Practical Recommendations for Maintaining Active Lifestyle during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The survey branch addresses the behavioral and lifestyle consequences of COVID-19 restrictions of the population during different pandemic stages [13,14,15].The main findings from Europe, Western Asia, North-Africa, and America showed that the COVID-19 home confinement had a negative effect on social activity [15] and all PA intensity levels [13,14], with the number of days per week of PA lowered by 22.7%, 24%, 35%, respectively, for vigorous intensity, moderate intensity, and walking. Additionally, the total weekly PA (MET-min·week-1) was 38% lower during home confinement, while daily sitting time increased from 5 to 8 h per day [13,14] Subgroup analyses addressing different target groups and confinement levels will follow.

- The review branch started with an early review on the effects of quarantine and social distancing on well-being and other psychological aspects, which summarized possible recommendations for staying physically active as a mitigation of these effects and risks [16]. The present systematic review aims to identify, evaluate, and summarize existent practical recommendations to promote PA during the actual pandemic or any other isolation period.

- The intervention branch will build on the published results of the other branches and will in return contribute to them. It is in the grant application phase and will be reported elsewhere.

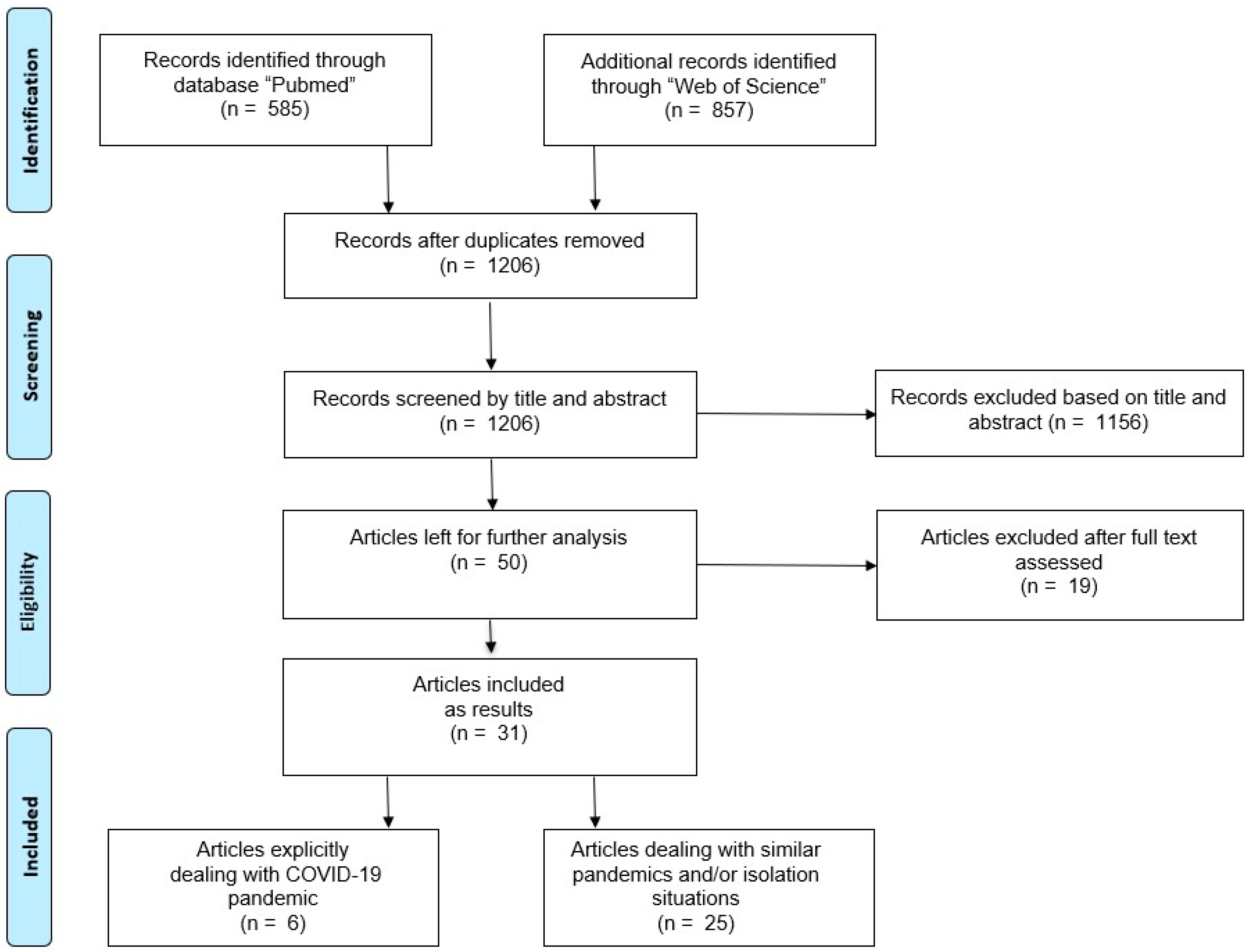

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Maintaining or Improving the Physical Activity Levels during the COVID-19 Pandemic

- (i)

- (ii)

- modulate the severity of the infection by supporting the immune system and improving metabolic health [27];

- (iii)

3.2. Useful Results for an Active Lifestyle during Pandemics

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Recommendations

- “10 min of stretching is like walking the length of a football field”;

- “2.5 h of walking every week for a year is like walking across the state of Wyoming”;

- “30 min of singles tennis is like walking a 5K”;

- “1 h of dancing every week for a year is like walking from Chicago to Indianapolis”;

- “20 min of vacuuming is like walking one mile”;

- “30 min of grocery shopping every other week for a year is like walking a marathon” [74].

4.2. Methodological Quality

4.3. Strengths and Weaknesses

4.4. Further Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 28 June 2020).

- WHO. Announces COVID-19 Outbreak a Pandemic. Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/news/news/2020/3/who-announces-covid-19-outbreak-a-pandemic (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- Jiang, X.; Niu, Y.; Li, X.; Li, L.; Cai, W.; Chen, Y.; Liao, B.; Wang, E. Is a 14-day quarantine period optimal for effectively controlling coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID19)? Medrxiv Prepr. 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarımkaya, E.; Esentürk, O.K. Promoting physical activity for children with autism spectrum disorders during Coronavirus outbreak: Benefits, strategies, and examples. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 2020, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, B.; Kobel, S.; Wartha, O.; Kettner, S.; Dreyhaupt, J.; Steinacker, J.M. High sedentary time in children is not only due to screen media use: A cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatrics 2019, 19, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roschel, H.; Artioli, G.G.; Gualano, B. Risk of increased physical inactivity during COVID-19 outbreak in older people: A call for actions. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 1126–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Impact of Coronavirus on Global Activity. Available online: https://blog.fitbit.com/covid-19-global-activity/ (accessed on 25 March 2020).

- Hallal, P.C.; Andersen, L.B.; Bull, F.C.; Guthold, R.; Haskell, W.; Ekelund, U. Global physical activity levels: Surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet 2012, 380, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohrn, I.M.; Kwak, L.; Oja, P.; Sjöström, M.; Hagströmer, M. Replacing sedentary time with physical activity: A 15-year follow-up of mortality in a national cohort. Clin. Epidemiol. 2018, 10, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Physical Activity. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity (accessed on 6 July 2020).

- Grande, A.J.; Keogh, J.; Silva, V.; Scott, A.M. Exercise versus no exercise for the occurrence, severity, and duration of acute respiratory infections. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 4, 1–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modeling Study Suggests 18 Months of COVID-19 Social Distancing, Much Disruption. Available online: https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/news-perspective/2020/03/modeling-study-suggests-18-months-covid-19-social-distancing-much (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- Ammar, A.; Brach, M.; Trabelsi, K.; Chtourou, H.; Boukhris, O.; Masmoudi, L.; Bouaziz, B.; Bentlage, E.; How, D.; Ahmed, M.; et al. On Behalf of the ECLB-COVID19 Consortium. Effects of COVID-19 home confinement on eating behaviour and physical activity: Results of the ECLB-COVID19 international online survey. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, A.; Trabelsi, K.; Brach, M.; Chtourou, H.; Boukhris, O.; Masmoudi, L.; Bouatit, B.; Bentlage, E.; How, D.; Ahmed, M.; et al. On Behalf of the ECLB-COVID19 Consortium. Effects of home confinement on mental health and lifestyle behaviours during the COVID-19 outbreak: Insight from the ECLB-COVID19 multicenter study. Biol. Sport 2020, 38, 2021, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, A.; Chtourou, H.; Boukhris, O.; Trabelsi, K.; Masmoudi, L.; Brach, M.; Bouaziz, B.; Bentlage, E.; How, D.; Ahmed, M.; et al. COVID-19 Home Confinement Negatively Impacts Social Participation and Life Satisfaction: A Worldwide Multicenter Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chtourou, H.; Trabelsi, K.; H´mida, C.; Boukhris, O.; Brach, M.; Bentlage, E.; Ammar, A.; Glenn, J.M.; Bott, N.; Shephard, E.J.; et al. Staying physically active during the quarantine and self-isolation period for controlling and mitigating the COVID-19 pandemics: A systematic overview of the literature. Front. Psycho 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitsch, J.R. Motivation reconsidered—An action-logical approach. In New Approaches to Sport and Exercise Psychology; Stelter, R., Roessler, K.K., Eds.; Meyer & Meyer Sport: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 55–82. ISBN 1-84126-149-1. [Google Scholar]

- Brach, M.; Bremer, A.; Kretschmer, A.; Laurila-Dürsch, J.; Naumann, S.; Reiß, C. Standardisation for mobility-related assisted living solutions: From problem analysis to a generic mobility model. In Ambient Assisted Living; Wichert, R., Mand, B., Eds.; Springer: Cham/Frankfurt, Germany, 2017; pp. 197–213. ISBN 978-3-319-52322-4. [Google Scholar]

- MeSH Medical Subject Headings. Available online: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/meshhome.html#:~:text=The%20Medical%20Subject%20Headings%20%28MeSH%29%20thesaurus%20is%20a,cataloging%2C%20and%20searching%20of%20biomedical%20and%20health-related%20information (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- Hinrichs, T.; Brach, M. The general practitioner’s role in promoting physical activity to older adults: A review based on program theory. Curr. Aging Sci. 2012, 5, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rütten, A.; Abu-Omar, K.; Burlacu, I.; Gediga, G.; Messing, S.; Pfeifer, K.; Ungerer-Röhrich, U. Recommendations for physical activity promotion. In National Recommendations for Physical Activity and Physical Activity Promotion; Rütten, A., Pfeifer, K., Eds.; Fau University Press: Erlangen, Germany, 2016; pp. 69–86. ISBN 978-3-944057-97-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ackley, B.J.; Swan, B.A.; Ladwig, G.; Tucker, S. Evidence-Based Nursing Care Guidelines: Medical-Surgical Interventions; Mosby Elsevier: St. Louis, MI, USA, 2008; p. 7. ISBN 9780323046244. [Google Scholar]

- Altena, E.; Baglioni, C.; Espie, C.A.; Ellis, J.; Gavriloff, D.; Holzinger, B.; Schlarb, A.; Frase, L.; Jernelöv, S.; Riemann, D. Dealing with sleep problems during home confinement due to the COVID-19 outbreak: Practical recommendations from a task force of the European CBT-I Academy. J. Sleep Res. 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chevance, A.; Gourion, D.; Hoertel, N.; Llorca, P.M.; Thomas, P.; Bocher, R.; Moro, M.R.; Laprévote, V.; Benyamina, A.; Fossati, P.; et al. Ensuring mental health care during the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in France: A narrative review. L’Encephale 2020, 46, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luzi, L.; Radaelli, M.G. Influenza and obesity: Its odd relationship and the lessons for COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Diabetol. 2020, 57, 759–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narici, M.; de Vito, G.; Franchi, M.; Paoli, A.; Moro, T.; Marcolin, G.; Grassi, B.; Baldassarre, G.; Zuccarelli, L.; Biolo, G.; et al. Impact of sedentarism due to the COVID-19 home confinement on neuromuscular, cardiovascular and metabolic health: Physiological and pathophysiological implications and recommendations for physical and nutritional countermeasures. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2020, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peçanha, T.; Goessler, K.F.; Roschel, H.; Gualano, B. Social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic can increase physical inactivity and the global burden of cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2020, 318, 1441–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrobelli, A.; Pecoraro, L.; Ferruzzi, A.; Heo, M.; Faith, M.; Zoller, T.; Antoniazzi, F.; Piacentini, G.; Fearnbach, S.N.; Heymsfield, S.B. Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on lifestyle behaviors in children with obesity living in Verona, Italy: A longitudinal study. Obesity 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hippel, P.T.; Workman, J. From kindergarten through second grade, U.S. children’s obesity prevalence grows only during summer vacations. Obesity 2016, 24, 2296–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rundle, A.G.; Park, Y.; Herbstman, J.B.; Kinsey, E.W.; Wang, Y.C. COVID-19-related school closings and risk of weight gain among children. Obesity 2020, 28, 1008–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kearns, A.; Whitley, E. Associations of internet access with social integration, wellbeing and physical activity among adults in deprived communities: Evidence from a household survey. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunlap, J.; Barry, H.C. Overcoming exercise barriers in older adults. Physician Sports Med. 1999, 27, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leask, C.F.; Harvey, J.A.; Skelton, D.A.; Chastin, S.F. Exploring the context of sedentary behaviour in older adults (what, where, why, when and with whom). Eur. Rev. Aging Phys. Act. Off. J. Eur. Group Res. Elder. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, M.M. Therapeutic effects of an indoor gardening programme for older people living in nursing homes. J. Clin. Nurs. 2010, 19, 949–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallisy, K.M. Tai Chi beyond balance and fall prevention: Health benefits and its potential role in combatting social isolation in the aging population. Curr. Geri. Rep. 2018, 7, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, S.; D’Ambrosio, L.A.; Felts, A.; Rula, E.Y.; Kell, K.P.; Coughlin, J.F. Reducing isolation and loneliness through membership in a fitness program for older adults: Implications for health. J. Appl. Gerontol. Off. J. South. Gerontol. Soc. 2020, 39, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbins, S.; Hubbard, E.; Flentje, A.; Dawson-Rose, C.; Leutwyler, H. Play provides social connection for older adults with serious mental illness: A grounded theory analysis of a 10-week exergame intervention. Aging Ment. Health 2020, 24, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, N. Falls and fall-prevention in older persons: Geriatrics meets spaceflight! Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.; Bruemmer, V. Exercise as a countermeasure to psycho-physiological deconditioning during long-term confinement. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2010, 42, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malden, S.; Jepson, R.; Laird, Y.; McAteer, J.A. Theory based evaluation of an intervention to promote positive health behaviors and reduce social isolation in people experiencing homelessness. J. Soc. Distress Homeless 2019, 28, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, K.A.; Lord, L.K.; Hill, L.N.; McCune, S. Fostering the human-animal bond for older adults: Challenges and opportunities. Act. Adapt. Aging 2015, 39, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, A.; Nicolle, J. Social isolation and loneliness: The new geriatric giants: Approach for primary care. Can. Fam. Phys. 2020, 66, 176–182. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.; Wang, L.; Siever, J.; Medico, T.D.; Jones, C.A. Loneliness and social isolation among older adults in a community exercise program: A qualitative study. Aging Ment. Health 2019, 23, 736–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinert, E.; Milne-Ives, M.; Surodina, S.; Lam, C. Agile requirements engineering and software planning for a digital health platform to engage the effects of isolation caused by social distancing: Case study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nau, T.; Nolan, G.; Smith, B.J. Enhancing engagement with socially disadvantaged older people in organized physical activity programs. Int. Q. Community Health Educ. 2019, 39, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.G.; Banting, L.; Eime, R.; O’Sullivan, G.; van Uffelen, J.G. The association between social support and physical activity in older adults: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansons, P.; Robins, L.; O’Brien, L.; Haines, T. Gym-based exercise and home-based exercise with telephone support have similar outcomes when used as maintenance programs in adults with chronic health conditions: A randomised trial. J. Physiother. 2017, 63, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murrock, C.J.; Graor, C.H. Depression, social isolation, and the lived experience of dancing in disadvantaged adults. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2016, 30, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, K.; Prybutok, G. A quality mobility program reduces elderly social isolation. Act. Adapt. Aging 2019, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toepoel, V. Ageing, leisure, and social connectedness: How could leisure help reduce social isolation of older people? Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 113, 355–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arlati, S.; Colombo, V.; Spoladore, D.; Greci, L.; Pedroli, E.; Serino, S.; Cipresso, P.; Goulene, K.; Stramba-Badiale, M.; Riva, G.; et al. A social virtual reality-based application for the physical and cognitive training of the elderly at home. Sensors 2019, 19, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.E.; Adair, B.; Ozanne, E.; Kurowski, W.; Miller, K.J.; Pearce, A.J.; Santamaria, N.; Long, M.; Ventura, C.; Said, C.M. Smart technologies to enhance social connectedness in older people who live at home. Australas. J. Ageing 2014, 33, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkner, B.A.; Berg, H.E.; Kozlovskaya, I.; Sayenko, D.; Tesch, P.A. Effects of strength training, using a gravity-independent exercise system, performed during 110 days of simulated space station confinement. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2003, 90, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeln, V.; MacDonald-Nethercott, E.; Piacentini, M.F.; Meeusen, R.; Kleinert, J.; Strueder, H.K.; Schneider, S. Exercise in isolation—A countermeasure for electrocortical, mental and cognitive impairments. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidawi, S.; Trotter, C.; Flynn, C. Prison experiences and psychological distress among older inmates. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2016, 59, 252–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.-M.; Shiroma, E.J.; Lobelo, F.; Puska, P.; Blair, S.N.; Katzmarzyk, P.T. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: An analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet 2012, 380, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammami, A.; Harrabi, B.; Mohr, M.; Krustrup, P. Physical activity and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Specific recommendations for home-based physical training. Manag. Sport Leis. 2020, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S. Can moderate intensity aerobic exercise be an effective and valuable therapy for preventing and controlling the pandemic of COVID-19? Med. Hypotheses 2020, 143, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, C.; Florhaug, J.A.; Franklin, J.; Gottschall, L.; Hrovatin, L.A.; Parker, S.; Doleshal, P.; Dodge, C. A new approach to monitoring exercise training. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2001, 15, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, R.P. COVID-19 and mental health: A review of the existing literature. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 52, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kappen, D.L.; Mirza-Babaei, P.; Nacke, L.E. Older adults’ physical activity and exergames: A systematic review. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2019, 35, 140–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, H.; Bernardino, A.; Sanches, M.; Loureiro, L. Exergames and their benefits in the perception of the quality of life and socialization on institutionalized older adults. In Proceedings of the 5th Experiment International Conference, Funchal, Portugal, 12–14 June 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, A.M.; Kim, M. The exergame as a tool for mental health treatment. J. Creat. Ment. Health 2019, 14, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehfeld, K.; Lüders, A.; Hökelmann, A.; Lessmann, V.; Kaufmann, J.; Brigadski, T.; Müller, P.; Müller, N.G. Dance training is superior to repetitive physical exercise in inducing brain plasticity in the elderly. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douka, S.; Zilidou, V.I.; Lilou, O.; Manou, V. Traditional dance improves the physical fitness and well-being of the elderly. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, J.A.; Smith, P.J.; Hoffman, B.M. Is exercise a viable treatment for depression? Acsm’s Health Fit. J. 2012, 16, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- #HealthyAtHome—Physical Activity. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/campaigns/connecting-the-world-to-combat-coronavirus/healthyathome/healthyathome---physical-activity (accessed on 19 June 2020).

- Guan, H.; Okely, A.D.; Aguilar-Farias, N.; del Cruz, P.B.; Draper, C.E.; el Hamdouchi, A.; Florindo, A.A.; Jáuregui, A.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Kontsevaya, A.; et al. Promoting healthy movement behaviours among children during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 416–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.Á.; Crespo, I.; Olmedillas, H. Exercising in times of COVID-19: What do experts recommend doing within four walls? Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2020, 73, 527–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Li, H. Guidance strategies for online teaching during the COVID-19 epidemic: A case study of the teaching practice of Xinhui Shangya school in Guangdong, China. Sci Insight Edu Front 2020, 5, 547–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Move More Together. Available online: https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/fitness/fitness-basics/move-more-together (accessed on 19 June 2020).

- Make Every Move Count. Available online: https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/fitness/fitness-basics/make-every-move-count-infographic (accessed on 19 June 2020).

- Try the 10-Minute Home Workout. Available online: https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/fitness/getting-active/10-min-home-workout (accessed on 19 June 2020).

- 25 Ways to Get Moving at Home. Available online: https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/fitness/getting-active/25-ways-to-get-moving-at-home-infographic (accessed on 19 June 2020).

- How to Move More Anytime Anywhere. Available online: https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/fitness/getting-active/how-to-move-more-anytime-anywhere (accessed on 19 June 2020).

- Staying Physically Active During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Available online: https://www.acsm.org/read-research/newsroom/news-releases/news-detail/2020/03/16/staying-physically-active-during-covid-19-pandemic (accessed on 26 August 2020).

| Autor andYear | Title | Methods | Results | Practical Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Altena et al. 2020 [25]. | Dealing with sleep problems during home confinement due to the COVID-19 outbreak: Practical recommendations from a task force of the European CBT-I Academy | Summarizing information regarding the confinement and stress-sleep link and insomnia treatment | Stress and possible disruptions of social relationships can be avoided by dealing as with sleep problems. |

|

| Chevance et al. 2020 [26]. | Ensuring mental health care during the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in France: a narrative review | Analyzing the vulnerability of psychiatric patients to COVID-19 based on the existing literature, as well as a description of the procedures during the pandemic in the psychiatry setting. | Reorganizing of French psychiatry and simultaneously dealing with negative effects of home-isolation on mental health. A Major problem is a missing common voice for psychiatry in France to approach health authorities. |

|

| Luzi & Radaelli 2020 [27]. | Influenza and obesity: its odd relationship and the lessons for COVID-19 pandemic | Transferring findings about influenza and obesity for the visible risks of the COVID-19 pandemic. | Suggestions for weight loss in obese individuals with mild caloric restriction, including activators in drug treatment for obesity-diabetes patients and exercise (mild to moderate). Isolation should be longer than in normal weight individuals to reduce the risk of infection in this at-risk population. |

|

| Narici et al. 2020 [28]. | Impact of sedentarism due to the COVID-19 home confinement on neuromuscular, cardiovascular and metabolic health: Physiological and pathophysiological implications and recommendations for physical and nutritional countermeasures | Transferring results from models and real-life scenarios of inactivity to the COVID-19 home confinement. | Even a few days of inactivity and a sedentary lifestyle are enough to induce decreased aerobic capacity, insulin resistance, fat deposition, fiber denervation, neuromuscular junction damage, low-grade systemic inflammation, and muscle loss. Low to medium intensity high volume exercise in regular rhythms, combined with 15–25% caloric intake-reduction have the potential to prevent cardiovascular, metabolic, neuromuscular, and endocrine health. |

|

| Pecanha et al. 2020 [29]. | Social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic can increase physical inactivity and the global burden of cardiovascular disease | Providing an overview of interventions that could counteract a sedentary lifestyle and physical inactivity in cardiac patients and transferring of results to COVID-19. | Public agencies and health care professionals need to act together for the avoidance of premature death related to sedentary lifestyle. Even for patients with stable cardiovascular diseases home-based exercise programs with low to medium, to vigorous intensity exercises are effective and mostly safe. High-risk patients need special advice, which can be supported via telecommunication-services. Additionally, governmental actions need to be executed to reinforce physical activity promotion on a national level. The materials from scientific societies need to especially be disseminated among vulnerable groups (e.g., elderly, high risk patients). |

|

| Pietrobelli et al. 2020 [30]. | Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on lifestyle behaviors in children with obesity living in Verona, Italy: A Longitudinal Study | Analyzing pediatric individuals with obesity in the areas of activity, sleep, and diet behaviors before and during the COVID-19 home-confinement. | During the lockdown fruit intake increased.Sugary drink, red meat, and potato chip intakes increased as well. The time for sports participation decreased, sleep time and screen time increased. It can be assumed that, depending on duration, the pandemic may lead to negative effects on individual adiposity levels in children. |

|

| With Regard to Author’s Topic | With Regard to PA Recommendations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Article | Type Label (Journal) | Type (Our Judgement) | Methodology | Evidence Level | Types of Studies They Reference | Evidence Base | Comments with Regard to the Evidence Base |

| Altena et al. 2020 [25]. | Review | Narrative review | Summarizing literature and making recommendations for the current situation based on theoretical basis. | Level II (paper refers to at least one RCT). | 1 Review; 1 Systematic review and meta-analysis; 1 Clinical trial. | Medium | Proof of effectiveness based on individual reviews and one study. Limited recommendations can be made. |

| Chevance et al. 2020 [26]. | Narrative review | Narrative review | Summarizing literature and transferring results to the current situation. | Level VI (paper refers mostly to descriptive studies and reviews). | 1 Letter to the editor | Weak | Less evidence, only weak recommendation can be made based on the lack of theoretical background. |

| Luzi & Radaelli 2020 [27]. | Narrative review | Narrative review | Summarizing literature and transferring results to the current situation. | Level II (paper refers to at least one well designed RCT). | 1 Epidemiological study | Weak | Less evidence, only one weak recommendation can be made based on the lack of theoretical background. |

| Narici et al. 2020 [28]. | Article | Narrative review | Summarizing literature and making recommendations for the current situation based on theoretical basis. | Level VI (paper refers mostly to descriptive studies and reviews). | 1 Quantitative study; 1 Narrative review | Medium | Proof of effectiveness based on one review and one study. Limited recommendations can be made. |

| Pecanha et al. 2020 [29]. | Review | Narrative review | Summarizing literature and making recommendations for the current situation based on theoretical basis. | Level II (paper refers to seven RCT´s). | 5 RCT´s 1, 2 reviews, 1 crossover trial, 1 cohort study, 3 quantitative studies. | Medium | Proof of effectiveness based on two reviews and five different studies, including three different types. Some recommendations can be made. |

| Pietrobelli et al. 2020 [30]. | Brief cutting-edge report | Qualitative study | Referring to a longitudinal study and adding new questions relevant to the current situation. | Level VI (paper refers to descriptive studies and a review). | Conclusion from their study. | Weak | Less evidence, only weak recommendation can be made based on the lack of theoretical background. |

| Topic | Autor/Year | Title | Contribution for Possible Application in the Pandemic | Type Label (Journal) | Evidence Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design of PA 1 programs | Anderson et al. 2015 [43] | Fostering the Human-Animal Bond for Older Adults: Challenges and Opportunities | Pet ownership has the potential for reducing social isolation and an increase in PA. | Case study | Level VI (paper refers to descriptive and qualitative studies). |

| Dunlap et al. 1999 [34] | Overcoming exercise barriers in older adults | For PA promotion, it is important to explain benefits of exercise, set realistic personal goals, control pain, treat chronic conditions, dispel misunderstandings. | Review article | Level VI (paper refers to descriptive and qualitative studies). | |

| Freedman et al. 2020 [44] | Social isolation and loneliness: the new geriatric giants Approach for primary care | Family doctors are positioned to identify socially isolated older adults and to initiate services. | Clinical review | Level V (paper is not a formal systematic review and does not provide a quantitative but a qualitative synthesis, of the field). | |

| Hwang et al. 2019 [45] | Loneliness and social isolation among older adults in a community exercise programme: a qualitative study | A community exercise program can motivate older adults to reduce their feelings of loneliness. | Qualitative study | Level VI (paper refers mostly to their qualitative study). | |

| Kearns & Whitley 2019 [33] | Associations of internet access with social integration, wellbeing and physical activity among adults in deprived communities: evidence from a household survey | Internet access has the potential to reduce social isolation, reinforce social inequalities, and generate better wellbeing. | Qualitative study | Level VI (paper refers mostly to their qualitative study). | |

| Leask et al. 2015 [35] | Exploring the context of sedentary behavior in older adults (what, where, why, when and with whom) | Interventions in the home environment, which focus on afternoon sitting time are necessary. | Cross-sectional exploratory study | Level VI (paper refers mostly to their qualitative study). | |

| Meinert et al. 2020 [46] | Agile Requirements Engineering and Software Planning for a Digital Health Platform to Engage the Effects of Isolation Caused by Social Distancing: case Study | Digital health platforms can combine societal and mental variables arising from social distancing measures. | Case-study | Level VI (paper refers mostly descriptive and qualitative studies). | |

| Nau et al. 2019 [47] | Enhancing Engagement with Socially Disadvantaged Older People in Organized Physical Activity Programs | A positive socio-cultural environment and the identification of activities of interest are preconditions for socially disadvantaged older people. | Qualitative study | Level VI (paper refers mostly to their qualitative study). | |

| Smith et al. 2017 [48] | The association between social support and physical activity in older adults: a systematic review | Social support, especially from family members, can lead to the performance of more leisure time PA. | Systematic review | Level II (review includes at least three RCTs 2). | |

| Examples of non-digital exercises and PA-Programs | Hallisy 2018 [37] | Tai Chi Beyond Balance and Fall Prevention: Health Benefits and Its Potential Role in Combatting Social Isolation in the Aging Population | Tai Chi exercises can be adapted to a wide variety of skill levels and ages. | Review | Level I (review includes only systematic reviews, meta-analysis and clinical practice guidelines). |

| Jansons et al. 2017 [49] | Gym-based exercise and home-based exercise with telephone support have similar outcomes when used as maintenance programs in adults with chronic health conditions: a randomised trial | Telephone support can have positive effects regarding exercise adherence. | RCT | Level II (evidence is obtained from their own RCT). | |

| Tse 2010 [36] | Therapeutic effects of an indoor gardening programme for older people living in nursing homes | An indoor gardening program can improve life satisfaction and social networking, and also decrease loneliness in older adults. | Quasi-experimental pre and posttest control group study | Level III (evidence is obtained mostly from their controlled trial. | |

| Murrock et al. 2016 [50] | Depression, Social Isolation, and the Lived Experience of Dancing in Disadvantaged Adults | Dancing should be considered for patients with depression and social isolation to develop a sense of belonging. | Qualitative study | Level VI (paper refers to their qualitative study). | |

| Sen et al. 2019 [51] | A Quality Mobility Program Reduces Elderly Social Isolation | A quality mobility program supervised by clinical professionals in a safe environment fosters sustained relationships that improve the quality of life and reduces social isolation in the elderly. | Case study | Level VI (paper refers mostly to their own qualitative study). | |

| Toepoel 2013 [52] | Ageing, Leisure, and Social Connectedness: How could Leisure Help Reduce Social Isolation of Older People? | Sports, cultural activities, voluntary work, holidays, reading books, shopping, and hobbies are found to be successful predictors for social connectedness of older people and friends support in participation in leisure activities. Therefore, local communities can use relationships and develop special programs for generating social connectedness. | Qualitative study | Level VI (paper refers to their own qualitative study). | |

| Digital Health Technologies | Arlati et al. 2019 [53] | A Social Virtual Reality-Based Application for the Physical and Cognitive Training of the Elderly at Home | Virtual reality-based applications can implement the possibility to train with other users, which can reduce the risk of social isolation. | Development study | Level VI (paper refers mostly to descriptive studies). |

| Brady et al. 2020 [38] | Reducing Isolation and Loneliness Through Membership in a Fitness Program for Older Adults: Implications for Health | Members of a digital fitness program increased their physical activity level and reduced social isolation and loneliness. | Cross-sectional, quasi-experimental study | Level III (evidence is obtained from their own controlled trial). | |

| Dobbins et al. 2020 [39] | Play provides social connection for older adults with serious mental illness: A grounded theory analysis of a 10-week exergame intervention | The group-play modus by exergames for older adults with mental illness can increase social belonging and a higher PA level. | Qualitative study | Level VI (paper refers mostly to their qualitative study). | |

| Morris et al. 2014 [54] | Smart technologies to enhance social connectedness in older people who live at home | Assistance to better manage and understand health conditions. Smart technologies (e.g., tailored internet programs) can generate improvements in aspects of social connectedness. | Systematic review | Level II (review includes six RCTs). | |

| Space-Simulation Isolation | Alkner et al. 2003 [55] | Effects of strength training, using a gravity-independent exercise system, performed during 110 days of simulated space station confinement | Resistance training increases performance and maximal force output during long-term confinement. | Controlled study | Level III (evidence is obtained from their own controlled trial). |

| Goswami 2017 [40] | Falls and Fall-Prevention in Older Individuals: Geriatrics Meets Spaceflight! | The comparison of astronauts, which spend large amounts of time in space and follow special exercise training, can be transferred to bed-confined older individuals. | Review | Level II (review includes three RCTs). | |

| Schneider et al. 2010 [41] | Exercise as a countermeasure to psycho-physiological deconditioning during long-term confinement | Exercises are useful to prevent psycho-physiological changes during confinement. | Qualitative study | Level VI (paper refers to their own qualitative study). | |

| Real-Life Isolation | Abeln et al. 2015 [56] | Exercise in isolation—a countermeasure for electrocortical, mental and cognitive impairments | Regularly performed voluntary exercise supports subjective mental well-being of long-term isolated people. | Qualitative study | Level VI (paper refers to their own qualitative study). |

| Malden et al. 2019 [42] | A theory-based evaluation of an intervention to promote positive health behaviors and reduce social isolation in people experiencing homelessness | After participating in the intervention, homeless individuals reported improvements in self-esteem, mental wellbeing, and social interaction. Additionally, their PA level and general health behavior had improved. | Qualitative study | Level VI (paper refers mostly to their qualitative study). | |

| Baidawi et al. 2016 [57] | Prison Experiences and Psychological Distress among Older Inmates | Psychological distress is connected with lower levels of exercise among older inmates. | Qualitative study | Level VI (paper refers to their own qualitative study). |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bentlage, E.; Ammar, A.; How, D.; Ahmed, M.; Trabelsi, K.; Chtourou, H.; Brach, M. Practical Recommendations for Maintaining Active Lifestyle during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6265. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176265

Bentlage E, Ammar A, How D, Ahmed M, Trabelsi K, Chtourou H, Brach M. Practical Recommendations for Maintaining Active Lifestyle during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(17):6265. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176265

Chicago/Turabian StyleBentlage, Ellen, Achraf Ammar, Daniella How, Mona Ahmed, Khaled Trabelsi, Hamdi Chtourou, and Michael Brach. 2020. "Practical Recommendations for Maintaining Active Lifestyle during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Literature Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 17: 6265. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176265

APA StyleBentlage, E., Ammar, A., How, D., Ahmed, M., Trabelsi, K., Chtourou, H., & Brach, M. (2020). Practical Recommendations for Maintaining Active Lifestyle during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(17), 6265. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176265