Social-Emotional Profile of Children with and without Learning Disabilities: The Relationships with Perceived Loneliness, Self-Efficacy and Well-Being

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Social Support

1.2. Loneliness

1.3. Self-Efficacy

1.4. Subjective Well-Being

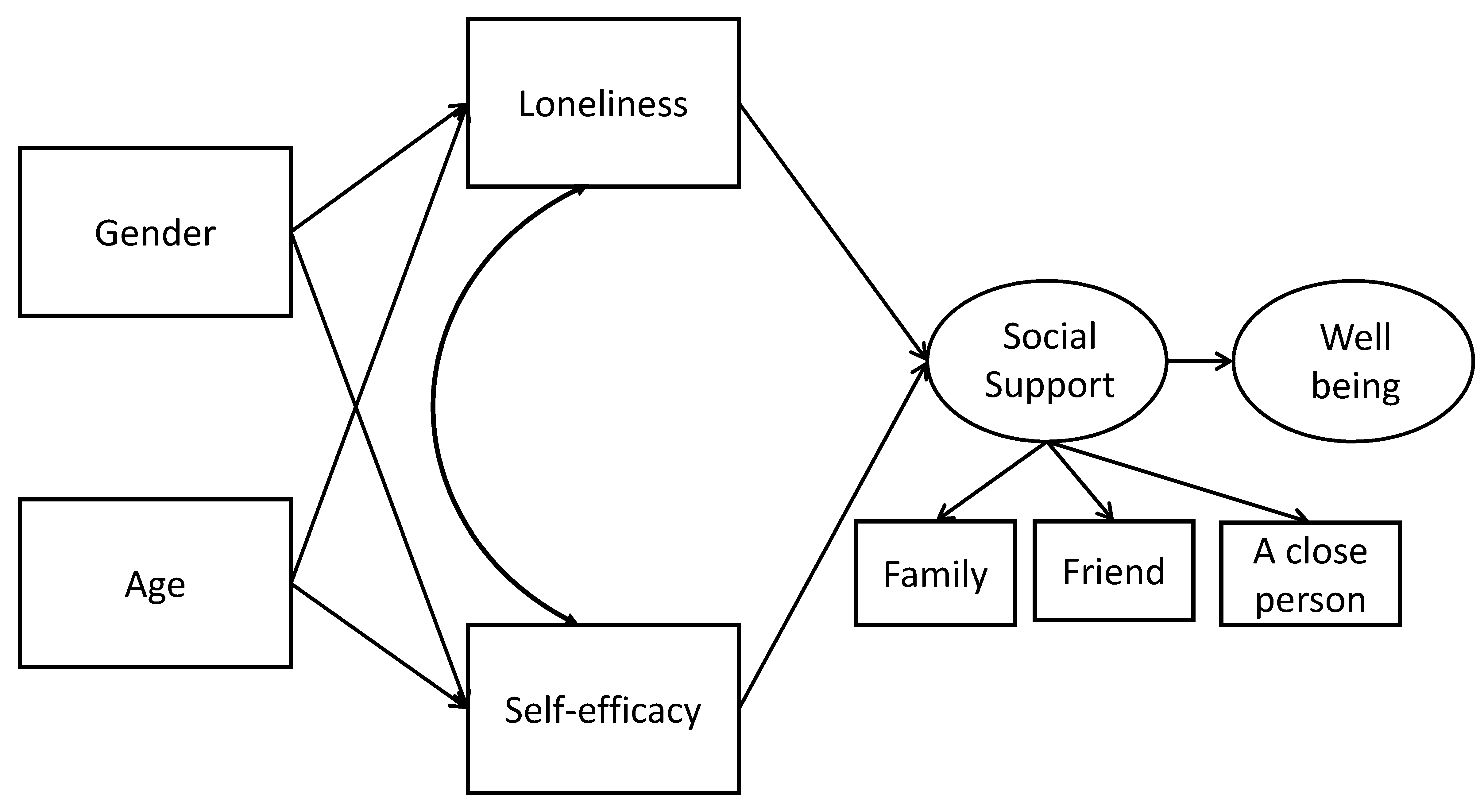

1.5. The Current Study

- We hypothesized that students with LDs would report lower social support, self-efficacy, and well-being, and higher loneliness than non-LD students.

- We hypothesized that higher social support will have mediated the effects of loneliness and perceived self-efficacy on well-being for each group of participants (with and without LD).

- Gender differences would occur across student groups: girls would report lower social support and lower well-being and higher loneliness than boys, compared to non-LD students.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analyses

3. Results

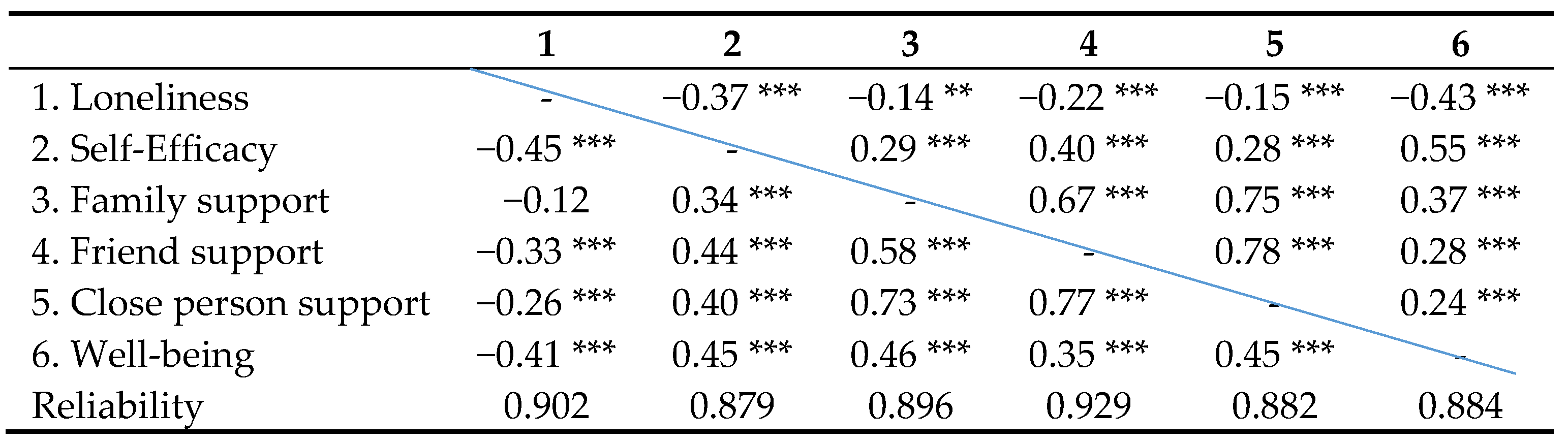

3.1. Preliminary Analysis

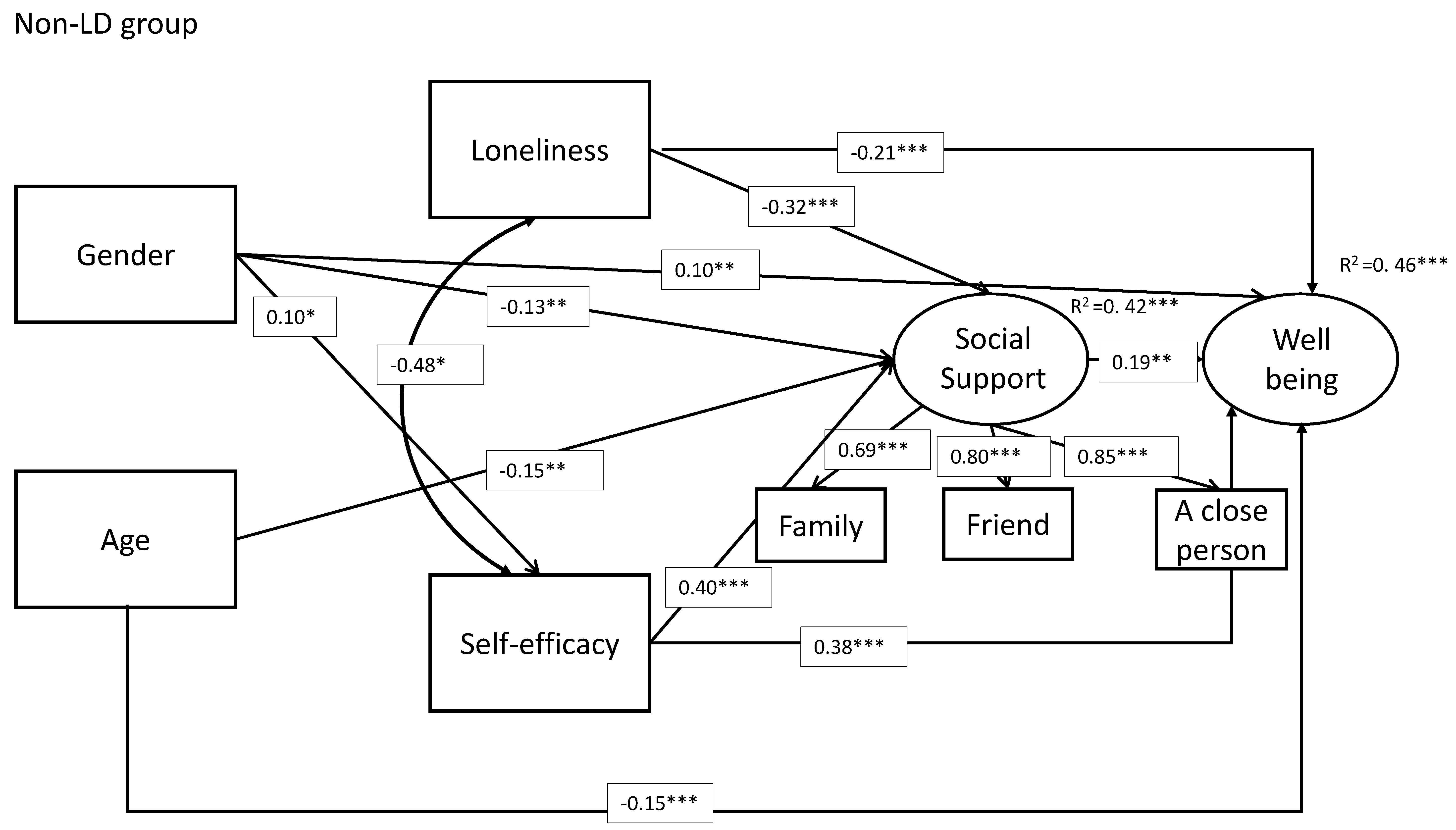

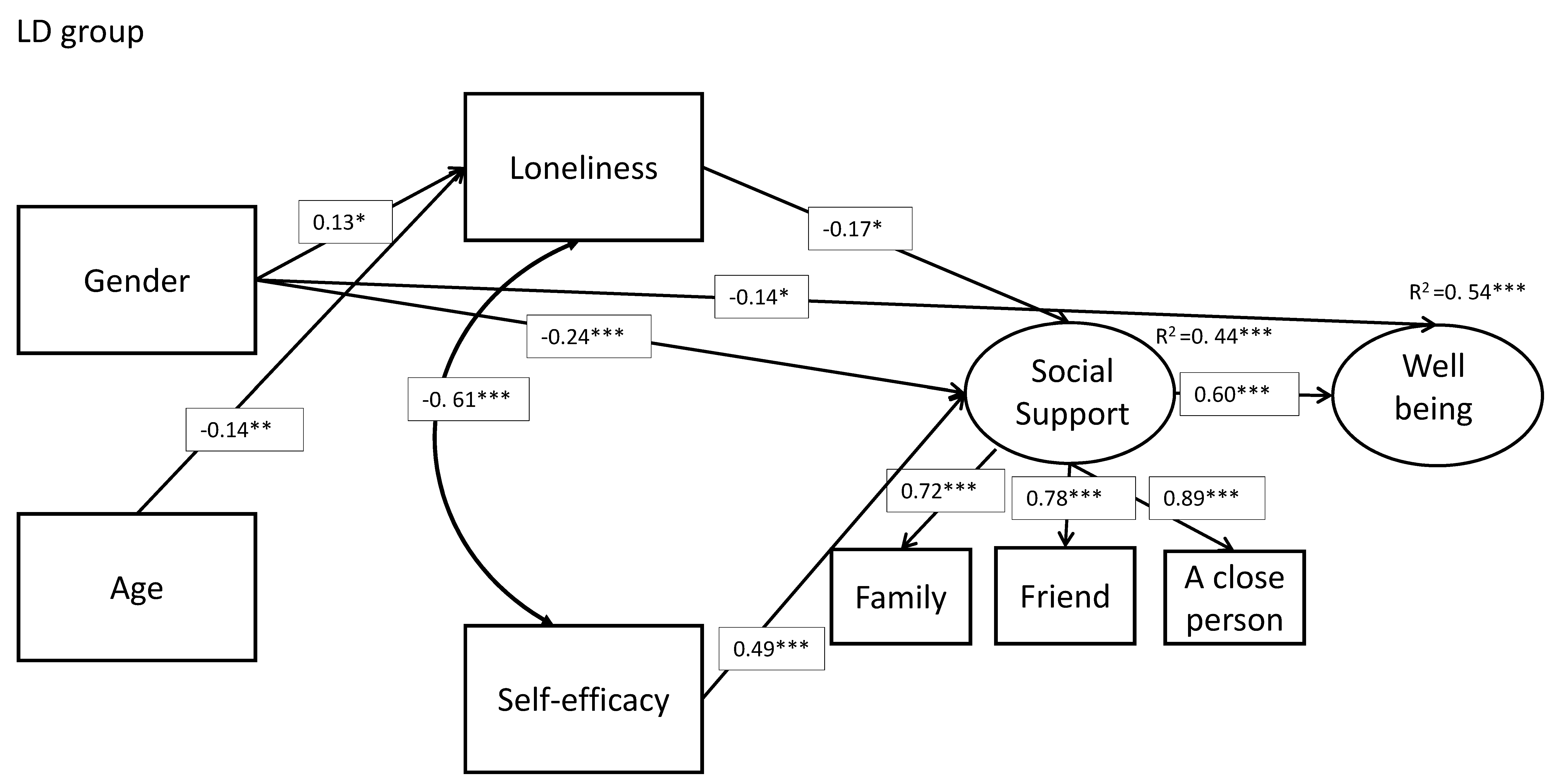

3.2. Modeling Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Future Directions

4.2. Implications for Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wiener, J.; Timmermanis, V. Social relationships of children and youth with learning disabilities. In Learning about Learning Disabilities, 4th ed.; Wong, B.Y.L., Butler, D.L., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 89–140. [Google Scholar]

- Sharabi, A.; Margalit, M. The mediating role of the internet connection, virtual friends, and mood in predicting loneliness among students with and without learning disabilities in different educational environments. J. Learn. Disabil. 2011, 44, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calhoon, M.B.; Berkeley, S.; Scanlon, D. The Erosion of FAPE for students with LD. Learn. Disabil. Res. Pract. 2018, 34, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shecter-Lerner, M.; Lipka, O.; Khouri, M. Attitudes and knowledge about learning disabilities: A comparison between Arabic and Hebrew speaking university students. J. Learn. Disabil. 2019, 52, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demaray, M.K.; Maleck, C.K. The relationship between perceived social support and maladjustment for students at risk. Psychol. Sch. 2002, 39, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, M.G.; Ben-Knaz, R. It’s not academic, you’re in the army now: Adjustment to the army as a comparative context for adjustment to university. J. Adolesc. Res. 2000, 15, 145–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beran, T.N.; Rinaldi, C.; Bickham, D.S.; Rich, M. Evidence of the need to support adolescents dealing with harassment and cyber-harassment: Prevalence, progression, and impact. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2012, 33, 562–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idan, O.; Margalit, M. Socioemotional self-perceptions, family climate, and hopeful thinking among students with learning disabilities and typically achieving students from the same classes. J. Learn. Disabil. 2014, 47, 136–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiman, T.; Olenik-Shemesh, D. Predictors of cyber-victimization of higher-education students with and without learning disabilities. J. Youth Stud. 2018, 22, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, R.J.; Higgins, E.L.; Raskind, M.H.; Herman, K.L. Predictors of success in individuals with learning disabilities: A qualitative analysis of a 20 years’ longitudinal study. Learn. Disabil. Res. Pract. 2003, 18, 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skues, J.L.; Cunningham, E.G.; Theiler, S.S. Examining prediction models of giving up within a resource-based framework of coping in primary school students with and without learning disabilities. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2016, 63, 224–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yagon, M. Socioemotional and behavioral adjustment among school-age children with learning disabilities: The moderating role of maternal personal resources. J. Spec. Educ. 2007, 40, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, S.D.; Lawrence, S.C.; Hunter, S.C. Loneliness accounts for the association between diagnosed attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder and symptoms of depression among adolescents. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2020, 42, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zach, S.; Yadi-Ugav, O.; Zeev, A. Academic achievements, behavioral problems, and loneliness as predictors of social skills among students with and without learning disorders. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2016, 37, 378–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coplan, R.J.; Closson, L.M.; Arbeau, K.A. Gender differences in the behavioral associates of loneliness and social dissatisfaction in kindergarten. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatr. 2007, 48, 988–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosnoe, R.; Riegle-Crumb, C.; Muller, C. Gender, self-perception, and academic problems in high school. Soc. Probl. 2007, 54, 118–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavioni, V.; Grazzani, I.; Ornaghi, V. Social and Emotional Learning for Children with Learning Disability: Implications for Inclusion; Department of Human Sciences for Education, University of Milano-Bicocca: Milan, Italy, 2017; Volume 9, pp. 100–109. [Google Scholar]

- Lijuan, Q.; Rui, Z.; Benxian, Y.A.O.; Xiao, Z. The effect of loneliness and coping style on academic adjustment among college freshmen. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2014, 42, 969–978. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Toward a Psychology of Human Agency: Pathways and Reflections. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 13, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; W.H. Freeman and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.P.; Chan, J. Career guidance for learning-disabled youth. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 2014, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojewski, J.W.; Lee, I.H.; Gregg, N.; Gemici, S. Development patterns of occupational aspirations in adolescents with high-incidence disabilities. Except. Child. 2012, 78, 157–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, R.; Maddux, C.D.; Casey, J. Individualized transition planning for students with learning disabilities. Career Dev. Q. 2000, 49, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haft, S.L.; Myers, C.A.; Hoeft, F. Socio-emotional and cognitive resilience in children with reading disabilities. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2016, 10, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raines, J.C. Improving the self-esteem and social skills of students with learning disabilities. In School Social Work and Mental Health Worker’s Training and Resource Manual, 2nd ed.; Franklin, C., Harris, M.B., Allen-Meares, P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 237–250. [Google Scholar]

- Einav, M.; Sharabi, A.; Even-Hen Peter, T.; Margalit, M. Test accommodations and Positive affect among adolescents with learning disabilities: The mediating role of attitudes, academic self-efficacy, loneliness and hope. Athens J. Educ. 2018, 5, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, N.Z.; Mason, E. Learning disabilities, gender, sources of efficacy, self-efficacy beliefs, and academic achievement in high school students. J. Sch. Psychol. 2003, 41, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a National Index (PDF). Am. Psychol. 2020, 55, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olenik-Shemesh, D.; Heiman, T.; Keshet, S.N. The role of career aspiration, self-esteem, body esteem, and gender in predicting sense of wellbeing among emerging adults. J. Genet. Psychol. 2018, 179, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viner, R.M.; Ozer, E.M.; Denny, S.; Marmot, M. Adolescence and the social determinants of health. Lancet 2012, 379, 1641–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardal, E.; Holsen, I.; Diseth, A.; Larson, T. The Five Cs of positive youth development in a school context: Gender and mediator effects. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2018, 39, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimet, G.D.; Dahlem, M.W.; Zimet, S.G.; Parley, G.K. The multidimensional scale for perceived social support. J. Personal. Assess. 1988, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asher, S.R.; Hymel, S.; Renshaw, P.D. Loneliness in Children. Child Dev. 1984, 55, 1456–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muris, P. A brief questionnaire for measuring self-efficacy in youths. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2001, 23, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 95, 542–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, R.; Larsen, J.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Hefetz, A.; Liberman, G. Applying Structural Equation Modeling in Educational Research. Cult. Educ. 2017, 29, 563–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural equation modeling: Perspectives on the present and the future. Int. J. Test. 2001, 1, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiman, T.; Olenik-Shemesh, D. Cyberbullying experience among adolescents with LD attending general and special education classes. J. Learn. Disabil. 2015, 48, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, R.S. Social support in inclusive middle schools: Perceptions of youth with learning disabilities. Psychol. Sch. 2006, 43, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavri, S.; Monda-Amaya, L. Social support in inclusive schools: Student and teacher perspectives. Except. Child. 2001, 67, 391–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, G.L.; Scott, W.D.; Dearing, E.; Hamill, S.K. Cognitive self-regulation in youth with and without learning disabilities: Academic self-efficacy, theories of intelligence, learning vs. performance goal preferences, and effort attributions. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 28, 881–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharfi, K.; Rosenblum, S. Sensory modulation and sleep quality among adults with learning disabilities: A quasi-experimental case-control design study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0115518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel-Yager, B.; Muzio, C.; Rinosi, G.; Solano, P.; Geoffroy, P.A.; Pompili, M.; Amore, M.; Serafini, G. Extreme sensory processing patterns and their relation with clinical conditions among individuals with major affective disorders. Psychiatr. Res. 2016, 236, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Non-LD Group (n = 587) | LD Group (n = 247) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | F(1832) | η2p | |

| Loneliness | 27.71 | 11.87 | 28.26 | 12.27 | 0.37 | 0.00 |

| Self-efficacy | 3.72 | 0.77 | 3.58 | 0.82 | 5.18 * | 0.006 |

| Family support | 5.81 | 1.91 | 5.91 | 1.69 | 0.58 | 0.001 |

| Friend support | 5.30 | 2.05 | 5.37 | 1.97 | 0.21 | 0.00 |

| Close person support | 5.70 | 1.91 | 5.75 | 1.81 | 0.10 | 0.00 |

| Well-being | 5.61 | 1.31 | 5.36 | 1.48 | 5.83 * | 0.007 |

| Fit Parameter | χ2(df), p | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | |||||

| One Model | 11.75(6), 0.068 | 0.998 | 0.995 | 0.034 | 0.009 |

| M1: Configured | 26.72(12), 0.009 | 0.995 | 0.987 | 0.054 | 0.014 |

| M2: Metric | 36.64(16), 0.001 | 0.992 | 0.984 | 0.060 | 0.037 |

| M3: Scalar | 40.36(20), 0.005 | 0.993 | 0.989 | 0.049 | 0.039 |

| ∆M2-M1 | 12.92(4), 0.012 | 0.003 | |||

| ∆M3-M1 | 13.64(8), 0.092 | 0.002 | |||

| ∆M3-M2 | 0.72(4), 0.095 | 0.001 |

| Loneliness | Self-Efficacy | Support | Well-Being | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-LD group | ||||

| Gender | 0.47 (0.94) | 0.15 * (0.06) | −0.33 ** (0.11) | 0.27 ** (0.09) |

| Age | 0.03 (0.24) | −0.01 (0.2) | 0.09 ** (0.03) | −0.10 *** (0.02) |

| Loneliness | −0.04 *** (0.01) | −0.03 *** (0.01) | ||

| Self-efficacy | 0.72 *** (0.12) | 0.72 *** (0.10) | ||

| Social support | 0.20 ** (0.06) | |||

| R2 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.41 *** (0.05) | 0.46 *** (0.04) |

| LD group | ||||

| Gender | 3.08 * (1.42) | −0.01 (0.10) | −0.65 *** (0.16) | 0.41 * (0.19) |

| Age | −0.75 * (0.34) | −0.01 (0.02) | 0.05 (0.04) | −0.06 (0.04) |

| Loneliness | −0.02 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | ||

| Self-efficacy | 0.85 *** (0.18) | 0.27 (0.20) | ||

| Social support | 0.67 *** (0.14) | |||

| R2 | 0.04 * (0.02) | 0.001 (0.01) | 0.45 *** (0.06) | 0.54 *** (0.06) |

| Independent | Mediator | Dependent | Independent → Mediator | Mediator → Dependent | Independent → Dependent | Indirect Effect | 95% CI Indirect Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-LD group | |||||||

| Age | Social support | Well-being | 0.09 ** (0.03) | 0.20 ** (0.06) | −0.10 *** (0.02) | 0.02 * (0.01) | [0.01, 0.03] |

| Loneliness | Social support | Well-being | −0.04 *** (0.01) | 0.20 ** (0.06) | −0.03 *** (0.01) | −0.007 ** (0.003) | [−0.01, −0.003] |

| Self-efficacy | Social support | Well-being | 0.72 *** (0.12) | 0.20 ** (0.06) | 0.72 *** (0.10) | 0.14 * (0.06) | [0.06, 0.28] |

| Gender | Self- efficacy | Well-being | 0.15 * (0.06) | 0.72 *** (0.10) | 0.27 ** (0.09) | 0.11 * (0.04) | [0.03, 0.20] |

| Gender | Social support | Well-being | −0.33 ** (0.11) | 0.20 ** (0.06) | 0.27 ** (0.09) | −0.06 * (0.03) | [−0.14, −0.02] |

| LD group | |||||||

| Self-efficacy | Social support | Well-being | 0.85 *** (0.18) | 0.67 *** (0.14) | 0.27 (0.20) | 0.56 *** (0.15) | [0.32, 0.88] |

| Gender | Social support | Well-being | −0.65 *** (0.16) | 0.67 *** (0.14) | −0.43 ** (0.14) | −0.43 ** (0.14) | [−0.73, −0.19] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Heiman, T.; Olenik-Shemesh, D. Social-Emotional Profile of Children with and without Learning Disabilities: The Relationships with Perceived Loneliness, Self-Efficacy and Well-Being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7358. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207358

Heiman T, Olenik-Shemesh D. Social-Emotional Profile of Children with and without Learning Disabilities: The Relationships with Perceived Loneliness, Self-Efficacy and Well-Being. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(20):7358. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207358

Chicago/Turabian StyleHeiman, Tali, and Dorit Olenik-Shemesh. 2020. "Social-Emotional Profile of Children with and without Learning Disabilities: The Relationships with Perceived Loneliness, Self-Efficacy and Well-Being" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 20: 7358. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207358

APA StyleHeiman, T., & Olenik-Shemesh, D. (2020). Social-Emotional Profile of Children with and without Learning Disabilities: The Relationships with Perceived Loneliness, Self-Efficacy and Well-Being. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(20), 7358. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207358