Bleeding Bodies, Untrustworthy Bodies: A Social Constructionist Approach to Health and Wellbeing of Young People in Kenya

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

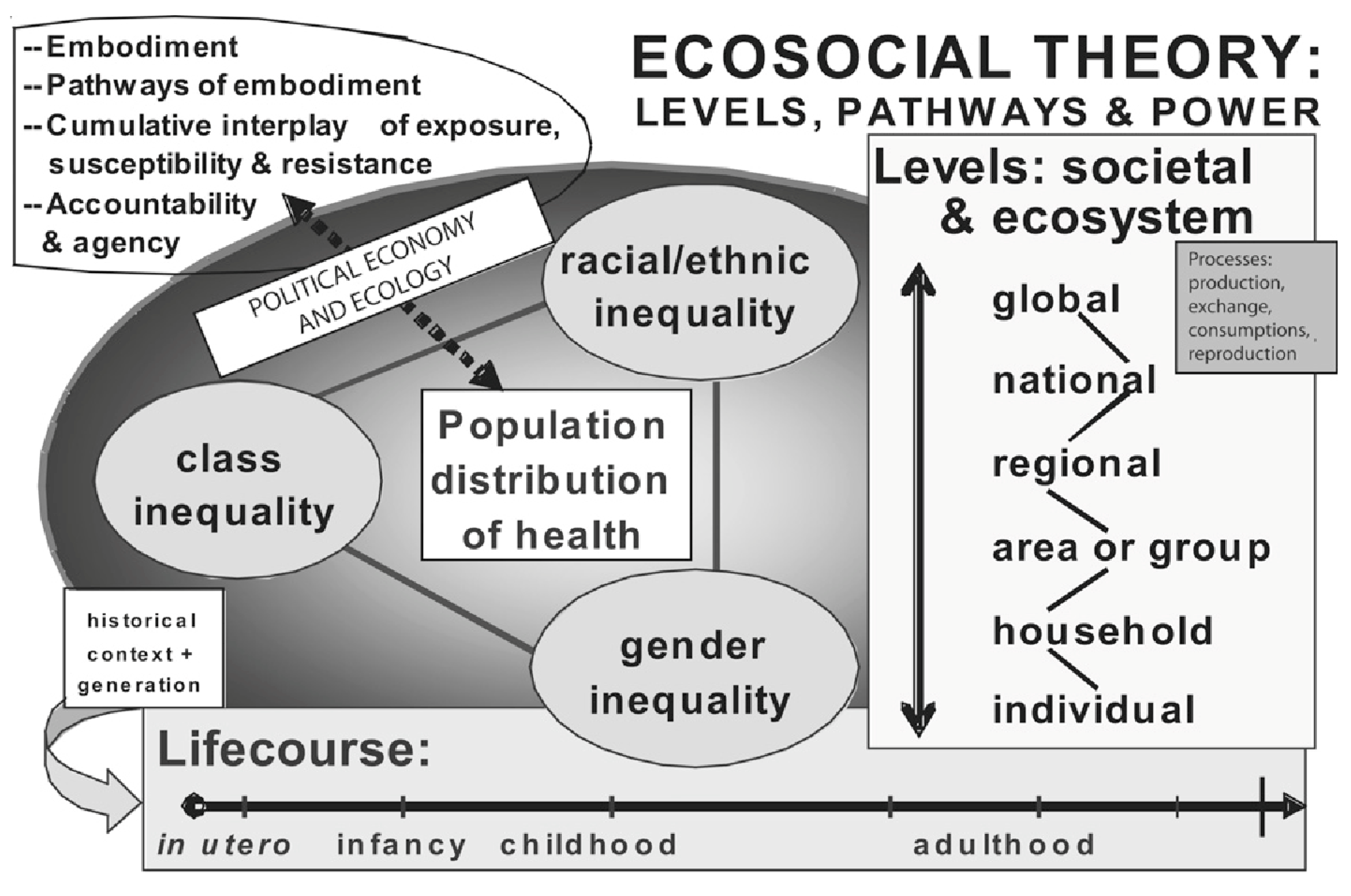

2.1. Research Design

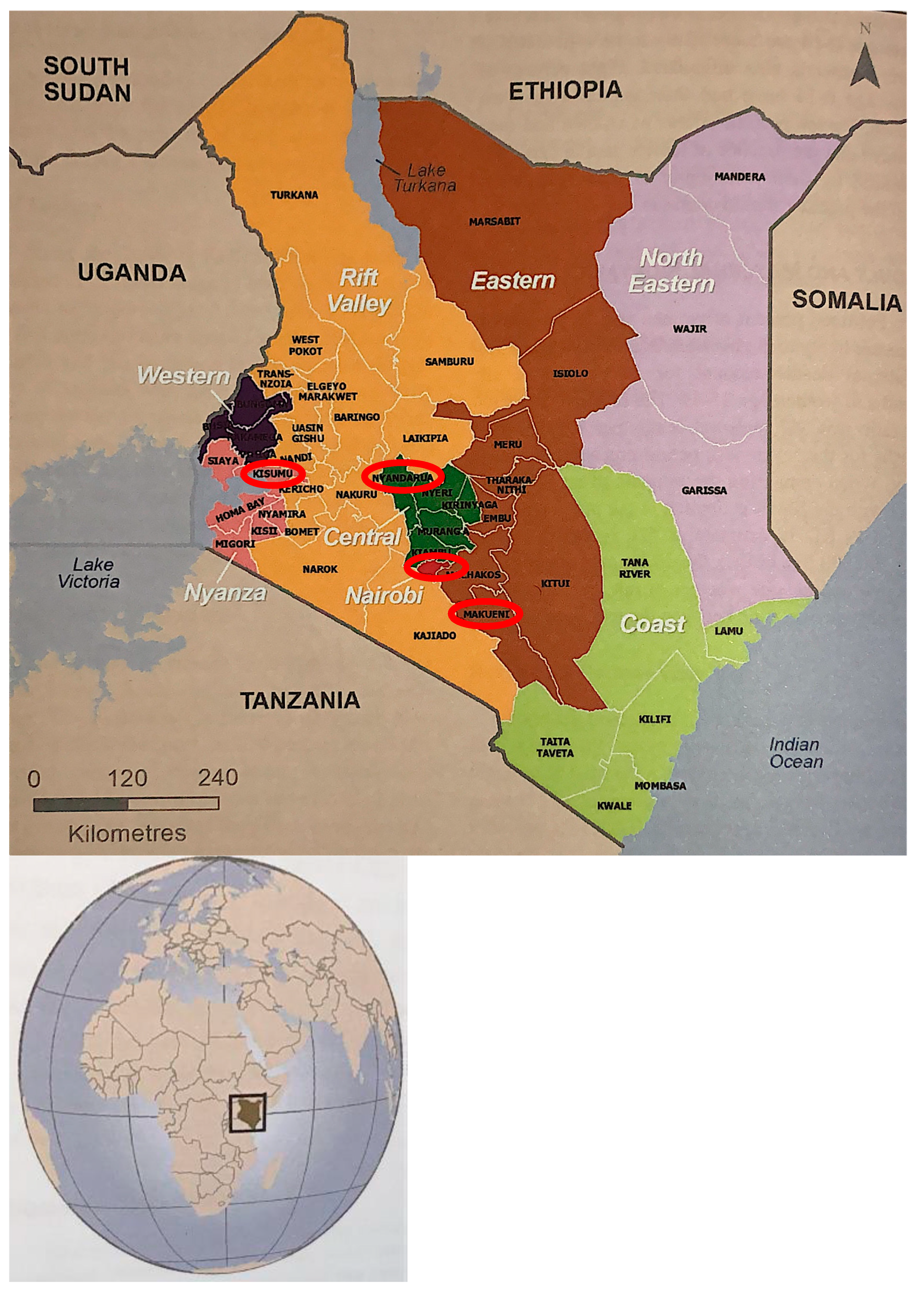

2.2. Selection of Study Site

2.3. Selection of Participant Recruitment

2.4. Data Collection Methods

2.5. Data Management and Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Perceptions, Meanings, and Social Construction of a Healthy Community and Good Life

3.2. Economic and Living Standards Factors

“You know when you have money, you will buy for your family the food that they want and that will make them healthy and the community at large”. In Makueni County, similar sentiments were echoed where a participant in a male FGD described a healthy community as one where “the people are able to raise their children well by providing them shelter, education, and also food”.(female youth in Makueni County)

“If we have a source of income that that will make us have a good life and healthy community…job availability can bring a good life. I talk of employment, if you got employment, employment would make our life, or our health become better. This one will result into a healthy community”.(female youth in Kisumu County)

3.3. State of the Environment and Neighborhood Effect

“I can say that the community we are living in is not healthy, the health status is not good because the environment is not conducive…most of the people from this area fetch water from the river…and water…is polluted. It is not clean. This one leads to many people suffering from different diseases, such as bilharzia, those waterborne diseases. Also, there is unreliable rainfall throughout the year…people experience famine and drought…the cattle or the livestock are not surviving they are dying…there is low production of food…so, shortage of food also leads to malnutrition of the youths, the young children, and the aged, so that one makes life too difficult and the community unhealthy”.(FGD—male youth in Makueni County)

3.4. Social Relationships and Interactions

“In this community, we have youth groups where we contribute money together. Through this, we have access to loans of up to KSh. 100,000 (≈USD 1,000). When we get this money, they use it to buy land which is subdivided amongst the group members or this money is used in different developments. This is helpful to us as young people”.(FGD—female youth in Nyandarua County)

“For our community to be healthy, we need to have a component of love. We need to love one another…so that in case one of us is unable to send their child to school, the community can come together…to help this child get education. By doing so, we will find that such children can come back and help her society”.(FGD—female youth in Kisumu County)

3.5. Community Health Status and Girls as “Bleeding Bodies”

“STIs, maybe gonorrhea, this comes from the point of pleasures for young people…We are not accessing condoms; we end up getting infected with STIs”.(FGD—male youth in Nyandarua County)

“Wanting to enjoy life responsibly and fear of the monthly period. Provision of sanitary towels is something that…is a challenge to the girls in this community, especially when they start to get such changes, we start to have certain fears”.(ID—female youth in Kisumu County)

“For me, it has brought me a serious challenge…when I asked my grandmother for this stuff, she was always saying that she had no money to buy such kind of things. So, I had to look for money to get sanitary towels…I was forced to get a boyfriend. He used to buy me pads and that’s how I ended up conceiving [deep breath] and marriage [was] the only option”.(IDI—female youth in Kisumu County)

3.6. Parental Guidance Gap and “Untrustworthy Bodies”

“…the parent does not have time for the youth, for that matter. And then most of them die from inside, they just keep quiet, they think it will heal over time”.(IDI—male youth in Langata)

“People are committing suicides every now and then. Find that a young man has committed suicide because of a lady he wanted to marry…Some of them, they commit suicide because of the issues that emanate from the house or just because of relationships”.(FGD—female youth in Kisumu County)

“You will find that we are denied freedom of interaction…you are a girl, so your life is that of being held in the house. You are taken to school and brought back home, and you are enclosed indoors”.(FGD—female youth in Langata)

“Lack of trust within the community. You will find that if you rear chicken and you want to sell it in the market, people will ask you, where have you gotten this chicken? It is like people believe that us as youth, we steal from other places. So, getting a market for our produce…a challenge in this community. This affects us”.(FGD—male youth in Nyandarua County)

3.7. Culturally Disadvantaged Bodies

“For the young adults and the teenagers, they’re people who want to look like others. They want to be like celebrities, so they tend to behave, dress like them…I can say the lifestyle here is more of experimenting because people are not taught about self-awareness and this exerts social pressure on the youth”.(CBO representative who was a youth working with youths in Kibera)

“Like now in my community, if I give birth to a child out of wedlock and the man damps me and, in my home, I am not given land, this brings what I would call multiple problems…I will not be able to start off my life again and even do some farming to take care of my children…it is a real challenge to us as girls”.(FGD—female youth in Langata)

3.8. Bodies at Risk of Political Misuse and Emotional Suffering

“I used to engage in politics sometimes, but I want to testify that I left it. There is a time we went for campaign for one of the candidates and chaos erupted. On that day, I just escaped death narrowly. From that time, I said never, never again to engage in matters of politics”.(FGD—female youth in Kisumu County)

“The politicians, they take advantage over us because we are poor and have nothing. We sell our votes for about 3000/– ($30). So, our votes do not have the power to vote out a bad leader because you have already sold your vote”.(FGD—male youth in Kibera)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. The Sustainable Development Goals Report; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Brolan, C.E.; Hussain, S.; Friedman, E.A.; Ruano, A.L.; Mulumba, M.; Rusike, I.; Beiersmann, C.; Hill, P.S. Community participation in formulating the post-2015 health and development goal agenda: Reflections of a multi-country research collaboration. Int. J. Equity Health 2014, 13, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehling, M.; Nelson, B.D.; Venkatapuram, S. Limitations of the Millennium Development Goals: A literature review. Glob. Public Health 2013, 8, 1109–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lansford, J.E.; Banati, P. Handbook of Adolescent Development Research and Its Impact on Global Policy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, G.; Sawyer, S.M.; Santelli, J.S.; A Ross, D.; Afifi, R.; Allen, N.B.; Arora, M.; Azzopardi, P.; Baldwin, W.; Bonell, C.; et al. Our future: A Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet 2016, 387, 2423–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilletti, E.; Banati, P. Making Strategic Investments in Adolescent Wellbeing, in Handbook of Adolescent Development Research and Its Impacts on Global Policy; Lasford, J.E., Banati, P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 299–318. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan, P.; Sweeny, K.; Rasmussen, B.; Wils, A.; Friedman, H.S.; Mahon, J.; Patton, G.C.; Sawyer, S.M.; Howard, E.; Symons, J.; et al. Building the foundations for sustainable development: A case for global investment in the capabilities of adolescents. Lancet 2017, 90, 1792–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckersley, R. A new narrative of young people’s health and well-being. J. Youth Stud. 2011, 14, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancet, T. Better understanding of youth mental health. Lancet 2017, 389, 1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landstedt, E.; Coffey, J.; Wyn, J.; Cuervo, H.; Woodman, D. The Complex Relationship between Mental Health and Social Conditions in the Lives of Young Australians Mixing Work and Study. Young 2016, 25, 339–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Campbell, W.K.; Freeman, E.C. Generational differences in young adults’ life goals, concern for others, and civic orientation, 1966–2009. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 102, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlong, A.; Woodman, D.; Wyn, J. Changing times, changing perspectives: Reconciling ‘transition’ and ‘cultural’ perspectives on youth and young adulthood. J. Sociol. 2011, 47, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, A.; Bliuc, A.-M.; Molenberghs, P. The social contract revisited: A re-examination of the influence individualistic and collectivistic value systems have on the psychological wellbeing of young people. J. Youth Stud. 2019, 23, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DHS. Demographic Health Survey Data. 2016. Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm (accessed on 5 December 2018).

- Ushie, A.B.; Udoh, E.E. Where are we with young people’s wellbeing? Evidence from Nigerian Demogrphic and Health Survey. Soc. Ind. Res. 2016, 129, 803–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborn, T.L.; Venturo-Conerly, K.E.; Wasil, A.R.; Schleider, J.L.; Weisz, J.R. Depression and Anxiety Symptoms, Social Support, and Demographic Factors Among Kenyan High School Students. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019, 29, 1432–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, S.M.; Patton, G.C. Health and Wellbeing of Adolescence: A Dynamic Profile, in Handbook of Adolescent Development Research and Its Impact on Global Policy; Lansford, J.E., Banato, P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York City, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Godia, P.; Olenja, J.; Hofman, J.J.; Broek, N.V.D. Young people’s perception of sexual and reproductive health services in Kenya. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, L.; Nyothach, E.; Alexander, K.; Odhiambo, F.O.; Eleveld, A.; Vulule, J.; Rheingans, R.; Laserson, K.F.; Mohammed, A.; Phillips-Howard, P.A. ‘We Keep It Secret So No One Should Know’—A Qualitative Study to Explore Young Schoolgirls Attitudes and Experiences with Menstruation in Rural Western Kenya. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e79132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, K.T.; Oduor, C.; Nyothach, E.; Laserson, K.F.; Amek, N.; Eleveld, A.; Mason, L.; Rheingans, R.; Beynon, C.; Mohammed, A.; et al. Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Conditions in Kenyan Rural Schools: Are Schools Meeting the Needs of Menstruating Girls? Water 2014, 6, 1453–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beguy, D.; Mumah, J.N.; Gottschalk, L. Unintended Pregnancies among Young Women Living in Urban Slums: Evidence from a Prospective Study in Nairobi City, Kenya. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e101034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osok, J.; Kigamwa, P.; Van Der Stoep, A.; Huang, K.-Y.; Kumar, M. Depression and its psychosocial risk factors in pregnant Kenyan adolescents: A cross-sectional study in a community health Centre of Nairobi. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luseno, W.; Field, S.H.; Iritani, B.J.; Odongo, F.S.; Kwaro, D.; Amek, N.O.; Rennie, S. Pathways to Depression and Poor Quality of Life Among Adolescents in Western Kenya: Role of Anticipated HIV Stigma, HIV Risk Perception, and Sexual Behaviors. Aids Behav. 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitome, J.W.; Katola, M.T.; Nyabwari, B.G. Correlation between students’ discipline and performance in Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2013, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Mutua, M. Review: Kenya’s Quest for Democracy: Taming the Leviathan. J. Afr. Elect. 2008, 7, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasongo, J.W.; Wamocha, L.M.; Achok, J.S.K. Could forgiveness and amnesty be a panacea for Kenya’s post-election conflic era? In Managing Conflicts in Africa’s Democratic Transitions; Adebayo, A.G., Ed.; Lexington Books: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, M.J. Conflict analysis of the 2007 Post-Election Violence in Kenya. In Managing Conflicts in Africa’s Democratic Transitions; Adebayo, A.G., Ed.; Lexington Books: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2012; pp. 141–154. [Google Scholar]

- Bold, T.; Kimenyi, M.; Mwabu, G.; Sandefur, J. Can Free Provision Reduce Demand for Public Services? Evidence from Kenyan Education *. World Bank Econ. Rev. 2014, 29, 293–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afande, F.; Maina, W.; Maina, M.P. Youth Engagement in Agriculture in Kenya: Challenges and Prospects. J. Cult. Soc. Dev. 2015, 7, 4–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. The Kenya Economic Survey—2018; KNBS, Ed.; Kenya National Bureau of Statistics: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger, N. Epidemiology and the People’s Health; Oxford University Press (OUP): Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker, S.A. Diabetes and the off-reserve Aboriginal Population in Canada, in Master of Science in Social Dimensions of Health Programs; University of Victoria: Britisch, Columbia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Richmond, C. The social determinants of Inuit health: A focus on social support in the canadian arctic. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2009, 68, 471–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richmond, C.; Ross, N.A. The determinants of First Nation and Inuit health: A critical population health approach. Health Place 2009, 15, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A.; Strauss, A.L. Basics of Qualitative Research; SAGE Publications: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Guba, E.G.; Lincoln, Y.S. Competing Paradigms in Qualitative Research: Theories and Issues, in Approaches to Qualitative Research: A Reader on Theory and Practice; Hesse-Biber, S.N., Leavy, P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, S.J.; Eyles, J.; DeLuca, P. Mapping health in the Great Lakes areas of concern: A user-friendly tool for policy and decision makers. Environ. Health Perspect 2001, 109 (Suppl. S6), 817–826. [Google Scholar]

- Eyles, J.; Brimacombe, M.; Chaulk, P.; Stoddart, G.; Pranger, T.; Moase, O. What determines health? To where should we shift resources? Attitudes towards the determinants of health among multiple stakeholder groups in Prince Edward Island, Canada. Soc. Sci. Med. 2001, 53, 1611–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awiti, A.; Scott, B. The Kenya Youth Survey Report; East Africa Institute, The Aga Khan University: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children’s Fund. The State of the World’s Children 2016: A Fair Chance for Every Child; United Nations Children’s Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1–180. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics and ICF Macro. Kenya Demographic Health Survey 2013–14; KNBS and ICF Macro: Calverton, MD, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. The world youth report: Youth and the agenda 2030 for sustainable development. In World Youth Report; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–252. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, I. Qualitative research methods. In Human Geography, 4th ed.; Hay, I., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Møller, V.; Roberts, B.; Zani, D. The National Wellbeing Index in the IsiXhosa Translation: Focus Group Discussions on How South Africans View the Quality of Their Society. Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 135, 167–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, P.; Peasgood, T.; White, M. Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective well-being. J. Econ. Psychol. 2008, 29, 94–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangmennaang, J.; Elliott, S.J. ‘Wellbeing is shown in our appearance, the food we eat, what we wear, and what we buy’: Embodying wellbeing in Ghana. Health Place 2019, 55, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommer, M. Structural factors influencing menstruating school girls’ health and well-being in Tanzania. Comp. A J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2013, 43, 323–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, S.A.; Winch, P.J.; Caruso, B.; Obure, A.F.; A Ogutu, E.; A Ochari, I.; Rheingans, R.D. ‘The girl with her period is the one to hang her head’ Reflections on menstrual management among schoolgirls in rural Kenya. Bmc Int. Health Hum. Rights 2011, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, M.; Mmari, K. Addressing Structural and Environmental Factors for Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 1973–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viner, R.M.; Ozer, E.M.; Denny, S.; Marmot, M.; Resnick, M.; Fatusi, A.; Currie, C. Adolescence and the social determinants of health. Lancet 2012, 379, 1641–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVore, E.R.; Ginsburg, K.R. The protective effects of good parenting on adolescents. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2005, 17, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glozah, F.N. Exploring Ghanaian adolescents’ meaning of health and wellbeing: A psychosocial perspective. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2015, 10, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sher-Censor, E.; Parke, R.D.; Coltrane, S. Parents’ Promotion of Psychological Autonomy, Psychological Control, and Mexican–American Adolescents’ Adjustment. J. Youth Adolesc. 2010, 40, 620–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricardo, C.; Barker, G.; Pulerwitz, J.; Rocha, V. Gender, Sexual Behavior and Vulnerability Among Young People. In Promoting Young People’s Sexual Health; Ingham, R., Aggleton, P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; pp. 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, M.; Likindikoki, S.; Kaaya, S.F. Boys’ and young men’s perspectives on violence in Northern Tanzania. Cult. Health Sex. 2013, 15, 695–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Eckersley, R. Beyond inequality: Acknowledging the complexity of social determinants of health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 147, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mmari, K.; Lantos, H.; Blum, R.W.; Brahmbhatt, H.; Sangowawa, A.; Yu, C.; Delany-Moretlwe, S. A Global Study on the Influence of Neighborhood Contextual Factors on Adolescent Health. J. Adolesc. Health 2014, 55, S13–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allin, P.; Hand, D.J. The Wellbeing of Nations; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

| Data Source | Characteristics | Region/County | Kisumu | Makueni | Nyandarua | Nairobi-Langata † | Nairobi-Kibera ‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FGD participants | Age (range) | 15–24 | 20 (17–24) | 17 (16–19) | 17 (18–24) | 11 (17–24) | 21 (18–24) |

| No. of FGDs | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Gender | Male | 12 | 8 | 9 | 4 | 11 | |

| Female | 8 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 10 | ||

| Education level | Primary and below | 13 | 12 | 2 | 2 | 8 | |

| Secondary and above | 7 | 5 | 15 | 9 | 13 | ||

| Household size | Range | 1–15 | 2–13 | 1–10 | 1–8 | 1–12 | |

| Range of monthly income (in USD) | 0–300 | 0–250 | 0–325 | 0–900 | 0–275 | ||

| IDI participants | No. of IDIs | 4 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | |

| Gender | Male | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| Female | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Household size | Range | 2–13 | 2–10 | 2–5 | 2–8 | 2–5 | |

| Education level | Primary and below | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Secondary and above | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Range of monthly income (in USD) | 5–100 | 50–100 | 10–100 | 5–500 | 5–200 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Onyango, E.O.; Elliott, S.J. Bleeding Bodies, Untrustworthy Bodies: A Social Constructionist Approach to Health and Wellbeing of Young People in Kenya. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7555. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207555

Onyango EO, Elliott SJ. Bleeding Bodies, Untrustworthy Bodies: A Social Constructionist Approach to Health and Wellbeing of Young People in Kenya. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(20):7555. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207555

Chicago/Turabian StyleOnyango, Elizabeth Opiyo, and Susan J. Elliott. 2020. "Bleeding Bodies, Untrustworthy Bodies: A Social Constructionist Approach to Health and Wellbeing of Young People in Kenya" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 20: 7555. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207555

APA StyleOnyango, E. O., & Elliott, S. J. (2020). Bleeding Bodies, Untrustworthy Bodies: A Social Constructionist Approach to Health and Wellbeing of Young People in Kenya. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(20), 7555. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207555