1. Introduction

Poor growth during the first thousand days leads to negative consequences ranging from decreased immunity to reduced academic performance in adulthood if not corrected early [

1]. During the past two decades, child undernutrition rates have declined considerably due to the prioritization of the nutrition agenda worldwide. More specifically, global stunting rates for children under five decreased from 32.6% to 22.2% between 2010 and 2017 [

2]. However, the reduction in child stunting in sub-Saharan Africa remained slow from 46.1% in 1970 to 40% in 2010 compared to the global reduction rate of 25.1% [

3]. Therefore, the persisting high rates of stunting continue to be a public health concern in sub-Saharan Africa. Stunting rates remain especially high in the East African region where 39% of the children under five were stunted based on data from 2010 to 2016 [

4].

Identifying determinants and addressing constraints related to child stunting are crucial in designing effective nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions and policies needed for progress worldwide. Furthermore, the importance of the underlying factors of stunting may vary across countries and even across regions within a country [

5]. Thus, further investigation of the contributing factors to malnutrition, such as inadequate water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) conditions and their role in child growth faltering is needed. Poor WASH practices have been associated with suboptimal child growth in sub-Saharan populations and globally [

6,

7,

8]; and, improved WASH conditions have been accompanied by better child anthropometrics in several studies [

6,

7,

9,

10,

11,

12].

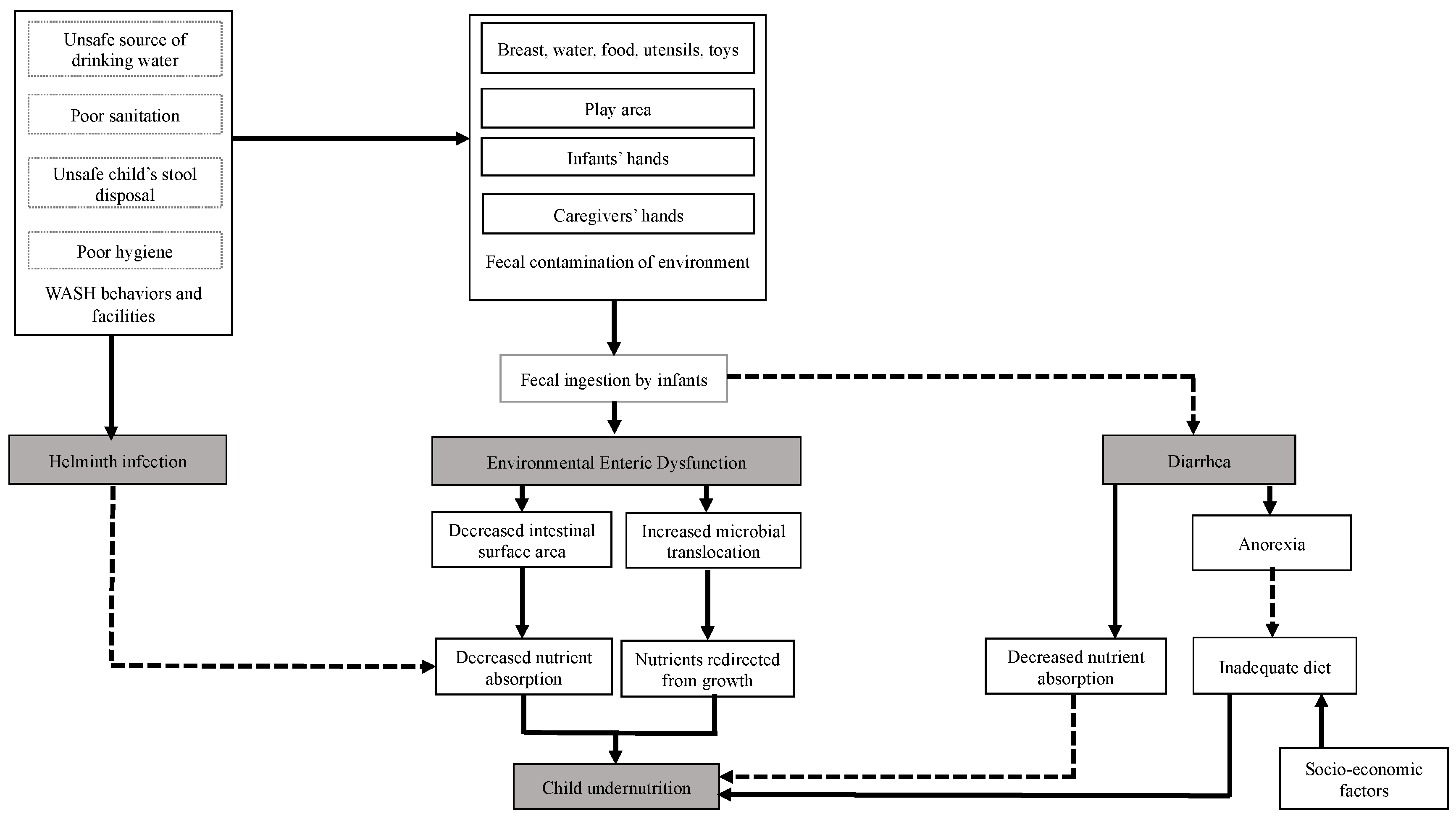

Figure 1 summarizes three pathways suggested to explain the role of unsafe WASH in child stunting. Repeated episodes of diarrhea and chronic helminth infections can reduce nutrient absorption leading to undernutrition [

13,

14]. Additionally, environmental enteric dysfunction (EED), widespread in areas with poor WASH indicators, has been suggested to cause impaired linear growth in children [

15,

16]. A pooled analysis from 140 countries reported that open defecation explained 54% of the height variation in children under the age of five [

9]. Thus, inadequate WASH practices likely contribute to the slow reduction in child stunting rates in sub-Saharan Africa.

However, large cluster randomized trials recently reported no effect of individual or combined WASH interventions on linear growth in children under 5 years [

18]. Moreover, compared to improved nutrition alone, there were no additional benefits of combining better WASH and nutrition on child length. Because of the high levels of pathogens reported from the children’s hands and in the drinking water, the low-cost and household-level WASH implemented in these studies may not have been sufficient to reduce pathogen contamination [

18,

19]. These results suggest that more elaborate and more specific WASH services may be needed to limit pathogen transmission from poor WASH practices. The UNICEF and WHO Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene (JMP) provides criteria for global standardized WASH indicators [

20]. The indicators have been updated to include more detailed specifications, called “ladders”, within each category. These indicators can be used to monitor progress towards safe WASH conditions and in research analyses [

20,

21,

22]. To our knowledge, there are limited studies examining links between WASH assessed with the newly refined JMP indicators and child stunting in the East African region.

To remedy the slow progress towards a reduction in child undernutrition in the region, further investigation of nutrition-sensitive as well as nutrition-specific factors contributing to the high prevalence of stunting in the East African region is critical. Analyzing the associations between the different levels of the JMP indicators and child length provides additional insights on the type of WASH interventions that may contribute most effectively to reducing stunting rates for each country. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the association between WASH conditions and child length in East Africa using nationally representative data. The results from this study can be used to adjust and prioritize future nutrition-sensitive policies and interventions to reduce childstunting in the region.

4. Discussion

Child stunting rates were high in East Africa, ranging from 20.5% in Kenya to 45% in Burundi. A global study using data from 116 countries over a 42-year period reported that underlying determinants of child undernutrition such as access to safe water and sanitation, maternal education, and dietary quality were strong drivers of the observed stunting reduction [

3]. Increasing access to safe sanitation and water, improving child care practices through women’s education and gender equality, and increasing food security were also identified as key priority areas to accelerate stunting reduction, especially in sub-Saharan Africa [

3]. From our results, there is still a need to improve WASH conditions in East Africa despite the progress made during the past decade. Drinking water availability and quality is a high priority need as more than half of the households in the East African region did not have access to an improved source of water or had to walk at least 30 min for water. Water availability can also impact household hygiene practices, which may explain the fact that the majority of the households had handwashing facilities but no water or soap.

Except for Kenya and Tanzania, where safely managed water was associated significantly with higher LAZ, there was no difference between predicted z-scores of children living in households drinking from surface water, unimproved, limited, and basic water supplies versus safely managed water. Improvement of only the quality of drinking water source and access may not be sufficient to have a positive effect on child linear growth in many situations [

18]. In addition to coming from an improved source, water needs to be available on premise without excessive time required for collection as well as being free from microbial contamination [

20].

Ethiopian and Tanzanian children living in households with limited and basic sanitation facilities were predicted to have higher LAZ scores than those living in households practicing open defecation. The high open defecation rates in Ethiopia (36.4%) and in Tanzania (22.2%) may be the basis for this association. Spears (2013) reported that open defecation significantly decreased children’s LAZ in 140 low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) even after controlling for gross domestic product (GDP) and maternal height. These results are similar to those in other LMICs [

11,

12,

25] where poor WASH conditions were associated with shorter child length.

Some evidence indicates that diarrhea and helminth infection due to inadequate WASH contribute to linear growth faltering [

14,

26]. The diarrhea pathway may then explain the association between poor sanitation and lower height in Uganda where diarrhea prevalence was relatively high (32%). However, not as many Ethiopian (16.5%) and Tanzanian (16.2%) children were reported to have diarrhea. Moreover, cumulative diarrhea burden of more than five episodes before a child was 24 months old only explained 25% of the stunted growth in a pooled multi-country analysis [

14]. Perhaps rapid catch-up growth between diarrhea episodes reduces its contribution to stunting [

27].

Currently, EED has been a focus as a primary pathway by which inadequate WASH leads to stunting [

10,

15,

28]. A cohort study conducted in Peru over 35 months showed that children living in households with poor sanitation and water quality were significantly one centimeter shorter than their counterparts with better conditions [

12]. Furthermore, the effect was shown to be independent of diarrhea, suggesting that the decrease in linear growth might be due to a subclinical condition such as EED. Further analysis of our data showed that associations between better water quality and sanitation and higher LAZ scores remained significant after adjusting for diarrhea (

Table S1). Thus, EED is another possible explanatory pathway for the role of suboptimal WASH on linear growth faltering in East African children. Poor WASH conditions lead to prolonged exposure to pathogens resulting in alteration of gut structure and function [

29]. The changes in intestinal morphology, mainly atrophy of the villi and crypt elongation, result in a reduction in the capacity to absorb nutrients [

29]. Decreased intestinal absorption will lead to nutrient deficiencies because the high nutritional needs of infants and young children will not be met, resulting in undernutrition. Additionally, there may be a loss of gut barrier function leading to the translocation of pathogenic agents. These pathogens trigger intestinal and systemic inflammation reactions that will divert nutrient utilization from growth [

30]. Therefore, EED may at least partially explain the less than expected effectiveness of nutrition-specific interventions on stunting in areas with high burden of undernutrition and poor WASH indicators such as in the East African region.

In Rwanda, children living in households with unimproved water source were shorter compared to those with households drinking from surface water. Similarly, children living in households with unimproved sanitation facilities had lower LAZ compared to children with households practicing open defecation in Tanzania. These results may be explained by other factors in line with the multifactorial aspect of stunting. For example, the proportion of children meeting the minimum dietary diversity was the lowest (17.2%) among the children in households drinking from unimproved water JMP ladder compared to the other categories (data not shown). Additionally, the DHS data only provide information on the presence and types of sanitation facilities and whether they were shared with other households, but not if the facilities were being used. Furthermore, the safely managed sanitation category from the JMP sanitation ladder was not included in the analyses due to missing data on safe removal of child excreta from some countries. Thus, the variables used in our study could miss important aspects of the sanitation component of the JMP.

Our results add to the evidence that low-cost basic WASH interventions likely will not be sufficient to prevent the negative effects of suboptimal WASH on linear growth. In most cases, only the highest categories on ladders of water supply and sanitation facilities predicted significantly higher LAZ. Major improvements in WASH conditions are critically needed in each of the countries in East Africa, not only to observe the desired improvements in children’s anthropometrics, but also to reduce the morbidity prevalence for conditions such as diarrhea.

In addition to the safety and accessibility of the water supply already captured by the JMP indicators, other aspects of water quality need to be considered. Safely managed water may be intermittently unavailable to the households at various times, possibly leading to the use of undesirable water sources. Indicators such as the household water insecurity scale (HWISE) incorporate reliability and adequacy of water supply [

31,

32]. Water insecurity, as measured by the HWISE, has been associated with food insecurity in a multi-country study [

33].

To optimize the potential of better sanitation in reducing fecal pathogen contamination, not only improved facilities are needed for each household, but also human feces need to be discarded safely. In addition, as exposure to animal feces has been associated with lower LAZ in children under 2 years old, such fecal exposure needs to be limited as much as possible [

34,

35]. Reduced exposure can be achieved through sanitation interventions at the community level with strong behavior change components. High adherence and safe removal of child feces was achieved in Bangladesh [

36], Kenya [

37], and Zimbabwe [

38] with the provision of materials (scoops, child potty, and improved latrines) combined with frequent home visits by trained hygiene promoters.

In the present study, hygiene indicators were not associated with child length after adjustment with covariates. These results should not challenge the importance of optimal WASH practices in human health in general [

18]. Hygiene practices could not be assessed comprehensively from the available data. The JMP indicators on hygiene only capture the presence of a handwashing station with water and soap, but do not include whether household members frequently and adequately wash their hands to reduce contamination. Collecting and integrating data on handwashing would likely improve assessment of hygiene practices.

The associations between water, sanitation, and hygiene conditions and child length differed by country. Better water quality and availability were important to increased child LAZ in Kenya and Tanzania because the associations remained significant in the models adjusted with sanitation in Kenya and with adjustment of sanitation and hygiene indicators in Tanzania. Kenya (18.1%) and Tanzania (14%) had the highest proportions of households drinking from surface water in East Africa. For Ethiopia, Tanzania and Uganda, ensuring households have improved latrines without sharing with other households appears to be an important predictor for child linear growth. In addition to having the highest proportions of open defecation in East Africa, Ethiopia (45.7%) and Tanzania (78.7%) had among the lowest rates of safe removal of child feces (data not shown).

Thus, because water, sanitation, or hygiene conditions influence child length differently for each country, the priorities for improvement must also be based on the local context. The importance of local context is the major reason that a meta-analysis was not conducted on these data in the present study. With the data from each country analyzed separately, we are able to provide evidence that is more context-specific on the importance of water, sanitation, and hygiene conditions for growth of young children.

Improving water sources, reducing open defecation, and increasing handwashing with soap should be priorities for each country. Success will demand high infrastructure coverage with appropriate and efficient behavioral change components. The Integrated Behavioral Model for Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (IBM-WASH) integrates local contextual, psychosocial, and technological factors across multiple levels that may influence WASH behaviors in low income countries [

39]. Most importantly, sustainability of such projects will require buy-in from the local communities and the various stakeholders. Collaboration of different public and private sectors working in nutrition, public health, agriculture, and education on integrated policies and programs also may give improved and sustained results. Future studies should test the effectiveness of safely managed water supplies and sanitation facilities, and appropriate handwashing practices to improve children’s nutritional status in areas with both high rates of child undernutrition and poor WASH conditions. Because these factors contribute to child growth through different pathways, they must be addressed concurrently to maximize intervention effectiveness.

Though this multi-country study is, to the best of our knowledge, the first in East Africa, some limitations must be acknowledged. First, data were obtained from cross-sectional surveys and therefore, no causality could be inferred from the results. Missing data on handwashing practices did not allow for modeling of the association between hygiene and child growth in Kenya, Rwanda, and Zambia. Moreover, all the limitations associated with survey-based studies should be recognized such as social desirability and recall biases. However, the DHS is widely accepted as high quality nationally representative data and the JMP estimates of WASH indicators for each country are based on these datasets.