Associations of Self-Efficacy, Optimism, and Empathy with Psychological Health in Healthcare Volunteers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

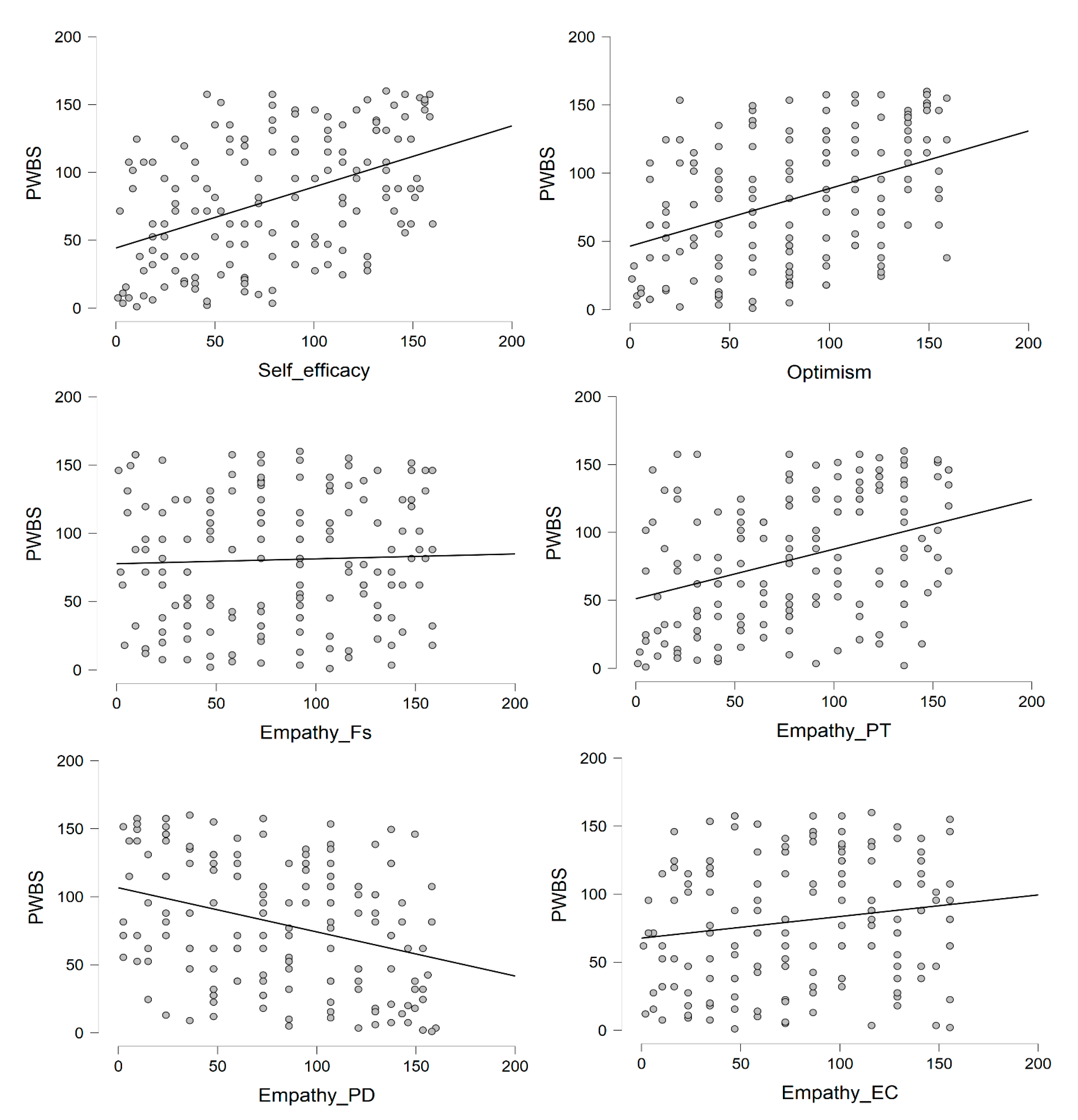

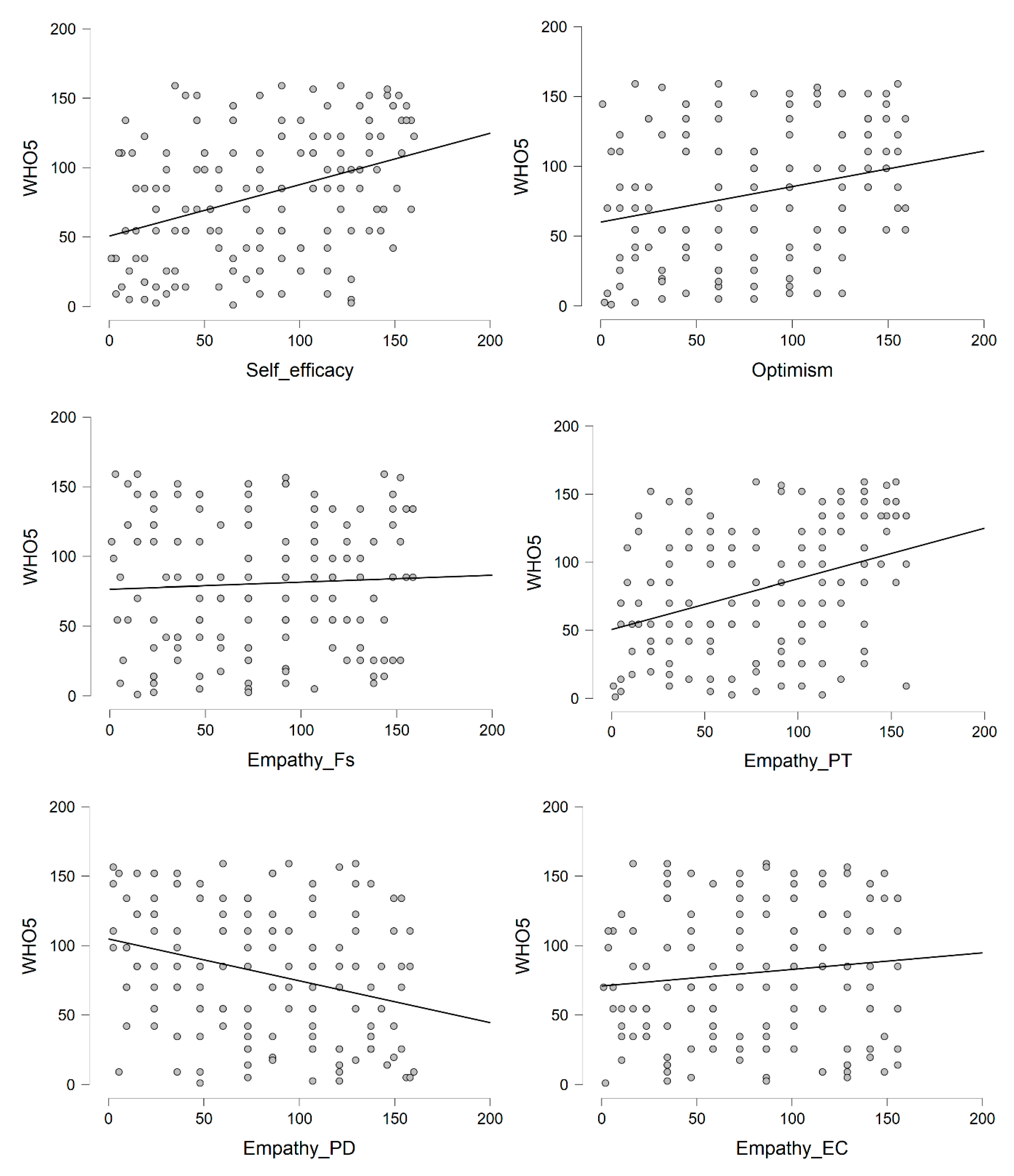

3.1. Preliminary Results

3.2. Regression Models

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Self-efficacy (PPEV) | - | ||||||

| 2. Optimism (LOT-R) | 0.31 *** | - | |||||

| 3. Empathy (IRI-Fs) | 0.09 | 0.18 * | - | ||||

| 4. Empathy (IRI-PT) | 0.43 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.27 *** | - | |||

| 5. Empathy (IRI-EC) | 0.24 ** | 0.17 * | 0.36 *** | 0.31 *** | - | ||

| 6. Empathy (IRI-PD) | −0.45 *** | −0.19 * | 0.09 | −0.27 *** | 0.05 | - | |

| 7. Psychological well-being (PWBS) | 0.49 *** | 0.45 *** | 0.02 | 0.38 *** | 0.15 | −0.38 *** | - |

| 8. Subjective well-being (WHO-5) | 0.37 *** | 0.25 *** | 0.06 | 0.38 *** | 0.10 | −0.30 *** | 0.41 *** |

References

- Salamon, L.M.; Anheier, H.K. Defining the Nonprofit Sector: A Cross-National Analysis; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. In Culture and Politics; Crothers, L., Lockhart, C., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 223–234. [Google Scholar]

- Sridharan, K.; Sivaramakrishnan, G. Therapeutic clowns in pediatrics: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2016, 175, 1353–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Lau, W.Y.; Garg, S.; Lao, J. Effectiveness of pre-operative clown intervention on psychological distress: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2017, 53, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionigi, A.; Flangini, R.; Gremigni, P. Clowns in hospitals. In Humor and Health Promotion; Gremigni, P., Ed.; Nova Science: Hauppage, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 213–227. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J. Volunteerism research: A review essay. Nonprof. Volunt. Sec. Q. 2012, 41, 176–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidee, J.; Vantilborgh, T.; Pepermans, R.; Willems, J.; Jegers, M.; Hofmans, J. Daily motivation of volunteers in healthcare organizations: Relating team inclusion and intrinsic motivation using self-determination theory. Eur. J. Work Org. Psychol. 2017, 26, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.; Chambers, S.K.; Hyde, M.K. Systematic review of motives for episodic volunteering. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprof. Org. 2016, 27, 425–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creaven, A.M.; Healy, A.; Howard, S. Social connectedness and depression: Is there added value in volunteering? J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 2018, 35, 1400–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkinson, C.E.; Dickens, A.P.; Jones, K.; Thompson-Coon, J.; Taylor, R.S.; Rogers, M.; Richards, S.H. Is volunteering a public health intervention? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the health and survival of volunteers. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, A.R.; Nyame-Mensah, A.; De Wit, A.; Handy, F. Volunteering and wellbeing among ageing adults: A longitudinal analysis. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprof. Org. 2019, 30, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N.D.; Samianakis, T.; Kroger, E.; Wagner, L.M.; Dawson, D.R.; Binns, M.A.; Cook, S.L. The benefits associated with volunteering among seniors: A critical review and recommendation for future research. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 1505–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worker, S.M.; Espinoza, D.M.; Kok, C.M.; Go, C.; Miller, J.C. Volunteer outcomes and impact: The contributions and consequences of volunteering in 4-H. J. Youth Dev. 2020, 15, 6–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabassum, F.; Mohan, J.; Smith, P. Association of volunteering with mental well-being: A life course analysis of a national population-based longitudinal study in the UK. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, D.; Ziegelmann, J.P.; Simonson, J.; Tesch-Römer, C.; Huxhold, O. Volunteering and subjective well-being in later adulthood: Is self-efficacy the key? Int. J. Dev. Sci. 2014, 8, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huta, V.; Waterman, A.S. Eudaimonia and its distinction from hedonia: Developing a classifcation and terminology for understanding conceptual and operational defnitions. J. Happiness Stud. 2014, 15, 1425–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Keyes, C.L.M. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Lucas, R. Personality and subjective well-being. In Well-Being: The Foundations of Hedonic Psychology; Kahneman, D., Diener, E., Schwarz, N., Eds.; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Topp, C.W.; Østergaard, S.D.; Søndergaard, S.; Bech, P. The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: A systematic review of the literature. Psychother. Psychosom. 2015, 84, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rand, K.L. Hope, self-efficacy, and optimism: Conceptual and empirical differences. In The Oxford Handbook of Hope; Gallagher, M.W., Lopez, S.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Alessandri, G.; Caprara, G.V.; Tisak, J. The unique contribution of positive orientation to optimal functioning. Eur. Psychol. 2012, 17, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G.V.; Alessandri, G.; Barbaranelli, C. Optimal functioning: Contribution of self-efficacy beliefs to positive orientation. Psychother. Psychosom. 2010, 79, 328–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.E.; Brown, J.D. Positive illusions and well-being revisited: Separating fact from fiction. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 116, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseem, Z.; Khalid, R. Positive thinking in coping with stress and health outcomes: Literature review. J. Res. Reflec. Educ. 2010, 4, 42–61. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, W.; Newcomb, M. Two dimensions of perceived self-efficacy: Cognitive control and behavioral coping ability. In Self-Efficacy: Thought Control of Action; Schwarzer, R., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 39–64. [Google Scholar]

- Schönfeld, P.; Brailovskaia, J.; Zhang, X.C.; Margraf, J. Self-Efficacy as a mechanism linking daily stress to mental health in students: A three-wave cross-lagged study. Psychol. Rep. 2018, 122, 2074–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoji, K.; Cieslak, R.; Smoktunowicz, E.; Rogala, A.; Benight, C.C.; Luszczynska, A. Associations between job burnout and self-efficacy: A meta-analysis. Anxiety Stress Coping 2016, 29, 367–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheier, M.F.; Carver, C.S.; Bridges, M.W. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 67, 1063–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F.; Segerstrom, S.C. Optimism. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 879–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemers, M.M.; Hu, L.T.; Garcia, B.F. Academic self-efficacy and first year college student performance and adjustment. J. Educ. Psychol. 2001, 93, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nes, L.S.; Segerstrom, S.C. Dispositional optimism and coping: A meta-analytic review. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 10, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brissette, I.; Scheier, M.F.; Carver, C.S. The role of optimism in social network development, coping, and psychological adjustment during a life transition. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luszczynska, A.; Scholz, U.; Schwarzer, R. The general self-efficacy scale: Multicultural validation studies. J. Psychol. 2005, 139, 439–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culbertson, S.S.; Fullagar, C.J.; Mills, M.J. Feeling good and doing great: The relationship between psychological capital and well-being. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobel, M.; Tumasjan, A.; Spörrle, M. Be yourself, believe in yourself, and be happy: Self-efficacy as a mediator between personality factors and subjective well-being. Scand. J. Psychol. 2011, 52, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Zeng, P.; Quan, P. The Role of Hope and Self-efficacy on Nurses’ Subjective Well-being. Asia Soc. Sci. 2018, 14, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.; Liang, Y.; An, Y.; Zhao, F. Self-efficacy and psychological well-being of nursing home residents in China: The mediating role of social engagement. Asia Pac. J. Soc. Work 2018, 28, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.; Chun, S.; Lee, S.; Kim, J. Life satisfaction and psychological well-being of older adults with cancer experience: The role of optimism and volunteering. Int. J. Aging Human Dev. 2016, 83, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satici, B. Testing a model of subjective well-being: The roles of optimism, psychological vulnerability, and shyness. Health Psychol. Open 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcon, G.M.; Bowling, N.A.; Khazon, S. Great expectations: A meta-analytic examination of optimism and hope. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2013, 54, 821–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.H. Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 44, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grühn, D.; Rebucal, K.; Diehl, M.; Lumley, M.; Labouvie-Vief, G. Empathy across the adult lifespan: Longitudinal and experience-sampling findings. Emotion 2008, 8, 753–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israelashvili, J.; Karniol, R. Testing alternative models of dispositional empathy: The Affect-to-Cognition (ACM) versus the Cognition-to-Affect (CAM) model. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2018, 121, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teding van Berkhout, E.; Malouff, J.M. The efficacy of empathy training: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Couns. Psychol. 2016, 63, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopik, W.J.; O’Brien, E.; Konrath, S.H. Differences in empathic concern and perspective taking across 63 countries. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2017, 48, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajeh, A.; Baharloo, G.; Soliemani, F. The relationship between psychological well-being and empathy quotient. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2014, 4, 1211–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lee, H.S.; Brennan, P.F.; Daly, B.J. Relationship of empathy to appraisal, depression, life satisfaction, and physical health in informal caregivers of older adults. Res. Nurs. Health 2001, 24, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgault, P.; Lavoie, S.; Paul-Savoie, E.; Grégoire, M.; Michaud, C.; Gosselin, E.; Johnston, C.C. Relationship between empathy and well-being among emergency nurses. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2015, 41, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, J.; Pinto-Gouveia, J.; Cruz, B. Relationships between nurses’ empathy, self-compassion, and dimensions of professional quality of life: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 60, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleichgerrcht, E.; Decety, J. Empathy in clinical practice: How individual dispositions, gender, and experience moderate empathic concern, burnout, and emotional distress in physicians. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C.D.; Shaw, L.L. Evidence for altruism: Toward a pluralism of prosocial motives. Psychol. Inq. 1991, 2, 107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Penner, L.A. Dispositional and organizational influences on sustained volunteerism: An interactionist perspective. J. Soc. Issues 2002, 58, 447–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbaranelli, C.; Capanna, C. Efficacia personale e collettiva nelle associazioni di volontariato socio-assistenziale. In La Valutazione dell’Autoefficacia: Interventi e Contesti Culturali; Caprara, G.V., Ed.; Erickson: Trento, Italy, 2001; pp. 147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Giannini, M.; Schuldberg, D.; Di Fabio, A.; Gargaro, D. Misurare l’ottimismo: Proprietà psicometriche della versione italiana del Life Orientation Test—Revised (LOT-R). Counseling 2008, 1, 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Scheier, M.F.; Carver, C.S. Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychol. 1985, 4, 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albiero, P.; Ingoglia, S.; Lo Coco, A. Contributo all’adattamento italiano dell’Interpersonal Reactivity Index. TPM 2006, 13, 107–125. [Google Scholar]

- Sirigatti, S.; Penzo, I.; Iani, L.; Mazzeschi, A.; Hatalskaja, H.; Giannetti, E.; Stefanile, C. Measurement invariance of Ryff’s psychological well-being scales across Italian and Belarusian students. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 113, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Daukantaité, D.; Zukauskiene, R. Optimism and subjective well-being: Affectivity plays a secondary role in the relationship between optimism and global life satisfaction in the middle-aged women. Longitudinal and cross-cultural findings. J. Happiness Stud. 2012, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krok, D. The mediating role of optimism in the relations between sense of coherence, subjective and psychological well-being among late adolescents. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2015, 85, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N.D.; Lachendro, E. Egocentrism as a source of unrealistic optimism. Pers. Soc. Psychol. B 1982, 8, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plante, C.N.; Reysen, S.; Groves, C.L.; Roberts, S.E.; Gerbasi, K. The Fantasy Engagement Scale: A flexible measure of positive and negative fantasy engagement. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 39, 127–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, C. Helping others helps? A self-determination theory approach on work climate and wellbeing among volunteers. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2019, 14, 1099–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionigi, A. Personality of clown doctors: An exploratory study. J. Individ. Differ. 2016, 37, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bas-Sarmiento, P.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, M.; Baena-Baños, M.; Correro-Bermejo, A.; Soler-Martins, P.S.; de la Torre-Moyano, S. Empathy training in health sciences: A systematic review. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 2020, 44, 102739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N (%) | Mean (SD) | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 102 (63.7) | ||

| Male | 58 (36.3) | ||

| Age | 32.5 (9.5) | 20–60 | |

| Educational level | |||

| Secondary school | 81 (50.6) | ||

| University degree | 79 (49.4) | ||

| Length of experience a, months | 42.4 (28.6) | 1–132 | |

| Previous experience a | |||

| None | 55 (34.4) | ||

| Any | 105 (65.6) |

| Mean (SD) | Range | Cronbach’s | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy (PPEV) | 71.47 (8.82) | 46–92 | 0.86 |

| Optimism (LOT-R) | 16.88 (3.67) | 2–24 | 0.71 |

| Empathy—(IRI-Fs) | 17.38 (5.12) | 1–28 | 0.75 |

| Empathy—(IRI-PT) | 19.20 (4.60) | 7–28 | 0.76 |

| Empathy—(IRI-PD) | 8.98 (4.72) | 0–21 | 0.76 |

| Empathy—(IRI-EC) | 21.34 (3.94) | 9–28 | 0.70 |

| Psychological well-being (PWBS) | 93.91 (11.31) | 61–122 | 0.72 |

| Subjective well-being (WHO-5) | 16.45 (4.48) | 4–25 | 0.83 |

| Outcome Variable | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological Well-Being (PWBS) | Subjective Well-Being (WHO-5) | |||||

| Independent Variable | Adjust. R2 | ΔR2 | β | Adjust. R2 | ΔR2 | β |

| Step 1 | 0.33 *** | 0.15 *** | ||||

| Self-efficacy (PPEV) | 0.39 *** | 0.32 *** | ||||

| Optimism (LOT-R) | 0.33 *** | 0.15 * | ||||

| Step 2 | 0.35 *** | 0.02 * | 0.19 *** | 0.05 ** | ||

| Self-efficacy (PPEV) | 0.33 *** | 0.23 ** | ||||

| Optimism (LOT-R) | 0.30 *** | 0.11 | ||||

| Empathy—(IRI-PT) | 0.16 * | 0.25 ** | ||||

| Step 3 | 0.36 *** | 0.02 * | 0.20 *** | 0.02 | ||

| Self-efficacy (PPEV) | 0.27 *** | 0.18 * | ||||

| Optimism (LOT-R) | 0.29 *** | 0.10 | ||||

| Empathy—(IRI-PT) | 0.14 * | 0.24 ** | ||||

| Empathy—(IRI-PD) | −0.16 * | −0.14 | ||||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dionigi, A.; Casu, G.; Gremigni, P. Associations of Self-Efficacy, Optimism, and Empathy with Psychological Health in Healthcare Volunteers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6001. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17166001

Dionigi A, Casu G, Gremigni P. Associations of Self-Efficacy, Optimism, and Empathy with Psychological Health in Healthcare Volunteers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(16):6001. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17166001

Chicago/Turabian StyleDionigi, Alberto, Giulia Casu, and Paola Gremigni. 2020. "Associations of Self-Efficacy, Optimism, and Empathy with Psychological Health in Healthcare Volunteers" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 16: 6001. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17166001

APA StyleDionigi, A., Casu, G., & Gremigni, P. (2020). Associations of Self-Efficacy, Optimism, and Empathy with Psychological Health in Healthcare Volunteers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 6001. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17166001