Relationship Between Prolonged Second Stage of Labor and Short-Term Neonatal Morbidity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

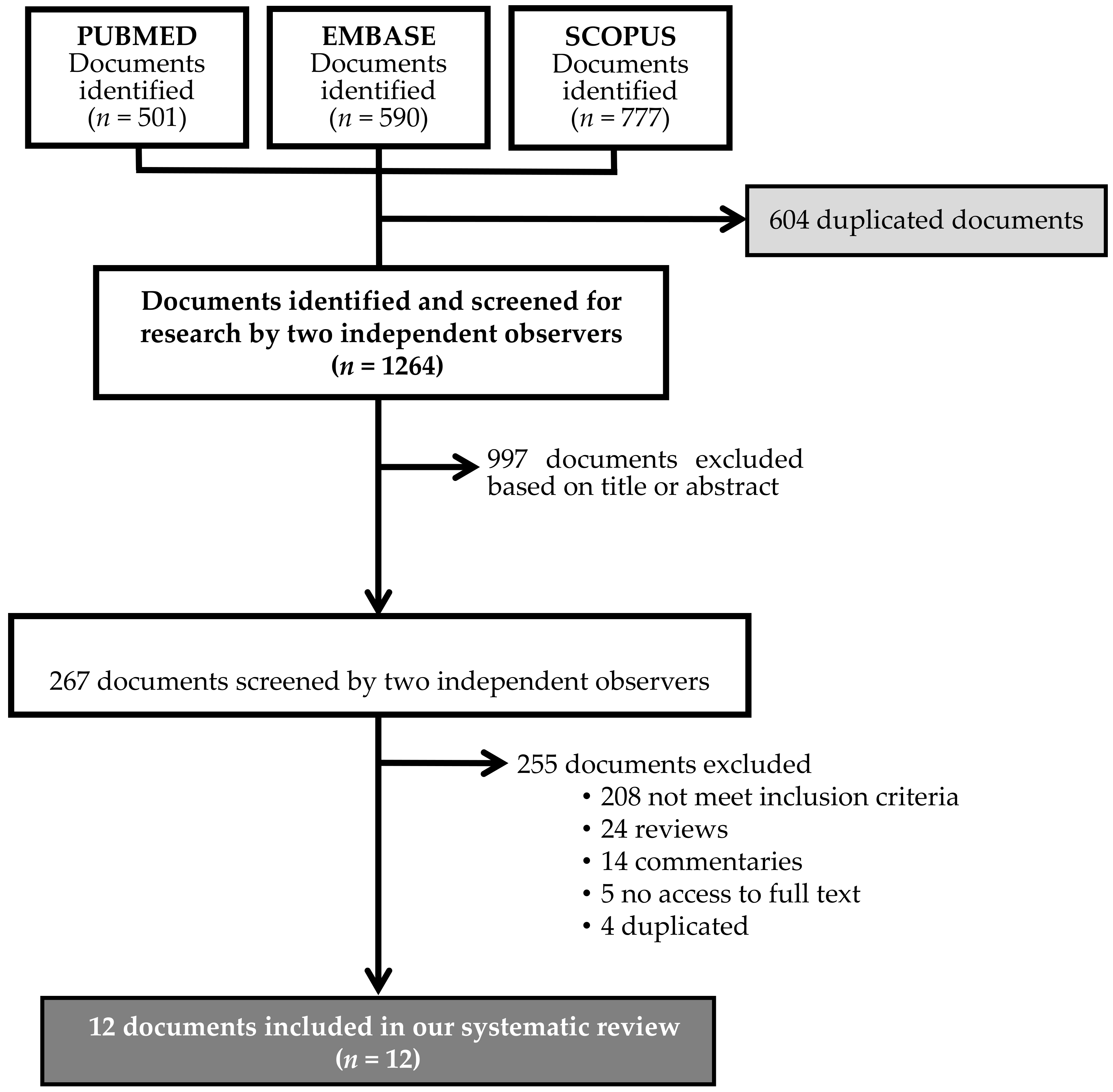

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Searches

2.2. Main Outcomes

2.3. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

2.4. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Study and Data Quality

3.4. Main Outcomes and Meta-Analysis

3.4.1. Nulliparous Women

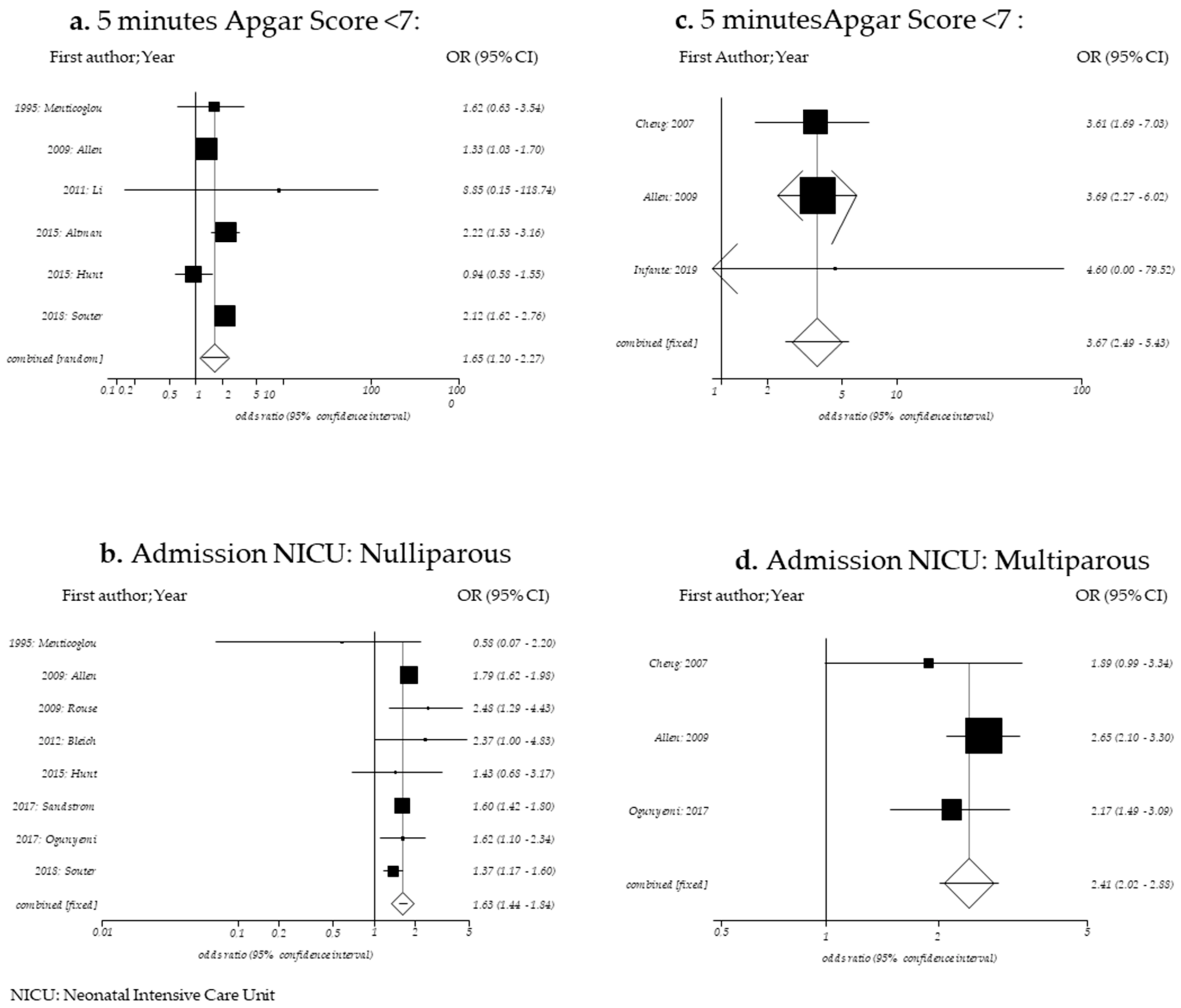

5 min Apgar score <7

Admission to Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

Neonatal Sepsis

Neonatal Death

Other Neonatal Outcomes

3.4.2. Multiparous Women

5 min Apgar Score < 7

Admission to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

Neonatal Sepsis

Neonatal Death

Other Neonatal Outcomes

3.4.3. Publication Bias

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Comparison with Existing Literature

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Search Strategies | ||

|---|---|---|

| Search Strategy | Database | Hits |

| “Labor Stage, Second” (Mesh) AND (length OR duration OR prolonged OR abnormal OR excessive) | PubMed | 501 |

| Scopus | 590 | |

| Embase | 777 | |

| Search Strategy “PICO” | ||

| Population | Nulliparous and Multiparous women | |

| Intervention | Second stage labor > 4 h in nulliparous Second stage labor > 3 h in multiparous | |

| Comparison | Second stage labor ≤ 4 h in nulliparous Second stage labor ≤ 3 h in multiparous | |

| Outcome | Neonatal morbidity: 5 min Apgar score < 7, admission to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, neonatal sepsis and neonatal death. | |

| . | 1995; Menticoglou | 2007; Cheng | 2009; Allen | 2009; Rouse | 2011; Li | 2012; Bleich | 2015; Altman | 2015; Hunt | 2017; Sandström | 2017; Ogunyemi | 2018; Souter | 2019; Infante |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Were the two groups similar and recruited from the same population? | Unclear * | No * | No * | Unclear * | Unclear * | Unclear * | Unclear * | Unclear * | Unclear * | Unclear * | Unclear * | Unclear * |

| 2. Were the exposures measured similarly to assign people to both exposed and unexposed groups? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 3. Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 4. Were confounding factors identified? | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 5. Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| 6. Were the groups/participants free of the outcome at the start of the study (or at the moment of exposure)? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 7. Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 8. Was the follow up time reported and sufficient to be long enough for outcomes to occur? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 9. Was follow up complete, and if not, were the reasons to loss to follow up described and explored? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 10. Were strategies to address incomplete follow up utilized? | NA | NA | Yes | NA | NA | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | NA | Yes |

| 11. Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes |

| 1 min Apgar Score <7 | 5 min Apgar Score <7 | 5 min Apgar Score <4 | 5 min Apgar Score ≤3 | Umbilical Artery pH <7 | Acidosis | Birth Depression | Resuscitation at Delivery | Intubation | Heart Compressions | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | ≤4 h | >4 h | ≤4 h | >4 h | ≤4 h | >4 h | ≤4 h | >4 h | ≤4 h | >4 h | ≤4 h | >4 h | ≤4 h | >4 h | ≤4 h | >4 h | ≤4 h | >4 h | ≤4 h | >4 h | |

| 1995; Menticoglou | NR | NR | 81/5733 | 7/308 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| 2009; Allen | NR | NR | 589/51,028 | 75/4908 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 862/51,028 | 138/4908 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| 2009; Rouse | NR | NR | NR | NR | 3/3983 | 0/143 | NR | NR | 15/3983 | 1/143 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 19/3983 | 1/143 | NR | NR | |

| 2011; Li | 17/295 | 8/12 | 3/295 | 1/12 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| 2012; Bleich | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 17/21,564 | 2/427 | 83/21,564 | 4/427 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 138/21,564 | 13/427 | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| 2015; Altman | NR | NR | 188/29,976 | 39/2820 | 32/29,976 | 8/2820 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| 2015; Hunt | NR | NR | 33/629 | 44/886 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| 2017; Sandström | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 330/30,453 | 31/2976 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 58/38,731 | 13/3808 | 36/38,731 | 10/3808 | |

| 2017; Ogunyemi | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| 2018; Souter | NR | NR | 200/16,682 | 84/3347 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 851/16,682 | 248/3347 | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Egger Bias (p-value) | 0.7861 | NC | 0.8132 | NC | NC | ||||||||||||||||

| I2 95% CI | 71.0 (2.1–85.6) | NC | NC | NC | NC | ||||||||||||||||

| Q Cochran (p-value) | 0.0041 | 0.7026 | 0.8132 | <0.001 | 0.681 | ||||||||||||||||

| OR 95% CI | 1.65 (1,20–2.27) * | 2.27 (1.08–4.74) * | 2.30 (0.94–5.69) | 2.60 (0.81–8.63) * | 2.19 (1.23–3.90) | ||||||||||||||||

| Meconium Aspiration | Meconium-Stained Amniotic Fluid | Admission to NICU | Neonatal Seizures | Sepsis | Birth Trauma | Minor Trauma | Major Trauma | Shoulder Dystocia | |||||||||||||

| Author | ≤4 h | >4 h | ≤4 h | >4 h | ≤4 h | >4 h | ≤4 h | >4 h | ≤4 h | >4 h | ≤4 h | >4 h | ≤4 h | >4 h | ≤4 h | >4 h | ≤4 h | >4 h | |||

| 1995; Menticoglou | NR | NR | NR | NR | 64/5733 | 2/308 | 5/5733 | 0/308 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||

| 2009; Allen | NR | NR | NR | NR | 3071/51,028 | 505/4908 | NR | NR | 195/51,028 | 30/4908 | NR | NR | 1311/51,028 | 162/4908 | 78/51,028 | 16/4908 | NR | NR | |||

| 2009; Rouse | NR | NR | NR | NR | 167/3983 | 14/143 | NR | NR | 6/3983 | 0/143 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||

| 2011; Li | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||

| 2012; Bleich | NR | NR | NR | NR | 172/21,564 | 8/427 | 41/21,564 | 13/427 | 39/21,564 | 0/427 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||

| 2015; Altman | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||

| 2015; Hunt | NR | NR | NR | NR | 12/629 | 24/886 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||

| 2017; Sandström | 58/38,731 | 10/3808 | NR | NR | 2373/38,731 | 360/3808 | 78/38,731 | 17/3808 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||

| 2017; Ogunyemi | NR | NR | 309/4215 | 37/272 | 372/4201 | 37/272 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 33/3814 | 1/250 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||

| 2018; Souter | NR | NR | NR | NR | 817/16,682 | 221/3347 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 367/16,682 | 74/3347 | |||

| Egger Bias (p-value) | 0.8326 | NC | NC | ||||||||||||||||||

| I2 95% CI | 48.8 (0.0–75,4) | 92.3 (78.6–95,8) | 0.0 (0–72.9) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Q Cochran (p-value) | 0.0573 | <0.001 | 0.7962 | ||||||||||||||||||

| OR 95% CI | 1.63 (1.53–1.74) | 4.67 (0,78–27.78) * | 1.57 (1.07–2.29) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Brachial Plexus Injury | Erb’s Palsy | Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy | Hypothermia Treatment | Composite Neonatal Morbidity | Neonatal Death | ||||||||||||||||

| Author | ≤4 h | >4 h | ≤4 h | >4 h | ≤4 h | >4 h | ≤4 h | >4 h | ≤4 h | >4 h | ≤4 h | >4 h | |||||||||

| 1995; Menticoglou | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0/5733 | 0/308 | |||||||||

| 2009; Allen | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||||||||

| 2009; Rouse | 10/3983 | 1/143 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 98/3983 | 6/143 | NR | NR | |||||||||

| 2011; Li | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||||||||

| 2012; Bleich | NR | NR | 82/21,564 | 2/427 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 3/21,564 | 0/427 | |||||||||

| 2015; Altman | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||||||||

| 2015; Hunt | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||||||||

| 2017; Sandström | NR | NR | NR | NR | 75/38,731 | 22/3808 | 16/38,731 | 7/3808 | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||||||||

| 2017; Ogunyemi | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||||||||

| 2018; Souter | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||||||||

| Egger Bias (p-value) | NC | ||||||||||||||||||||

| I2 95% CI | NC | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Q Cochran (p-value) | NC | ||||||||||||||||||||

| OR 95% CI | 7.21 (0.37–139.71) * | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 min Apgar Score <7 | Umbilical Artery pH <7.0 | Umbilical Artery pH <7.10 | Umbilical Artery Base Excess>−12 | Birth Depression | Advanced Neonatal Resuscitation | Meconium Amniotic Fluid or Meconium Staining | NICU Admission | Prolonged Neonatal Stay | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | ≤3 h | >3 h | ≤3 h | >3 h | ≤3 h | >3 h | ≤3 h | >3 h | >3 h | ≤3 h | ≤3 h | >3 h | ≤3 h | >3 h | ≤3 h | >3 h | ≤3 h | >3 h |

| 2007; Cheng | 60/4901 | 11/257 | 17/4901 | 1/257 | NR | NR | 31/4901 | 3/257 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1061/4901 | 73/257 | 145/4901 | 14/257 | 445/4901 | 34/257 |

| 2009; Allen | 311/64,586 | 17/968 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 553/64,586 | 27/968 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 2409/64,586 | 90/968 | NR | NR |

| 2017; Ogunyemi | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 290/5759 | 12/276 | 410/5700 | 40/278 | NR | NR |

| 2019; Infante | 3/2081 | 0/64 | NR | NR | 37/1858 | 3/54 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 39/2081 | 3/64 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Egger Bias (p-value) | NC | NC | NC | |||||||||||||||

| I2 95% CI | 0% (0.0%–72.9%) | NC | 0% (0.0%–72.9%) | |||||||||||||||

| Q Cochran (p-value) | 0.987 | 0.121 | 0.417 | |||||||||||||||

| OR 95% CI | 3.67 (2.49–5.43) | 1.29 (1.01–1.66) | 2.41 (2.02–2.88) | |||||||||||||||

| Minor Trauma | Major Trauma | Shoulder Dystocia | Composite Neonatal Morbidity | Any Perinatal Morbidity | ||||||||||||||

| Author | >3 h | >3 h | ≤3 h | >3 h | ≤3 h | >3 h | ≤3 h | >3 h | ≤3 h | >3 h | ||||||||

| 2007; Cheng | NR | NR | NR | NR | 117/4901 | 10/257 | 361/4901 | 33/257 | NR | NR | ||||||||

| 2009; Allen | 586/64,586 | 27/968 | 104/64,586 | 2/968 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 3662/64,586 | 128/968 | ||||||||

| 2017; Ogunyemi | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||||||||

| 2019; Infante | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 70/2081 | 6/64 | NR | NR | ||||||||

| Egger Bias (p-value) | NC | |||||||||||||||||

| I2 95% CI | NC | |||||||||||||||||

| Q Cochran (p-value) | 0.330 | |||||||||||||||||

| OR 95% CI | 1.97 (1.39–2.80) | |||||||||||||||||

References

- WHO Recommendations: Intrapartum Care for a Positive Childbirth Experience. Available online: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/intrapartum-care-guidelines/en/ (accessed on 2 October 2020).

- Myles, T.D.; Santolaya, J. Maternal and neonatal outcomes in patients with a prolonged second stage of labor. In Obstet Gynecol. 2003, 102. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12850607 (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Cheng, Y.W.; Hopkins, L.M.; Caughey, A.B. How long is too long: Does a prolonged second stage of labor in nulliparous women affect maternal and neonatal outcomes? Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 191, 933–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, V.M.; Baskett, T.F.; O’Connell, C.M.; McKeen, D.; Allen, A.C. Maternal and Perinatal Outcomes With Increasing Duration of the Second Stage of Labor. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 113, 1248–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Kohli, U.A.; Vardhan, S. Management of prolonged second stage of labor. Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 7, 2527–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Ray, C.; Audibert, F.; Goffinet, F.; Fraser, W. When to stop pushing: Effects of duration of second-stage expulsion efforts on maternal and neonatal outcomes in nulliparous women with epidural analgesia. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 201, 361.e1-361.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Simpson, K.R.; James, D.C. Effects of Immediate Versus Delayed Pushing During Second-Stage Labor on Fetal Well-Being. Nurs. Res. 2005, 54, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thavarajah, H.; Flatley, C.; Kumar, S. The relationship between the five minute Apgar score, mode of birth and neonatal outcomes. J. Matern. Neonatal Med. 2017, 31, 1335–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moiety, F.; Azzam, A.Z. Fundal pressure during the second stage of labor in a tertiary obstetric center: A prospective analysis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2014, 40, 946–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dystocia and the augmentation of labor. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 1996, 53, 73–80. [CrossRef]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Obstetric Care Consensus No. 1. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 123, 693–711. [CrossRef]

- NICE. Intrapartum Care for Healthy Women and Babies—NICE Guidelines. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg190/resources/intrapartum-care-for-healthy-women-and-babies-pdf-35109866447557 (accessed on 2 October 2020).

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; A Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339, b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hernández-Martínez, A.; Arias-Arias, A.; Morandeira-Rivas, A.; Pascual-Pedreño, A.I.; Ortiz-Molina, E.J.; Rodríguez-Almagro, J. Oxytocin discontinuation after the active phase of induced labor: A systematic review. Women Birth 2019, 32, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed on 2 October 2020).

- Scopus. Elsevier. Available online: https://www.elsevier.com/es-es/solutions/scopus (accessed on 2 October 2020).

- Investigación Biomédica—Embase. Available online: https://www.elsevier.com/es-es/solutions/embase-biomedical-research (accessed on 2 October 2020).

- Menticoglou, S.M.; Manning, F.; Harman, C.; Morrison, I. Perinatal outcome in relation to second-stage duration. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1995, 173, 906–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.W.; Hopkins, L.M.; Laros, R.K.; Caughey, A.B. Duration of the second stage of labor in multiparous women: Maternal and neonatal outcomes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 196, 585.e1-585.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouse, D.J.; Weiner, S.J.; Bloom, S.L.; Varner, M.W.; Spong, C.Y.; Ramin, S.M.; Caritis, S.N.; Peaceman, A.M.; Sorokin, Y.; Sciscione, A.; et al. Second-stage labor duration in nulliparous women: Relationship to maternal and perinatal outcomes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 201, 357.e1-357.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bleich, A.T.; Alexander, J.M.; McIntire, D.D.; Leveno, K.J. An Analysis of Second-Stage Labor beyond 3 Hours in Nulliparous Women. Am. J. Perinatol. 2012, 29, 717–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandström, A.; Altman, M.; Cnattingius, S.; Johansson, S.; Ahlberg, M.; Stephansson, O. Durations of second stage of labor and pushing, and adverse neonatal outcomes: A population-based cohort study. J. Perinatol. 2016, 37, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Infante-Torres, N.; Alarcón, M.M.; Gómez-Salgado, J.; Almagro, J.J.R.; Rubio-Álvarez, A.; Martínez, A.H. Relationship between the Duration of the Second Stage of Labour and Neonatal Morbidity. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal for Use in JBI Systematic Reviews. Checklist for Cohort Studies. Available online: https://joannabriggs.org/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI_Critical_Appraisal-Checklist_for_Cohort_Studies2017_0.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2020).

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses [Internet]. Br. Med. J. 2003, 327, 557–560. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12958120/ (accessed on 2 October 2020). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Egger, M.; Smith, G.D. meta-analysis bias in location and selection of studies. BMJ 1998, 316, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J.C.; Menticoglou, S.M. Perinatal Outcome in 1515 Cases of Prolonged Second Stage of Labour in Nulliparous Women. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2015, 37, 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunyemi, D.; Friedman, P.; Jovanovski, A.; Shah, I.; Hage, N.; Whitten, A. 890: Maternal and neonatal outcomes by parity and second-stage labor duration. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 216, S508–S509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Souter, V.; Chien, A.J.; Kauffman, E.; Sitcov, K.; Caughey, A.B. 365: Outcomes associated with prolonged second stage of labor in nulliparas. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 218, S226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.-H.; Zhang, H.-Y.; Ling, Y.; Jin, S. Effect of prolonged second stage of labor on maternal and neonatal outcomes. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2011, 4, 409–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, M.; Sandström, A.; Petersson, G.; Frisell, T.; Cnattingius, S.; Stephansson, O. Prolonged second stage of labor is associated with low Apgar score. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2015, 30, 1209–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gimovsky, A.C.; Guarente, J.; Berghella, V. Prolonged Second Stage in Nulliparous with Epidurals. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2017, 72, 399–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, M.R.; Lydon-Rochelle, M.T. Prolonged Second Stage of Labor and Risk of Adverse Maternal and Perinatal Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Birth 2006, 33, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gimovsky, A.C.; Berghella, V. Randomized Controlled Trial of Prolonged Second Stage. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2016, 71, 385–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipori, Y.; Grunwald, O.; Ginsberg, Y.; Beloosesky, R.; Weiner, Z. The impact of extending the second stage of labor to prevent primary cesarean delivery on maternal and neonatal outcomes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 2019, 220, 191.e1-191.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Definitions | Authors | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995; Menticoglou [18] | 2007; Cheng [19] | 2009; Allen [4] | 2009; Rouse [20] | 2012; Bleich [21] | 2017; Sandström [22] | 2019; Infante [23] | |

| Acidosis | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | A pH value <7.05 and base excess <−12 in the umbilical artery. | NR |

| Birth depression | NR | NR | Delay in initiating and maintaining respirations after birth requiring resuscitation by mask or endotracheal tube for at least 3 min, a 5 min Apgar score of 3 or less, or neonatal seizures due to hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Intubation | NR | NR | NR | Intubation in delivery room. | NR | NR | NR |

| Heart compressions | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Resuscitation in delivery room with heart compressions and/or intubation. | NR |

| Advanced neonatal resuscitation | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Type III: Oxygen therapy with positive intermittent pressure. Type IV: Endotracheal intubation, Type V: Cardiac massage and/or using drugs |

| Admission to Neonatal Intensive Care Unit | Need for admission to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit for any reason at all or with a 5 min Apgar score < 7 or arterial cord pH < 7.20. | NR | Neonatal intensive care unit admission with duration of stay longer than 24 h. | Admission to a neonatal intensive care unit for >48 h. | NR | NR | NR |

| Prolonged neonatal stay | NR | Neonatal stay >2 d for vaginal delivery and >4 d for caesarean delivery. | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Neonatal seizures | NR | NR | NR | NR | Seizures in the first 24 h of life. | NR | NR |

| Sepsis | NR | NR | Positive blood culture, septicemia or systematic infection. | NR | Positive blood culture. | NR | NR |

| Minor trauma | NR | NR | One or more of the following neonatal traumas: linear skull fracture, other fractures (clavicle, ribs, numerus, or femur), facial palsy, or cephalohematoma. | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Major trauma | NR | NR | One or more of the following neonatal traumas: depressed skull fracture, intracranial hemorrhage, or brachial plexus palsy. | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Composite neonatal morbidity | NR | Composite variable for 5 min Apgar <7, UA pH <7.0, UA base excess ≥12, shoulder dystocia, NICU stay, and birth trauma (which includes brachial plexus injury, facial nerve palsy, clavicular fracture, skull fracture, head laceration, and cephalohematoma defined and diagnosed by the attending pediatrician). | Composite of any of the other neonatal outcomes. | Any of the following occurrences: a 5 min Apgar score <4, an umbilical artery pH <7.0, seizures, intubation, stillbirth, neonatal death, or admission to a NICU. | NR | NR | Composite of any of the other neonatal outcomes. |

| Neonatal death | Death during the second stage of labor or in the first 28 d of life | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| YEAR OF PUBLICATION AUTOR | COUNTRY | STUDY DESIGN | POPULATION UNDER STUDY | DURATION OF SECOND STAGE OF LABOUR n (%) | DELIVERY MODE N (%) | USE OF EA N (%) | INCLUSION/EXCLUSION CRITERIA | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–1 h | 1–2 h | 2–3 h | 3–4 h | >4 h | Spontaneous Vaginal Delivery | Operative Vaginal Delivery | Caesarean Section | |||||||

| NULLIPAROUS | 1995/ Menticoglou [18] | Canada | Cohort study | 6041 | 2622 (43.4) | 1805 (29.9) | 927 (15.3) | 379 (6.3) | 308 (5.1) | 4942 (81.8) | 932 (15.5) | 167 (2.7) | NR |

|

| 2009/ Rouse [20] | United States | Secondary analysis of a clinical trial | 4126 | 1901 (46.1) | 1251 (30.3) | 614 (14.9) | 217 (5.2) | 143 (3.5) | 3054 (74.0) | 765 (18.5) | 307 (7.5) | 3916 (95.0) |

| |

| 2011/ Li [31] | China | Case-control study | 307 | 206 (67.1) | 29 (9.4) | 60 (19.5) | 12 (4.0) | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| ||

| 2012/ Bleich [21] | United States | Cohort study | 21,991 | 13,736 (62.5) | 4933 (22.4) | 1833 (8.3) | 1062 (4.8) | 427 (2.0) | 19,326 (87.9) | 1367 (6.2) | 1298 (5.9) | 13,676 (62.2) |

| |

| 2015/ Altman [32] | Sweden | Cohort study | 32,796 | 10,731 (32.7) | 9491 (29.0) | 5856 (17.8) | 3898 (11.9) | 2820 (8.6) | NR | 6728 (20.5) | NR | 19,417 (59.2) |

| |

| 2015/ Hunt [28] | Canada | Cohort study | 1515 | NC | NC | NC | 629 (41.5) | 886 (58.5) | 615 (40.6) | 662 (43.7) | 238 (15.7) | NR |

| |

| 2017/ Sandström [22] | Sweden | Cohort study | 42,539 | 13,558 (31.9) | 12,225 (28.7) | 7710 (18.1) | 5238 (12.3) | 3808 (9.0) | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| |

| 2018/ Souter [30] | United States | Cohort study in a poster session | 20,029 | 16,682 (83.3) | 3347 (16.7) | 14,942 (74.6) | 3015 (15.0) | 2072 (10.4) | 20,029 (100) |

| ||||

| MULTIPAROUS | 2007/ Cheng [19] | United States | Cohort study | 5158 | 4112 (79.7) | 550 (10.7) | 239 (4.6) | 257 (5.0) | 4480 (86.8) | 414 (8.1) | 263 (5.1) | 2274 (44.1) |

| |

| 2019/ Infante [23] | Spain | Cohort study | 2145 | 1589 (74.1) | 327 (15.2) | 165 (7.7) | 64 (3.0) | 2070 (96.5) | 75 (3.5) | NR | 1675 (78.1) |

| ||

| NULLIPAROUS AND MULTIPAROUS | 2009/ Allen [4] | Canada | Cohort study | 55,936 nulliparous | 38,790 (69.3) | 7832 (14.0) | 4406 (7.9) | 4908 (8.8) | 101,897 (83.8) | 15,865 (13.1) | 3734 (3.1) | 61,077 (50.3) |

| |

| 65,554 multiparous | 59,227 (90.3) | 4171 (6.3) | 1188 (1.8) | 968 (1.6) | ||||||||||

| 2017/ Ogunyemi [29] | United States | Poster session | 10,487 * | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| |

| Variable | Number of Studies | Number of Subjects | Egger Bias (p-Value) | I2 95% CI | Cochran’s Q (p-Value) | OR 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 min Apgar Score <7 | 1 | 307 | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| 5 min Apgar score <7 | 6 | 116,624 | 0.7861 | 71.0 (2,1–85,6) | 0.0041 | 1.65 (1.20–2.27) |

| 5 min Apgar score <4 | 2 | 36,922 | NC | NC | 0.7026 | 2.27 (1.08–4.74) |

| 5 min Apgar Score <3 | 1 | 21,991 | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| Umbilical artery pH <7 | 2 | 29,117 | 0.8132 | NC | 0.8132 | 2.30 (0.94–5.69) |

| Umbilical artery pH <7.10 | 0 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Umbilical artery base excess >−12 | 0 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Acidosis | 1 | 33,429 | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| Birth depression | 1 | 55,936 | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| Resuscitation at delivery | 2 | 42,020 | NC | NC | <0.001 | 2.60 (0.81–8.63) |

| Intubation | 2 | 46,665 | NC | NC | 0.681 | 2.19 (1.23–3.90) |

| Heart compressions | 1 | 42,539 | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| ANR | 0 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Meconium aspiration | 1 | 42,539 | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| Meconium-stained amniotic fluid | 1 | 4487 | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| Admission to Neonatal Intensive Care Unit | 8 | 156,650 | 0.8326 | 48.8 (0.0–75.4) | 0.0573 | 1.63 (1.44–1.84) |

| Prolonged neonatal stay | 0 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Neonatal seizures | 3 | 70,571 | NC | 92.3 (78.6–95.8) | <0.001 | 4.67 (0.78–27.78) |

| Neonatal sepsis | 3 | 82,053 | NC | 0.0 (0–72.9) | 0.7962 | 1.57 (1.07–2.29) |

| Birth trauma | 1 | 4064 | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| Minor trauma | 1 | 55,936 | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| Major trauma | 1 | 55,936 | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| Shoulder dystocia | 1 | 20,029 | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| Brachial plexus injury | 1 | 4126 | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| Erb’s palsy | 1 | 21,991 | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy | 1 | 42,539 | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| Hypothermia treatment | 1 | 42,539 | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| Composite neonatal morbidity | 1 | 4126 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Any perinatal morbidity | 0 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Neonatal death | 2 | 28,032 | NC | NC | NC | 7.21 (0.37–139.71) |

| Variable | Number of Studies | Number of Subjects | Egger Bias (p-Value) | I2 95% CI | Cochran’s Q (p-Value) | OR 95% CI |

| 1 min Apgar Score < 7 | 0 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| 5 min Apgar score < 7 | 3 | 72,857 | NC | 0.0 (0.0–72.9) | 0.987 | 3.67 (2.48–5.43) |

| 5 min Apgar score < 4 | 0 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| 5 min Apgar Score ≤ 3 | 0 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Umbilical artery pH < 7 | 1 | 5158 | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| Umbilical artery pH < 7.10 | 1 | 1912 | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| Umbilical artery base excess > −12 | 1 | 5158 | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| Acidosis | 0 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Birth depression | 1 | 65,554 | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| Resuscitation at delivery | 0 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Intubation | 0 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Heart compressions | 0 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| ANR | 1 | 2145 | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| Meconium aspiration | 0 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Meconium-stained amniotic fluid | 2 | 11,193 | NC | NC | 0.121 | 1.29 (1.01–1.66) |

| Admission to Neonatal Intensive Care Unit | 3 | 76,692 | NC | 0.0 (0.0–72.9) | 0.417 | 2.41 (2.02–2.88) |

| Prolonged neonatal stay | 1 | 5158 | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| Neonatal seizures | 0 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Neonatal sepsis | 0 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Birth trauma | 0 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Minor trauma | 1 | 65,554 | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| Major trauma | 1 | 65,554 | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| Shoulder dystocia | 1 | 5158 | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| Brachial plexus injury | 0 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Erb’s palsy | 0 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy | 0 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Hypothermia treatment | 0 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Composite neonatal morbidity | 2 | 7303 | NC | NC | 0.330 | 1.97 (1.39–2.80) |

| Any perinatal morbidity | 1 | 65,554 | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| Neonatal death | 0 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Infante-Torres, N.; Molina-Alarcón, M.; Arias-Arias, A.; Rodríguez-Almagro, J.; Hernández-Martínez, A. Relationship Between Prolonged Second Stage of Labor and Short-Term Neonatal Morbidity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7762. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17217762

Infante-Torres N, Molina-Alarcón M, Arias-Arias A, Rodríguez-Almagro J, Hernández-Martínez A. Relationship Between Prolonged Second Stage of Labor and Short-Term Neonatal Morbidity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(21):7762. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17217762

Chicago/Turabian StyleInfante-Torres, Nuria, Milagros Molina-Alarcón, Angel Arias-Arias, Julián Rodríguez-Almagro, and Antonio Hernández-Martínez. 2020. "Relationship Between Prolonged Second Stage of Labor and Short-Term Neonatal Morbidity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 21: 7762. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17217762