Group Positive Affect and Beyond: An Integrative Review and Future Research Agenda

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

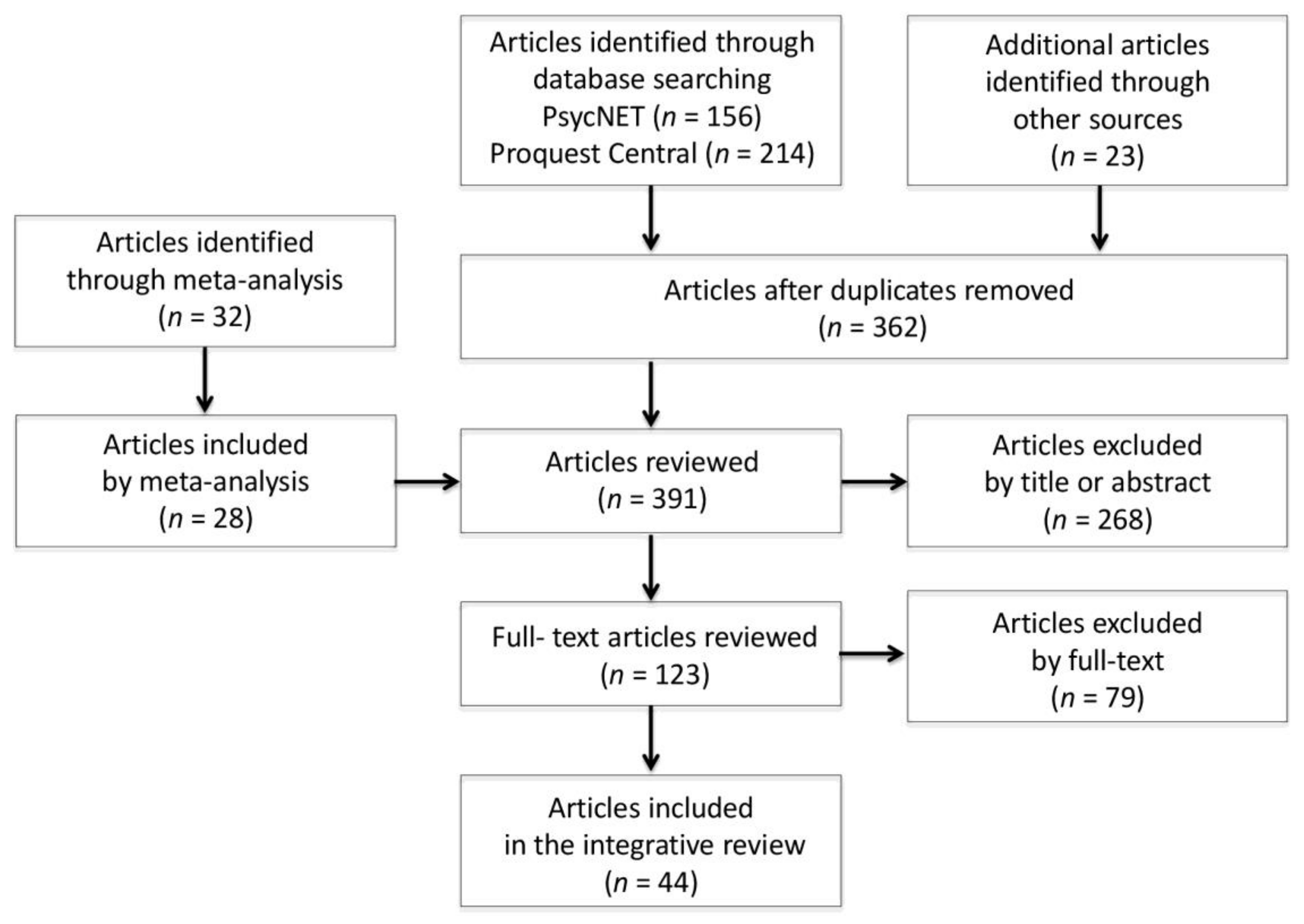

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Search Outcome

2.3. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Research Question 1. How is Group Positive Affect Operationalized?

| Source | n (Groups) | Group Size: Range; M (DT) | Cronbach α Instrument | Design | Composition Model | Agreement | Reliability | Response Rate | Statistical Analysis | Unit of Analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bashshur et al. (2011) [44] | 152–179 | 4.63 (1.84) | 0.96 | Field. LG | DC | AD = 0.54 | ICC1 = 0.23, ICC2 = 0.60 | 79.73–90.12% | Polynomial regression | Group |

| 2 | Bramesfeld & Gasper (2008) [45] | 30 | 3 | 0.94 | Lab. CS | DC | Rwg = 0.75 | UD | UD | ANOVA, Mediation analyses | Group |

| 3 | Bustamante et al. (2014) [46] | 264 | 5 (1.54) | 0.92 | Field. CS | RSC | UD | ICC1 = 0.29, ICC2 = 0.62 | UD | SEM | Group |

| 4 | Chi, & Huang (2014) [47] | 61 | 4.57 (2.52) | 0.93 | Field. CS | DC | Rwg = 0.95 | ICC1 = 0.21, ICC2 = 0.58 | 76% | SEM | Group |

| 5 | Chi, et al. (2011) [17] | 85 | 7.34 (2.80) | 0.89 | Field. CS | DC | Rwg = 0.91 | ICC1 = 0.23 | 69% | SEM | Group |

| 6 | Collins et al. (2015) [48] | Study 1: 61 | Study 1: 3 to 7; 3.59 (.93) | 0.90–0.91 | Lab. LG | DC | Rwg = 0.78 | ICC1 = 0.12, ICC2 = 0.31 | 86.05% | Hierarchical regression | Group |

| Study 2: 47 | Study 2: 3 to 4; 2.64 (.61) | 0.89–0.91 | Lab. LG | DC | Rwg = 0.88 | ICC1 = 0.23, ICC2 = 0.44 | 41.89% | Group | |||

| 7 | Dimotakis et al. (2012) [49] | 21 | 5 | 0.94 | Lab. LG | DC | Rwg = 0.61–0.72 | ICC1 = 0.20, ICC2 = 0.84 | UD | Hierarchical regression | Group |

| 8 | Gamero et al. (2008) [50] | 156 | 4 to 14; 5.83 (1.89) | 0.95 | Field. LG | DC | AD = 0.55–0.58 | ICC1 = 0.19, ICC2 = 0.51–0.52 | 87.7–95.1% | Hierarchical regression | Group |

| 9 | George (1990) [51] | 26 | 2 to 16 | 0.80 | Field. LG | DC | UD | ICC1 = 0.87 | 84.67% | Regression | Group |

| 10 | George (1995) [52] | 41 | 4 to 9 | 0.91 | Field. CS | DC | UD | ICC1 = 0.88 | 72% | Regression | Group |

| 11 | Gil et al. (2015) [53] | 110 | 6.28 (4.4) | 0.92 | Field. CS | RSC | UD | ICC1 = 0.13 | UD | Regression | Group |

| 12 | González-Romá ,& Gamero (2012) [54] | 59 | 3 to 9; 4.39 (1.39) | 0.92 | Field. LG | DC | AD = 0.47 | UD | 95.3–98% | Regression | Group |

| 13 | Hentschel et al. (2013) [55] | 38 | 3 to 19; 8 (4.64) | 0.85 | Field. CS | RSC | Rwg = 0.92 | ICC1 = 0.44, ICC2 = 0.86 | 69.13% | Hierarchical regression | Group |

| 14 | Hmieleski et al. (2011) [34] | 179 | 51 | 0.91 | Field. LG | RSC | Rwg = 0.81–0.72 | UD | 11.8% | Hierarchical regression, bootstrapping | Group, organization |

| 15 | Kim et al. (2016) [56] | 50 | UD | 0.86 | Field. CS | RSC | Rwg = 0.84 | ICC1 = 0.12, ICC2 = 0.44 | 82% | Hierarchical regression | Group, individual |

| 16 | Kim, & Shin (2015) [57] | 97 | 6.1 (2.1) | 0.84 | Field. CS | DC | Rwg = 0.85 | ICC1 = 0.15, ICC2 = 0.47 | 80% | Hierarchical regression | Group |

| 17 | Kim et al. (2013) [58] | 42 | 3 to 15; 6.21 (3) | 0.87 | Field. CS | DC | Rwg = 0.93 | ICC1 = 0.19, ICC2 = 0.63 | 74% | HLM | Group, individual |

| 18 | Klep et al. (2011) [59] | 70 | 3 | 0.93 | Lab. CS | DC | Rwg = 0.86 | ICC1 = 0.54, ICC3 = 0.97 | UD | ANOVA | Group |

| 19 | Knight (2015) [60] | 33 | 10 to 17; 11.54 (1.33) | UD | Field. LG | RSC | Rwg = 0.90–0.92 | ICC1 = 0.08–0.09, ICC2 = 0.43–0.47 | 74–94% | Growth models, regression | Group |

| 20 | Lee et al. (2016) [61] | 100 | 3 to 17 | 0.83 | Field. LG | RSC | Rwg = 0.91 | ICC1 = 0.32, ICC2 = 0.69 | UD | Regression | Group |

| 21 | Levecque, et al. (2014) [62] | 97 | UD | 0.81 | Field. CS | DC | AD = 0.67, Rwg = 0.84 | ICC1 = 0.24, ICC2 = 0.70 | 81.6% | Hierarchical logistic regression | Group, individual |

| 22 | Lin et al. (2014) [63] | 47 | 6.5 | 0.88 | Field. CS | DC | Rwg = 0.95 | ICC1 = 0.25, ICC2 = 0.59 | 63.1% | Hierarchical regression | Group |

| 23 | Mason (2006) [64] | 24 | 3 to 25; 7.66 (5.06) | 0.83 | Field. CS | DC | Rwg = 0.79 | ICC1 = 0.09 | >75% | Semipartial correlations | Group |

| 24 | Mason, & Griffin (2003) [65] | 97 | 3 to 30; 15.58 (7.80) | 0.88–0.89 | Field. LG | RSC | Rwg = 0.85 | ICC1 = 0.21–0.22, ICC2 = 0.59–0.69 | 73% | HLM | Group, individual |

| 25 | Mason, & Griffin (2005) [66] | 55–66 | 3 to 30; 9.32 | UD | Field .CS | RSC | Rwg = 0.63 | UD | 66.5% | Hierarchical regression | Group |

| 26 | Meneghel, et al. et al. (2014) [15] | 216 | 2 to 38; 4.99 (4.20) | UD | Field. CS | RSC | AD = 0.10–0.14 | ICC1 = 0.72–0.97 | UD | SEM | Group |

| 27 | Paulsen et al. (2016) [67] | 34 | UD | 0.75–0.92 | Lab. LG | DC | Rwg = 0.78 | UD | UD | MSEM | Group |

| 28 | Peñalver et al. (2019) [13] | Study 1: 112 | Study 1: 2 to 5 | 0.93 | Lab. CS | RSC | AD = 0.54–0.59 | ICC1 = 0.10–0.18 | UD | SEM | Group |

| Study 2: 417 | Study 2: 2 to 35; 5.14 (4.4) | 0.93 | Field. CS | RSC | AD = 0.92–0.94 | ICC1 = 0.13–0.16 | UD | Group | |||

| 29 | Rego et al. (2014) [35] | 106 | 12.2 (6.89) | 0.71 | Field. CS | RSC | UD | UD | 66% | Path analysis approach | Group |

| 30 | Salanova et al. (2011) [16] | 19 | 4 to 7 | 0.70–0.85 | Lab. LG | RSC | Rwg = 0.84–0.89 | UD | UD | SEM | Group |

| 31 | Sánchez-Cardona et al. (2018) [68] | 130 | 2 to 18; 5 | 0.89 | Field. CS | RSC | Rwg = 0.75 | ICC1 = 0.33, ICC2 = 0.68 | UD | SEM | Group |

| 32 | Seong & Choi (2014) [69] | 96 | 3 to 21; 10.35 (4.91) | 0.96 | Field. CS | RSC | Rwg = 0.94 | ICC1 = 0.11, ICC2 = .53 | 85.7% | SEM | Group |

| 33 | Shin (2014) [70] | 98 | 4 to 11; 5.8 (2.4) | 0.88 | Field. CS | DC | Rwg = 0.84 | ICC1 = 0.19, ICC2 = 0.58 | 72% | SEM | Group |

| 34 | Shin et al. (2019) [71] | 116 | 3 to 11; 5.58 (2.2) | 0.95 | Field. CS | DC | Rwg = 0.94 | ICC1 = 0.11, ICC2 = 0.45 | 68% | HLM | Group |

| 35 | Sy and Choi (2013) [72] | 102 | 3 to 5 | UD | Lab. LG | DC | Rwg = 0.49–0.84 | ICC1 = 0.29–0.55, ICC2 = 0.65–0.88 | UD | Hierarchical regression | Group |

| 36 | Tang, & Naumann (2016) [73] | 47 | UD | UD | Field. CS | DC | Rwg = 0.90 | UD | 60.3% | HLM | Group |

| 37 | Tangue et al. (2010) [74] | 71 | 2 to 4 | 0.71 | Field. CS | DC | Rwg = 0.89 | ICC1 = 0.09, ICC2 = 0.19 | UD | Hierarchical regression | Group |

| 38 | Teng, & Luo (2014) [75] | 123 | 2 to 5 | 0.74 | Field. CS | DC | Rwg = 0.71–0.99 | UD | 96.1% | SEM | Group |

| 39 | Tran et al. (2012) [76] | 20 | 4 to 8; 5.3 | UD | Lab. LG | DC | IRR = 0.95–0.98 | ICC = 0.12–0.46 | UD | Correlations, non-parametric test | Group |

| 40 | Tsai et al. (2011) [77] | 68 | 5.9 (2.5) | 0.88 | Field. CS | DC | Rwg = 0.92–0.95 | ICC1 = 0.13, ICC2 = 0.45 | 71% | HLM | Group |

| 41 | Tu (2009) [78] | 106 | 3 to 9; 5.71 | 0.92 | Field. CS | DC | Rwg =0.92 | ICC1 = 0.33, ICC2 = 0.78 | 17.2% | HLM | Group |

| 42 | Van Knippenberg et al. (2010) [79] | 178 | 3 | 0.89 | Lab. CS | DC | Awg = 0.19 | UD | UD | Regression | Group |

| 43 | Volmer (2012) [80] | 21 | 3 | 0.88 | Lab. CS | DC | Rwg = 0.72 | UD | UD | HLM | Group, individual |

| 44 | Zhang et al. (2017) [81] | 74 | 4.39 | 0.88 | Field. CS | DC | Rwg = 0.88 | ICC1 = 0.26, ICC2 = 0.68 | UD | HLM | Group, individual |

| Source | Term | Instrument | Sample | Independent Variable | Moderator Variable | Mediator Variable | Dependent Variable | Informant (Variable) | Country | Journal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bashshur et al. (2011) [44] | Team positive affect | Affective Well-being Scale [42] | Employees in different branches of three savings banks in the same geographical region | Team climate, Manager perception of team climate | Group positive affect | Managers (Team climate) | Spain | Applied Psychology | ||

| 2 | Bramesfeld & Gasper (2008) [45] | Happy mood | UD | Students from a course | Mood manipulation (e.g., Group positive affect), Evidence distribution | Focus on the evidence | Group performance | Objective (Group performance) | U.S.A | Universitas Psychologica | |

| 3 | Bustamante et al. (2014) [46] | Positive emotions | HERO [39] | Employees from service sector | Empathy | Positive emotions | Quality of service | Managers (Quality of service) | Spain | Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología Positiva | |

| 4 | Chi & Huang (2014) [47] | Positive group affective tone | Positive and Negative Affect Schedule [38] | Research and development (R&D) teams from high-technology firms | Transformational leadership | Team learning goal orientation, Team avoiding goal orientation, Group positive affect, Negative group affective tone. | Team performance | Managers (Team performance) | Taiwan | Group & Organization Management | |

| 5 | Chi et al. (2011) [17] | Positive group affective tone | Positive and Negative Affect Schedule [38] | Sales teams from five insurance firms | Leader positive moods | Group positive affect, Transformational Leadership, Team goal commitment, Team satisfaction, Team helping behaviors. | Team performance | Leaders (Leader positive moods, Team performance), Organizational database (Team performance) | Taiwan | Small Group Research | |

| 6 | Collins et al. (2015) [48] | Positive affective tone (Study 1) | Positive and Negative Affect Schedule [38] | University students completing a business communication course | Group positive affect | Management of others’ emotions. | Team improvement; Team task | Objective (Team improvement, Team task) | Australia | Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes | |

| Positive affective tone (Study 2) | Positive and Negative Affect Schedule [38] | University students frombusiness course | Group positive affect | Management of others’ emotions | Team performance | Objective (Team performance) | The Journal of Creative Behavior | ||||

| 7 | Dimotakis et al. (2012) [49] | Positive affect | Positive and Negative Affect Schedule [38] | University students | Regulatory focus, Team structure, Task characteristics | Team structure | Helping behaviors, Group positive affect | Task performance, Task satisfaction | U.S.A | Journal of Management & Organization | |

| 8 | Gamero et al. (2008) [50] | Affective climate. Enthusiasm climate | Affective Well-being Scale [42] | Employees from saving banks | Task Conflict T1, Group positive affect T1 | Relationship conflict T2 | Group positive affect T2 | Spain | British Journal of Management | ||

| 9 | George (1990) [51] | Positive affective tone of the work group | Job Affect Scale [40] | Salespeople working for a large department store | Negative affective tone, Group positive affect, Commission | Prosocial Behavior, Absence | Organization (Absenteeism) | U.S.A | The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher | ||

| 10 | George (1995) [52] | Group positive affective tone | Modified Positive and Negative Affect Schedule [38] | Salespeople from a retail organization | Leader positive mood, Group positive affect | Group performance | Sales manager (group performance, leader positive mood) | U.S.A | Revista de Psicología Del Trabajo y de Las Organizaciones | ||

| 11 | Gil et al. (2015) [53] | Positive affect in work teams | HERO [39] | Employees from service organizations | Work team size, Economic sector, Gender, Type of contract, Organizational tenure | Group positive affect | Spain | Journal of Organizational Behavior | |||

| 12 | González-Romá & Gamero (2012) [54] | Positive team mood | Affective Well-being Scale [42] | Branches from a saving bank | Support climate | Group positive affect | Team members’ perceived team performance, Managers’ team effectiveness ratings | Branch Manager (team performance) | Spain | Industrial Marketing Management | |

| 13 | Hentschel et al. (2013) [55] | Positive team affective tone | Job-Related Affective Well-Being Scale [43] | Different sectors (e.g., manufacturing, and technological, administration, medical) | Perceived diversity | Diversity beliefs | Group positive affect, Negative team affective tone | Team identification, Relationship conflict | Germany | Organization Science | |

| 14 | Hmieleski et al. (2011) [34] | Positive team affective tone | Job-Related Affective Well-Being Scale [43] | CEOs of top management teams from new firms | Shared authentic leadership | Group positive affect | Firm performance | CEOs (Shared authentic leadership, Group positive affect), Dun and Bradstreet database (Firm performance) | U.S.A | Administrative Sciences | |

| 15 | Kim et al. (2016) [56] | Positive affective climate | Affective Circumplex [82] | Employees with different job position | Positive trait affect, Negative trait affect, Group positive affect, Group reflexivity | Group positive affect, Group reflexivity | Employee creativity | Supervisor (employee creativity) | Korea | Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal | |

| 16 | Kim & Shin (2015) [57] | Group positive affect | Positive and Negative Affect Schedule [38] | Employee from different size and sector organizations | Cooperative group norms, Group positive affect | Collective efficacy | Team creativity | Team leader (team creativity) | Korea | Applied Psychology | |

| 17 | Kim et al. (2013) [58] | Group trait positive affect | Positive and Negative Affect Schedule [38] | Office workers across different industries (telemarketing, financial, pharmaceutical, and media industries) | Individual trait positive affect | Group positive affect, Group positive affect diversity | Commitment, Job satisfaction, OCB | Korea | Universitas Psychologica | ||

| 18 | Klep et al. (2011) [59] | Positive mood | Self-constructed | Dutch University students | Manipulation work group mood (e.g., Group positive affect), Interactive affectivesharing | Work group performance, Group belongingness, Group information sharing | Observers (Group belongingness, Group information sharing), Objective (Work group performance) | Netherlands | Group & Organization Management | ||

| 19 | Knight (2015) [60] | Team positive mood | Circumplex model of affect [41] | Members from a military academy | Group positive affect, Time | Team exploratory search | Team exploratory search, Team performance | Objective (Team performance) | U.S.A | Small Group Research | |

| 20 | Lee et al. (2016) [61] | Group positive affect | Positive and Negative Affect Schedule [38] | Employees in a manufacturing plant from China | Past group performance, Group Vicarious learning, Group social persuasion, Group positive affect | Group Trust | Group efficacy | Group Performance | Organization (group performance) | China | Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes |

| 21 | Levecque et al. (2014) [62] | Affective team climate | UD | Workers in the Volvo Car plant in Ghent, Belgium | Group positive affect, Job demands, Perceived team climate, Job control, Social support | Group positive affect, Perceived team climate, Job control, Social support | Psychological distress | Belgium | The Journal of Creative Behavior | ||

| 22 | Lin et al. (2014) [63] | Positive group affect | Positive and Negative Affect Schedule [38] | MBA alumni for the most recent three years from a local university | Group positive affect, Negative group affect | Group efficacy | Group identification | Taiwan | Journal of Management & Organization | ||

| 23 | Mason (2006) [64] | Positive affect | Job Affect Scale [40] | This sample was diverse and there was wide range in the type of tasks performed by each work group, ranging from patient care (in a hospital) to client service (in a call center) to replenishment of stock (on a factory floor) to management (within a fast-food chain). | Group time, Task variety, Outcome interdependence, Heterogeneity in backgrounds, Gender Diversity, Age Diversity, Communication quality, Cohesion, Task interdependence, Frequency of meetings | Group positive affect | Australia | British Journal of Management | |||

| 24 | Mason & Griffin (2003) [65] | Positive affective tone | Queensland Public Agency Staff Survey [83] | Workers for an Australian state government agency | Group positive affect | Group absenteeism | Organization (Absenteeism) | Australia | The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher | ||

| 25 | Mason & Griffin (2005) [66] | Positive affective tone | Job Affect Scale [40] | Employees from a variety of different industries operating within both the public and private sector, and the functions of the work groups varied widely, from management to customer service to the replenishment of stock on a factory floor | Group task satisfaction, aggregated individual job satisfaction, Group positive affect, Negative affective tone | Civic helping (group and supervisor), Performance (supervisor), Sportsmanship (group and supervisor), Absenteeism norms (group and supervisor) | Supervisor (Performance, Sportsmanship, Civic helping) | Australia | Revista de Psicología Del Trabajo y de Las Organizaciones | ||

| 26 | Meneghel et al. (2014) [15] | Collective positive emotions | HERO [39] | Employees from service, industry and construction sector in Spain | Group positive affect | Team resilience | Team in role performance, Team extra-role performance | Supervisor (Team in role performance, Team extra-role performance) | Spain | Journal of Organizational Behavior | |

| 27 | Paulsen et al. (2016) [67] | Positive group affective tone | Short form of Positive and Negative Affect Schedule [38] | Students from a software engineering course at a German university | Group positive affect, Negative group affective tone, Project phase | Project phase | Team performance (experts), Team performance (self-rated) | Experts (Team performance) | Germany | Industrial Marketing Management | |

| 28 | Peñalver et al. (2019) [13] | Group positive affect (Study 1) | HERO [39] | University students, full time workers from a wide range of occupations and others | Group positive affect | Group social resources | In- performance extra-role performance, and creative performance | In- performance extra-role performance (leader), and creative performance (external evaluators) | Spain | Organization Science | |

| Group positive affect (Study 1) | HERO [39] | Employee from different size and sector organizations | Group positive affect | Group social resources | In- performance extra-role performance | In- performance extra-role performance (supervisor) | Spain | Administrative Sciences | |||

| 29 | Rego et al. (2014) [35] | Positive affective tone | Positive affective tone [84] | Brazilian retail organization | Group positive affect | Negative affective tone | Store creativity | Store performance | Supervisor (Group positive affect, Store creativity), Organization (Store performance) | Portugal | Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal |

| 30 | Salanova et al. (2011) [16] | Collective positive affect | Enthusiasm-depression scale [85,86] | University students | Efficacy beliefs | Group positive affect | Engagement | Spain | Applied Psychology | ||

| 31 | Sánchez-Cardona et al. (2018) [68] | Team positive affect | HERO [39] | Employee from different size and sector organizations | Leader intellectual stimulation | Group positive affect | Team learning | Spain | Universitas Psychologica | ||

| 32 | Seong & Choi (2014) [69] | Group positive affect | Circumplex Model of Affect. [87] | Korean company in the defense industry | Leader positive affect | Group positive affect, Group-level goal fit, Group-level ability fit, Relationship conflict, Task conflict | Group performance | Supervisor (Relationship conflict, Task conflict, Group performance) | Korea | Group & Organization Management | |

| 33 | Shin (2014) [70] | Positive group affective tone | Positive and Negative Affect Schedule [38] | Teams varied in functional areas (e.g., planning and strategy, sales, human resource management and development, research and development, finance and accounting, and marketing) from different organizations | Group positive affect, Negative group affective tone | Team reflexivity, Team promotion focus, Team prevention focus | Team creativity | Leaders (Team creativity) | UD | Small Group Research | |

| 34 | Shin et al. (2019) [71] | Positive group affective tone | Positive and Negative Affect Schedule [38] | Full-time employees from 17 companies in South Korea, representingdiverse firm sizes and industries | Group positive affect | Team leader transformational leadership | Team reflexivity | Team creativity performance, Team change organizational citizenship behavior | Team leader (Team creativity performance, Team change organizational citizenship behavior) | South Korea | The Journal of Creative Behavior |

| 35 | Sy & Choi (2013) [72] | Positive group mood convergence | Job Affect Scale [40] | Students from management courses | Group-Leader affective diversity, Member affective diversity, Mood induction in leaders | Interpersonal attraction toward leader, Interpersonal attraction toward group, Emotional contagion susceptibility | Group positive affect, Negative group mood convergence | Group positive affect, Negative group mood convergence | Leader (Affective diversity, Interpersonal attraction, mood) | U.S.A | Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes |

| 36 | Tang & Naumann (2016) [73] | Team positive mood | Positive and Negative Affect Schedule [38] | Employees in research institutes in China (basic research, high technology R&D, other fields) | Work value diversity | Group positive affect | Knowledge sharing | Team creativity | U.S.A | Journal of Management & Organization | |

| 37 | Tangue et al. (2010) [74] | Positive group affective tone | Circumplex model of affect [41] | Employees from commercially oriented service organizations, such as shops, bars, restaurants, and physiotherapists’ offices, | Group positive affect, Negative group affective tone | Group identification. | Willingnessto engage in OCB, Perceived team performance | British Journal of Management | |||

| 38 | Teng & Luo (2014) [75] | Group affective tone | Positive and Negative Affect Schedule [38] | College students studying hospitality and tourism management. | Perceived social loafing, Perceived social interdependence | Group positive affect | Group productivity, Group final grades | Lecturer (group final grades) | Taiwan | The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher | |

| 39 | Tran et al. (2012) [79] | Achievement emotions, Approach emotions | Emotion Wheel [88] | Managers taking part in executive development seminars | Group positive affect, Positive ratio | Alternative generation, Alternative evaluation | France | Revista de Psicología Del Trabajo y de Las Organizaciones | |||

| 40 | Tsai et al. (2011) [77] | Positive Group Affective Tone | Positive and Negative Affect Schedule [38] | R&D teams from high-technology firms | Group positive affect | Negative Group Affective Tone, Team trust | Team creativity | Leaders (Team creativity) | Taiwan | Journal of Organizational Behavior | |

| 41 | Tu (2009) [78] | Positive affective tone | Positive and Negative Affect Schedule [38] | New product development teams of high-technology firms from the Taiwan Stock Exchange | Group positive affect, Negative affective tone | Organizational support, Organizational control | Team creativity | Supervisor (team creativity) | Taiwan | Industrial Marketing Management | |

| 42 | Van Knippenberg et al. (2010) [79] | Positive mood | UD | University students | Manipulation mood (e.g., Group positive affect) | Trait negative affect | Information elaboration | Decision quality, Information elaboration | Audio-video records (Information elaboration), Objective (Decisión quality) | Netherlands | Organization Science |

| 43 | Volmer (2012) [80] | Group affective tone | UWIST mood adjective checklist [89] | University students | Manipulation of Leader´s mood | Group positive affect | Team Performance, Team potency, Team goal commitment, Individual Mood | Germany | Administrative Sciences | ||

| 44 | Zhang et al. (2017) [81] | Positive group affective tone | Positive and Negative Affect Schedule [38] | Research and development groups employed by high-technology companies located in China | Leader´s psychological capital, Group positive affect | Leader´s psychological capital | Core self-evaluation | Work engagement | Leaders (Leader´s psychological capital) | China | Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal |

3.2. Research Question 2. What are the Antecedents2 of Group Positive Affect?

3.3. Research Question 3. What are the Outcomes2 of Group Positive Affect?

3.4. Research Question 4. Between What Variables do Group Positive Affect Works as a Psychosocial Mechanisms?

3.5. Research Question 5. Under What Circumstances do High Levels of Group Positive Affect Lead to Negative Outcomes?

4. Discussion

4.1. Research Question 1. How is Group Positive Affect Operationalized?

4.2. Research Question 2: What are the Antecedents of Group Positive Affect?

4.3. Research Question 3: What are the Outcomes of Group Positive Affect?

4.4. Research Question 4: Between What Variables do Group Positive Affect Works as a Psychosocial Mechanisms?

4.5. Research Question 5: Under What Circumstances do High Levels of Group Positive Affect Lead to Negative Outcomes?

4.6. Implications for Practice

4.7. Limitations

4.8. Future research Agenda

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barsade, S.G.; Gibson, D.E. Why does affect matter in organizations? Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2007, 21, 36–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, L.F.; Lewis, M.; Haviland, J.M. Handbook of Emotions; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Greenaway, K.H.; Haslam, S.A.; Cruwys, T.; Branscombe, N.R.; Ysseldyk, R.; Heldreth, C. From “we” to “me”: Group identification enhances perceived personal control with consequences for health and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 109, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozlowski, S.W.J.; Bell, B.S. Work groups and teams in organizations. In Handbook of Psychology: Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Wiley-Blackwell: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 333–375. [Google Scholar]

- Group Decision-Making. Available online: https://oxfordre.com/psychology/psychology/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.001.0001/acrefore-9780190236557-e-262 (accessed on 27 September 2020).

- Flood, F.; Klausner, M. High-performance work teams and organizations. In Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Elfenbein, H.A. The many faces of emotional contagion. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 4, 326–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsade, S.G.; Knight, A.P. Group affect. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2015, 2, 21–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menges, J.I.; Kilduff, M. Group emotions: Cutting the gordian knots concerning terms, levels of analysis, and processes. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2015, 9, 845–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research on Managing Groups and Teams. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/publication/issn/1534-0856 (accessed on 1 March 2019).

- Kelly, J.R.; McCarty, M.K.; Ianonne, N. The functions of shared affect in small groups and teams. In Collective Emotions; von Scheve, C., Salmela, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 175–188. [Google Scholar]

- Rhee, S.-Y. Chapter 4 group emotions and group outcomes: The role of group-member interactions. Res. Manag. Groups Teams 2007, 10, 65–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñalver, J.; Salanova, M.; Martínez, I.M.; Schaufeli, W.B. Happy-productive groups: How positive affect links to performance through social resources. J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 14, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Nguyen, K.D.; Fredrickson, B.L. Positive emotions and well-being. In Frontiers of Social Psychology: Positive Psychology; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 29–45. [Google Scholar]

- Meneghel, I.; Salanova, M.; Martínez, I.M.M. Feeling good makes us stronger: How team resilience mediates the effect of positive emotions on team performance. J. Happiness Stud. 2014, 17, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M.; Llorens, S.; Schaufeli, W. “Yes, I can, I feel good, and I just do it!” On gain cycles and spirals of efficacy beliefs, affect, and engagement. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 60, 255–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, N.-W.; Chung, Y.-Y.; Tsai, W.-C. How do happy leaders enhance team success? The mediating roles of transformational leadership, group affective tone, and team processes. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 41, 1421–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M.; Llorens, S.; Martínez, I.M. Organizaciones saludables. In Una Mirada Desde la Psicología Positiva, 1st ed.; Aranzadi: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ashkanasy, N.M.; Humphrey, R.H. Current emotion research in organizational behavior. Emot. Rev. 2011, 3, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsade, S.G.; Gibson, D.E. Group affect. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 21, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.L.; Lawrence, S.A.; Troth, A.C.; Jordan, P.J. Group affective tone: A review and future research directions. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, S43–S62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Buades, E.; Peiró, J.M.; Montañez-Juan, M.I.; Kozusznik, M.W.; Ortiz-Bonnín, S. Happy-productive teams and work units: A systematic review of the ‘happy-productive worker thesis’. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 17, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, A.P.; Eisenkraft, N. Positive is usually good, negative is not always bad: The effects of group affect on social integration and task performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 1214–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhee, S.-Y.; Yoon, H.J. Shared positive affect in workgroups. Shar. Posit. Affect. Workgr. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoor, J.R.; Kelly, J.R. The evolutionary significance of affect in groups: Communication and group bonding. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2004, 7, 398–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kleef, G.A.; Fischer, A.H. Emotional collectives: How groups shape emotions and emotions shape groups. Cogn. Emot. 2015, 30, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pae, C.-U. Why systematic review rather than narrative review? Psychiatry Investig. 2015, 12, 417–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, M.T.; Da Silva, M.D.; De Carvalho, R. Integrative review: What is it? How to do it? Einstein 2010, 8, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, M.A.; George, E. The why and how of the integrative review. Organ. Res. Methods 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lebreton, J.M.; Senter, J.L. Answers to 20 questions about interrater reliability and interrater agreement. Organ. Res. Methods 2007, 11, 815–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliese, P.D. Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analysis. In Multilevel Theory, Research, and Methods in Organizations: Foundations, Extensions, and New Directions (349–381); Klein, K.J., Kozlowski, S.J., Klein, K.J., Kozlowski, S.J., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hmieleski, K.M.; Cole, M.S.; Baron, R.A. Shared authentic leadership and new venture performance. J. Manag. 2011, 38, 1476–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, A.; Júnior, D.R.E.; Cunha, M.P.; Stallbaum, G.; Neves, P. Store creativity mediating the relationship between affective tone and performance. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2014, 24, 63–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, H. Synthesizing Research: A Guide for Literature Reviews, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, D. Functional relations among constructs in the same content domain at different levels of analysis: A typology of composition models. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salanova, M.; Llorens, S.; Cifre, E.; Martínez, I.M.M. We need a hero! Toward a validation of the healthy and resilient organization (HERO) model. Group Organ. Manag. 2012, 37, 785–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brief, A.P.; Burke, M.J.; George, J.M.; Robinson, B.S.; Webster, J. Should negative affectivity remain an unmeasured variable in the study of job stress? J. Appl. Psychol. 1988, 73, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, R.; Diener, E. Promises and problems with the circumplex model of emotion. In Review of Personality and Social Psychology, No. 13. Emotion; Clark, M.S., Ed.; Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1992; pp. 25–59. [Google Scholar]

- Segura, S.L.; González-Romá, V. How do respondents construe ambiguous response formats of affect items? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 956–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Katwyk, P.T.; Fox, S.; Spector, P.E.; Kelloway, E.K. Using the job-related affective well-being scale (JAWS) to investigate affective responses to work stressors. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000, 5, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashshur, M.R.; Hernández, A.; González-Romá, V. When managers and their teams disagree: A longitudinal look at the consequences of differences in perceptions of organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 558–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramesfeld, K.D.; Gasper, K. Happily putting the pieces together: A test of two explanations for the effects of mood on group-level information processing. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 47, 285–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bustamante, M.; Llorens, S.; Acosta, H. Empatía y calidad de servicio: El papel clave de las emociones positivas en equipos de trabajo. Rev. Latinoam. Psicol. Posit. 2014, 1, 6–17. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, N.-W.; Huang, J.-C. Mechanisms linking transformational leadership and team performance. Group Organ. Manag. 2014, 39, 300–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.L.; Jordan, P.J.; Lawrence, S.A.; Troth, A.C. Positive affective tone and team performance: The moderating role of collective emotional skills. Cogn. Emot. 2015, 30, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimotakis, N.; Davison, R.B.; Hollenbeck, J.R. Team structure and regulatory focus: The impact of regulatory fit on team dynamic. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamero, N.; González-Romá, V.; Peiró, J.M. The influence of intra-team conflict on work teams’ affective climate: A longitudinal study. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2008, 81, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.M. Personality, affect, and behavior in groups. J. Appl. Psychol. 1990, 75, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.M. Leader positive mood and group performance: The case of customer service. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 25, 778–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, E.A.; Llorens, S.; Torrente, P. Compartiendo afectos positivos en el trabajo: El rol de la similitud en los equipos. Pensam. Psicológico 2015, 13, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Romá, V.; Gamero, N. Does positive team mood mediate the relationship between team climate and team performance? Psicothema 2012, 24, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hentschel, T.; Shemla, M.; Wegge, J.; Kearney, E. Perceived diversity and team functioning. Small Group Res. 2013, 44, 33–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Choi, J.N.; Lee, K. Trait affect and individual creativity: Moderating roles of affective climate and reflexivity. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2016, 44, 1477–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Shin, Y. Collective efficacy as a mediator between cooperative group norms and group positive affect and team creativity. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2015, 32, 693–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Shin, Y.; Kim, M.S. Cross-level interactions of individual trait positive affect, group trait positive affect, and group positive affect diversity. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 16, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klep, A.; Wisse, B.; Van Der Flier, H. Interactive affective sharing versus non-interactive affective sharing in work groups: Comparative effects of group affect on work group performance and dynamics. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 41, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, A.P. Mood at the midpoint: Affect and change in exploratory search over time in teams that face a deadline. Organ. Sci. 2015, 26, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Stajkovic, A.D.; Sergent, K. A field examination of the moderating role of group trust in group efficacy formation. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2016, 89, 856–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levecque, K.; Roose, H.; Vanroelen, C.; Van Rossem, R. Affective team climate. Acta Sociol. 2013, 57, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-W.; Lin, C.-S.; Huang, P.-C.; Wang, Y.-L. How group efficacy mediates the relationship between group affect and identification. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1388–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, C.M. Exploring the processes underlying within-group homogeneity. Small Group Res. 2006, 37, 233–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, C.M.; Griffin, M.A. Group absenteeism and positive affective tone: A longitudinal study. J. Organ. Behav. 2003, 24, 667–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, C.M.; Griffin, M.A. Group task satisfaction. Group Organ. Manag. 2005, 30, 625–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, H.F.K.; Klonek, F.E.; Schneider, K.; Kauffeld, S. Group affective tone and team performance: A week-level study in project teams. Front. Commun. 2016, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cardona, I.; Soria, M.S.; Llorens-Gumbau, S. Leadership intellectual stimulation and team learning: The mediating role of team positive affect. Univ. Psychol. 2018, 17, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, J.Y.; Choi, J.N. Effects of group-level fit on group conflict and performance. Group Organ. Manag. 2014, 39, 190–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y. Positive group affect and team creativity. Small Group Res. 2014, 45, 337–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Kim, M.; Lee, S.-H. Positive group affective tone and team creative performance and change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior: A moderated mediation model. J. Creative Behav. 2019, 53, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sy, T.; Choi, J.N. Contagious leaders and followers: Exploring multi-stage mood contagion in a leader activation and member propagation (LAMP) model. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2013, 122, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Naumann, S.E. Team diversity, mood, and team creativity: The role of team knowledge sharing in Chinese R & D teams. J. Manag. Organ. 2016, 22, 420–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanghe, J.; Wisse, B.; Van Der Flier, H. The formation of group affect and team effectiveness: The moderating role of identification. Br. J. Manag. 2009, 21, 340–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.-C.; Luo, Y.-P. Effects of perceived social loafing, social interdependence, and group affective tone on students’ group learning performance. Asia Pacific Educ. Res. 2014, 24, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, V.; Páez, D.; Sanchez, F. Emotions and decision-making processes in management teams: A collective level analysis. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Organ. 2012, 28, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.-C.; Chi, N.-W.; Grandey, A.A.; Fung, S.-C. Positive group affective tone and team creativity: Negative group affective tone and team trust as boundary conditions. J. Organ. Behav. 2011, 33, 638–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, C. A multilevel investigation of factors influencing creativity in NPD teams. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2009, 38, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Knippenberg, D.; Bode, H.J.M.K.-D.; Van Ginkel, W.P. The interactive effects of mood and trait negative affect in group decision making. Organ. Sci. 2010, 21, 731–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Volmer, J. Catching leaders’ mood: Contagion effects in teams. Adm. Sci. 2012, 2, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, N.; Qiu, Y. Positive group affective tone and employee work engagement: A multilevel investigation. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2017, 45, 1905–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, N. The discreteness of emotion concepts: Categorical structure in the affective circumplex. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 21, 1012–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, P.M.; Griffin, M.A.; Wearing, A.J.; Cooper, C.L. Manual for the Queensland Public Agency Staff Survey; Public Sector Management Commission: Brisbane, Australia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Turban, D.B.; Stevens, C.K.; Lee, F.K. Effects of conscientiousness and extraversion on new labor market entrants’ job search: The mediating role of metacognitive activities and positive emotions. Pers. Psychol. 2009, 62, 553–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunin, T. The construction of a new type of attitude measure. Pers. Psychol. 1955, 8, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, P. The measurement of well-being and other aspects of mental health. J. Occup. Psychol. 1990, 63, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, J.; Russell, J.A.; Petersona, B.S. The circumplex model of affect: An integrative approach to affective neuroscience, cognitive development, and psychopathology. Dev. Psychopathol. 2005, 17, 715–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherer, K.R. What are emotions? And how can they be measured? Soc. Sci. Inf. 2005, 44, 695–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, G.; Jones, D.M.; Chamberlain, A.G. Refining the measurement of mood: The UWIST mood adjective checklist. Br. J. Psychol. 1990, 81, 17–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In Political Psychology; Informa UK Limited: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 276–293. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, B.L. What good are positive emotions? Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1998, 2, 300–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.M.; King, E.B. Chapter 5 potential pitfalls of affect convergence in teams: Functions and dysfunctions of group affective tone. Team Cohes. Adv. Psychol. Theory Methods Pract. 2007, 10, 97–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.E.; Brett, J.F.; Sessa, V.I.; Cooper, D.M.; Julin, J.A.; Peyronnin, K. Some differences make a difference: Individual dissimilarity and group heterogeneity as correlates of recruitment, promotions, and turnover. J. Appl. Psychol. 1991, 76, 675–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewell, L.N.; Reitz, H.J. Group Effectiveness in Organizations; Scott Foresman: Glenview, IL, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Wirtz, D.; Biswas-Diener, R.; Tov, W.; Kim-Prieto, C.; Choi, D.-W.; Oishi, S. New measures of well-being. Adv. Qual. Life Theory Res. 2009, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T.A.; Cropanzano, R. The happy/productive worker thesis revisited. Res. Pers. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 26, 269–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S.; Bradley, J.C.; Luchman, J.N.; Haynes, D. On the role of positive and negative affectivity in job performance: A meta-analytic investigation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirsky, S.; King, L.; Diener, E. The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychol. Bull. 2005, 131, 803–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.R.; Spoor, J.R. Affective processes. In Group Processes; Levine, J.M., Ed.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 33–53. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneghel, I.; Martínez, I.M.; Salanova, M. Job-related antecedents of team resilience and improved team performance. Pers. Rev. 2016, 45, 505–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldham, G.R.; Hackman, J.R. Not what it was and not what it will be: The future of job design research. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 463–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skakon, J.; Nielsen, K.; Borg, V.; Guzman, J. Are leaders’ well-being, behaviours and style associated with the affective well-being of their employees? A systematic review of three decades of research. Work. Stress 2010, 24, 107–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelloway, E.K.; Barling, J. Leadership development as an intervention in occupational health psychology. Work. Stress 2010, 24, 260–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausina, J.B.; Meca, J.S. Meta-Análisis en Ciencias Sociales y de la Salud; Editorial Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Berdahl, J.L.; Martorana, P. Effects of power on emotion and expression during a controversial group discussion. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 36, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.R.; Spoor, J.R. Naïve theories about the effects of mood in groups: A preliminary investigation. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2007, 10, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Romá, V.; Hernández, A. Multilevel modeling: Research-based lessons for substantive researchers. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2017, 4, 183–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D.; Van Rhenen, W. Job crafting at the team and individual level. Group Organ. Manag. 2013, 38, 427–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, I.M.; Salanova, M. Diversidad generacional y envejecimiento activo en las organizaciones saludables y resilientes. In Psicología Positiva nas Organizaciones e no Trabalho; de Toledo, S., Silva, N., Eds.; Vetor: Sao Paulo, Brazil, 2017; pp. 194–207. [Google Scholar]

- Curşeu, P.L.; Pluut, H.; Boros, S.; Meslec, N. The magic of collective emotional intelligence in learning groups: No guys needed for the spell! Br. J. Psychol. 2014, 106, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, I.M.; Cifre, E. Individual and group antecedents of satisfaction: One lab- multilevel study. An. Psicol. 2016, 32, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Peiró, J.M.; Kozusznik, M.W.; Rodríguez, I.; Tordera, N. The happy-productive worker model and beyond: Patterns of wellbeing and performance at work. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, T.A. Time revisited in organizational behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 1997, 18, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peñalver, J.; Salanova, M.; Martínez, I.M. Group Positive Affect and Beyond: An Integrative Review and Future Research Agenda. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7499. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207499

Peñalver J, Salanova M, Martínez IM. Group Positive Affect and Beyond: An Integrative Review and Future Research Agenda. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(20):7499. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207499

Chicago/Turabian StylePeñalver, Jonathan, Marisa Salanova, and Isabel M. Martínez. 2020. "Group Positive Affect and Beyond: An Integrative Review and Future Research Agenda" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 20: 7499. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207499

APA StylePeñalver, J., Salanova, M., & Martínez, I. M. (2020). Group Positive Affect and Beyond: An Integrative Review and Future Research Agenda. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(20), 7499. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207499