Customer Restaurant Choice: An Empirical Analysis of Restaurant Types and Eating-Out Occasions

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The first objective was to rank the factors that are important for the selection of restaurants (i.e., (a) word-of-mouth recommendations from people I know, (b) online reviews from customers, (c) brand reputation, (d) brand popularity, (e) personal or past experience with the restaurant, (f) variety of menu items, (g) menu price, (h) sales promotion, and (i) location).

- The second objective was to uncover the order of importance among the factors for customers to consider when choosing a restaurant by eating-out occasions ((a) quick meal/convenience, (b) social occasion, (c) business necessity, and (d) celebration).

- The third objective was to identify the relative importance among the restaurant selection factors by restaurant types ((a) full-service restaurants, (b) quick-casual/convenience restaurants, and (c) quick-service restaurants).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Critical Restaurant Selection Factors

2.1.1. Word-of-Mouth Recommendations from People I Know

2.1.2. Online Review from Customers

2.1.3. Brand Reputation of Restaurant

2.1.4. Brand Popularity

2.1.5. Personal or Past Experience with a Restaurant

2.1.6. Variety of Menu Items

2.1.7. Menu Price

2.1.8. Sales Promotion

2.1.9. Location

2.2. Eating-out Occasions (Quick Meal/Convenience, Social Occasion, Business Necessity, and Celebration) and Customer Behaviors

2.3. Restaurant Types (Full-Service, Quick-Casual, and Quick-Service) and Customer Behaviors

3. Methodology

3.1. Measures

3.2. Sample and Data Collection

- Do you regularly eat-out at restaurants on weekends?

- What is your age?

- Are you currently employed/working?

4. Results

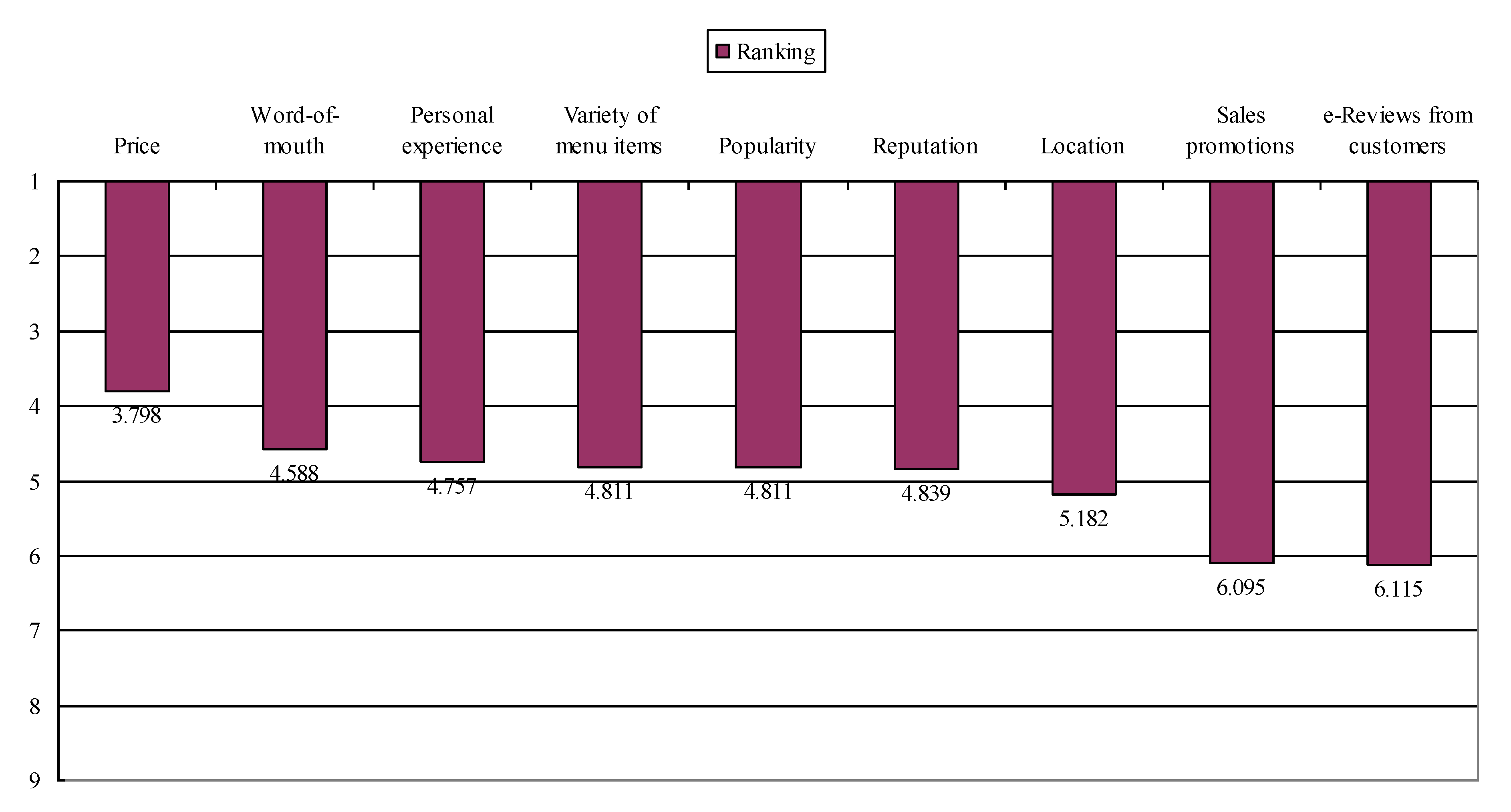

4.1. General Order of Importance for Restaurant Choice

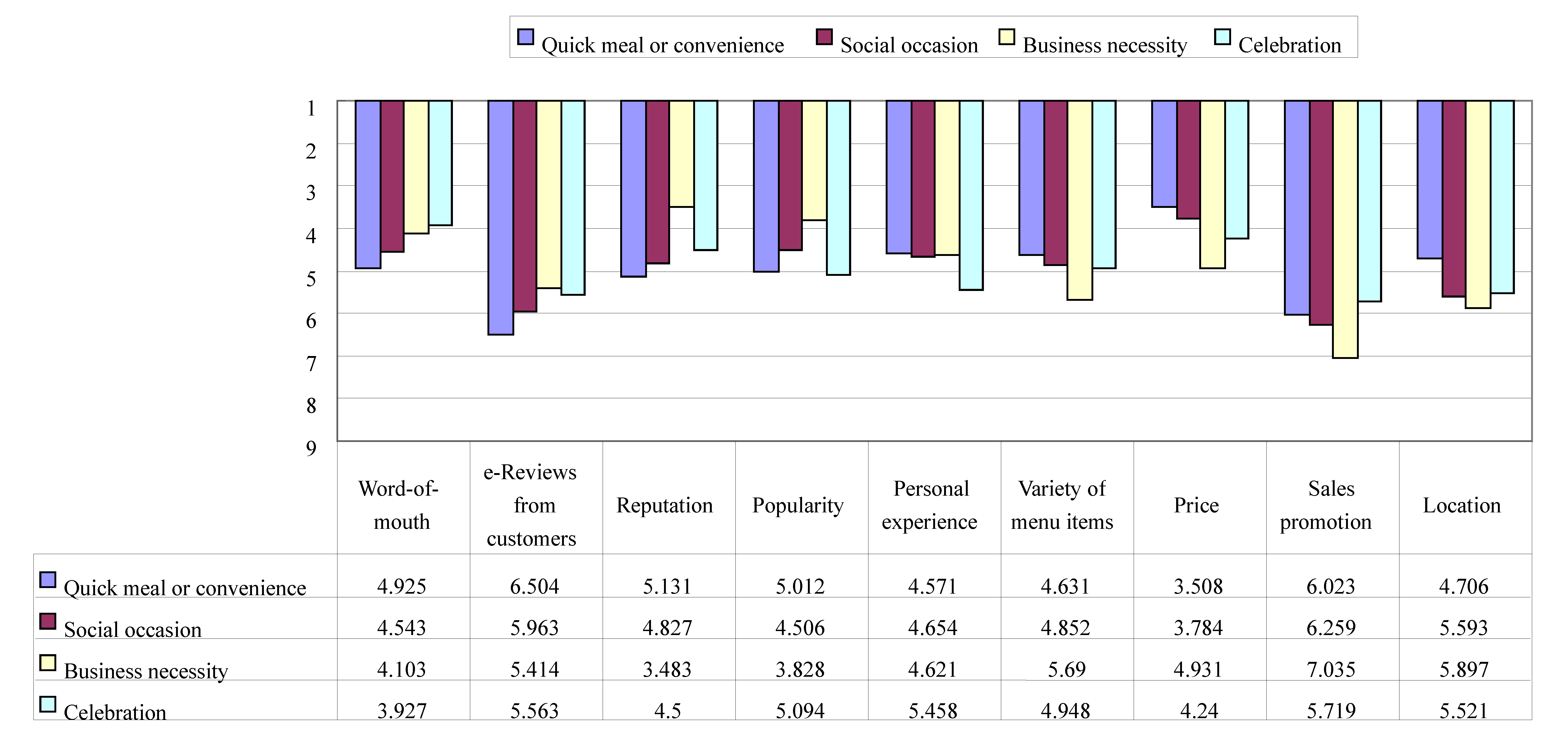

4.2. Ranking by Eating-out Occasions

4.3. Ranking by Restaurant Types

5. Discussion

6. Implications

7. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hwang, J.; Cho, S.; Kim, W. Consequences of psychological benefits of using eco-friendly services in the context of drone food delivery services. J. Trav. Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, H.; Chatzopoulou, E.; Gorton, M. Perceptions of localness and authenticity regarding restaurant choice in tourism settings. J. Trav. Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.; Jang, S.C. Attributes, consequences, and consumer values: A means-end chain approach across restaurant segments. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 25, 383–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scozzafava, G.; Contini, C.; Romano, C.; Casini, L. Eating out: Which restaurant to choose? Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 1870–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiPietro, R. Restaurant and foodservice research: A critical reflection behind and an optimistic look ahead. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 1203–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Norton, D.P. The Strategy-Focused Organization; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, D.; Biel, D. Incorporating satisfaction measures into a restaurant productivity index. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 26, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedraja, M.; Yagüe, J. What information do customers use when choosing a restaurant? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2001, 13, 316–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mothersbaugh, D.L.; Hawkins, D.I. Consumer Behavior: Building Marketing Strategy, 13th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, N.H. Integration theory and attitude change. Psychol. Rev. 1971, 78, 171–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, P.H.; Richins, M.L. A theoretical model for the study of product importance perceptions. J. Mark. 1983, 47, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, J. A strategy for enhancing senior tourists’ well-being perception: Focusing on the experience economy. J. Trav. Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teas, R.K. Expectations, performance evaluation, and consumers’ perceptions of quality. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heide, M.; Grønhaug, K. Key factors in guests’ perception of hotel atmosphere. Cornell Hosp. Quart. 2009, 50, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Kerstetter, D.L.; Mattila, A.S. The attributes of a cruise ship that influence the decision making of cruisers and potential cruisers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, J.; Dearden, P.; Rollins, R. But are tourists satisfied? Importance-performance analysis of the whale shark tourism industry on Isla Holbox, Mexico. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 692–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiciudean, G.O.; Harun, R.; Muresan, I.C.; Arion, F.H.; Chiciudean, D.I.; Ilies, G.L.; Dumitras, D.E. Assessing the importance of health in choosing a restaurant: An empirical study from Romania. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cullen, F. Factors influencing restaurant selection in Dublin. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2004, 7, 53–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, R.J.; Ottenbacher, M.C.; Kendall, K.W. Fine-dining restaurant selection: Direct and moderating effects of customer attributes. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2011, 14, 272–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, R.J.; Ottenbacher, M.C.; Way, K.A. QSR choice: Key restaurant attributes and the roles of gender, age and dining frequency. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2013, 14, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, C.O.; Salay, E. A review of food service selection factors important to the consumer. Food Public Health 2013, 3, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A.D.; O’Neill, M.; Liu, Y.; O’Shea, M. Factors driving consumer restaurant choice: An exploratory study from the Southeastern United States. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2013, 22, 547–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Zhao, J. Factors influencing restaurant selection in South Florida: Is health issue one of the factors influencing consumers’ behavior when selecting a restaurant? J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2010, 13, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.H.; Tran, B.X.; Thi Nguyen, H.L.; Le, H.T.; Do, H.T.; Kim Dang, A.; Nguyen, C.T.; Latkin, C.A.; Zhang, M.W.B.; Ho, R.C.M. Socio-economic disparities in attitude and preference for menu labels among Vietnamese restaurant customers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponnam, A.; Balaji, M.S. Matching visitation-motives and restaurant attributes in casual dining restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 37, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, N.; Pine, R. Consumer behavior in the food service industry: A review. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2002, 21, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, N.; Lee, S.; Huffman, L. Impact of restaurant experience on brand image and customer loyalty: Moderating role of dining motivation. J. Trav. Tour. Mark. 2012, 29, 532–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, J.A. Role of product-related conversations in the diffusion of a new product. J. Mark. Res. 1967, 4, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S.B. The role of attention in mediating the effect of advertising on attribute importance. J. Cons. Res. 1986, 13, 174–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martilla, J.A.; James, J.C. Importance-performance analysis. J. Mark. 1977, 41, 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettman, J.R.; Luce, M.F.; Payne, J.W. Constructive consumer choice processes. J. Cons. Res. 1998, 25, 187–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsa, H.G.; Self, J.T.; Njite, D.; King, T. Why restaurants fail. Cornell Hotel Rest. Admin. Quart. 2005, 46, 304–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison-Walker, L.J. The measurement of word-of-mouth communication and an investigation of service quality and customer commitment as potential antecedents. J. Serv. Res. 2001, 4, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, E.H.; Jang, S.C. Restaurant experiences triggering positive electronic word of-mouth (eWOM) motivations. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, K.D.; Bateson, J.E.G. Services Marketing: Concepts, Strategies & Cases, 5th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, K.B. A test of services marketing theory: Consumer information acquisition activities. J. Mark. 1991, 55, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaram, D.S.; Mitra, K.; Webster, C. Word-of-mouth communications: A motivational analysis. In NA—Advances in Consumer Research; Alba, J.W., Hutchinson, J.W., Eds.; Association for Consumer Research: Provo, UT, USA, 1998; Volume 25, pp. 527–531. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes, D.; Lomax, W. Taking control of word-of-mouth marketing: The case of an entrepreneurial hotelier. J. Small Bus. Ent. Dev. 2002, 9, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ye, Q.; Law, R.; Li, Y. The impact of e-word-of-mouth on the online popularity of restaurants: A comparison of consumer reviews and editor reviews. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 694–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, B.A.; Browning, V. The impact of online reviews on hotel booking intentions and perception of trust. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1310–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.H.; Lee, J.; Han, J. The effect of online consumer reviews on consumer purchasing intention: The moderating role of involvement. Int. J. Elect. Comm. 2007, 11, 125–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozinets, R. E-tribalized marketing? the strategic implications of virtual communities of consumption. Eur. Manag. J. 1999, 17, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xie, J. Online consumer review: Word-of-mouth as a new element of the marketing communication mix. Manag. Sci. 2008, 54, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.U.; Kim, W.J.; Park, S.C. Consumer perceptions on web advertisements and motivation factors to purchase in the online shopping. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 1208–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarn, D.D.C. Marketing-based tangibilization for services. Serv. Ind. J. 2005, 26, 747–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Gretzel, U. Role of social media in online travel information search. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Law, R.; Gu, B. The impact of online user reviews on hotel room sales. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 180–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellarocas, C. Reputation mechanisms. In Handbook on Information Systems and Economics; Hendershott, T., Ed.; Elsevier Publishing: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 629–660. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, G. Creating Corporate Reputations; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, C.; Thomsen, S. The impact of corporate reputation on performance: Some Danish evidence. Eur. Manag. J. 2004, 22, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, G. How good corporate reputations create corporate value. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2006, 9, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thang, D.C.L.; Tan, B.B. Linking consumer perception to preference of retail stores: An empirical assessment of the multi-attributes of store image. J. Retail. Cons. Serv. 2003, 10, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C.J. Indices of corporate reputation: An analysis of media rankings and social monitors’ ratings. Corp. Reput. Rev. 1998, 1, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, N.J.; Cialdini, R.B.; Griskevicius, V. A room with a viewpoint: Using social norms to motivate environmental conservation in hotels. J. Cons. Res. 2008, 35, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroudi, P. Influence of brand signature, brand awareness, brand attitude, brand reputation on hotel industry’s brand performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.C.; Kastenholz, E. Corporate reputation, satisfaction, delight, and loyalty towards rural lodging units in Portugal. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Swanson, S.R.; Chinchanachokchai, S.; Hsu, M.K.; Chen, X. Reputation and intentions: The role of satisfaction, identification, and commitment. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3261–3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.-C. How reputation creates loyalty in the restaurant sector. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 25, 536–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.H.; Nguyen, B.; Lee, T.J. Consumer-based chain restaurant brand equity, brand reputation, and brand trust. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 50, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.H.C.; Oh, H.; Assaf, A.G. A customer-based brand equity model for upscale hotels. J. Trav. Res. 2012, 51, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H. Effect of brand popularity as an advertising cue on tourists’ shopping behavior. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 10, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, A.D.; Perkins, H.W. Problem drinking among college students: A review of recent research. J. Am. Coll. Health 1986, 35, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J. Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 2004, 55, 591–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnini, V.; Karande, K.; Singal, M.; Kim, D. The effect of brand popularity statements on consumers’ purchase intentions: The role of instrumental attributes toward the act. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Min, D.W. Consumers’ response to an advertisement using brand popularity in a foreign market. Jpn. Psychol. Res. 2016, 58, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chua, B.-L.; Lee, S.; Han, H. Consequences of cruise line involvement: A comparison of first-time and repeat passengers. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 1658–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Han, H. New or repeat customers: How does physical environment influence their restaurant experience? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The nature and determinants of customer expectations of service. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1993, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivela, J.; Inbakaran, R.; Reece, J. Consumer research in the restaurant environment. Part 3: Analysis, findings and conclusions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2000, 12, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, D.B.; Lin, C.H. Why do first-time and repeat visitors patronize a destination? J. Trav. Tour. Mark. 2010, 27, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beldona, S.; Moreo, A.P.; Mundhra, G.D. The role of involvement and variety-seeking in eating out behaviors. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 22, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlister, L.; Pessemier, E. Variety seeking behavior: An interdisciplinary review. J. Cons. Res. 1982, 9, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlyne, D.E. Conflict, Arousal, and Curiosity; Martino Publishing: Mansfield Centre, CT, USA, 2014; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Inman, J.J. The role of sensory-specific satiety in attribute-level variety seeking. J. Cons. Res. 2001, 28, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlister, L. A dynamic attribute satiation model of variety seeking behavior. J. Cons. Res. 1982, 9, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, J.E.M.; Baumgarter, N. The role of optimum stimulation level in exploratory consumer behavior. J. Cons. Res. 1992, 19, 434–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Chua, B.-L.; Han, H. Variety-seeking motivations and customer behaviors for new restaurants: An empirical comparison among full-service, quick-casual, and quick-service restaurants. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 43, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishen, A.S.; Bui, M.; Peter, P.C. Retail kiosks: How regret and variety influence consumption. Int. J. Retail Dist. Manag. 2010, 38, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Han, H. Influence of the quality of food, service, and physical environment on customer satisfaction and behavioral intention in quick-casual restaurants: Moderating role of perceived price. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2010, 34, 310–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okeiyi, E.C.; Finley, D.A. Consumers’ health consciousness: Impact on restaurant selection. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 1994, 5, 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-ends model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winer, R.S. A reference price model of brand choice for frequently purchased products. J. Cons. Res. 1986, 13, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalwani, M.U.; Yim, C.K.; Rinne, H.J.; Sugita, Y. A price expectations model of consumer brand choice. J. Mark. Res. 1990, 27, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwun, J.-W.; Oh, H. Effects of brand, price, and risk on customers’ value perceptions and behavioral intentions in the restaurant industry. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 2004, 11, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghubir, P.; Corfman, K.P. When do price promotions signal quality? The effect of dealing on perceived service quality. In NA—Advances in Consumer Research; Kardes, F.R., Sujan, M., Eds.; Association for Consumer Research: Provo, UT, USA, 1995; Volume 22, pp. 58–61. [Google Scholar]

- Raghubir, P.; Corfman, K.P. When do price promotions affect pretrial brand evaluations? J. Mark. Res. 1999, 36, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DelVecchio, D.; Henard, D.H.; Freling, T.H. The effect of sales promotion on post-promotion brand preference. J. Retail. 2006, 83, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandon, P.; Wansink, B.; Laurent, G. A benefit congruency framework of sales promotion effectiveness. J. Mark. 2000, 64, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A. Building Strong Brands: Building, Measuring, and Managing Brand Equity; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R.G. Sales response to promotions and advertising. J. Adv. Res. 1974, 14, 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.-C.; Chang, Y.-T.; Yeh, C.-Y.; Liao, C.-W. Promote the price promotion: The effects of price promotions on customer evaluations in coffee chain stores. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 26, 1065–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Landré, M.; Ryan, C. Restaurant location in Hamilton, New Zealand: Clustering patterns from 1996 to 2008. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 24, 430–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.L.J. Restaurants and dining out: Geography of a tourism business. Ann. Tour. Res. 1983, 10, 515–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-F.; Tsai, C.-T. Data mining framework based on rough set theory to improve location selection decisions: A case study of a restaurant chain. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillsbury, R. From Hamburger Alley To Hedgerose Heights: Toward a model of restaurant location dynamics. Prof. Geog. 1987, 39, 326–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camillo, A.A.; Connolly, D.J.; Kim, W.G. Success and failure in Northern California: Critical success factors for independent restaurants. Cornell Hosp. Quart. 2008, 49, 364–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Roehl, W.S.; Huang, J.-H. Understanding and projecting the restaurantscape: The influence of neighborhood sociodemographic characteristics on restaurant location. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 67, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivela, J.J. Restaurant marketing: Selection and segmentation in Hong Kong. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 1997, 9, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, D.R. Customers’ expectations factors in restaurants: The situation in Spain. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2002, 19, 1055–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canziani, B.F.; Almanza, B.; Frash, R.E., Jr.; McKeig, M.J.; Sullivan-Reid, C. Classifying restaurants to improve usability of restaurant research. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 1467–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutson, B.J. College students and fast food: How students perceive restaurant brands. Cornell Hotel Rest. Admin. Quart. 2000, 41, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.S. Benefit dimensions of midscale restaurant chains. Cornell Hotel Rest. Admin. Quart. 1993, 34, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- June, L.P.; Smith, S.L.J. Service attributes and situational effects on customer preferences for restaurant dining. J. Trav. Res. 1987, 26, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namin, A. Revisiting customers’ perception of service quality in fast food restaurants. J. Retail Cons. Serv. 2017, 34, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaysia Tourism. Tourism Malaysia Launches Miss SHOPhia Shopping Hunt 2.0 Campaign. Available online: https://www.tourism.gov.my/media/view/tourism-malaysia-launches-miss-shophia-shopping-hunt-2-0-campaign (accessed on 25 November 2017).

- Raju, P.S. Optimum stimulation level: Its relationship to personality, demographics, and exploratory behavior. J. Cons. Res. 1980, 7, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GlobalData. Malaysia—The Future of Foodservice to 2021. Available online: https://store.globaldata.com/report/cs0030fs--malaysia-the-future-of-foodservice-to-2021/ (accessed on 1 July 2017).

- Wahab, A.G. Report of the Malaysia Food Service. Available online: https://gain.fas.usda.gov/Recent%20GAIN%20Publications/Food%20Service%20-%20Hotel%20Restaurant%20Institutional_Kuala%20Lumpur_Malaysia_11-16-2017.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2017).

- Han, H.; Ryu, K. The roles of the physical environment, price perception, and customer satisfaction in determining customer loyalty in the restaurant industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2009, 33, 487–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varki, S.; Colgate, M. The role of price perceptions in an integrated model of behavioral intentions. J. Serv. Res. 2001, 3, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R.C. Advertising your hotel’s position. Cornell Hotel Rest. Admin. Quart. 1990, 31, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longart, P. What drives word-of-mouth in restaurants? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 22, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Lee, H.-R.; Kim, W.G. The influence of the quality of the physical environment, food, and service on restaurant image, customer perceived value, customer satisfaction, and behavioral intentions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 24, 200–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rank | Restaurant Choice Factors | Mean ± Std. Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Price | 3.798 ± 2.558 | 0.588 | −0.887 |

| 2 | Word-of-mouth | 4.588 ± 2.692 | 0.168 | −1.327 |

| 3 | Personal/past experience | 4.757 ± 2.551 | 0.040 | −1.173 |

| 4 | Variety of menu items | 4.811 ± 2.442 | 0.172 | −1.082 |

| 5 | Popularity | 4.811 ± 2.363 | 0.076 | −1.041 |

| 6 | Reputation | 4.839 ± 2.402 | 0.018 | −1.137 |

| 7 | Location | 5.182 ± 2.604 | −0.053 | −1.283 |

| 8 | Sales promotion | 6.095 ± 2.367 | −0.497 | −0.910 |

| 9 | Online review from customers | 6.115 ± 2.426 | −0.419 | −0.942 |

| Restaurant Choice Factors | Mean ± Std. Deviation | t-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Price | 3.798 ± 2.558 | −4.207 *** | 0.000 |

| Word-of-mouth | 4.588 ± 2.692 | ||

| Word-of-mouth | 4.588 ± 2.692 | −0.962 | 0.336 |

| Personal/past experience | 4.757 ± 2.551 | ||

| Personal/past experience | 4.757 ± 2.551 | −0.349 | 0.727 |

| Variety of menu items | 4.811 ± 2.442 | ||

| Variety of menu items | 4.811 ± 2.442 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Popularity | 4.811 ± 2.363 | ||

| Popularity | 4.811 ± 2.363 | −0.224 | 0.823 |

| Reputation | 4.839 ± 2.402 | ||

| Reputation | 4.839 ± 2.402 | −1.934 | 0.054 |

| Location | 5.182 ± 2.604 | ||

| Location | 5.182 ± 2.604 | −6.706 *** | 0.000 |

| Sales promotion | 6.095 ± 2.367 | ||

| Sales promotion | 6.095 ± 2.367 | −0.125 | 0.901 |

| Online review from customers | 6.115 ± 2.426 |

| Restaurant Choice Factors | Occasions | Mean ± Std. Deviation | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Word-of-mouth | Quick meal | 4.925 ± 2.739 | 3.623 * | 0.013 |

| Social occasion | 4.543 ± 2.659 | |||

| Business necessity | 4.103 ± 2.440 | |||

| Celebration | 3.927 ± 2.580 | |||

| Online review from customers | Quick meal | 6.504 ± 2.311 | 4.944 ** | 0.002 |

| Social occasion | 5.963 ± 2.566 | |||

| Business necessity | 5.414 ± 2.147 | |||

| Celebration | 5.563 ± 2.410 | |||

| Reputation | Quick meal | 5.131 ± 2.350 | 5.073 ** | 0.002 |

| Social occasion | 4.827 ± 2.471 | |||

| Business necessity | 3.483 ± 2.064 | |||

| Celebration | 4.500 ± 2.362 | |||

| Popularity | Quick meal | 5.012 ± 2.275 | 3.692 * | 0.012 |

| Social occasion | 4.506 ± 2.420 | |||

| Business necessity | 3.828 ± 2.019 | |||

| Celebration | 5.094 ± 2.488 | |||

| Personal/past experience | Quick meal | 4.571 ± 2.610 | 3.012 * | 0.030 |

| Social occasion | 4.654 ± 2.370 | |||

| Business necessity | 4.621 ± 2.871 | |||

| Celebration | 5.458 ± 2.509 | |||

| Variety of menu items | Quick meal | 4.631 ± 2.427 | 1.832 | 0.140 |

| Social occasion | 4.852 ± 2.268 | |||

| Business necessity | 5.690 ± 2.647 | |||

| Celebration | 4.948 ± 2.661 | |||

| Price | Quick meal | 3.508 ± 2.476 | 3.999 ** | 0.008 |

| Social occasion | 3.784 ± 2.531 | |||

| Business necessity | 4.931 ± 2.815 | |||

| Celebration | 4.240 ± 2.615 | |||

| Sales promotion | Quick meal | 6.024 ± 2.336 | 2.693 * | 0.045 |

| Social occasion | 6.259 ± 2.397 | |||

| Business necessity | 7.035 ± 1.426 | |||

| Celebration | 5.719 ± 2.549 | |||

| Location | Quick meal | 4.706 ± 2.547 | 5.552 ** | 0.001 |

| Social occasion | 5.593 ± 2.594 | |||

| Business necessity | 5.897 ± 2.730 | |||

| Celebration | 5.521 ± 2.550 |

| Restaurant Choice Factors | Restaurant Types | Mean ± Std. Deviation | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Word-of-mouth | Full-service | 4.496 ± 2.632 | 1.153 | 0.316 |

| Quick-casual | 4.886 ± 2.754 | |||

| Quick-service | 4.440 ± 2.775 | |||

| Online review from customers | Full-service | 6.022 ± 2.401 | 0.395 | 0.674 |

| Quick-casual | 6.242 ± 2.542 | |||

| Quick-service | 6.152 ± 2.393 | |||

| Reputation | Full-service | 4.891 ± 2.384 | 0.095 | 0.909 |

| Quick-casual | 4.780 ± 2.590 | |||

| Quick-service | 4.848 ± 2.279 | |||

| Popularity | Full-service | 4.775 ± 2.415 | 0.045 | 0.956 |

| Quick-casual | 4.833 ± 2.282 | |||

| Quick-service | 4.840 ± 2.329 | |||

| Personal/past experience | Full-service | 4.594 ± 2.654 | 4.561 * | 0.011 |

| Quick-casual | 4.530 ± 2.260 | |||

| Quick-service | 5.352 ± 2.515 | |||

| Variety of menu items | Full-service | 4.612 ± 2.415 | 3.092 * | 0.046 |

| Quick-casual | 4.796 ± 2.291 | |||

| Quick-service | 5.264 ± 2.609 | |||

| Price | Full-service | 3.866 ± 2.436 | 0.645 | 0.525 |

| Quick-casual | 3.886 ± 2.811 | |||

| Quick-service | 3.576 ± 2.547 | |||

| Sales promotion | Full-service | 6.467 ± 2.325 | 9.493 *** | 0.000 |

| Quick-casual | 5.977 ± 2.352 | |||

| Quick-service | 5.384 ± 2.327 | |||

| Location | Full-service | 5.232 ± 2.576 | 0.131 | 0.877 |

| Quick-casual | 5.091 ± 2.593 | |||

| Quick-service | ± 2.678 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chua, B.-L.; Karim, S.; Lee, S.; Han, H. Customer Restaurant Choice: An Empirical Analysis of Restaurant Types and Eating-Out Occasions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6276. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176276

Chua B-L, Karim S, Lee S, Han H. Customer Restaurant Choice: An Empirical Analysis of Restaurant Types and Eating-Out Occasions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(17):6276. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176276

Chicago/Turabian StyleChua, Bee-Lia, Shahrim Karim, Sanghyeop Lee, and Heesup Han. 2020. "Customer Restaurant Choice: An Empirical Analysis of Restaurant Types and Eating-Out Occasions" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 17: 6276. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176276

APA StyleChua, B.-L., Karim, S., Lee, S., & Han, H. (2020). Customer Restaurant Choice: An Empirical Analysis of Restaurant Types and Eating-Out Occasions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(17), 6276. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176276