Can Socioeconomic, Health, and Safety Data Explain the Spread of COVID-19 Outbreak on Brazilian Federative Units?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Foundations

3. Methodology

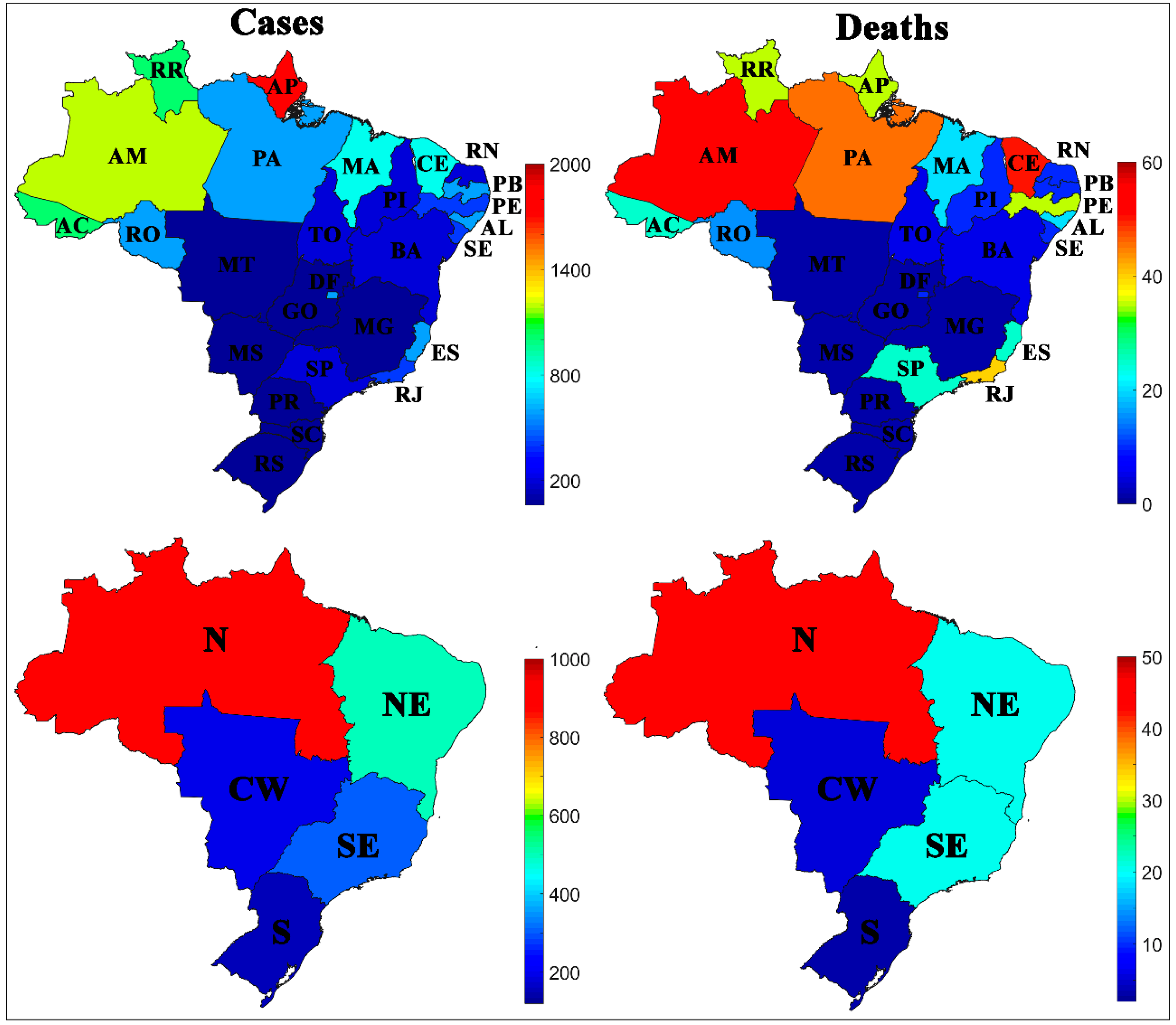

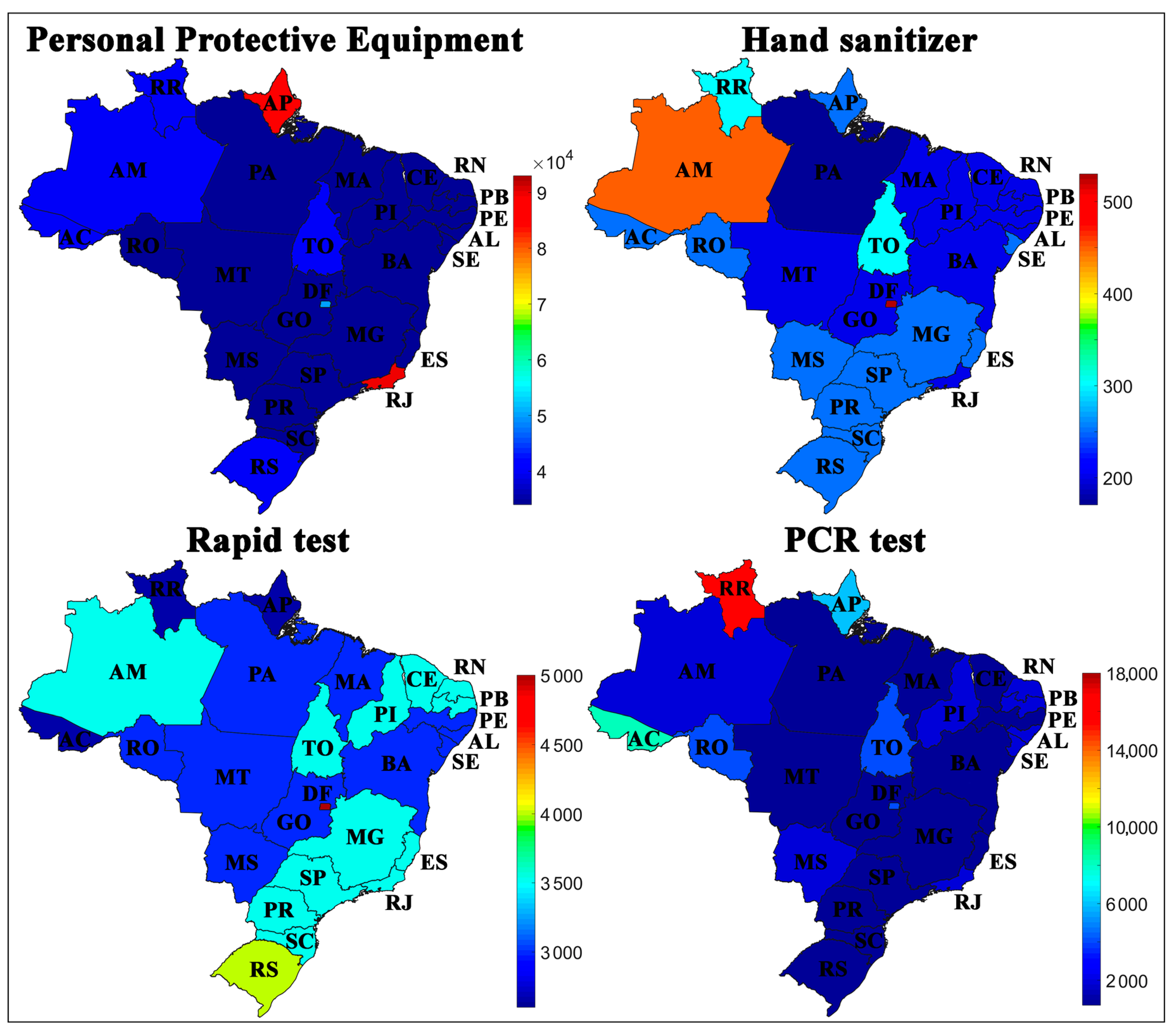

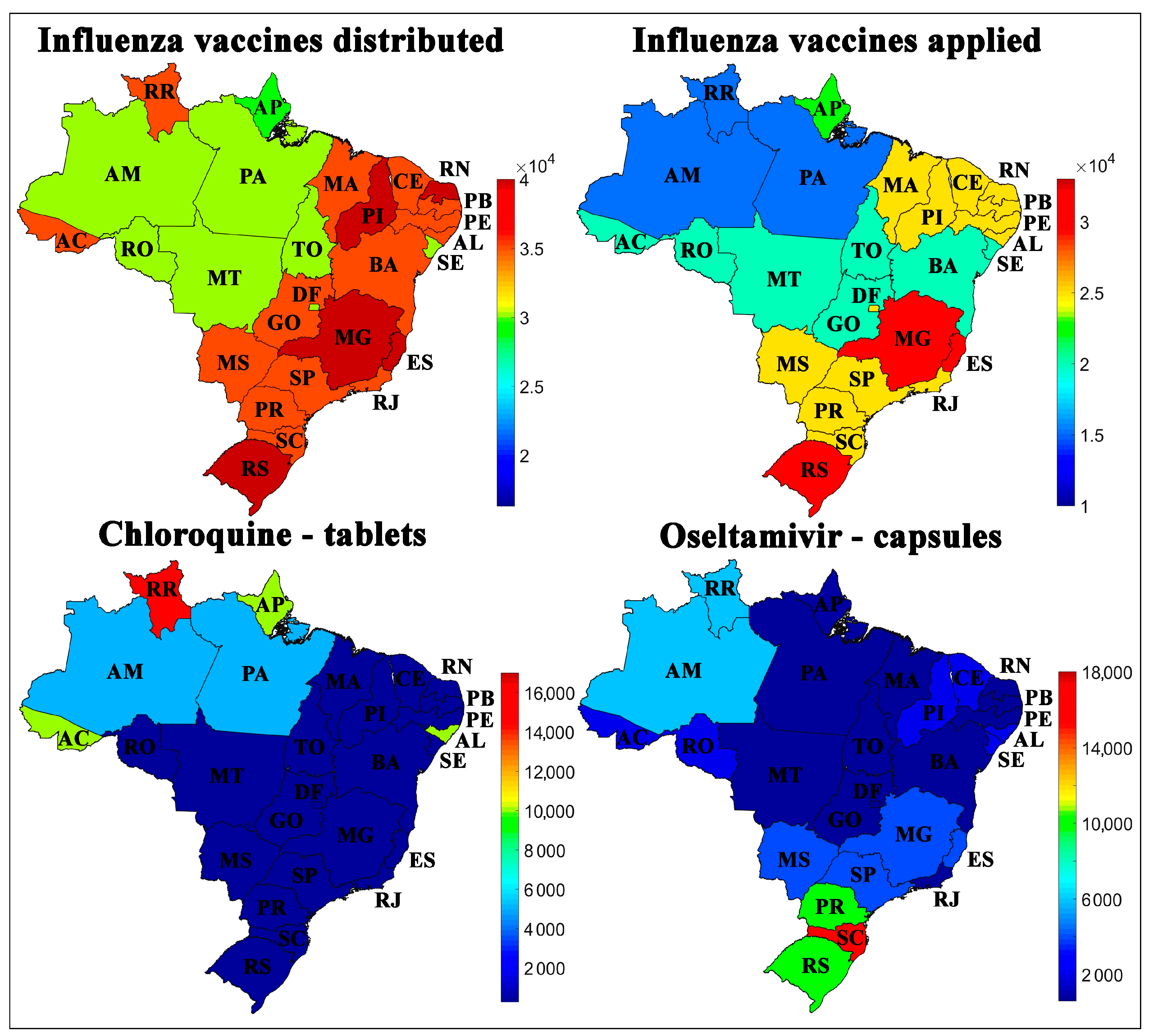

3.1. Dataset

3.2. Data Analysis by Artificial Neural Network

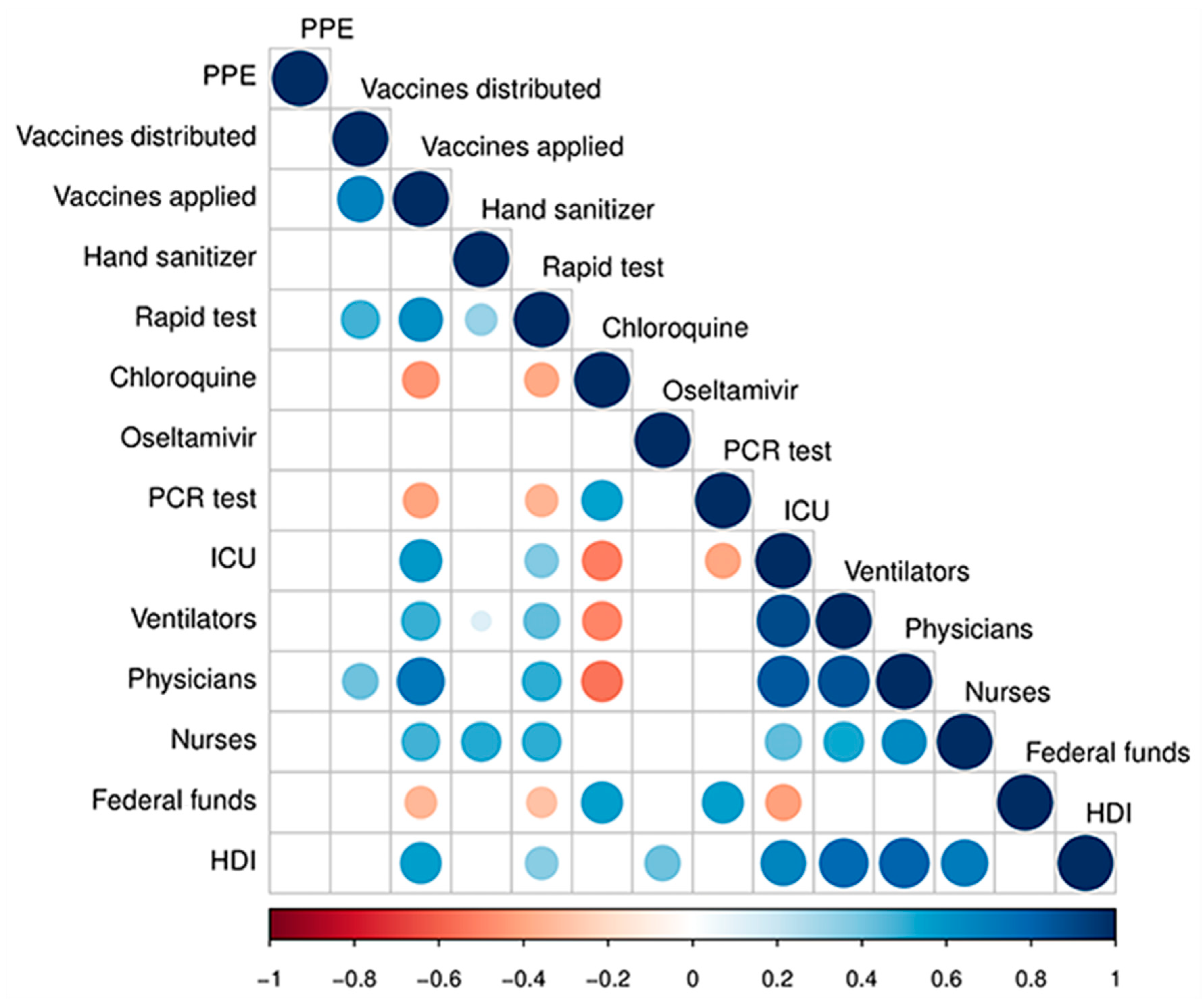

3.3. Spearman’s Correlation Test

4. Tests and Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wells:, C.R.; Sah, P.; Moghadas, S.M.; Pandey, A.; Shoukat, A.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Meyers, L.A.; Singer, B.H.; Galvani, A.P. Impact of international travel and border control measures on the global spread of the novel 2019 coronavirus outbreak. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 7504–7509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatto, M.; Bertuzzo, E.; Mari, L.; Miccoli, S.; Carraro, L.; Casagrandi, R.; Rinaldo, A. Spread and dynamics of the COVID-19 epidemic in Italy: Effects of emergency containment measures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 10484–10491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- Sanders, J.M.; Monogue, M.L.; Jodlowski, T.Z.; Cutrell, J.B. Pharmacologic Treatments for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Review. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020, 323, 1824–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AminJafari, A.; Ghasemi, S. The possible of immunotherapy for COVID-19: A systematic review. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Li, Y.; Zhang, A.L.; Wang, Y.; Molina, M.J. Identifying airborne transmission as the dominant route for the spread of COVID-19. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 14857–14863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Yan, C.; Fu, Q.; Xiao, K.; Yu, Y.; Han, D.; Wang, W.; Cheng, J. Possible environmental effects on the spread of COVID-19 in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosario, D.K.A.; Mutz, Y.S.; Bernardes, P.C.; Conte-Junior, C.A. Relationship between COVID-19 and weather: Case study in a tropical country. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2020, 113587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Fu, Y.; Jia, X.; Ding, S.; Wu, Y.; Huang, Z. Discovering Correlations between the COVID-19 Epidemic Spread and Climate. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Quteimat, O.M.; Amer, A.M. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Cancer Patients. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 43, 452–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, J.; Leelarathna, L.; Thabit, H. COVID-19: Impact of and on Diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2020, 11, 1429–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, C.; Gill, J.; Chun, D.; Babu, B.A. Deep learning system to screen coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia. Appl. Intell. 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho Rocha, W.F.; Do Prado, C.B.; Blonder, N. Comparison of chemometric problems in food analysis using non-linear methods. Molecules 2020, 25, 3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haykin, S. Neural Networks: A Comprehensive Foundation; Prentice Hall: New York, NY, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-0-02-352761-6. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, C.; Jiang, M.; Xu, Q.; Huang, X. Expectile regression neural network model with applications. Neurocomputing 2017, 247, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda-Miranda, A.; Castaño, V.M. Smart frost control in greenhouses by neural networks models. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2017, 137, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Taylor, J.W. Rule-based autoregressive moving average models for forecasting load on special days: A case study for France. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 266, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.M.; Huda, S.; Yearwood, J.; Jelinek, H.F.; Almogren, A. Multistage fusion approaches based on a generative model and multivariate exponentially weighted moving average for diagnosis of cardiovascular autonomic nerve dysfunction. Inf. Fusion 2018, 41, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, D.; Kourentzes, N.; Sandberg, R.; Niklewski, J. Automatic robust estimation for exponential smoothing: Perspectives from statistics and machine learning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 160, 113637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amo Baffour, A.; Feng, J.; Taylor, E.K. A hybrid artificial neural network-GJR modeling approach to forecasting currency exchange rate volatility. Neurocomputing 2019, 365, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda-Miranda, A.; Castaño-Meneses, V.M. Smart frost measurement for anti-disaster intelligent control in greenhouses via embedding IoT and hybrid AI methods. Meas. J. Int. Meas. Confed. 2020, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradeepkumar, D.; Ravi, V. Soft computing hybrids for FOREX rate prediction: A comprehensive review. Comput. Oper. Res. 2018, 99, 262–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda-Miranda, A.; Castaño-Meneses, V.M. Internet of things for smart farming and frost intelligent control in greenhouses. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 176, 105614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvan, D.; Cremasco, H.; Gomes Mantovani, A.C.; Bona, E.; Killner, M.; Borsato, D. Kinetic study of the transesterification reaction by artificial neural networks and parametric particle swarm optimization. Fuel 2020, 267, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S.; Sisson, S.A.; Sharma, A. Tools for enhancing the application of self-organizing maps in water resources research and engineering. Adv. Water Resour. 2020, 143, 103676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremasco, H.; Borsato, D.; Angilelli, K.G.; Galão, O.F.; Bona, E.; Valle, M.E. Application of self-organising maps towards segmentation of soybean samples by determination of inorganic compounds content. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, M.; Savada, F.Y.; Tashima, D.L.M.; Romagnoli, É.S.; Chendynski, L.T.; Silva, L.R.C.; Borsato, D. Application of the self-organizing map in the classification of natural antioxidants in commercial biodiesel. Biofuels 2018, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremasco, H.; Galvan, D.; Angilelli, K.G.; Borsato, D.; de Oliveira, A.G. Influence of film coefficient during multicomponent diffusion–KCL/NaCL in biosolid for static and agitated system using 3D computational simulation. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 39, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.R.C.; Angilelli, K.G.; Cremasco, H.; Romagnoli, É.S.; Galão, O.F.; Borsato, D.; Moraes, L.A.C.; Mandarino, J.M.G. Application of self-organising maps towards segmentation of soybean samples by determination of amino acids concentration. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 106, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, J.L.; Pereira, S.B.G.; Tanamati, A.; Tanamati, A.A.C.; Bona, E. Monitoring industrial hydrogenation of soybean oil using self-organizing maps. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2019, 31, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melin, P.; Monica, J.C.; Sanchez, D.; Castillo, O. Analysis of Spatial Spread Relationships of Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic in the World using Self Organizing Maps. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 138, 109917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebonye, N.M.; Eze, P.N.; Kingsley, J.; Gholizadeh, A.; Dajčl, J.; Drábek, O.; Němeček, K.; Borůvka, L. A combined self-organizing map artificial neural networks and conditional Gaussian simulation technique for mapping potentially toxic element hotspots in polluted mining soils. J. Geochem. Explor. 2020, 106680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadas, S.M.; Shoukat, A.; Fitzpatrick, M.C.; Wells, C.R.; Sah, P.; Pandey, A.; Sachs, J.D.; Wang, Z.; Meyers, L.A.; Singer, B.H.; et al. Projecting hospital utilization during the COVID-19 outbreaks in the United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 9122–9126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haghshenas, S.S.; Pirouz, B.; Haghshenas, S.S.; Pirouz, B.; Piro, P.; Na, K.S.; Cho, S.E.; Geem, Z.W. Prioritizing and analyzing the role of climate and urban parameters in the confirmed cases of COVID-19 based on artificial intelligence applications. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Anzi, B.S.; Alenizi, M.; Al Dallal, J.; Abookleesh, F.L.; Ullah, A. An overview of the world current and future assessment of novel COVID-19 trajectory, impact, and potential preventive strategies at healthcare settings. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eltoukhy, A.E.E.; Shaban, I.A.; Chan, F.T.S.; Abdel-Aal, M.A.M. Data analytics for predicting covid-19 cases in top affected countries: Observations and recommendations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IBGE. Estimated Brazilian Population for 2019. Available online: https://covid.saude.gov.br/ (accessed on 13 June 2020).

- MS Coronavirus Pandemic Data in Brazil. Available online: https://covid.saude.gov.br/ (accessed on 13 June 2020).

- Federal Government Federal Government of Brazil Transfers Financial Resources. Available online: https://covid-insumos.saude.gov.br/paineis/insumos/painel.php (accessed on 13 June 2020).

- Federal Government Covid-19 Spending Monitoring Panel. Available online: https://www.tesourotransparente.gov.br/visualizacao/painel-de-monitoramentos-dos-gastos-com-covid-19 (accessed on 13 June 2020).

- BCB Dollar Exchange Rate. Available online: https://www.bcb.gov.br/ (accessed on 13 June 2020).

- IBGE. Interactive Health Maps in Brazil. Available online: https://mapasinterativos.ibge.gov.br/covid/saude/ (accessed on 13 June 2020).

- ADHB. Brazilian Human Development Database. Available online: http://www.atlasbrasil.org.br/2013/pt/download/base/ (accessed on 13 June 2020).

- Taiyun, W.; Simko, V. R Package “Corrplot”: Visualization of a Correlation Matrix; CRAN, Germany; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ranney, M.L.; Griffeth, V.; Jha, A.K. Critical Supply Shortages—The Need for Ventilators and Personal Protective Equipment during the Covid-19 Pandemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, e41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, L.J.; Garner, L.V.; Smoot, J.W.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Saveson, C.J.; Sasso, J.M.; Gregg, A.C.; Soares, D.J.; Beskid, T.R.; et al. Assay Techniques and Test Development for COVID-19 Diagnosis. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6, 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, C.; Liu, G.; Luo, W.; Xia, N. Theranostics COVID-19: Progress in diagnostics, therapy and vaccination. Theranostics 2020, 10, 7821–7835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Wang, L.; Kuo, H.-C.D.; Shannar, A.; Peter, R.; Chou, P.J.; Li, S.; Hudlikar, R.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z.; et al. An Update on Current Therapeutic Drugs Treating COVID-19. Curr. Pharmacol. Rep. 2020, 6, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NDPH Low-Cost Dexamethasone Reduces Death by Up to One Third in Hospitalised Patients with Severe Respiratory Complications of COVID-19. Available online: https://www.recoverytrial.net/news/low-cost-dexamethasone-reduces-death-by-up-to-one-third-in-hospitalised-patients-with-severe-respiratory-complications-of-covid-19 (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- FDA Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Revokes Emergency Use Authorization for Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-revokes-emergency-use-authorization-chloroquine-and (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Li, I.W.; Hung, I.F.; To, K.K.; Chan, K.H.; Wong, S.S.Y.; Chan, J.F.; Cheng, V.C.; Tsang, O.T.; Lai, S.T.; Lau, Y.L.; et al. The natural viral load profile of patients with pandemic 2009 influenza A(H1N1) and the effect of oseltamivir treatment. Chest 2010, 137, 759–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Galvan, D.; Effting, L.; Cremasco, H.; Adam Conte-Junior, C. Can Socioeconomic, Health, and Safety Data Explain the Spread of COVID-19 Outbreak on Brazilian Federative Units? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8921. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238921

Galvan D, Effting L, Cremasco H, Adam Conte-Junior C. Can Socioeconomic, Health, and Safety Data Explain the Spread of COVID-19 Outbreak on Brazilian Federative Units? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(23):8921. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238921

Chicago/Turabian StyleGalvan, Diego, Luciane Effting, Hágata Cremasco, and Carlos Adam Conte-Junior. 2020. "Can Socioeconomic, Health, and Safety Data Explain the Spread of COVID-19 Outbreak on Brazilian Federative Units?" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 23: 8921. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238921

APA StyleGalvan, D., Effting, L., Cremasco, H., & Adam Conte-Junior, C. (2020). Can Socioeconomic, Health, and Safety Data Explain the Spread of COVID-19 Outbreak on Brazilian Federative Units? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(23), 8921. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238921