Exploring the Perceived Risks and Benefits of Heroin Use among Young People (18–24 Years) in Mauritius: Economic Insights from an Exploratory Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Context

1.2. The Economics of Risky Behaviours

1.3. Aims and Research Questions

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling and Recruitment Procedure

2.2. Data Collection

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Local Market for Illicit Substances

“Marijuana’s high is a normal high. The first time I smoked synthetic, I felt different, the high was stronger. Sometimes you can’t control it. And sometimes when we do it, we don’t take it again for another week. And then one week we want to smoke it again. And then we smoke it again and then perhaps in another two days, we want to do it again. We smoke again and again until we get used to it. And then we do it every day.”BV-P1

Selection Factors

“I didn’t get high enough on weed. I didn’t feel right but when I took the syrup and the pills and all that, I felt better. But afterwards, the syrup and the pills, they became too expensive.”BV-P5

“Well, maybe some three or four years since it has changed, it’s like you don’t… sometimes you get… it’s like now, sometimes you get the good quality, sometimes you get the bad quality. Most of the time, it’s the bad quality.”F-P1

“Well when I first started, we used to share one dose between two of us. And then with time, I started feeling that one dosage between two people wasn’t enough because I couldn’t feel anything. It was like I was normal after I’d taken it. Then we’d take two doses for two people. And then with time, we started taking an eighth (of 1g). Then even that wasn’t enough. Then I’d take an eighth on my own. And eventually I started taking a quarter and with that I could feel it was ok. And when I felt I could take more, I’d add synthetic and take less brown.”BV-P1

3.3. Perceived Benefits of Injecting Drug Use among Young People

3.3.1. Value Addition to Self

“I was fat, as big as my sister. But it was the drugs that sustained me. Without them I think I would already have died. My CD4 had reached level 4. When that happens to people, they usually die.”BC-P1

3.3.2. Value Addition in Dealing with Others

“So a friend would walk past and say, hey, are you going to see a girl? Have something first, smoke something. You’ll be better, your girlfriend will like it. That’s how they are those youngsters. But I don’t find it to be like that. That’s what makes those young people start using. If they have to go see a girl 10 times, they’ll take drugs 10 times. And they’ve become dependent and they’ll start getting sick when they don’t have it.”PL-P2

3.4. Perceived Risks of Injecting Drug Use among Young Users

3.4.1. Threats to Self

“If someone wants to get rid of you without leaving traces, then when you’re injecting, after it’s been cooked, I just need to take one grain of salt and drop it in there. As soon as you inject, you’d die on the spot.”M-P1

“And when we draw it inside the syringe, we have to use a piece of cotton wool. If the cotton wool is dirty or if there’s dust in the syringe, there’s this thing that’s called kongolo, I think you’ve heard of it? This thing that’s called kongolo, you start shaking, you’re cold and then you have a 40 C fever. Your body starts hurting just because of some dust in the needle, you start having all those complications and people can die from this.”M-P1

“That’s also how it is. That’s why with the life that I’m leading it could either be this or that. I either have it or I don’t, it’s either or. But I’d rather not know.”BM-P1

“Yeah, I don’t want her to do it, to have to go on the streets. Because people don’t stand on the streets because they like it. They have to do it because of their addiction.”F-P2

“I told him (the Dr) I had taken drugs and whether it would be a problem with the injection they were giving me. if I didn’t tell him… I had to warn him.”BV-P1

3.4.2. Threats to Others

3.4.3. Threats to Self and Others

“Yeah. And… like people will talk and if your family doesn’t know you’re using and you don’t want them to know. Then you have to hide it.BA-SP3

PL-P2: “Yes, he’s the one I had a child with. It’s like he did everything to make me use again. “

Interviewer: “He was encouraging you to use even when you were pregnant?”

PL-P2: “Yeah, he tried to but I wasn’t too keen; I was scared something would happen to the baby. That he’d be disabled, that’s what I was scared of. That’s why I didn’t say anything about my drug use. I wasn’t even using. That’s all, I was scared.”

4. Discussion

4.1. HR Clients as Heroin Consumers

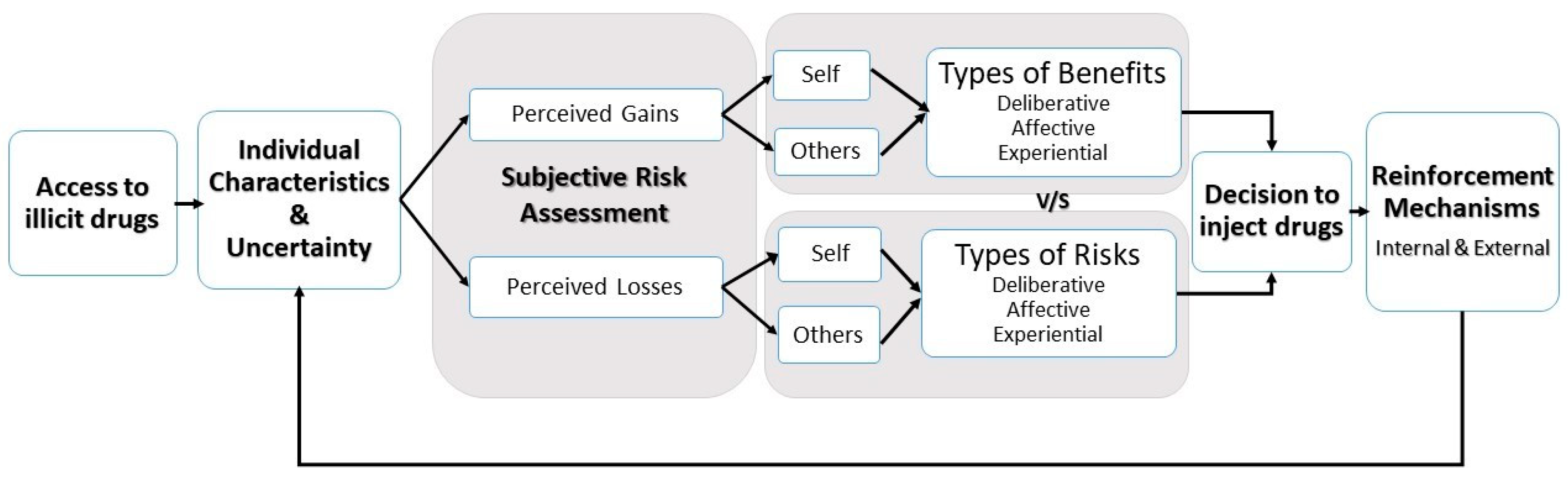

4.2. Uncertainty

4.3. Reinforcing Mechanisms

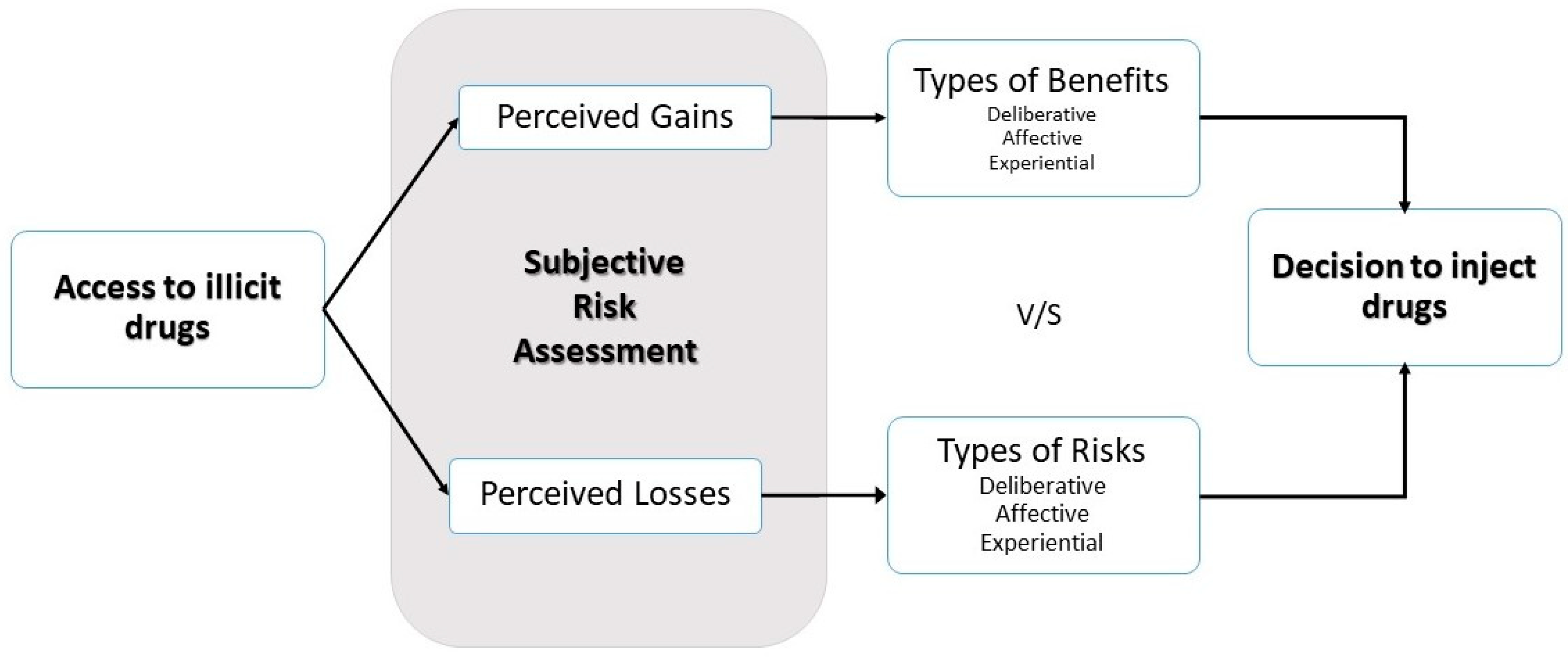

4.4. Towards a Cohesive Model for Injecting Drug Use in Mauritius

5. Limitations and Reflections

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Ministry of Health and Quality of Life. Health Statistics Report 2017. Available online: http://health.govmu.org/English/Statistics/Health/Mauritius/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- Pathack, A.; Saumtally, A.; Kinoo, S.A.H.; Comins, C.; Emmanuel, F. Programmatic mapping to determine the size and dynamics of sex work and injecting drug use in Mauritius. Afr. J. Aids Res. 2018, 17, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health and Quality of Life. National Drug Observatory Report; Ministry of Health and Quality of Life: Port Louis, Mauritius, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Prevention Information et Lutte contre le Sida/Talor Nelson Sofres. Image and Perceptions of Drugs in Mauritius. Available online: http://pils.mu/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/TNS-Image-and-perception-of-drugs-in-Mauritius.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- Ministry of Health and Quality of Life, National AIDS Secretariat. Integrated Biological and Behavioural Surveillance Survey among People Who Inject Drugs 2017: A Respondent Driven Survey (RDS) among People Who Inject Drugs [PWIDs] in the Island of Mauritius. Available online: http://cut.mu/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/IBBS-Survey-report-for-PWIDs-2017.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report 2010 Annex 8.4 Price and Purity. Available online: www.unodc.org›field›8.4_Price_Purity_Opioids.xlsx (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report 2005, Volume 2, Section 7.1: Opiates: Wholesale, Street Prices and Purity Levels. Available online: https://www.unodc.org/pdf/WDR_2005/volume_2_chap7_opiates.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- Ministry of Health and Quality of Life. 2nd National Drug Observatory Report. Available online: http://health.govmu.org/English/Documents/2018/NDO_MOH_FINAL_JOSE_VERSION_05July_2018Brown.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- UNAIDS 2018 Country Data for Mauritius. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/mauritius (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- Ministry of Health & Quality of Life. HIV/AIDS Statistics. Available online: http://health.govmu.org/English/Documents/2018/HIVDec%202017.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- Collectif Urgence Toxida. Internal Monitoring & Evaluation Reports; Collectif Urgence Toxida: Quatre Bornes, Mauritius, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health & Quality of Life. Internal Monitoring & Evaluation Reports; Ministry of Health and Quality of Life: Port Louis, Mauritius, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk. Econometrica 1979, 47, 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caulkins, J.P.; Kleiman, M.A.R. Drugs and Crime. In The Oxford Handbook of Crime and Criminal Justice; Tony, M., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 275–320. [Google Scholar]

- Piore, M.J. Qualitative research: Does it fit in economics? Eur. Manag. Rev. 2006, 3, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, R.; Klein, M.W. Risk Perception and Health Behaviour. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2015, 5, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, T. Risk Theory in Epidemic Times: Sex, Drugs and the Social Organisation of ‘Risk Behaviour’. Sociol. Health Illn. 1997, 19, 208–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, T.; Wagner, K.; Strathdee, S.A.; Shannon, K.; Davidson, P.; Bourgois, P. Structural Violence and Structural Vulnerability Within the Risk Environment: Theoretical and Methodological Perspectives for a Social Epidemiology of HIV Risk Among Injection Drug Users and Sex Workers. In Rethinking Social Epidemiology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 205–230. [Google Scholar]

- Goudie, A.J.; Sumnall, H.R.; Fild, M.; Clayton, H.; Cole, J.C. The effects of price and perceived quality on the behavioural economics of alcohol, amphetamine, cannabis, cocaine, and ecstasy purchases. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007, 89, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Traditions; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine Publishing Company: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Moller, K.; Sandberg, S. Putting a price on drugs: An economic sociological study of price formation in illegal drug markets. Criminology 2019, 57, 289–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report 2018: Drugs and Age Drugs and Associated Issues among Young People and Older People. Available online: https://www.unodc.org/wdr2018/prelaunch/WDR18_Booklet_4_YOUTH.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- Mital, S.; Miles, G.; McLellan-Lemal, E.; Muthui, M.; Needle, R. Heroin Shortage in Coastal Kenya: A Rapid Assessment and Qualitative Analysis of Heroin Users’ Experiences. Int. J. Drug Policy 2016, 30, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garami, J.; Haber, P.; Myers, C.E.; Allen, M.T.; Misiak, B.; Frydecka, D.; Moustafa, A.A. Intolerance of Uncertainty in Opioid Dependency—Relationship With Trait Anxiety and Impulsivity. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciccarone, D.; Ondocsin, J.; Mars, S.G. Heroin Uncertainties: Exploring Users’ Perceptions of Fentanyl-Adulterated and Substituted ‘Heroin’. Int. J. Drug Policy 2017, 46, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prevention Information et Lutte Contre le Sida. The People Living with HIV Stigma Index. Available online: http://pils.mu/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/STIGMA_F.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- Wise, R.A.; Foob, G.G. The Development and Maintenance of Drug Addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology 2014, 39, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roozenab, H.G.; Boulognea, J.J.; van Tulderc, M.V.; van den Brink, W.; De Jong, C.A.J.; MKerkhofa, J.F. A systematic review of the effectiveness of the community reinforcement approach in alcohol, cocaine and opioid addiction. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004, 74, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stengel, C.M.; Marie, F.; Guise, A.; Pouye, M.; Sigrist, M.; Rhodes, T. They accept me, because I was one of them: Formative qualitative research supporting the feasibility of peer-led outreach for people who use drugs in Dakar, Senegal. Harm Reduct. J. 2018, 15, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total | People Who Used Drugs | Service Providers/ Peer Educator |

|---|---|---|

| Of whom | ||

| Men | 11 | 3 |

| Women | 11 | 2 |

| Currently use Heroin (Inject/Smoke) | 19 | 1 |

| Injected Heroin over the past 4 months | 3 | 1 |

| Enrolled on Methadone but injected in the past 2 months | 1 | |

| On codeine but injects occasionally | 1 | |

| Combined Heroin with other substances | 7 | 2 |

| Injected other substances (buprenorphine, Rivotril, amphetamines) | 2 (1 injected both Rivotril and buprenorphine) | 1 |

| Are HIV positive (disclosed during interview) | 2 | 1 |

| Are HCV positive | Undisclosed | Undisclosed |

| Drug | Street Price (Rs) | US Dollars 1 USD = Rs 35 (2017) |

|---|---|---|

| Heroin | 1/8 g at 400 | 11.5 |

| 1 g at 4500 | 128.5 | |

| New Psychoactive Substances | 100 | 2.85 |

| Cough Syrup | Kaffan 150 | 4.3–7.5 |

| Benylin 60 | 1.7 | |

| Benecot 700 | 20 | |

| Phensezyl 1000 | 28.6 | |

| Others may go up to 1500 | 43 | |

| Rivotril | 100 | 2.85 |

| Marijuana | 2000 | 57.1 |

| Methadone | 250–2000 (depending on quantity) | 57.14 |

| Nova, Zamidol, Dramal, Dramazac, Rohypnol | 40–60 a pill, tablets at 400–600 | 11.4–17.1 |

| Illicit Drug Injected | Additional Substances Mentioned | |

|---|---|---|

| Complements | Used as Regulator/to Stop Momentarily | |

| Heroin | Cough Syrup/Codeine | |

| Analgesics (Tramal) | Street methadone | |

| Tranquilizers | ||

| New Psychoactive Substance (Sintetik) | Buprenorphine | |

| Marijuana | ||

| HIV medication | Codeine | |

| Alcohol | ||

| Buprenorphine | Tranquilizer | Codeine |

| Cough Syrup/Codeine | ||

| Analgesics | ||

| Valium | ||

| Rivotril | ||

| Benzodiazepines or Rohypnol | Used with Heroin and others | Buprenorphine |

| Amphetamines (possibly mixed with other unknown substances) | New Psychoactive Substance | Street methadone |

| Major Theme | Analytical Theme | Code | Type of Perceived Benefit | Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Benefits of Injecting Drug Use | Value addition to self | Mood enhancement and increased well-being | Experiential | “Drugs help me express myself. And yet, when I use, it helps me to not think, almost like it allows me to relax.” BC-P1 |

| Better health | “I’ll be frank, ever since I started using, I haven’t been ill. I don’t have fevers, flus; I don’t get any of those.” BA-P2 | |||

| Increased productivity | “But in general when I was using, it gave me more strength to work, I could do twice the amount of work I usually do.” M-P1 | |||

| Lower costs of injecting drug use | Deliberative | “But… they’re too expensive. I didn’t… how to say it… I didn’t have enough money to continue with the pills so I started taking drugs” BV-P5 | ||

| Dealing with trauma | Experiential | “Err… yeah. In a way, yes, when I saw them like that, I thought that my suffering could be allayed with that. That’s what made me do it” M-P1 | ||

| Value addition in dealing with others | Bonding and experimenting | Experiential | “It’s through the psychotropic pills that I started needing it. When we went to birthday parties, I would see loads of it. And friends would say, come let’s smoke, let’s smoke… I don’t drink, you understand, we would sit, ten of us and we’d all smoke, you understand. And there were lots of it… that’s how I developed the craving.” F-P2 | |

| Intimate relationships and sexuality | Deliberative and experiential | “And like, once I got used to it, it was different. It’s like it was better, you understand? When I talked to her, there were lines that came out of my mouth, I could talk, I was on a cloud.” BV-P3 |

| Major Theme | Analytical Theme | Code | Type of Perceived Risk | Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Risks of Injecting Drug Use | Threat to self | Escalating Costs | Experiential | “Yes, it’s more expensive. An eighth costs Rs 500 (USD 14.2) If I take two of those, that’s Rs 1000 (USD 28.5). If I have to take two more, that’s Rs 2000 (USD 57.0)” BV-P1 |

| Peers | “No well… you can’t… to be honest, you can’t… those kinds of people… you can’t. And this also applies to me, you can’t consider people like that as friends” F-P1 | |||

| Injecting practices | “Yeah, sometimes. Where it’s better to inject, like look here in my hand, those veins that look green? Like here? You’re not supposed to inject here, that’s risky. No green veins because they’ll swell, it’ll do…it’s not good.” M-P1 | |||

| Side-effects and infectious disease | “If the person has AIDS and he’s injected and I use the same syringe, his blood is still in there and when I inject myself, I will also get it”. PL-P3 | |||

| Exploitation | “I later found out that I wasn’t the only one he encouraged to inject and then once they were hooked… he did it before with another girl. He had already…. selling the girl… “ F-P3 | |||

| Overdose and polydrug use | Deliberative | “He was inside, sitting and he had already taken pills, he’d had cough syrup, he’d taken a lot of it and was having a good high. Then he injected an eighth of brown and it was too strong. He couldn’t take it.” BV-P1 | ||

| Loss of control | Experiential/ affective/ deliberative | “Well if I do it, I think about the problems I could get. Diseases and what not. But like I said to you, this drug is more powerful than anything else.” F-P1 | ||

| Threat to others | Disposal of syringes | Deliberative | “I prefer to burn it because if you dispose of it in a trashcan, children could find it and hurt themselves.” BC-P1 | |

| Couple/family | Affective | “And then I realised that I couldn’t love drugs more than I love my children, more than I loved the family that I have built.” M-P1 | ||

| Threat to self and others | Stigma and discrimination | Affective/ experiential | “Because when society looks at us, they don’t approve. We can’t find work. Especially if we engage in immoral activities. It’s hard for us.” BC-P1 | |

| Pregnancy | Deliberative/ affective/ experiential | “Yes, I feel ok. The doctor told me the child could be sick. And despite all the precautions I’ve taken, my belly was small. It was small like that (shows belly…) because of the drugs.” BC-P1 | ||

| Law enforcement | Deliberative/ affective/ experiential | “If I go to the caravan to take some syringes and I take them home. What if as I’m taking the old ones back, the police arrest me? That’s a problem as they could charge me.” F-P1 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

White, G.; Luczak, S.E.; Mundia, B.; Goorah, S. Exploring the Perceived Risks and Benefits of Heroin Use among Young People (18–24 Years) in Mauritius: Economic Insights from an Exploratory Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6126. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176126

White G, Luczak SE, Mundia B, Goorah S. Exploring the Perceived Risks and Benefits of Heroin Use among Young People (18–24 Years) in Mauritius: Economic Insights from an Exploratory Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(17):6126. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176126

Chicago/Turabian StyleWhite, Gareth, Susan E. Luczak, Bernard Mundia, and Smita Goorah. 2020. "Exploring the Perceived Risks and Benefits of Heroin Use among Young People (18–24 Years) in Mauritius: Economic Insights from an Exploratory Qualitative Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 17: 6126. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176126

APA StyleWhite, G., Luczak, S. E., Mundia, B., & Goorah, S. (2020). Exploring the Perceived Risks and Benefits of Heroin Use among Young People (18–24 Years) in Mauritius: Economic Insights from an Exploratory Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(17), 6126. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176126