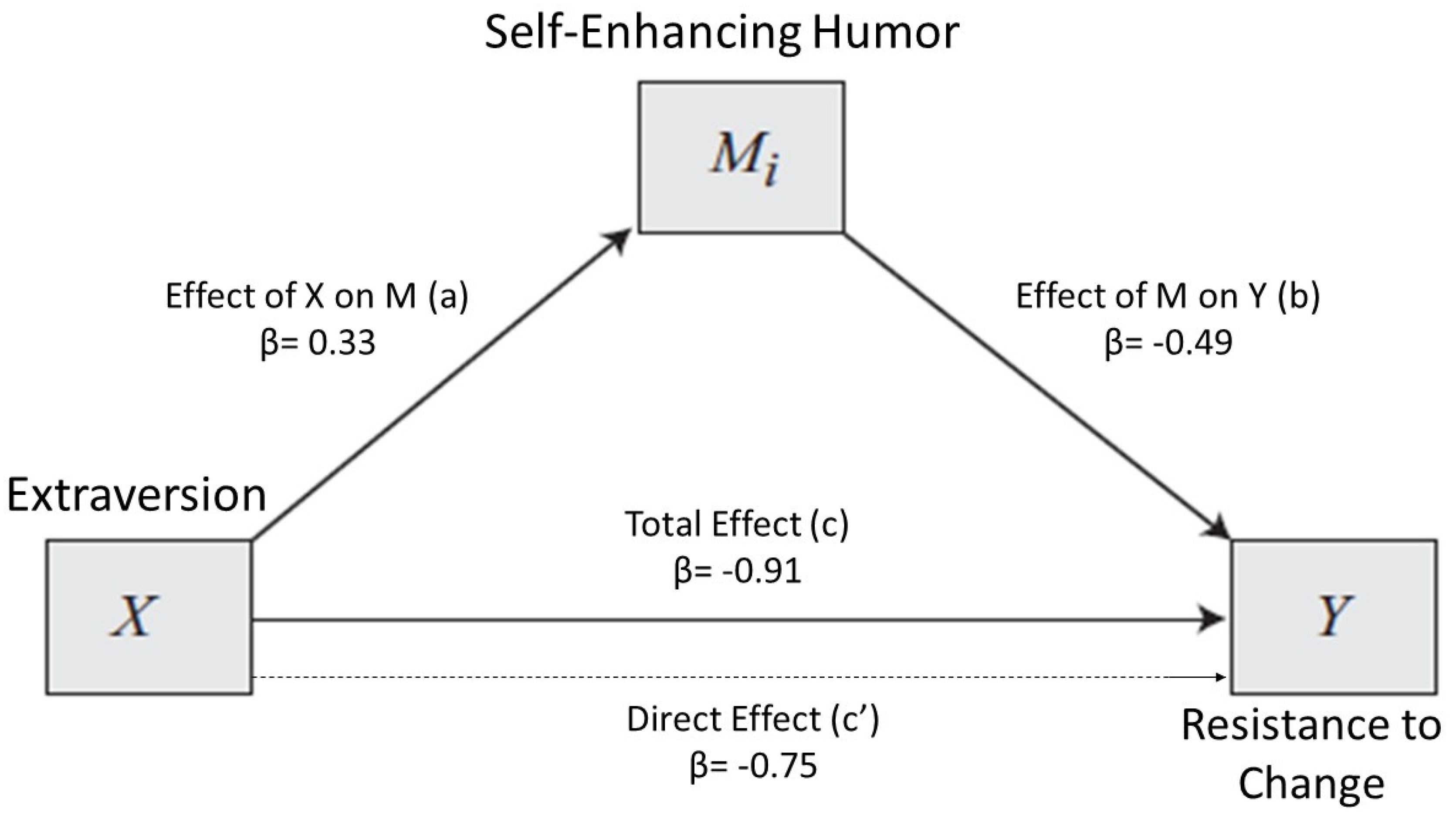

H9:

Self-enhancing humor mediates the effect of extraversion on individuals’ resistance to change.

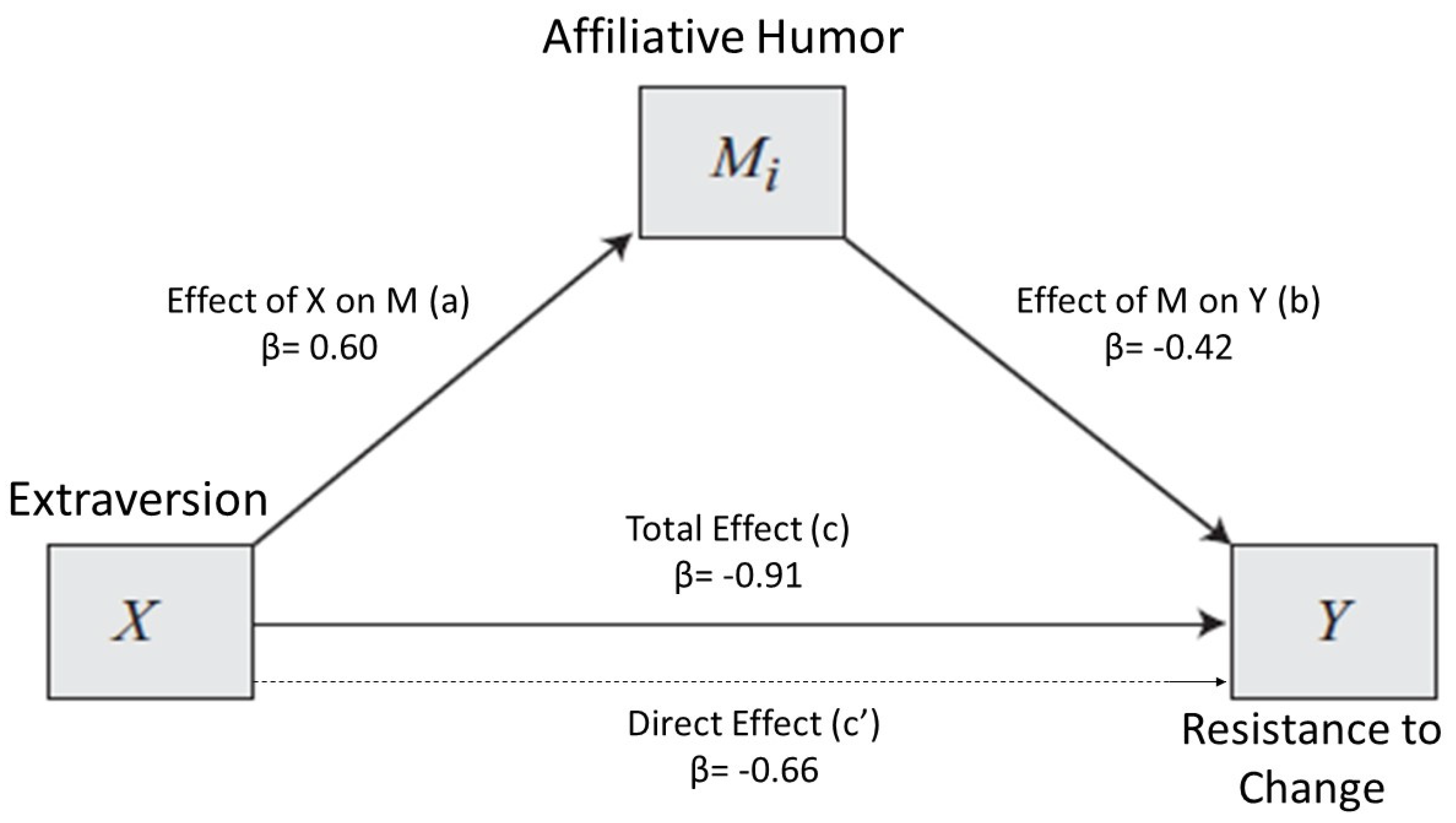

H10:

Affiliative humor mediates the effect of extraversion on individuals’ resistance to change.

H11:

Aggressive humor and self-defeating humor are not able to mediate the relationship between the personality traits considered (i.e., emotionality and extraversion) and resistance to change.