Change-of-Direction Performance in Elite Soccer Players: Preliminary Analysis According to Their Playing Positions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

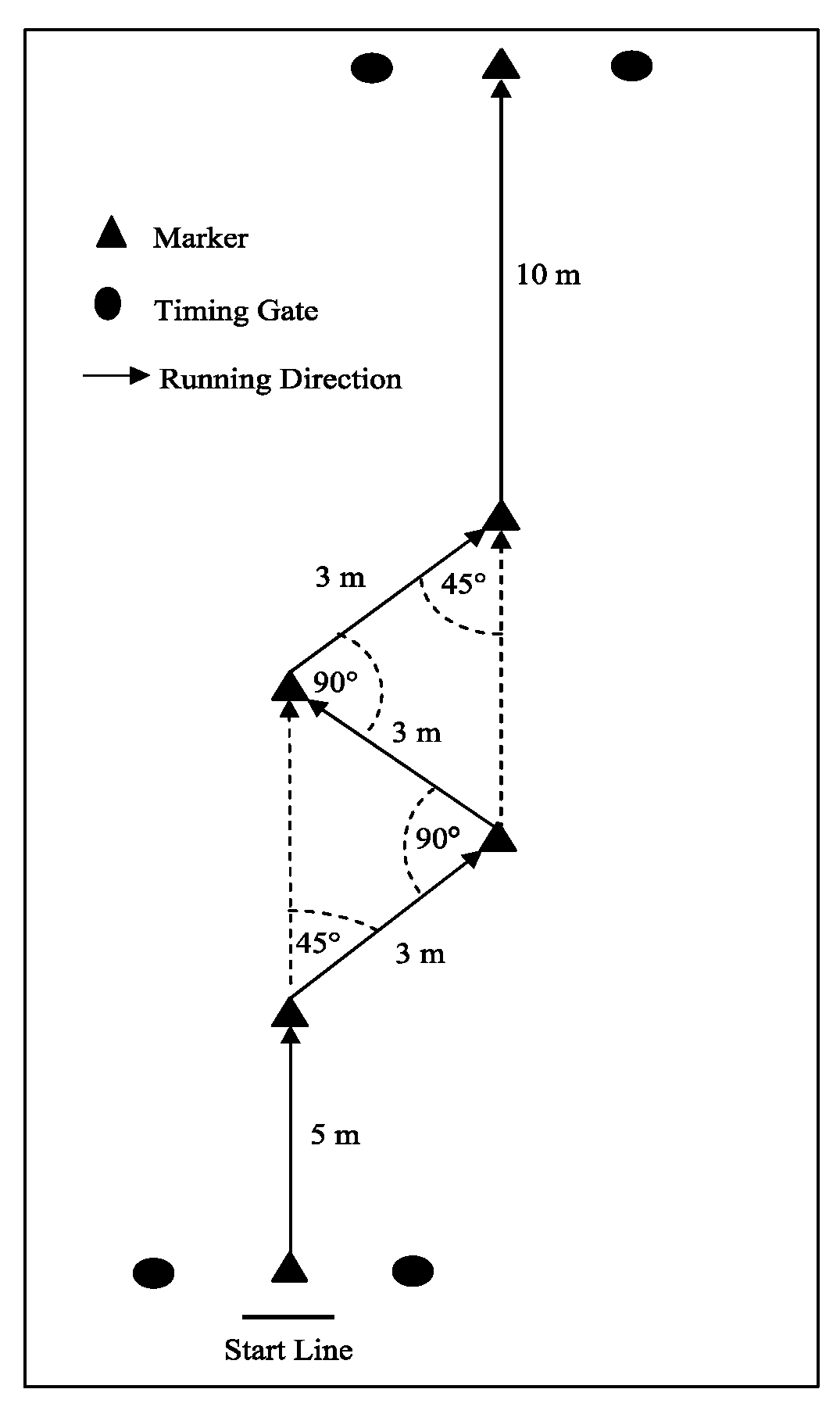

2.3. Change-of-Direction Tests

2.4. Linear Speed

2.5. Horizontal Jump

2.6. Dynamic Balance

2.7. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Reliability Analyses

3.2. Between-Group Differences in Measures of Change of Direction, Linear Speed, Dynamic Balance and Jump Performance

3.3. Correlations between Measures of Change of Direction with Jump Performance, Speed and Balance

3.4. Regression Analyses of Change-of-Direction and Linear Sprint, Dynamic Balance, and Jump Performance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dellal, A.; Chamari, K.; Wong, D.P.; Ahmaidi, S.; Keller, D.; Barros, R.; Carling, C. Comparison of physical and technical performance in European soccer match-play: FA Premier League and La Liga. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2011, 11, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carling, C. Analysis of physical activity profiles when running with the ball in a professional soccer team. J. Sports Sci. 2010, 28, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloomfield, J.; Polman, R.; O’Donoghue, P. Physical demands of different positions in FA Premier League soccer. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2007, 6, 63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gorostiaga, E.M.; Llodio, I.; Ibáñez, J.; Granados, C.; Navarro, I.; Ruesta, M.; Izquierdo, M. Differences in physical fitness among indoor and outdoor elite male soccer players. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2009, 106, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rampinini, E.; Impellizzeri, F.M.; Castagna, C.; Coutts, A.J.; Wisløff, U. Technical performance during soccer matches of the Italian Serie A league: Effect of fatigue and competitive level. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2009, 12, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapidžić, A.; Pojskić, H.; Muratović, M.; Užičanin, E.; Bilalić, J. Correlation of tests for evaluating explosive strength and agility of football players. Sport. Sci. Pract. Asp. 2011, 8, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Yanci, J.; Los Arcos, A.; Mendiguchia, J.; Brughelli, M. Relationships between sprinting, agility, one-and two-leg vertical and horizontal jump in soccer players. Kinesiology: Int. J. Fundam. Appl. Kinesiol. 2014, 46, 194–201. [Google Scholar]

- Goral, K. Examination of agility performances of soccer players according to their playing positions. Sport J. 2015, 51, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, J.M.; Young, W.B. CoD literature review: Classifications, training and testing. J. Sports Sci. 2006, 24, 919–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammami, R.; Granacher, U.; Pizzolato, F.; Chaouachi, M.; Chtara, M. Associations between Change of Direction, Balance, Speed, and Muscle Power in Prepubescent Soccer Players. J. Athl. Enhanc. 2017, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaouachi, A.; Manzi, V.; Chaalali, A.; Wong, D.P.; Chamari, K.; Castagna, C. Determinants analysis of change-of-direction ability in elite soccer players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2012, 26, 2667–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekulic, D.; Spasic, M.; Mirkov, D.; Cavar, M.; Sattler, T. Gender-specific influences of balance, speed, and power on agility performance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2013, 27, 802–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köklü, Y.; Alemdaroğlu, U.; Özkan, A.; Koz, M.; Ersöz, G. The relationship between sprint ability, agility and vertical jump performance in young soccer players. Sci. Sports 2015, 30, e1–e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sporiš, G.; Milanović, Z.; Trajković, N.; Joksimović, A. Correlation between speed, agility and quickness (SAQ) in elite young soccer players. Acta Kinesiol. 2011, 5, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Boone, J.; Vaeyens, R.; Steyaert, A.; Bossche, L.V.; Bourgois, J. Physical fitness of elite Belgian soccer players by player position. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2012, 26, 2051–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Salvo, V.; Baron, R.; Tschan, H.; Montero, F.C.; Bachl, N.; Pigozzi, F. Performance characteristics according to playing position in elite soccer. Int. J. Sports Med. 2007, 28, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Womersley, J.; Durnin, J.V.G.A. A comparison of the skinfold method with extent of ‘overweight’and various weight-height relationships in the assessment of obesity. Br. J. Nutr. 1977, 38, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockie, R.G.; Schultz, A.B.; Callaghan, S.J.; Jeffriess, M.D.; Berry, S.P. Reliability and validity of a new test of change-of-direction speed for field-based sports: The change-of-direction and acceleration test (CODAT). J. Sports Sci. Med. 2013, 12, 88. [Google Scholar]

- Hammami, R.; Sekulic, D.; Selmi, M.A.; Fadhloun, M.; Spasic, M.; Uljevic, O.; Chaouachi, A. Maturity status as a determinant of the relationships between conditioning qualities and preplanned agility in young handball athletes. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2018, 32, 2302–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockie, R.G.; Schultz, A.B.; Callaghan, S.J.; Jeffriess, M.D. The effects of traditional and enforced stopping speed and agility training on multidirectional speed and athletic function. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2014, 28, 1538–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamari, K.; Chaouachi, A.; Hambli, M.; Kaouech, F.; Wisløff, U.; Castagna, C. The five-jump test for distance as a field test to assess lower limb explosive power in soccer players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2008, 22, 944–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fusco, A.; Giancotti, G.F.; Fuchs, P.X.; Wagner, H.; da Silva, R.A.; Cortis, C. Y balance test: Are we doing it right? J. Sci. Med. Sport 2020, 23, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, W.G. Competitive performance of elite track-and-field athletes: Variability and smallest worthwhile enhancements. Sports Sci. 2005, 9, 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psys. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D.A. Statistics for the Social and Behavioral Sciences; Little Brown: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, C.G.; Kim, R.S.; Aloe, A.M.; Becker, B.J. Extracting the Variance Inflation Factor and Other Multicollinearity Diagnostics from Typical Regression Results. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 39, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, P. The Handbook Psychological Testing, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, H. An index of factor simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, R.S.; Read, P.; Oliver, J.L.; Meyers, R.W.; Nimphius, S.; Jeffreys, I. Considerations for the development of agility during childhood and adolescence. Strength Cond. J. 2013, 35, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahim, M.B.; Bougatfa, R.; Mohamed, A. Anthropometric and physical characteristics of Tunisians young soccer players. Adv. Phys. Educ. 2013, 3, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, S.M.; Gil, J.; Ruiz, F.; Irazusta, A.; Irazusta, J. Physiological and anthropometric characteristics of young soccer players according to their playing position: Relevance for the selection process. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2007, 21, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P. Total Soccer Fitness; RIO Network LLC.: Del Rio, TX, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mirkov, D.; Nedeljkovic, A.; Kukolj, M.; Ugarkovic, D.; Jaric, S. Evaluation of the reliability of soccer-specific field tests. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2008, 22, 1046–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karacabey, K. Sport performance and agility tests. J. Hum. Sci. 2013, 10, 1693–1704. [Google Scholar]

| Midfielders (n = 12) | Defenders (n = 14) | Strikers (n = 14) | Total (n = 40) | F | Sig. p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 25.28 ± 6.17 | 31.83 ± 19.15 | 25.80 ± 3.23 | 27.76 ± 11.77 | 0.62 | 0.55 |

| Height (cm) | 181.50 ± 6.44 | 170.00 ± 39.21 | 178.57 ± 5.09 | 176.45 ± 23.02 | 0.42 | 0.66 |

| SH (cm) | 89.50 ± 6.57 | 89.08 ± 13.08 | 89.00 ± 4.47 | 89.18 ± 8.47 | 0.00 | 0.99 |

| LL (cm) | 92.00 ± 7.87 | 85.42 ± 14.80 | 89.57 ± 4.43 | 88.85 ± 9.97 | 0.71 | 0.51 |

| BM (kg) | 77.60 ± 6.16 | 76.91 ± 18.71 | 75.07 ± 5.70 | 76.47 ± 11.49 | 0.08 | 0.93 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.56 ± 1.50 | 30.11 ± 18.86 | 23.51 ± 1.04 | 25.83 ± 11.12 | 0.78 | 0.48 |

| BF (%) | 11.38 ± 2.83 | 12.16 ± 3.40 | 10.97 ± 2.34 | 11.51 ± 2.79 | 0.30 | 0.74 |

| Criterion Measures | ICC3.1 (95% CI) | SEM | CV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CODATwb (s) | 0.92 (0.75–0.97) | 0.04 | 2.75 |

| CODATb (s) | 0.88 (0.71–0.95) | 0.06 | 2.86 |

| Sprint 5-m (s) | 0.94 (0.85–0.97) | 0.01 | 2.08 |

| Sprint 20-m (s) | 0.95 (0.88–0.98) | 0.01 | 1.14 |

| 5JT (m) | 0.91 (0.77–0.97) | 0.10 | 2.44 |

| CS-YBT (%) | 0.91 (0.78–0.96) | 0.49 | 2.40 |

| Midfielders (n = 12) | Defenders (n = 14) | Strikers (n = 14) | Total (n = 40) | F | Sig. p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CODATwb (s) | 5.28 ± 0.28 | 5.13 ± 0.18 | 5.09 ± 0.40 | 5.16 ± 0.29 | 0.71 | 0.50 |

| CODATb (s) | 6.73 ± 0.63 | 6.75 ± 0.24 | 6.27 ± 0.35 | 6.57 ± 0.46 | 2.78 | 0.09 |

| Sprint 5 (m) | 0.87 ± 0.03 | 0.84 ± 0.06 | 0.81±0.04 | 0.84 ± 0.05 | 2.69 | 0.09 |

| Sprint 20 (m) | 2.84 ± 0.09 | 2.75 ± 0.10 | 2.67 ± 0.08 | 2.75 ± 0.11 | 5.26 | 0.02 |

| 5JT (m) | 12.46 ± 1.07 | 12.85 ± 0.86 | 12.96 ± 0.57 | 12.77 ± 0.83 | 0.61 | 0.56 |

| CS-YBT (%) | 92.03 ± 6.90 | 95.01 ± 5.89 | 101.65 ± 7.72 | 96.44 ± 7.70 | 3.39 | 0.06 |

| WHOLE SAMPLE (n = 40) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Sprint (s) | Jump | Dynamic Balance | |||||||

| 5 (m) | 20 (m) | 5 JT (m) | CS YBT (%) | |||||||

| r-Value (r2) | rz-Value | r-Value (r2) | rz-Value | r-Value (r2) | rz-Value | r-Value (r2) | rz-Value | Mean rz-Value | Mean rz-Value (r2) | |

| CODATwb | 0.72 ** (0.52) | 0.91 | 0.54 * (0.29) | 0.60 | −0.62 ** (0.38) | 0.73 | −0.50 ** (0.25) | 0.55 | 0.698 | 0.595 (35) |

| CODATb | 0.52 ** (0.27) | 0.58 | 0.45 * (0.21) | 20 (m) | −0.64 ** (0.42) | 0.76 | −0.83 ** (0.68) | 0.753 | 0.610 (37) | |

| Mean rz-value † | N/A | 0.74 | N/A | 0.54 | N/A | 0.74 | N/A | 0.87 | 0.723 | 0.605 |

| Mean r-value (r2) † | N/A | 0.62 (38) | N/A | 0.50 (25) | N/A | 0.63 (40) | N/A | 0.67 (44) | - | - |

| DEFENDERS (n = 14) | ||||||||||

| Variables | Sprint (s) | Jump | Dynamic Balance | |||||||

| 5 (m) | 20 (m) | 5 JT (m) | CS YBT (%) | |||||||

| r-Value (r2) | rz-Value | r-Value (r2) | rz-Value | r-Value (r2) | rz-Value | r-Value (r2) | rz-Value | Mean rz-Value | Mean rz-Value (r2) | |

| CODATwb | 0.83 ** (0.69) | 1.19 | 0.96 ** (0.92) | 1.95 | −0.57 * (0.32) | 0.65 | −0.83 ** (0.68) | 1.19 | 1.245 | 0.798 (64) |

| CODATb | 0.78 ** (0.60) | 1.05 | 0.40 (0.16) | 0.42 | −0.76 ** (0.58) | 0.99 | −0.85 ** (0.73) | 1.26 | 0.930 | 0.698 (49) |

| Mean rz-value † | N/A | 1.12 | N/A | 1.18 | N/A | 0.82 | N/A | 1.22 | 1.085 | 0.775 (60) |

| Mean r-value (r2) † | N/A | 0.81 (65) | N/A | 0.68 (46) | N/A | 0.77 (44) | N/A | 0.84 (71) | - | - |

| MIDFIELDERS (n = 12) | ||||||||||

| Variables | Sprint (s) | Jump | Dynamic Balance | |||||||

| 5 (m) | 20 (m) | 5 JT (m) | CS YBT% | |||||||

| r-Value (r2) | rz-Value | r-Value (r2) | rz-Value | r-Value (r2) | rz-Value | r-Value (r2) | rz-Value | Mean rz-Value | Mean rz-Value (r2) | |

| CODATwb | 0.58 * (0.34) | 0.66 | 0.82 ** (0.68) | 1.16 | −0.58 * (0.34) | 0.66 | −0.62 * (0.39) | 0.73 | 0.803 | 0.650 (42) |

| CODATb | 0.68 * (0.46) | 0.83 | 0.73 * (0.53) | 0.93 | −0.67 * (0.44) | 0.81 | −0.89 * (0.79) | 1.42 | 0.998 | 0.743 (55) |

| Mean rz-value † | N/A | 0.74 | N/A | 1.04 | N/A | 0.73 | N/A | 1.07 | 0.895 | 0.708 (50) |

| Mean r-value (r2) † | N/A | 0.63 (40) | N/A | 0.78 (60) | N/A | 0.66 (43) | N/A | 0.76 (57) | - | - |

| STRIKERS (n = 14) | ||||||||||

| Variables | Sprint (s) | Jump | Dynamic Balance | |||||||

| 5 (m) | 20 (m) | 5 JT (m) | CS YBT% | |||||||

| r-Value | rz-Value | r-Value (r2) | rz-Value | r-Value (r2) | rz-Value | r-Value (r2) | rz-Value | Mean rz-Value | Mean rz-Value (r2) | |

| CODATwb | 0.86 ** (0.75) | 1.29 | 0.14 (0.02) | 0.14 | −0.84 ** (0.71) | 1.22 | −0.27 (0.007) | 0.28 | 0.733 | 0.528 (28) |

| CODATb | 0.12 (0.01) | 0.12 | 0.44 (0.19) | 0.47 | −0.75 ** (0.56) | 0.78 | −0.76 ** (0.58) | 1.00 | 0.593 | 0.518 (27) |

| Mean rz-value † | N/A | 0.70 | N/A | 0.30 | N/A | 1 | N/A | 0.64 | 0.660 | 0.525 (28) |

| Mean r-value (r2) † | N/A | 0.49 (24) | N/A | 0.29 (8) | N/A | 0.80 (63) | N/A | 0.52 (27) | - | - |

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Coefficients | t | Sig. | R Square (R2) (Adjusted R2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | ||||||

| CODATwb | 1 | (Constant) | 1.50 | 0.83 | 1.81 | 0.08 | ||

| Sprint 5-m | 4.36 | 0.99 | 0.72 | 4.42 | 0.000 | 0.52 (0.50) | ||

| CODATb | 1 | (Constant) | 11.38 | 0.77 | 14.73 | 0.000 | ||

| CS-YBT | −0.05 | 0.01 | −0.83 | −6.25 | 0.000 | 0.68 (0.66) | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sariati, D.; Hammami, R.; Chtara, M.; Zagatto, A.; Boullosa, D.; Clark, C.C.T.; Hackney, A.C.; Granacher, U.; Souissi, N.; Zouhal, H. Change-of-Direction Performance in Elite Soccer Players: Preliminary Analysis According to Their Playing Positions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8360. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228360

Sariati D, Hammami R, Chtara M, Zagatto A, Boullosa D, Clark CCT, Hackney AC, Granacher U, Souissi N, Zouhal H. Change-of-Direction Performance in Elite Soccer Players: Preliminary Analysis According to Their Playing Positions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(22):8360. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228360

Chicago/Turabian StyleSariati, Dorsaf, Raouf Hammami, Mokhtar Chtara, Alessandro Zagatto, Daniel Boullosa, Cain C. T. Clark, Anthony C. Hackney, Urs Granacher, Nizar Souissi, and Hassane Zouhal. 2020. "Change-of-Direction Performance in Elite Soccer Players: Preliminary Analysis According to Their Playing Positions" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 22: 8360. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228360

APA StyleSariati, D., Hammami, R., Chtara, M., Zagatto, A., Boullosa, D., Clark, C. C. T., Hackney, A. C., Granacher, U., Souissi, N., & Zouhal, H. (2020). Change-of-Direction Performance in Elite Soccer Players: Preliminary Analysis According to Their Playing Positions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8360. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228360