How to Form Wellbeing Perception and Its Outcomes in the Context of Elderly Tourism: Moderating Role of Tour Guide Services

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Wellbeing Perception (WBP)

2.2. Brand Prestige

2.3. Consumer Attitude

2.4. WOM

2.5. The Moderating of Tour Guide Services

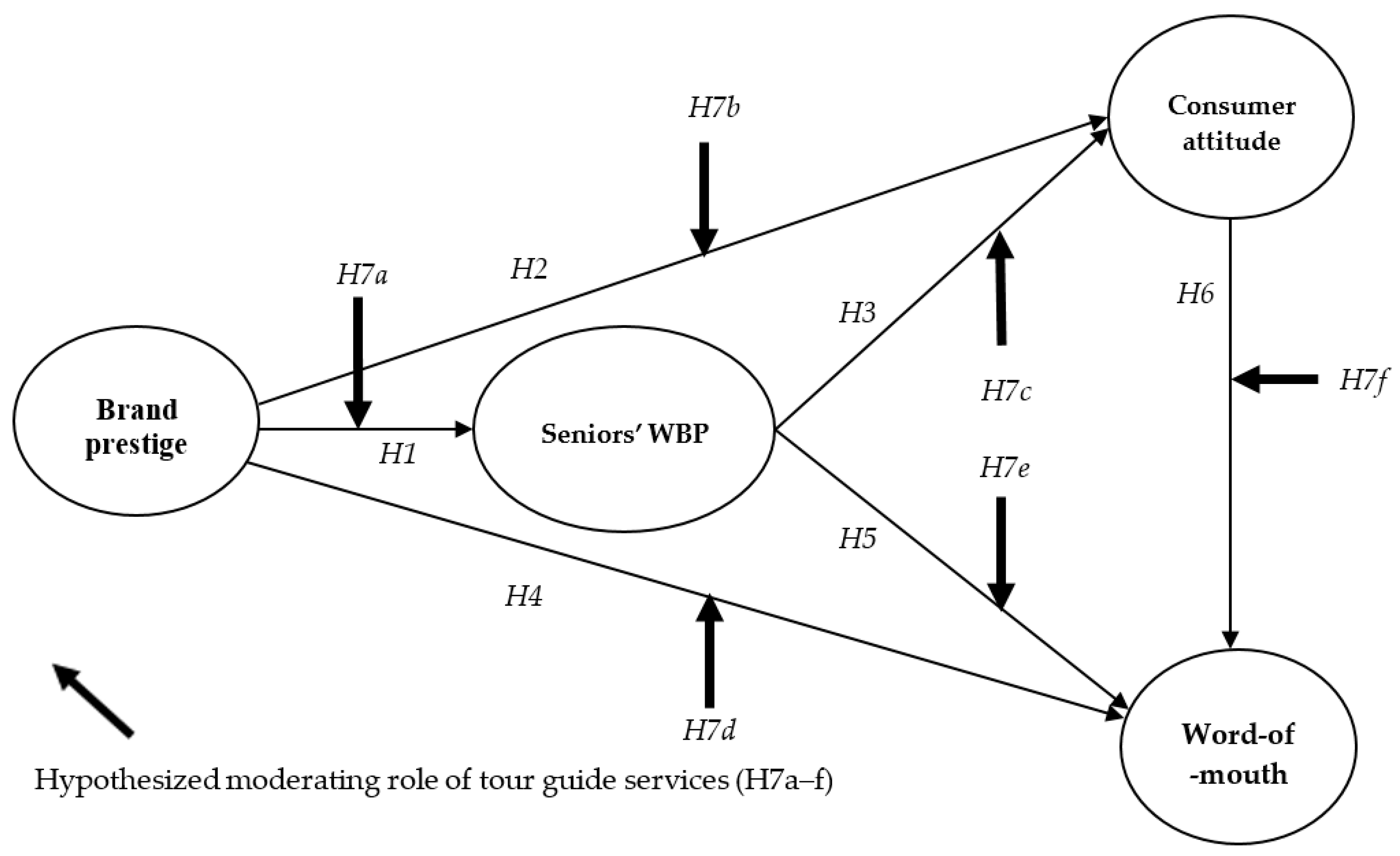

2.6. Proposed Conceptual Model

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Measurement

3.2. Data Collection

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

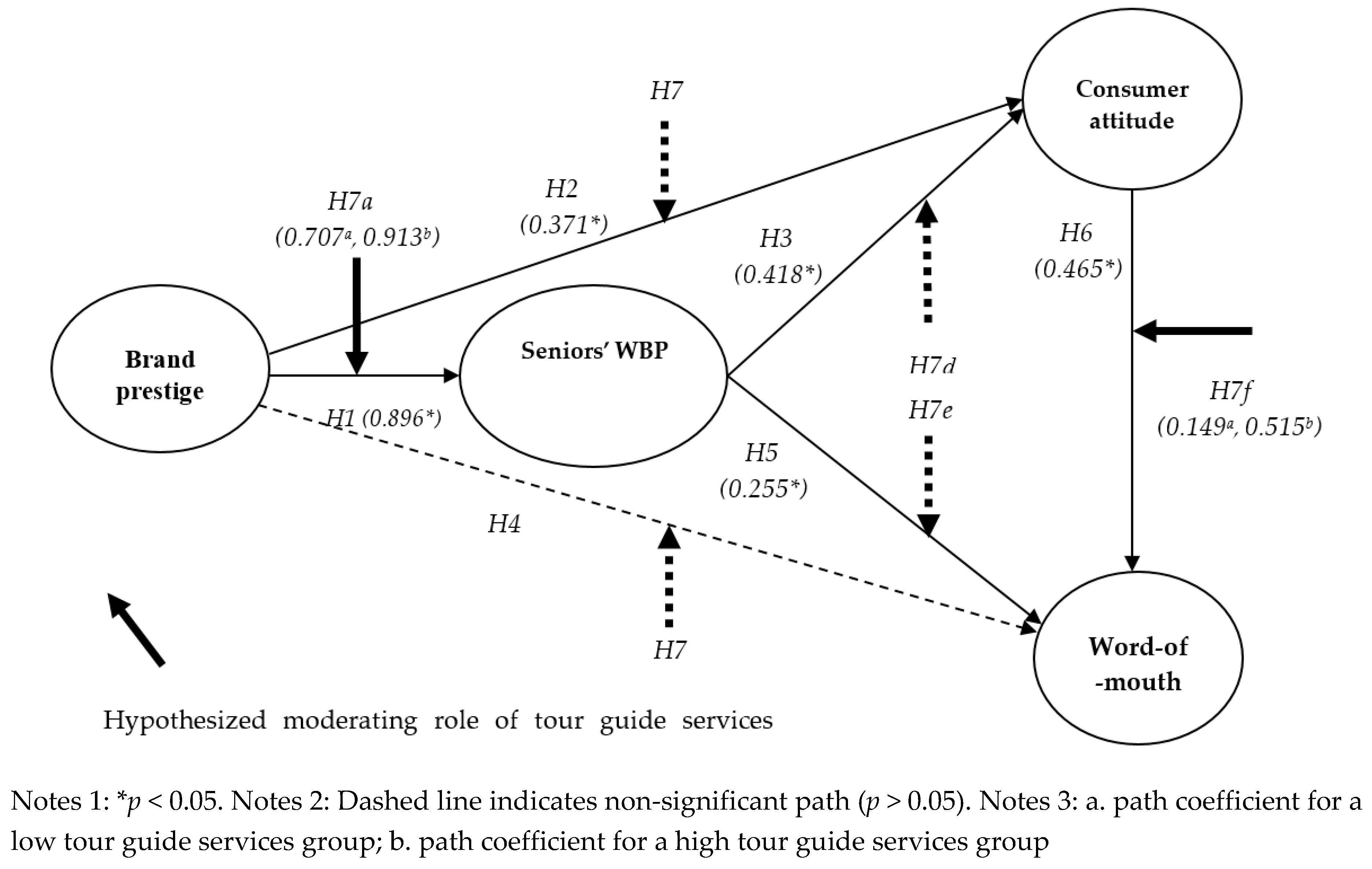

4.3. Structural Model

4.4. Moderating Role of Tour Guide Services

5. Discussions and Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statistics Korea. Elderly People Statistics. Available online: http://kostat.go.kr/portal/korea/kor_nw/2/1/index.board?bmode=read&bSeq=&aSeq=363362&pageNo=1&rowNum=10&navCount=10&currPg=&sTarget=title&sTxt= (accessed on 16 January 2020).

- Shinailbo. Recruitment of Senior Dreaming Traveler Course Students. Available online: http://www.shinailbo.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=1203658 (accessed on 16 January 2020).

- Hwang, J.; Han, H. Examining strategies for maximizing and utilizing brand prestige in the luxury cruise industry. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 244–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitsamer, B.F.; Brunner-Sperdin, A. Tourist destination perception and well-being: What makes a destination attractive? J. Vacat. Mark. 2017, 23, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.H.; Cai, L.A.; Wong, K.K. A model of senior tourism motivations—Anecdotes from Beijing and Shanghai. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1262–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milman, A. The impact of tourism and travel experience on senior travelers’ psychological well-being. J. Travel Res. 1998, 37, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Hsu, C.H.; Chan, A. Tour guide performance and tourist satisfaction: A study of the package tours in Shanghai. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2010, 34, 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, A.H.; Wong, K.K.; Chang, R.C. Critical issues affecting the service quality and professionalism of the tour guides in Hong Kong and Macau. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1442–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.-C. Examining the effect of tour guide performance, tourist trust, tourist satisfaction, and flow experience on tourists’ shopping behavior. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 19, 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaur, S.-H.; Teng, H.-Y. Exploring tour guiding styles: The perspective of tour leader roles. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.M. Tour guides and destination image: Evidence from Portugal. J. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 3, 129–150. [Google Scholar]

- Grzeskowiak, S.; Sirgy, M.J. Consumer well-being (CWB): The effects of self-image congruence, brand-community belongingness, brand loyalty, and consumption recency. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2007, 2, 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, J.J.; Asif, M. The Antecedents and Consequences of Travelers’ Well-Being Perceptions: Focusing on Chinese Tourist Shopping at a Duty Free. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 5081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.-H. Effects of cuisine experience, psychological well-being, and self-health perception on the revisit intention of hot springs tourists. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2014, 38, 243–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Swanson, S.R.; Chen, X. The impact of perceived service fairness and quality on the behavioral intentions of chinese hotel guests: The mediating role of consumption emotions. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Mi Jeon, S.; Sean Hyun, S. Chain restaurant patrons’ well-being perception and dining intentions: The moderating role of involvement. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 24, 402–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.-J.; Kim, I.; Hyun, S.S. Critical in-flight and ground-service factors influencing brand prestige and relationships between brand prestige, well-being perceptions, and brand loyalty: First-class passengers. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 32, S114–S138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lyu, S.O. The antecedents and consequences of well-being perception: An application of the experience economy to golf tournament tourists. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Han, H. A model of brand prestige formation in the casino industry. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 1106–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Han, H.; Choo, S.-W. A strategy for the development of the private country club: Focusing on brand prestige. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 1927–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perreault, W.D.; McCarthy, E.J. Manual of Objective Tests to Accompany Basic Marketing: A Global-Managerial Approach; McGraw-Hill Education, Europe: Irwin, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Steenkamp, J.-B.E.; Batra, R.; Alden, D.L. How perceived brand globalness creates brand value. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2003, 34, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, B.; Czellar, S. Prestige Brands or Luxury Brands? An Exploratory Inquiry on Consumer Perceptions. In Marketing in a Changing World: Scope, Opportunities and Challenges, Proceedings of the 31st EMAC Conference, Braga, Portugal, 28–31 May 2002; University of Minho: Braga, Portugal, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, N.; Line, N.D.; Merkebu, J. The impact of brand prestige on trust, perceived risk, satisfaction, and loyalty in upscale restaurants. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2016, 25, 523–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Hyun, S.S. The antecedents and consequences of brand prestige in luxury restaurants. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 17, 656–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Chernatony, L.; Dall’Olmo Riley, F. Defining a “brand”: Beyond the literature with experts’ interpretations. J. Mark. Manag. 1998, 14, 417–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, K.E.; Spangenberg, E.R.; Grohmann, B. Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian dimensions of consumer attitude. J. Mark. Res. 2003, 40, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Corfman, K.P. Quality and value in the consumption experience: Phaedrus rides again. Perceived Qual. 1985, 31, 31–57. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.; Ok, C. The antecedents and consequence of consumer attitudes toward restaurant brands: A comparative study between casual and fine dining restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 32, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J.J., Jr.; Brady, M.K.; Hult, G.T.M. Assessing the effects of quality, value, and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. J. Retail. 2000, 76, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, R.N.; Drew, J.H. A multistage model of customers’ assessments of service quality and value. J. Consum. Res. 1991, 17, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souiden, N.; Chtourou, S.; Korai, B. Consumer attitudes toward online advertising: The moderating role of personality. J. Promot. Manag. 2017, 23, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, M.M.; Ho, S.-C.; Liang, T.-P. Consumer attitudes toward mobile advertising: An empirical study. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2004, 8, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizman, A.; Yinon, Y. Engaging in distancing tactics among sport fans: Effects on self-esteem and emotional responses. J. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 142, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grzeskowiak, S.; Sirgy, M.J.; Lee, D.-J.; Claiborne, C. Housing well-being: Developing and validating a measure. Soc. Indic. Res. 2006, 79, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Lee, D.-J. Developing a measure of consumer well being in relation to personal transportation. Yonsei Bus. Rev. 2003, 40, 73–101. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.; Hyun, S.S. First-class airline travellers’ perception of luxury goods and its effect on loyalty formation. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 497–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westbrook, R.A. Product/consumption-based affective responses and postpurchase processes. J. Mark. Res. 1987, 24, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. Role of motivations for luxury cruise traveling, satisfaction, and involvement in building traveler loyalty. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 70, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lyu, S.O. Understanding first-class passengers’ luxury value perceptions in the US airline industry. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 28, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herr, P.M.; Kardes, F.R.; Kim, J. Effects of word-of-mouth and product-attribute information on persuasion: An accessibility-diagnosticity perspective. J. Consum. Res. 1991, 17, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderlund, M. Customer satisfaction and its consequences on customer behaviour revisited: The impact of different levels of satisfaction on word-of-mouth, feedback to the supplier and loyalty. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 1998, 9, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- East, R.; Hammond, K.; Wright, M. The relative incidence of positive and negative word of mouth: A multi-category study. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2007, 24, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.; Zhou, L. Consumers’ Motivations for Consumption of Foreign Products: An Empirical Test in the People’s Republic of China. Available online: http://www.u21global.edu.sg/PartnerAdmin/ViewContent?module=DOCUMENTLIBRARY&oid=14097 (accessed on 16 January 2020).

- Spector, P.E.; Fox, S. An emotion-centered model of voluntary work behavior: Some parallels between counterproductive work behavior and organizational citizenship behavior. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2002, 12, 269–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. Drivers of customer decision to visit an environmentally responsible museum: Merging the theory of planned behavior and norm activation theory. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 1155–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yu, J.; Kim, W. Youth travelers and waste reduction behaviors while traveling to tourist destinations. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 1119–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trang, H.L.T.; Lee, J.-S.; Han, H. How do green attributes elicit pro-environmental behaviors in guests? The case of green hotels in Vietnam. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. The tourist guide: The origins, structure and dynamics of a role. Ann. Tour. Res. 1985, 12, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heung, V.C. Effects of tour leader’s service quality on agency’s reputation and customers’ word-of-mouth. J. Vacat. Mark. 2008, 14, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, R.; Ham, S. Improving the quality of tour guiding: Towards a model for tour guide certification. J. Ecotourism 2005, 4, 178–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowie, D.; Chang, J.C. Tourist satisfaction: A view from a mixed international guided package tour. J. Vacat. Mark. 2005, 11, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwel, S.; Lingqiang, Z.; Asif, M.; Hwang, J.; Hussain, A.; Jameel, A. The Influence of Destination Image on Tourist Loyalty and Intention to Visit: Testing a Multiple Mediation Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ap, J.; Wong, K.K. Case study on tour guiding: Professionalism, issues and problems. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, T.H.; Kim, J.; Yu, J.H. The differential roles of brand credibility and brand prestige in consumer brand choice. Psychol. Mark. 2010, 27, 662–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Kim, K.; Hwang, J. Self-Enhancement Driven First-Class Airline Travelers’ Behavior: The Moderating Role of Third-Party Certification. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.A.; Olson, J.C. Are product attribute beliefs the only mediator of advertising effects on brand attitude? J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Gwinner, K.P.; Gremler, D.D. Understanding relationship marketing outcomes: An integration of relational benefits and relationship quality. J. Serv. Res. 2002, 4, 230–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Choi, J.K. An investigation of passengers’ psychological benefits from green brands in an environmentally friendly airline context: The moderating role of gender. Sustainability 2018, 10, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.; Hsu, C.H.; Baum, T. The impact of tour service performance on tourist satisfaction and behavioral intentions: A study of Chinese tourists in Hong Kong. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 32, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.; Lin, V.S.; Hung, K. China’s generation Y’s expectation on outbound group package tour. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 19, 617–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.V.T.; Han, H.; Sahito, N.; Lam, T.N. The Bookstore-Café: Emergence of a New Lifestyle as a “Third Place” in Hangzhou, China. Space Cult. 2019, 22, 216–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, M.; Asif, M.; Hussain, A.; Jameel, A. Exploring the impact of ethical leadership on job satisfaction and organizational commitment in public sector organizations: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2019, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural equation modeling with AMOS, EQS, and LISREL: Comparative approaches to testing for the factorial validity of a measuring instrument. Int. J. Test. 2001, 1, 55–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Sahito, N.; Thi Nguyen, T.V.; Hwang, J.; Asif, M. Exploring the Features of Sustainable Urban Form and the Factors that Provoke Shoppers towards Shopping Malls. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Jameel, A.; Sahito, N.; Hwang, J.; Hussain, A.; Manzoor, F. Can Leadership Enhance Patient Satisfaction? Assessing the Role of Administrative and Medical Quality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Jameel, A.; Hussain, A.; Hwang, J.; Sahito, N. Linking Transformational Leadership with Nurse-Assessed Adverse Patient Outcomes and the Quality of Care: Assessing the Role of Job Satisfaction and Structural Empowerment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Asif, M.; Qing, M.; Hwang, J.; Shi, H. Ethical Leadership, Affective Commitment, Work Engagement, and Creativity: Testing a Multiple Mediation Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameel, A.; Asif, M.; Hussain, A. Good Governance and Public Trust: Assessing the Mediating Effect of E-Government in Pakistan. Lex Localis J. Local Self Gov. 2019, 17, 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Asif, M.; Jameel, A.; Hwang, J.; Sahito, N.; Kanwel, S. Promoting OPD Patient Satisfaction through Different Healthcare Determinants: A Study of Public Sector Hospitals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameel, A.; Asif, M.; Hussain, A.; Hwang, J.; Sahito, N.; Bukhari, M.H. Assessing the Moderating Effect of Corruption on the E-Government and Trust Relationship: An Evidence of an Emerging Economy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nation. United Nations World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/publications/world-population-prospects-2015-revision.html (accessed on 16 January 2020).

- Alén, E.; Domínguez, T.; Losada, N. New Opportunities for the Tourism Market: Senior Tourism and Accessible Tourism. Available online: https://books.google.com.hk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=acycDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA139&dq=+New+opportunities+for+the+tourism+market:+Senior+tourism+and+accessible+tourism.+&ots=dhYr8g6TqH&sig=7MquUrTflOMb3S_ET2maBuFiXzo&redir_esc=y&hl=zh-CN&sourceid=cndr#v=onepage&q=New%20opportunities%20for%20the%20tourism%20market%3A%20Senior%20tourism%20and%20accessible%20tourism.&f=false (accessed on 16 January 2020).

- Patterson, I.; Balderas, A. Continuing and Emerging Trends of Senior Tourism: A Review of the Literature. J. Popul. Ageing 2018, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sert, A.N. Senior Tourism in the Aging World. Available online: https://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/60915996/Theory_and_Practice_in_Social_Sciences20191016-93216-1sk6xu2.pdf?response-content-disposition=inline%3B%20filename%3DTheory_and_Practice_in_Social_Sciences.pdf&X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Credential=AKIAIWOWYYGZ2Y53UL3A%2F20200206%2Fus-east-1%2Fs3%2Faws4_request&X-Amz-Date=20200206T100622Z&X-Amz-Expires=3600&X-Amz-SignedHeaders=host&X-Amz-Signature=0bc6c7d1eb1b16ba0cf5af7255cf46ddde2f8cdf89e57521a357f1e8c6a75f07#page=497 (accessed on 16 January 2020).

- Nella, A.; Christou, E. Extending Tourism Marketing: Implications for Targeting the Senior Tourists’ Segment. J. Tour. Herit. Serv. Mark. 2016, 2, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Geva, A.; Goldman, A. Satisfaction measurement in guided tours. Ann. Tour. Res. 1991, 18, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | N | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Men | 95 | 29.2 |

| Women | 228 | 70.2 |

| Educational Level | ||

| High school diploma | 73 | 22.5 |

| Associate’s degree | 29 | 8.9 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 181 | 55.7 |

| Graduate degree | 42 | 12.9 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 4 | 1.2 |

| Married | 314 | 96.6 |

| Others (divorced and widow/widower) | 7 | 2.2 |

| Monthly income | ||

| Less than US$ 1000 | 8 | 2.5 |

| US$ 1001~US$ 2000 | 54 | 16.6 |

| US$ 2001~US$ 3000 | 58 | 17.8 |

| US$ 3001~US$ 4000 | 71 | 21.8 |

| US$ 4001~US$ 5000 | 59 | 18.2 |

| US$ 5001~US$ 6000 | 47 | 14.5 |

| More than US$ 6001 | 28 | 8.6 |

| Mean age = 69.20 years old |

| Construct and Scale Item | Standardized Loading a |

|---|---|

| Package tour prestige | |

| My package tour is prestigious. | 0.935 |

| My package tour has high status. | 0.940 |

| My package tour is very upscale. | 0.897 |

| Seniors’ WBP | |

| My package tour plays an important role in my well-being. | 0.925 |

| My package tour meets my overall well-being needs. | 0.938 |

| My package tour plays an important role in enhancing my QOL. | 0.918 |

| Consumer attitude | |

| Favorable—Unfavorable | 0.899 |

| Like—Dislike | 0.916 |

| Good—Bad | 0.918 |

| Pleasant—Unpleasant | 0.924 |

| Positive—Negative | 0.922 |

| WOM | |

| I will encourage others to use the travel agency. | 0.907 |

| I will spread the news about the good aspects of the travel agency to others. | 0.966 |

| I will recommend the travel agency to others. | 0.926 |

| Goodness-of-fit statistics: χ2 = 259.722, df = 71, p < 0.001, χ2/df = 3.658, NFI = 0.957, CFI = 0.968, IFI = 0.968, TLI = 0.959, RMSEA = 0.071 | |

| Variables | Mean (SD) | AVE | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Brand prestige | 4.30 (0.94) | 0.854 | 0.946 a | 0.716 b | 0.746 | 0.677 |

| (2) Seniors’ WBP | 4.37 (0.95) | 0.859 | 0.513c | 0.948 | 0.750 | 0.696 |

| (3) Consumer attitude | 4.52 (1.10) | 0.839 | 0.557 | 0.563 | 0.963 | 0.733 |

| (4) WOM | 4.40 (0.99) | 0.871 | 0.458 | 0.484 | 0.537 | 0.953 |

| Independent Variable | Dependent Variable | Beta | t-Value | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Brand prestige | → | Seniors’ WBP | 0.896 | 21.236 | Supported |

| H2: Brand prestige | → | Consumer attitude | 0.371 | 3.503 | Supported |

| H3: Brand prestige | → | WOM | 0.102 | 0.939 | Not supported |

| H4: Seniors’ WBP | → | Consumer attitude | 0.418 | 3.941 | Supported |

| H5: Seniors’ WBP | → | WOM | 0.255 | 2.351 | Supported |

| H6: Consumer attitude | → | WOM | 0.465 | 7.097 | Supported |

| H7a: The moderating of tour guide services in the relationship between brand prestige and seniors’ WBP | Supported | ||||

| H7b: The moderating of tour guide services in the relationship between brand prestige and consumer attitude | Not supported | ||||

| H7d: The moderating of tour guide services in the relationship between seniors’ WBP and consumer attitude | Not supported | ||||

| H7e: The moderating of tour guide services in the relationship between seniors’ WBP and WOM | Not supported | ||||

| H7f: The moderating of tour guide services in the relationship between consumer attitude and WOM | Supported | ||||

| Goodness-of-fit statistics: χ2 = 259.722, df = 71, p < 0.001, χ2/df = 3.658, NFI = 0.957, CFI = 0.968, IFI = 0.968, TLI = 0.959, RMSEA = 0.070 | |||||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hwang, J.; Kim, J.J.; Lee, J.S.-H.; Sahito, N. How to Form Wellbeing Perception and Its Outcomes in the Context of Elderly Tourism: Moderating Role of Tour Guide Services. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1029. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17031029

Hwang J, Kim JJ, Lee JS-H, Sahito N. How to Form Wellbeing Perception and Its Outcomes in the Context of Elderly Tourism: Moderating Role of Tour Guide Services. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(3):1029. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17031029

Chicago/Turabian StyleHwang, Jinsoo, Jinkyung Jenny Kim, Jenni Soo-Hee Lee, and Noman Sahito. 2020. "How to Form Wellbeing Perception and Its Outcomes in the Context of Elderly Tourism: Moderating Role of Tour Guide Services" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 3: 1029. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17031029

APA StyleHwang, J., Kim, J. J., Lee, J. S.-H., & Sahito, N. (2020). How to Form Wellbeing Perception and Its Outcomes in the Context of Elderly Tourism: Moderating Role of Tour Guide Services. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 1029. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17031029