What Is Rural Adversity, How Does It Affect Wellbeing and What Are the Implications for Action?

Abstract

1. Introduction

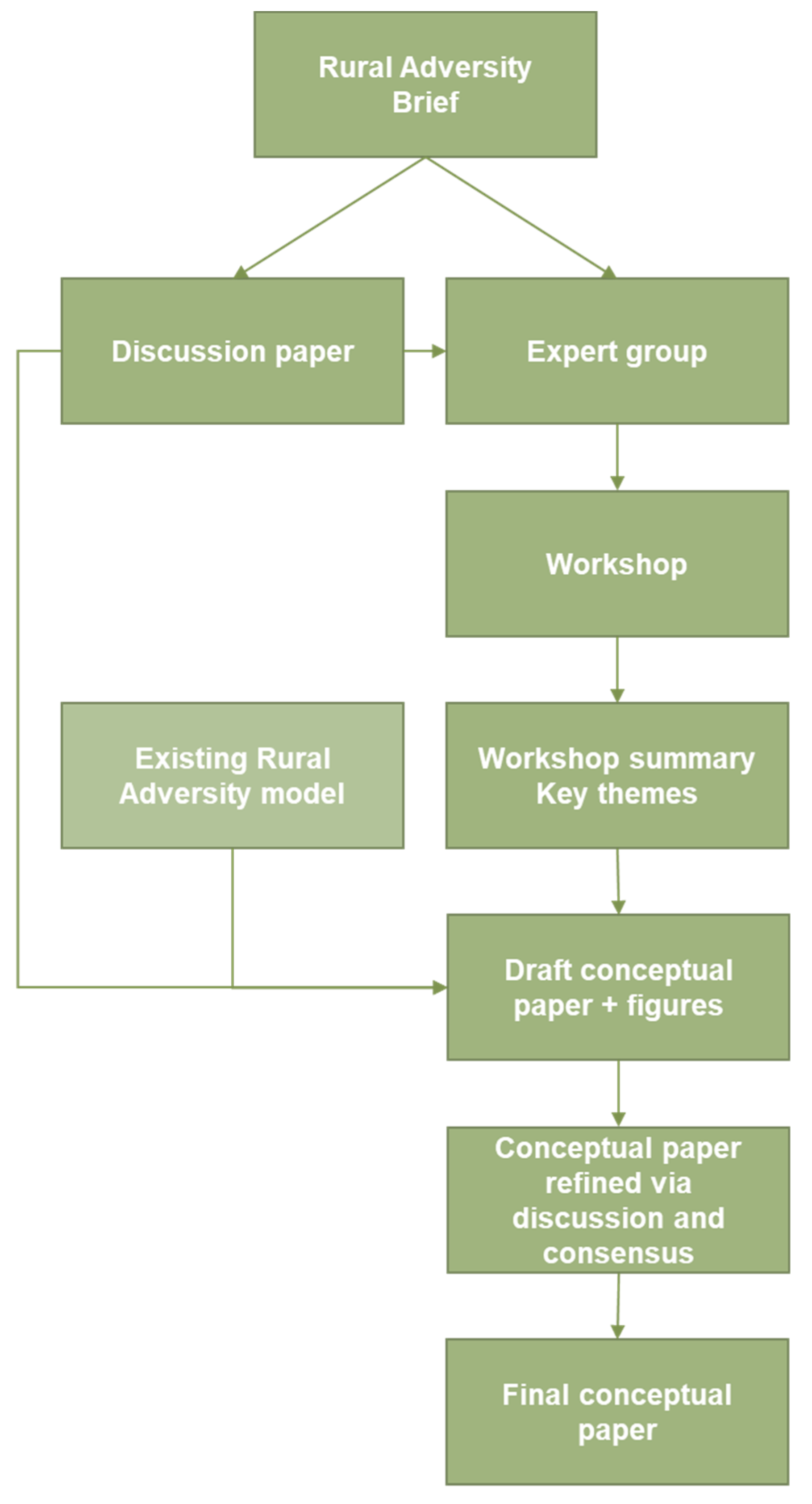

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Workshop—Rethinking and Reframing Rural Adversity

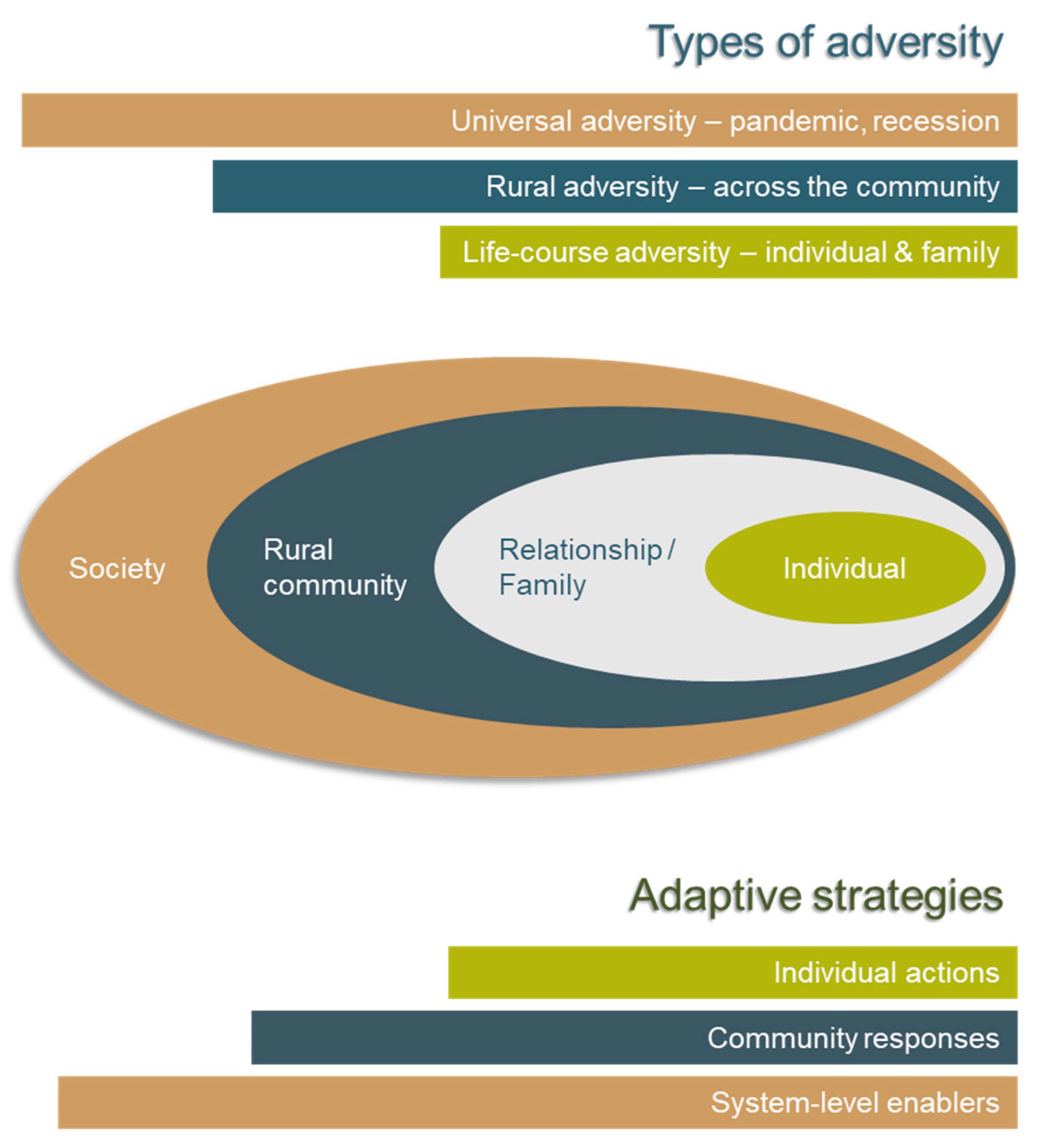

3.2. How can we Explore Rural Diversity?

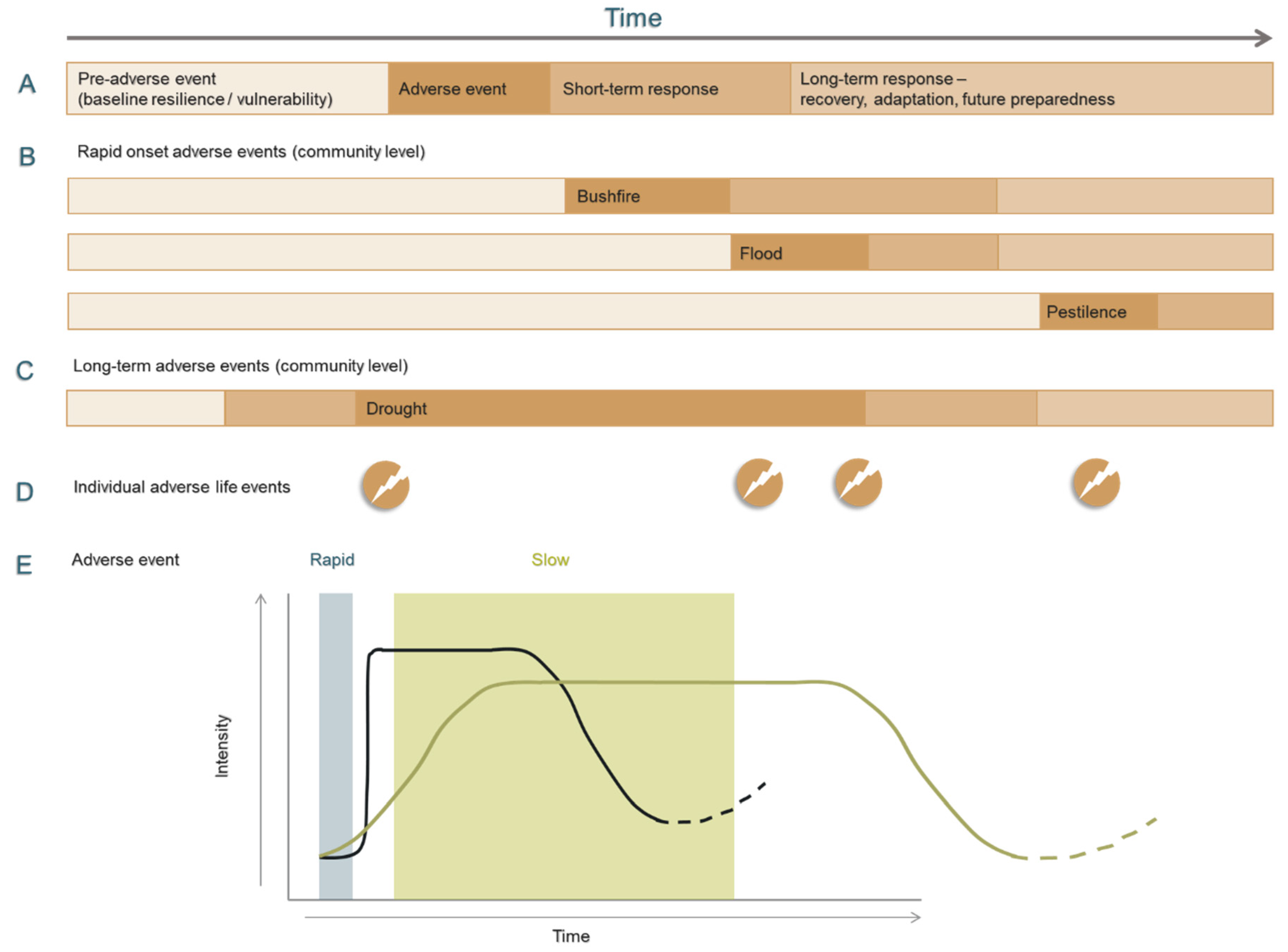

3.3. What does Adversity Look Like from a Rural Perspective?

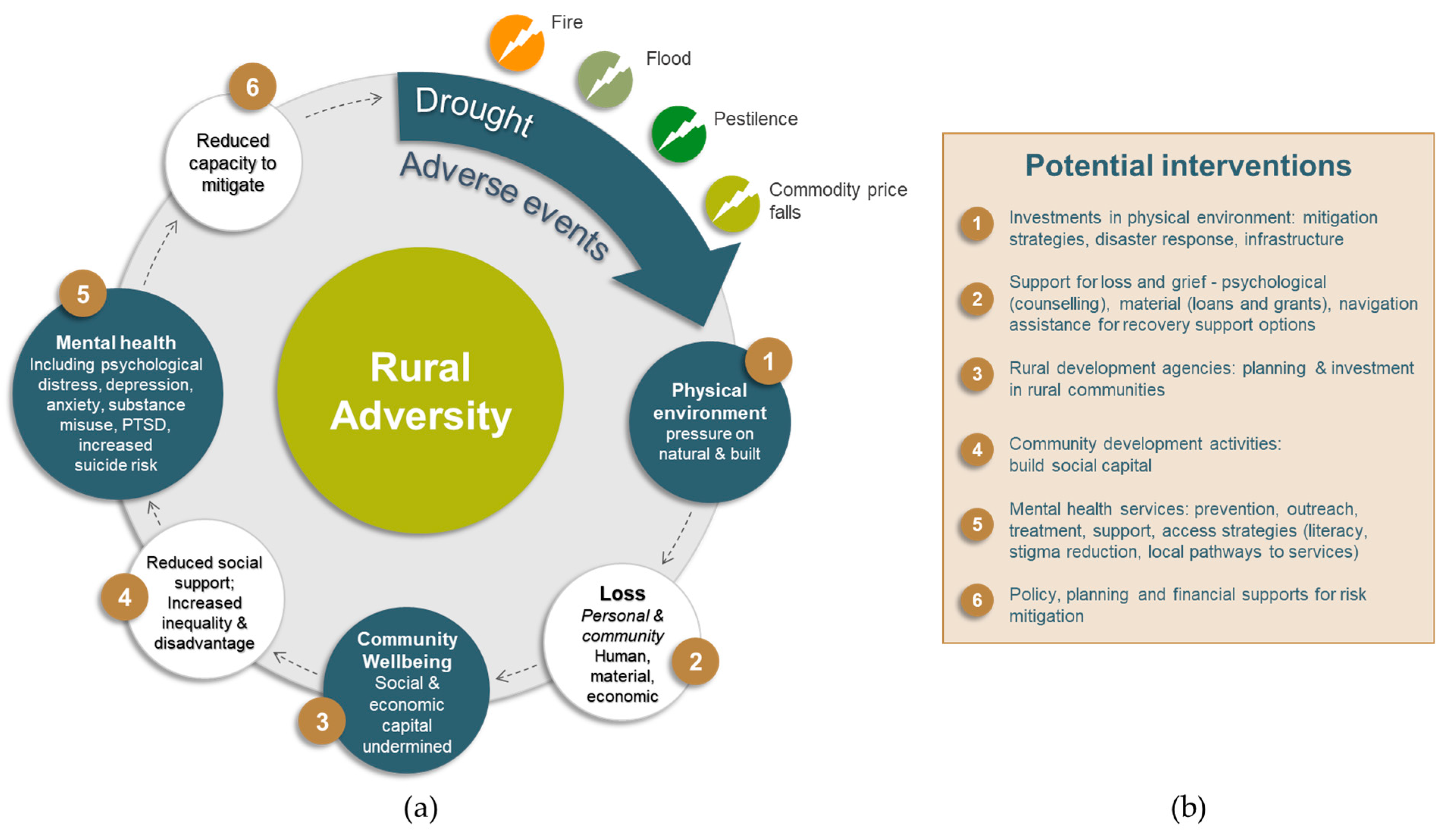

3.4. How does Rural Adversity Impact on Wellbeing and What Are the Opportunities for Interventions?

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bourke, L.; Humphreys, J.S.; Wakerman, J.; Taylor, J. Charting the future course of rural health and remote health in Australia: Why we need theory. Aust. J. Rural. Heal. 2010, 18, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, B.; Lewin, T.J.; Stain, H.; Coleman, C.; Fitzgerald, M.; Perkins, D.; Carr, V.J.; Fragar, L.; Fuller, J.; Lyle, D.; et al. Determinants of mental health and well-being within rural and remote communities. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2010, 46, 1331–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health: Strengthening our Response. Fact Sheet. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs220/en/ (accessed on 12 November 2019).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s Health; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, J.; Edwards, J.; Procter, N.; Moss, J. How definition of mental health problems can influence help seeking in rural and remote communities. Aust. J. Rural. Heal. 2000, 8, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farmer, J.; Clark, A.; Munoz, S.-A. Is a global rural and remote health research agenda desirable or is context supreme? Aust. J. Rural Health 2010, 18, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourke, L.; Humphreys, J.S.; Wakerman, J.; Taylor, J. Understanding drivers of rural and remote health outcomes: A conceptual framework in action. Aust. J. Rural Health 2012, 20, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, D.; Farmer, J.; Salvador-Carulla, L.; Dalton, H.E.; Luscombe, G. The Orange Declaration on rural and remote mental health. Aust. J. Rural Health 2019, 27, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, D.; Cross, S.P. Regional planning for meaningful person-centred care in mental health: Context is the signal not the noise. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2020, 29, e104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, J. Changing how we think about healthcare improvement. BMJ 2018, 361, k2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, J.; Clay-Williams, R.; Nugus, P.; Plumb, J. Health care as a complex adaptive system. In Resilient Health Care; Hollnagel, E., Braithwaite, J., Wears, R.L., Eds.; Ashgate Publishing: Farnham, Surrey, UK, 2013; pp. 57–73, (Ashgate Studies in Resilience Engineering). [Google Scholar]

- Furst, M.A.; Bagheri, N.; Salvador-Carulla, L. An ecosystems approach to mental health services research. BJPsych. Int. 2020, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, S.; Curtis, S.; Diez-Roux, A.V.; MacIntyre, S. Understanding and representing ‘place’ in health research: A relational approach. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 65, 1825–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D. For Space; SAGE publishing: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer, J.; Munoz, S.-A.; Threlkeld, G. Theory in rural health. Aust. J. Rural Health 2012, 20, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, C.R.; Berry, H.L.; Tonna, A.M. Improving the mental health of rural New South Wales communities facing drought and other adversities. Aust. J. Rural Health 2011, 19, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, R. Writing narrative style literature reviews. Med. Writ. 2015, 24, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola, E. Designing conceptual articles: Four approaches. AMS Rev. 2020, 10, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankivsky, O. Women’s health, men’s health, and gender and health: Implications of intersectionality. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 1712–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankivsky, O.; Grace, D.; Hunting, G.; Giesbrecht, M.; Fridkin, A.; Rudrum, S.; Ferlatte, O.; Clark, N. An intersectionality-based policy analysis framework: Critical reflections on a methodology for advancing equity. Int. J. Equity Health 2014, 13, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vins, H.; Bell, J.; Saha, S.; Hess, J.J. The Mental Health Outcomes of Drought: A Systematic Review and Causal Process Diagram. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 13251–13275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, W.L. The Angry Summer; Climate Commission Secretariat: Canberra, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stain, H.; Kelly, B.; Lewin, T.J.; Higginbotham, N.; Beard, J.R.; Hourihan, F. Social networks and mental health among a farming population. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2008, 43, 843–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigby, C.W.; Rosen, A.; Berry, H.L.; Hart, C.R. If the land’s sick, we’re sick: The impact of prolonged drought on the social and emotional well-being of Aboriginal communities in rural New South Wales. Aust. J. Rural Health 2011, 19, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimer, H. Topophilia and Quality of Life: Defining the Ultimate Restorative Environment. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005, 113, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, N.; Adger, W.N.; Agnolucci, P.; Blackstock, J.; Byass, P.; Cai, W.; Chaytor, S.; Colbourn, T.; Collins, M.; Cooper, A.; et al. Health and climate change: Policy responses to protect public health. Lancet 2015, 386, 1861–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stain, H.J.; Kelly, B.; Carr, V.J.; Lewin, T.J.; Fitzgerald, M.; Fragar, L. The psychological impact of chronic environmental adversity: Responding to prolonged drought. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 73, 1593–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogan, R.; O’Connor, M.; Horwitz, P. Nowhere to hide: Awareness and perceptions of environmental change, and their influence on relationships with place. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, G.; Sartore, G.-M.; Connor, L.; Higginbotham, N.; Freeman, S.; Kelly, B.; Stain, H.; Tonna, A.; Pollard, G. Solastalgia: The Distress Caused by Environmental Change. Australas. Psychiatry 2007, 15, S95–S98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosgrave, C. Context Matters: Findings from a Qualitative Study Exploring Service and Place Factors Influencing the Recruitment and Retention of Allied Health Professionals in Rural Australian Public Health Services. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragar, L.; Henderson, A.; Morton, C.; Pollock, K. The Mental Health of People on Australian Farms: The Facts 2008; Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation and Australian Centre for Agricultural Health and Safety: Moree, NSW, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, C.; Jackson, H.J.; Judd, F.; Komiti, A.; Robins, G.; Murray, G.; Humphreys, J.; Pattison, E.P.; Hodgins, G. Changing places: The impact of rural restructuring on mental health in Australia. Health Place 2005, 11, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragar, L.; Stain, H.; Perkins, D.; Kelly, B.; Fuller, J.; Coleman, C.; Lewin, T.J.; Wilson, J.M. Distress among rural residents: Does employment and occupation make a difference? Aust. J. Rural Health 2010, 18, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askland, H.H. A dying village: Mining and the experiential condition of displacement. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2018, 5, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2071.0—Census of Population and Housing: Reflecting Australia—Stories from the Census, 2016, 2017. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/2071.0~2016~Main%20Features~Ageing%20Population~14 (accessed on 16 March 2020).

- Holmes, J.; Argent, N. Rural transitions in the Nambucca Valley: Socio-Demographic change in a disadvantaged rural locale. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 48, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Report for the Minister for Regional Health, Regional Communications and Local Government on the Improvement of Access, Quality and Distribution of Allied Health Services in Regional, Rural and Remote Australia; Australian Government (N.R.H.C.): Canberra, Australia, 2020.

- Dummer, T.J. Health geography: Supporting public health policy and planning. Can. Med Assoc. J. 2008, 178, 1177–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, N.; Benwell, G.L.; Holt, A. Primary Health Care Accessibility for Rural Otago:’A Spatial Analysis’. In HIC 2006 and HINZ 2006: Proceedings; Health Informatics Society of Australia: Brunswick East, Australia, 2006; p. 365. [Google Scholar]

- Bagheri, N.; Batterham, P.J.; Salvador-Carulla, L.; Chen, Y.; Page, A.; Calear, A.L.; Congdon, P. Development of the Australian neighborhood social fragmentation index and its association with spatial variation in depression across communities. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2019, 54, 1189–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvador-Carulla, L.; Amaddeo, F.; Gutierrez-Colosia, M.R.; Salazzari, D.; Gonzalez-Caballero, J.-L.; Montagni, I.; Tedeschi, F.; Cetrano, G.; Chevreul, K.; Kalseth, J.; et al. Developing a tool for mapping adult mental health care provision in Europe: The REMAST research protocol and its contribution to better integrated care. Int. J. Integr. Care 2015, 15, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iruin-Sanz, A.; Pereira-Rodríguez, C.; Nuño-Solinis, R. The role of geographic context on mental health: Lessons from the implementation of mental health atlases in the Basque Country (Spain). Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2014, 24, 42–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeniemi, M.; Almeda, N.; Salinas-Pérez, J.A.; Gutierrez-Colosia, M.R.; García-Alonso, C.R.; Ala-Nikkola, T.; Joffe, G.; Pirkola, S.; Wahlbeck, K.; Cid, J.; et al. A Comparison of Mental Health Care Systems in Northern and Southern Europe: A Service Mapping Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, Y.; Salvador-Carulla, L.; Salinas-Pérez, J.A.; Uriarte-Uriarte, J.J.; Iruin-Sanz, A.; García-Alonso, C.R. Use of the self-organising map network (SOMNet) as a decision support system for regional mental health planning. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2018, 16, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Spijker, A.B.; Salinas-Pérez, J.A.; Mendoza, J.; Bell, T.; Bagheri, N.; Furst, M.A.; Reynolds, J.; Rock, D.; Harvey, A.; Rosen, A.; et al. Service availability and capacity in rural mental health in Australia: Analysing gaps using an Integrated Mental Health Atlas. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2019, 53, 1000–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, S.J.; Perkins, D.; Luland, T.; Brown, D.; Corvan, E. The effect of context in rural mental health care: Understanding integrated services in a small town. Health Place 2017, 45, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.M.; Penrod, J. Linking concepts of enduring, uncertainty, suffering, and hope. Image J. Nurs. Sch. 1999, 31, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malilay, J.; Heumann, M.; Perrotta, D.; Wolkin, A.F.; Schnall, A.H.; Podgornik, M.N.; Cruz, M.A.; Horney, J.A.; Zane, D.; Roisman, R.; et al. The Role of Applied Epidemiology Methods in the Disaster Management Cycle. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 2092–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrira, A.; Litwin, H. The Effect of Lifetime Cumulative Adversity and Depressive Symptoms on Functional Status. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2014, 69, 953–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, S. Conceptualizing and Identifying Cumulative Adversity and Protective Resources: Implications for Understanding Health Inequalities. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2005, 60, S130–S134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dorn, A.; Cooney, E.R.; Sabin, M.L. COVID-19 exacerbating inequalities in the US. Lancet 2020, 395, 1243–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, T. Health, human development and the community ecosystem: Three ecological models. Health Promot. Int. 1993, 8, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, M.; Reeves, A.; Clair, A.; Stuckler, D. Living on the edge: Precariousness and why it matters for health. Arch. Public Health 2017, 75, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashby, W.R.; Goldstein, J. Variety, Constraint, and the Law of Requisite Variety. Emerg. Complex Organ. 2011, 13, 190–207. [Google Scholar]

- Boyko, J.A.; Lavis, J.; Abelson, J.; Dobbins, M.; Carter, N. Deliberative dialogues as a mechanism for knowledge translation and exchange in health systems decision-making. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 1938–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwacha, V. Canada’s Experience in Developing a National Disaster Mitigation Strategy: A Deliberative Dialogue Approach. Mitig. Nat. Hazards Disasters Int. Perspect. 2006, 10, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, D.Y.T.; Spittal, M.J.; Pirkis, J.; Yip, P.S.F. Spatial analysis of suicide mortality in Australia: Investigation of metropolitan-rural-remote differentials of suicide risk across states/territories. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 1460–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Initial Submission to the Productivity Commission Inquiry into Mental Health; Australian Government Department of Health: Canberra, Australia, 2019.

| Workshop Themes | Rethinking and Reframing Rural Adversity |

|---|---|

| Rural resident centred | Moving from fragmented and segmented views to a holistic approach with rural people at the centre Considering how policy for an average person in an average place can be translated into local, contextually relevant responses for real people that recognises individual diversity within complex multi-layered social contexts |

| Rural diversity | A contextual view of rural variation rather than simple urban/rural comparisons; understanding place as a key variable |

| Rural adversity | Moving beyond discrete disaster responses to the inclusion of spatial, scaled, temporal, cumulative, and contextual impacts |

| Ecosystems approach to mental health | Adopting robust and sustainable complex adaptive systems rather than focussing on the efficiency of individual sub-systems Recognising the value of informal supports and support networks at individual, family, community and systems levels |

| Data and methods | Recognising the limitations of current information and evidence and adopting new ways of visualising data in contextually relevant forms Using new insights and methods to guide implementation processes—using evidence to support decision-making Empowering rural people to lead and guide responses to rural adversity |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lawrence-Bourne, J.; Dalton, H.; Perkins, D.; Farmer, J.; Luscombe, G.; Oelke, N.; Bagheri, N. What Is Rural Adversity, How Does It Affect Wellbeing and What Are the Implications for Action? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7205. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197205

Lawrence-Bourne J, Dalton H, Perkins D, Farmer J, Luscombe G, Oelke N, Bagheri N. What Is Rural Adversity, How Does It Affect Wellbeing and What Are the Implications for Action? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(19):7205. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197205

Chicago/Turabian StyleLawrence-Bourne, Joanne, Hazel Dalton, David Perkins, Jane Farmer, Georgina Luscombe, Nelly Oelke, and Nasser Bagheri. 2020. "What Is Rural Adversity, How Does It Affect Wellbeing and What Are the Implications for Action?" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 19: 7205. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197205

APA StyleLawrence-Bourne, J., Dalton, H., Perkins, D., Farmer, J., Luscombe, G., Oelke, N., & Bagheri, N. (2020). What Is Rural Adversity, How Does It Affect Wellbeing and What Are the Implications for Action? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(19), 7205. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197205