Implementation Models of Compassionate Communities and Compassionate Cities at the End of Life: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Models from the health services to the community (top-down approach).

- Models from community participation through the development of actions and events that involve communities in the promotion of their health (bottom-up approach).

- Models from organizations and community participation that ensure that population needs and desires are covered by the community’s impulse and offer tools and techniques to assess these needs and propose solutions.

- Has local health policies that recognize compassion as an ethical imperative.

- Meets the special needs of elders, those living with life-threatening illnesses, and those living with loss.

- Has a strong commitment to social and cultural differences.

- Involves grief and palliative care services in local government policy and planning.

- Offers its inhabitants access to a wider variety of supportive experiences, interactions and communication.

- Promotes and celebrates reconciliation with indigenous peoples and memory of other important community losses.

- Provides easy access to grief and palliative care services.

- Death, dying and bereavement would cease to be taboo subjects and would become more normalized within society.

- People’s expectations of death and dying will change, as well as how death will be managed.

- Palliative care will be re-oriented, supporting health and social care staff to work with the community in providing care to those at the end of life and their loved ones.

- How many end of life Compassionate Communities and Cities development models exist?

- What are their methods, processes and measures to allow the intervention assessment?

- Could we compare different degrees of development of Compassionate Communities and Cities in different countries and organizations?

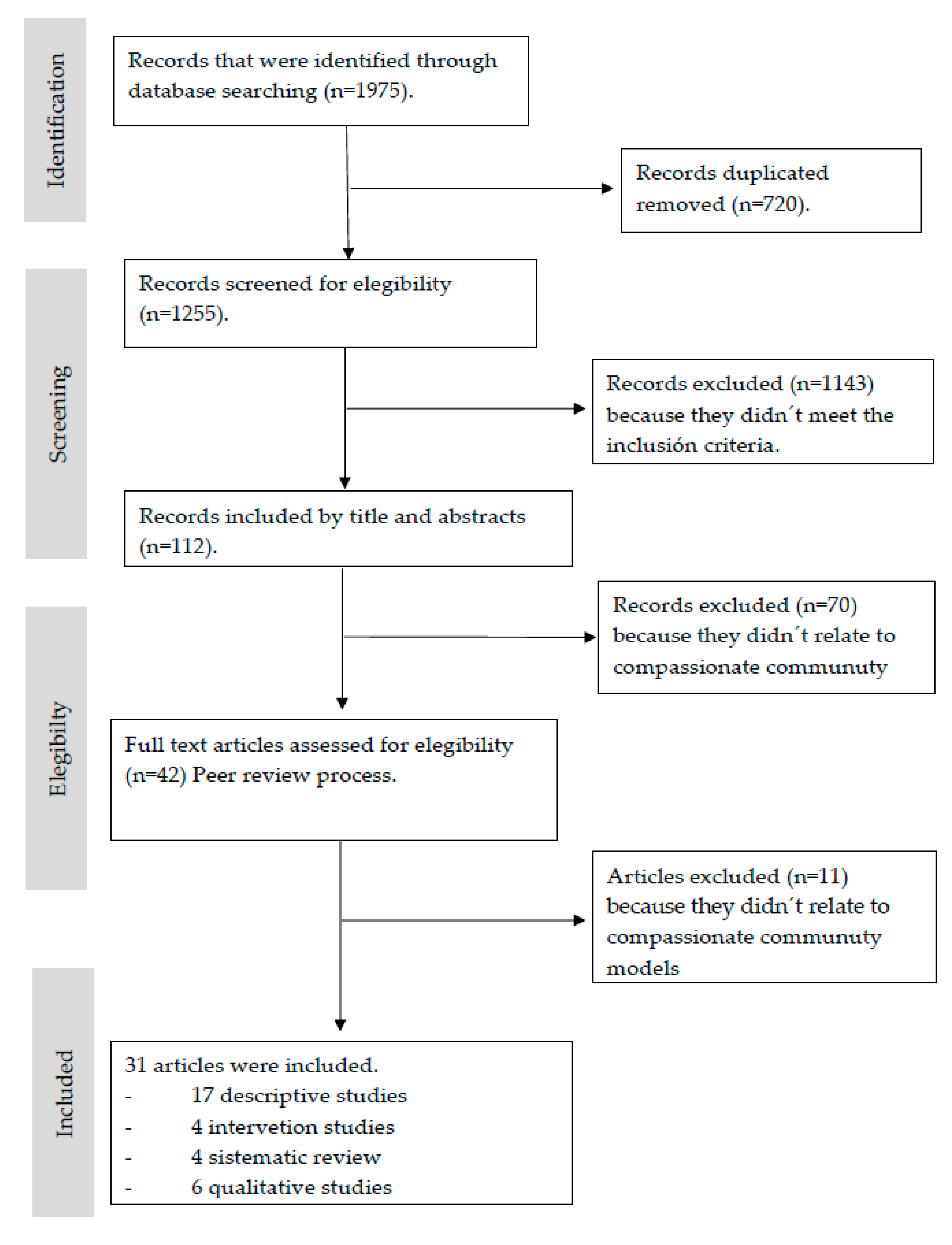

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Study Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Type of Studies

2.5. Quality Assessment

2.6. Screening and Data Extraction

- Does the article discuss Compassionate Communities and Cities at the end of life?

- Do they regard the development model of Compassionate Communities and Cities?

- Do they show the phases of development or standards?

- Are the development experiences and results of Compassionate Communities and Cities discussed?

- Is it a pilot study?

- Is the development method described?

- Do they describe tools and resources used to develop Compassionate Communities and Cities?

- Was it developed from public policies in palliative care?

2.7. Data Analysis

- Objectives: What do they want to achieve at city, organization, country level?

- Scope: What is the scope or coverage?

- Development models How do they do it?

- Degree of development: pilot, initial or consolidated

- Standards: Are there goals to be achieved? What are the standards to achieve them?

- Tools, resources, evaluation models and analysis of results.

3. Results

3.1. Compassionate Community or Cities at the End of Life Development Models (Theme 1)

3.2. Evaluation Models of Compassionate Communities and Cities: Indicators, Standards or Data That Allow Evaluating the Organizations and Resources (Theme 2)

- Compassionate Communities and Cities evaluation models/ systems.

- Evaluation of specific Compassionate Communities and Cities programs.

- Evaluation of compassion practice.

3.2.1. Compassionate Communities and Cities Evaluation Models/Systems

- Overarching Structures: Patient and Family-Centered Care,

- Overarching Values: Empathy, Sharing, Respect, Partnership.

- Process indicators: Communication, Shared decision-making, Goal setting;

- Results indicators: organizational development and satisfaction.

3.2.2. Compassionate Communities and Cities Evaluation Models/ Systems

- Providers underwent semi-structured telephone interviews on aspects related to Compassionate Care Benefit usefulness, its access facilitators and barriers; experiences related to recommending the Compassionate Care Benefit to potential applicants and suggestions for program improvement [31].

- The visibility of the program: web, marketing materials, brochures, awareness campaigns, etc.

- Citizen participation: community groups, volunteering, conversation groups, workshops, etc.

- The social care model: Community mentors, community partners, voluntary community mentors recruited and trained, community mentors advertised in the designated areas and with all appropriate service providers.

3.2.3. Compassionate Communities and Cities Evaluation Models/Systems

3.3. Compassionate Communities and Cities: Tools, Protocols or Information Systems (Theme 3)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion; World Health Organization: Chicago, IL, USA, 1986; Available online: https://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en/ (accessed on 10 July 2019).

- Abel, J.; Kellehear, A.; Karapliagou, A. Palliative care-the new essentials. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2018, 7 (Suppl. 2), S3–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kellehear, A. Compassionate Cities: Public Health and End-of-Life Care; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, S.; Sallnow, L. Public health approaches to end-of-life care in the UK: An online survey of palliative care services. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2013, 3, 196–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazelwood, M.; Patterson, R. Scotland’s public health palliative care alliance. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2018, 7 (Suppl. 2), S109–S117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLoughlin, K.; Rhatigan, J.; McGilloway, S.; Kellehear, A.; Lucey, M.; Twomey, F.; Conroy, M.; Herrera-Molina, E.; Kumar, S.; Furlong, M.; et al. INSPIRE (INvestigating Social and Practical supports at the End of life): Pilot randomized trial of a community social and practical support intervention for adults with life-limiting illness. BMC Palliat. Care 2015, 14, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wegleitner, K.; Schuchter, P. Caring communities as collective learning process: Findings and lessons learned from a participatory research project in Austria. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2018, 7 (Suppl. 2), S84–S98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S. Kerala, India: A Regional Community-Based Palliative Care Model. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2007, 33, 623–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pesut, B.; Duggleby, W.; Warner, G.; Fassbender, K.; Antifeau, E.; Hooper, B.; Greig, M.; Sullivan, K. Volunteer navigation partnerships: Piloting a compassionate community approach to early palliative care. BMC Palliat. Care 2017, 17, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, J.P.; Horsfall, D.; Leonard, R.; Noonan, K. Informal caring networks for people at end of life: Building social capital in Australian communities. Health Sociol. Rev. 2015, 24, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, E.; Librada, S.; Samudio, M.L.; Ronderos, C.; Krikorian, A.; Vélez, M.C. Colombia is with You, Compassionate Cities. In Proceedings of the 5th International Public Health and Palliative Care Conference, Ottawa, MI, Canada, 17–20 September 2017; Available online: http://phpci.info/phpc17 (accessed on 20 September 2017).

- Librada, S.; Herrera, E.; Boceta, J.; Mota, R.; Nabal, M. All with you: A new method for developing compassionate communities-experiences in Spain and Latin-America. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2018, 7 (Suppl. 2), S15–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Batiste, X.; Mateu, S.; Serra-Jofre, S.; Molas, M.; Mir-Roca, S.; Amblàs, J.; Costa, X.; Lasmarías, C.; Serrarols, M.; Solá-Serrabou, A.; et al. Compassionate communities: Design and preliminary results of the experience of Vic (Barcelona, Spain) caring city. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2018, 7 (Suppl. 2), S32–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brito, G.; Librada, S. Compassion in palliative care: A review. Curr. Opin. Support Palliat. Care 2018, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Molina, E.; Jadad-García, T.; Librada, S.; Álvarez, A.; Rodríguez, Z.; Lucas, M.A.; Jadad, A.R. Beginning from the End: The Power of Health and Social Services and the Community during the Last Stages of Life. New Health Foundation. 2017. Available online: http://www.newhealthfoundation.org/informes-y-publicaciones/ (accessed on 10 July 2017).

- Lown, B. Seven guiding commitments: Making the U.S. healthcare system more compassionate. J. Patient. Exp. 2014, 1, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abel, J.; Bowra, J.; Howarth, G. Compassionate community networks: Supporting home dying. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2011, 1, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Zulueta, P. Developing compassionate leadership in health care: An integrative review. J. Health Leadersh. 2016, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chou, W.Y.; Stokes, S.; Citko, J.; Davies, B. Improving end-of-life care through community-based grassroots collaboration: Development of the Chinese-American Coalition for Compassionate Care. J. Palliat. Care 2008, 24, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallnow, L.; Kumar, S.; Numpeli, M. Home-based palliative care in Kerala, India: The Neighbourhood Network in Palliative Care. Prog. Palliat. Care 2010, 18, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinderman, C. Palliative care, public health and justice: Setting priorities in resource poor countries. Dev. World Bioeth. 2009, 9, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayser, J.; Chan, J.; Kris, A. A model long term care hospice unit: Care, Community and Compassion. Geriatr. Nurs. 2005, 26, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, J.; Walter, T.; Carey, L.; Rosenberg, J.; Noonan, K.; Horsfall, D.; Leonard, R.; Rumbolod, B.; Morris, D. Circles of care: Should community development redefine the practice of palliative care? BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2013, 3, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flager, J.; Dong, W. The uncompassionate elements of the Compassionate Care Benefits Program: A critical analysis. Glob. Health Promot. 2010, 17, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellehear, A. Compassionate communities: End-of-life care as everyone’s responsibility. QJM Int. J. Med. 2013, 106, 1071–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sallnow, L.; Richardson, H.; Murray, S.; Kellehear, A. The impact of a new public health approach to end-of-life care: A systematic review. Palliat. Med. 2016, 30, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfaff, K.; Markaki, A. Compassionate collaborative care: An integrative review of quality indicators in end-of-life care. BMC Palliat. Care 2017, 16, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luzinski, C.; Stockbridge, E.; Craighead, J.; Bayliss, D.; Schmidt, M.; Seideman, J. The Community Case Management Program: For 12 Years, Caring at Its Best. Geriatr. Nurs. 2008, 29, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooks, V.A.; Williams, A.; Stajduhar, K.I.; Cohen, S.R.; Allan, D.; Brazil, K. Family caregivers’ ideal expectations of Canada’s Compassionate Care Benefit. Health Soc. Care Commun. 2012, 20, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.M.; Eby, J.A.; Crooks, V.A.; Stajduhar, K.; Giesbrecht, M.; Vukan, M.; Cohen, S.R.; Brazil, K.; Allan, D. Canada’s Compassionate Care Benefit: Is it an adequate public health response to addresing the issue of caregiver burden in end of life care? BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.M. Evaluating Canada’s Compassionate Care Benefit using a utilization-focused evaluation framework: Successful strategies and prerequisite conditions. Eval. Progr. Plann. 2010, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giesbrecht, M.; Crooks, V.A.; Williams, A.; Hankivsky, O. Critically examining diversity in end-of-life family caregiving: Implications for equitable caregiver support and Canada’s Compassionate Care Benefit. Int. J. Equity Health 2012, 11, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Giesbrecht, M.; Crooks, V.A.; Williams, A. Perspectives from the frontlines: Palliative care provider´s expectations of Canada’s compassionate care benefit programme. Health Soc. Care Commun. 2010, 18, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLoughlin, K. Compassionate Communities Project Evaluation Report. 2013. Available online: https://www.lenus.ie/handle/10147/621066 (accessed on 10 September 2019).

- Crowther, J.; Wilson, K.C.M.; Horton, S.; Lloyd-Willians, M. Compassion in healthcare-lessons from a qualitative study of the end of life care of people with dementia. J. R. Soc. Med. 2013, 106, 492–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martins, D.; Nicholas, N.A.; Shaheen, M.; Jones, L.; Norris, K. The development and evaluation of a Compassion Scale. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2013, 24, 1235–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinclair, S.; Norris, J.M.; McConnell, S.J.; Chochinov, H.M.; Hack, T.F.; Hagen, N.A.; McClement, S.; Raffin, S. Compassion: A scoping review of the healthcare literature. BMC Palliat. Care 2016, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sinclair, S.; McClement, S.; Raffin-Bouchal, S.; Hack, T.F.; Hagen, N.A.; McConnell, S.; Chochinov, H.M. Compassion in health care: An empirical model. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2016, 51, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shih, C.-Y.; Hu, W.-Y.; Lee, L.-T.; Yao, C.A.; Chen, C.-Y.; Chiu, T.-Y. Effect of a Compassion-Focused Training Program in Palliative Care Education for Medical Students. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2012, 30, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewar, B.; Cook, F. Developing compassion through a relationship centred appreciative leadership programme. Nurse Educ. Today 2014, 34, 1258–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, K.J.; Candy, B.; Davis, S.; Gola, A.; Harrington, J.; Kupeli, N.; Vickerstaff, V.; King, M.; Leavy, G.; Nazareth, I.; et al. Implementing the compassion intervention, a model for integrated care for people with advanced dementia towards the end of life in nursing homes: A naturalistic feasibility study. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e015515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, M.; Harrington, J.; Moore, K.; Davis, S.; Kupeli, N.; Vickerstaff, V.; Gola, A.; Candy, B.; Sampsom, E.L.; Jones, L. A protocol for an exploratory phase I mixed-methods study of enhanced integrated care for care home residents with advanced dementia: The compassion intervention. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e005661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walshe, C.; Pérez, G.; Dodd, S.; Hill, M.; Ockenden, N.; Payne, S.; Preston, N. Protocol for the End-of-Life Social Action Study (ELSA): A randomised wait-list controlled trial and embedded qualitative case study evaluation assessing the causal impact of social action befriending services on end of life experience. BMC Palliat. Care 2016, 15, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijay, D.; Monin, P. Poisedness for social innovation: The genesis and propagation of community-based palliative care in Kerala (India). Management 2018, 21, 1329–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Case Study: The Frome Model of Enhanced Primary Care. Available online: https://shiftdesign.org/case-study-compassionate-frome/ (accessed on 10 July 2019).

- Librada, S.; Herrera, E.; Díaz, F.; Redondo, M.J.; Castillo, C.; McLoughlin, K.; Abel, J.; Jadad, T.; Lucas, M.A.; Trabado, I.; et al. Development and management of networks of care at the end of life (the REDCUIDA Intervention): Protocol for a Nonrandomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2018, 12, e10515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Search Strategy |

|---|

| (Terminal Care OR Palliative Care OR Hospice Care OR Hospices) AND |

| (Community networks OR Community health planning OR Community participation OR Social supports OR Volunteers OR Social network) AND |

| (Governments OR policymaker OR health and social policy OR public policy) AND |

| (Empathy OR Compassion) AND |

| (Model OR Organizational OR Program development OR Standards OR Impact OR Evaluation OR measure OR outcome) AND |

| (Efficiency OR effectiveness OR efficacy OR impact OR excellence OR referral) |

| Type of Documents |

|

| Information Contained in these Types of Documents |

|

| Technical Criteria for the Search |

|

| Types of Studies |

|

| Number: |

|---|

| Title: |

| First Author Year: |

| Reference: |

| Document (select X) |

| National strategies, Framework Programs, Strategic Plans and Reports, |

| Consensus documents of associations, institutions, groups of professionals, scientific societies, expert panels, etc. related to the theme. |

| Reports and studies evaluating the results of the development of Compassionate Communities and Compassionate Cities. |

| Resolutions and political reports, |

| Books, White papers, |

| Tools and guides for program evaluation and measurement of indicators, |

| Scientific articles, |

| Grey literature: theses, books, book chapters. |

| Type of Study (select X) |

| Descriptive, retrospective and / or prospective studies |

| Comparative Studies |

| Evaluation studies |

| Intervention studies |

| Systematic reviews |

| Meta-analysis |

| Case study, ethnographic study, grounded theory study. |

| Risk of Bias Assessment (Select X) |

| Discuss articles about compassionate communities at the end of life? |

| Do they express Compassionate Communities and cities development models? |

| Do they expose development phases or standards? |

| Are development experiences and results discussed? |

| Are these pilot studies? |

| Is the development method described? |

| Do they describe tools and resources to develop Compassionate Communities and cities? |

| Is it development from public policies in palliative care? |

| Accepted (Select X) |

| Articles or other types of documents incomplete or in the process of being drawn up, |

| Documents that do not include information related to the object of the search, |

| Documents in other languages than English and Spanish. |

| Information Contained (Select X) |

| Models of community development and compassionate cities at the end of life. |

| Evaluation models of Compassionate Communities and Compassionate Cities. |

| Indicators, standards, or data that allow evaluating the organizations and resources. |

| Tools and information systems that allow the evaluation of Compassionate Communities and Compassionate Cities. |

| National regulations and public health models that establish the strategic lines for the development of communities and compassionate cities. |

| Primary Results |

| Dimension (What is the scope? coverage?) |

| Objective (What do you want to achieve at city, organization, country level?) |

| Development model (How do they do it?) |

| Degree of development (what stage are they in?) |

| Standards (Are there goals to be achieved? What are the standards for achieving this?) |

| Tools and resources. |

| Models of evaluation, reporting and analysis of results. |

| Narrative Summary of the Main Results |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Librada-Flores, S.; Nabal-Vicuña, M.; Forero-Vega, D.; Muñoz-Mayorga, I.; Guerra-Martín, M.D. Implementation Models of Compassionate Communities and Compassionate Cities at the End of Life: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6271. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176271

Librada-Flores S, Nabal-Vicuña M, Forero-Vega D, Muñoz-Mayorga I, Guerra-Martín MD. Implementation Models of Compassionate Communities and Compassionate Cities at the End of Life: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(17):6271. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176271

Chicago/Turabian StyleLibrada-Flores, Silvia, María Nabal-Vicuña, Diana Forero-Vega, Ingrid Muñoz-Mayorga, and María Dolores Guerra-Martín. 2020. "Implementation Models of Compassionate Communities and Compassionate Cities at the End of Life: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 17: 6271. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176271

APA StyleLibrada-Flores, S., Nabal-Vicuña, M., Forero-Vega, D., Muñoz-Mayorga, I., & Guerra-Martín, M. D. (2020). Implementation Models of Compassionate Communities and Compassionate Cities at the End of Life: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(17), 6271. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176271