“A Woman Is a Puppet.” Women’s Disempowerment and Prenatal Anxiety in Pakistan: A Qualitative Study of Sources, Mitigators, and Coping Strategies for Anxiety in Pregnancy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

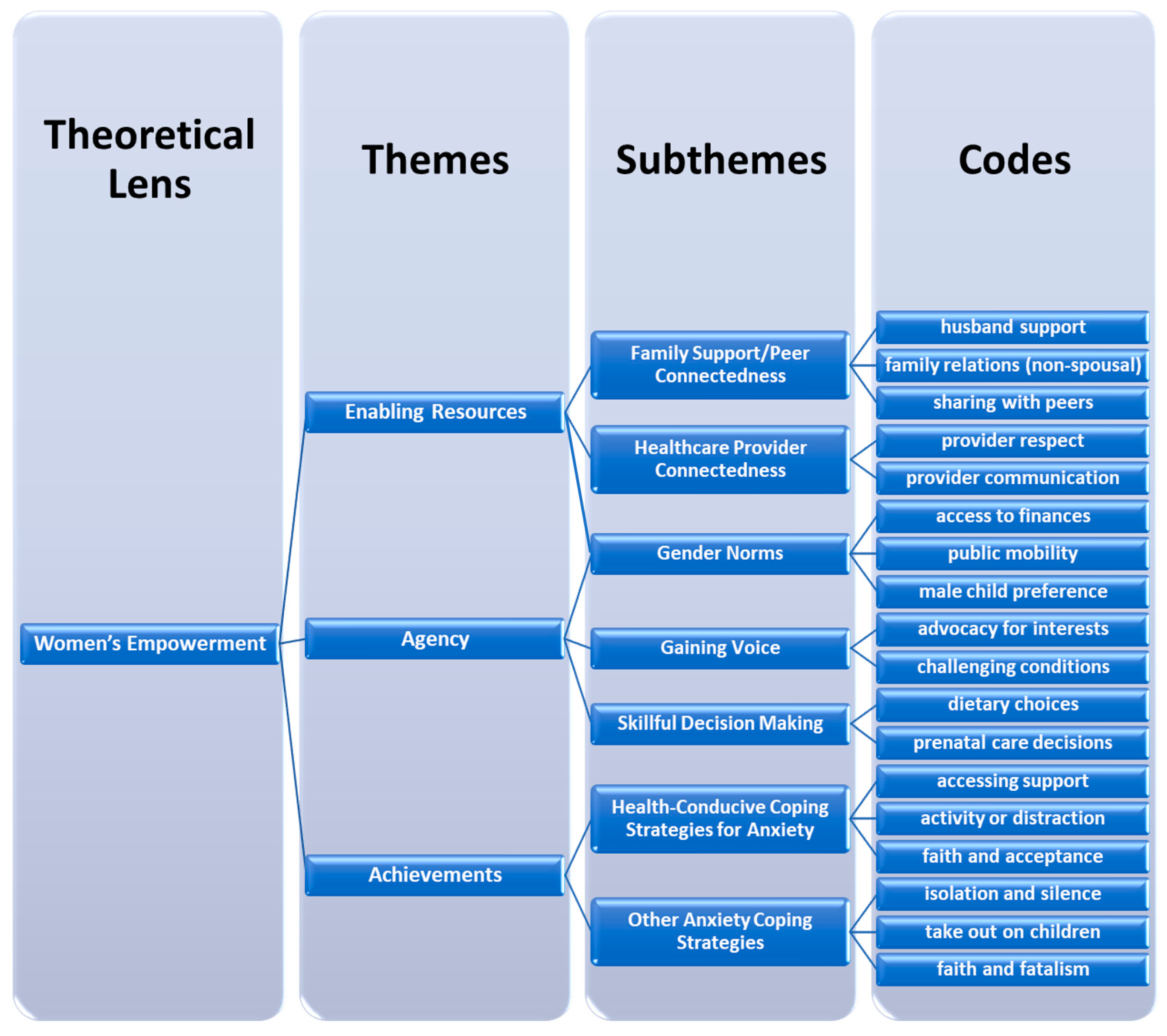

3. Results

3.1. Agency

3.1.1. Gaining Voice

3.1.2. Skillful Decision-Making

3.2. Enabling Resources

3.2.1. Family Support and Peer Connectedness

3.2.2. Healthcare Provider Connectedness

3.3. Gender Norms

3.4. Achievements

3.4.1. Health-Conducive Coping Strategies for Anxiety

3.4.2. Other Coping Strategies for Anxiety

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fisher, J.; Cabral de Mello, M.; Patel, V.; Rahman, A.; Tran, T.; Holton, S.; Holmes, W. Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and lower-middle-income countries: A systematic review. Bull. World Health Organ. 2012, 90, 139H–149H. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, A.; Surkan, P.J.; Cayetano, C.E.; Rwagatare, P.; Dickson, K.E. Grand challenges: Integrating maternal mental health into maternal and child health programmes. PLoS Med. 2013, 10, e1001442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, K.S.; Norris, J.M.; Letourneau, N.L.; King Rosario, M.; Premji, S.S. Prenatal Maternal Anxiety in South Asia: A Rapid Best-Fit Framework Synthesis. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verreault, N.; Da Costa, D.; Marchand, A.; Ireland, K.; Dritsa, M.; Khalifé, S. Rates and risk factors associated with depressive symptoms during pregnancy and with postpartum onset. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 35, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staneva, A.; Bogossian, F.; Pritchard, M.; Wittkowski, A. The effects of maternal depression, anxiety, and perceived stress during pregnancy on preterm birth: A systematic review. Women Birth 2015, 28, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, M.S.; Pana, G.; Premji, S. Prenatal Maternal Anxiety as a Risk Factor for Preterm Birth and the Effects of Heterogeneity on This Relationship: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 8312158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunkel Schetter, C.; Tanner, L. Anxiety, depression and stress in pregnancy: Implications for mothers, children, research, and practice. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2012, 25, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eaton, J.; McCay, L.; Semrau, M.; Chatterjee, S.; Baingana, F.; Araya, R.; Ntulo, C.; Thornicroft, G.; Saxena, S. Scale up of services for mental health in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2011, 378, 1592–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, S.; Thornicroft, G.; Knapp, M.; Whiteford, H. Resources for mental health: Scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. Lancet 2007, 370, 878–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawn, J.E.; Gravett, M.G.; Nunes, T.M.; Rubens, C.E.; Stanton, C.; Group, G.R. Global report on preterm birth and stillbirth (1 of 7): Definitions, description of the burden and opportunities to improve data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2010, 10, S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, C.-L.; Falah-Hassani, K.; Shiri, R. Prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2017, 210, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazi, A.; Fatmi, Z.; Hatcher, J.; Niaz, U.; Aziz, A. Development of a stress scale for pregnant women in the South Asian context: The AZ Stress Scale. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2009, 15, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waqas, A.; Raza, N.; Lodhi, H.W.; Muhammad, Z.; Jamal, M.; Rehman, A. Psychosocial factors of antenatal anxiety and depression in Pakistan: Is social support a mediator? PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0116510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niaz, S.; Izhar, N.; Bhatti, M.R. Anxiety and depression in pregnant women presenting in the OPD of a teaching hospital. Pakistan J. Med. Sci. 2004, 20, 117–119. [Google Scholar]

- Rini, C.K.; Dunkel-Schetter, C.; Wadhwa, P.D.; Sandman, C.A. Psychological adaptation and birth outcomes: The role of personal resources, stress, and sociocultural context in pregnancy. Health Psychol. 1999, 18, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theut, S.K.; Pedersen, F.A.; Zaslow, M.J.; Rabinovich, B.A. Pregnancy subsequent to perinatal loss: Parental anxiety and depression. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1988, 27, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, J.S. The factor structure of the pregnancy anxiety scale. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.S.; Azam, I.S.; Ali, B.S.; Tabbusum, G.; Moin, S.S. Frequency and associated factors for anxiety and depression in pregnant women: A hospital-based cross-sectional study. Sci. World J. 2012, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prost, A.; Lakshminarayana, R.; Nair, N.; Tripathy, P.; Copas, A.; Mahapatra, R.; Rath, S.; Gope, R.K.; Rath, S.; Bajpai, A. Predictors of maternal psychological distress in rural India: A cross-sectional community-based study. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 138, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portela, A.; Santarelli, C. Empowerment of women, men, families and communities: True partners for improving maternal and newborn health. Br. Med. Bull. 2003, 67, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yount, K.M.; Dijkerman, S.; Zureick-Brown, S.; VanderEnde, K.E. Women’s empowerment and generalized anxiety in Minya, Egypt. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 106, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabeer, N. Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Dev. Chang. 1999, 30, 435–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klima, C.S.; Vonderheid, S.C.; Norr, K.F.; Park, C.G. Development of the pregnancy-related empowerment scale. Nurs. Health 2015, 3, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanek, H.; Minault, G. Separate Worlds: Studies of Purdah in South Asia; Chanakya Publications: Delhi, India, 1982; ISBN 0836408322. [Google Scholar]

- Loureiro, M. Debating empowerment: men’s views of women’s access to work in public spaces in Pakistan-administered Kashmir. Contemp. South Asia 2019, 27, 531–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandiyoti, D. Islam and patriarchy: A comparative perspective. In Women in Middle Eastern History: Shifting Boundaries in Sex and Gender; Keddie, N., Baron, B., Eds.; Yale University Press: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Jejeebhoy, S.J.; Sathar, Z.A. Women’s autonomy in India and Pakistan: The influence of religion and region. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2001, 27, 687–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, B.; Bina, A. A Field of One’s Own: Gender and Land Rights in South Asia; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994; Volume 58, ISBN 0521429269. [Google Scholar]

- Pigott, T.A. Gender differences in the epidemiology and treatment of anxiety disorders. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1999, 60 (Suppl 18), 4–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kuehner, C. Gender differences in unipolar depression: An update of epidemiological findings and possible explanations. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2003, 108, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atif, N.; Nazir, H.; Zafar, S.; Chaudhri, R.; Atiq, M.; Mullany, L.C.; Rowther, A.A.; Malik, A.; Surkan, P.J.; Rahman, A. Development of a psychological intervention to address anxiety during pregnancy in a low-income country. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasha, O.; Saleem, S.; Ali, S.; Goudar, S.S.; Garces, A.; Esamai, F.; Patel, A.; Chomba, E.; Althabe, F.; Moore, J.L. Maternal and newborn outcomes in Pakistan compared to other low and middle income countries in the Global Network’s Maternal Newborn Health Registry: An active, community-based, pregnancy surveillance mechanism. Reprod. Health 2015, 12, S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIA South Asia: Pakistan—The World Factbook—Central Intelligence Agency. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/pk.html (accessed on 20 November 2019).

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodani, S.; Zuberi, R.W. Center-based prevalence of anxiety and depression in women of the northern areas of Pakistan. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2000, 50, 138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Qadir, F.; Khalid, A.; Haqqani, S.; Medhin, G. The association of marital relationship and perceived social support with mental health of women in Pakistan. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumford, D.B.; Tareen, I.A.K.; Bajwa, M.A.Z.; Bhatti, M.R.; Karim, R. The translation and evaluation of an Urdu version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1991, 83, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- First, M.B.; Spitzer, R.L.; Gibbon, M.; Williams, J.B.W. User’s Guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders SCID-I: Clinician Version; American Psychiatric Pub: Washington, DC, USA, 1997; ISBN 0880489316. [Google Scholar]

- Pallant, J.F.; Tennant, A. An introduction to the Rasch measurement model: An example using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 46, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinhoven, P.H.; Ormel, J.; Sloekers, P.P.A.; Kempen, G.; Speckens, A.E.M.; Van Hemert, A.M. A validation study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in different groups of Dutch subjects. Psychol. Med. 1997, 27, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015; ISBN 1473943590. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prata, N.; Tavrow, P.; Upadhyay, U. Women’s empowerment related to pregnancy and childbirth: Introduction to special issue. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazi, A.; Fatmi, Z.; Hatcher, J.; Kadir, M.M.; Niaz, U.; Wasserman, G.A. Social environment and depression among pregnant women in urban areas of Pakistan: Importance of social relations. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 63, 1466–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, Z.; Salway, S.M. Gender, pregnancy and the uptake of antenatal care services in Pakistan. Sociol. Health Illn. 2007, 29, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathar, Z.A.; Kazi, S. Women’s autonomy, livelihood and fertility: A study of rural Punjab. In Women’s Autonomy, Livelihood and Fertility: A Study of Rural Punjab; Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE): Islamabad, Pakistan, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, C.Y.; Lee, A.M.; Lam, S.K.; Lee, C.P.; Leung, K.Y.; Koh, Y.W.; Tang, C.S.K. Antenatal anxiety in the first trimester: Risk factors and effects on anxiety and depression in the third trimester and 6-week postpartum. Open J. Psychiatry 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mubarak, A.R. A comparative study on family, social supports and mental health of rural and urban Malay women. Med. J. Malays. 1997, 52, 274–284. [Google Scholar]

- Norbeck, J.S.; Anderson, N.J. Life stress, social support, and anxiety in mid-and late-pregnancy among low income women. Res. Nurs. Health 1989, 12, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Iqbal, Z.; Harrington, R. Life events, social support and depression in childbirth: Perspectives from a rural community in the developing world. Psychol. Med. 2003, 33, 1161–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, C.C.G.; Jomeen, J.; Hayter, M. The impact of peer support in the context of perinatal mental illness: A meta-ethnography. Midwifery 2014, 30, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, N.S.; Ali, B.S.; Azam, I.S. Post partum anxiety and depression in peri-urban communities of Karachi, Pakistan: A quasi-experimental study. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmaliani, R.; Asad, N.; Bann, C.M.; Moss, N.; Mcclure, E.M.; Pasha, O.; Wright, L.L.; Goldenberg, R.L. Prevalence of anxiety, depression and associated factors among pregnant women of Hyderabad, Pakistan. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2009, 55, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, B.T.; Hatcher, J. Health seeking behaviour and health service utilization in Pakistan: Challenging the policy makers. J. Public Health 2004, 27, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, T.; Moore, M. On kinship structure, female autonomy, and demographic behavior in India. Popul. Dev. Rev. 1983, 9, 35–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, Z.; Salway, S. ‘I never go anywhere’: Extricating the links between women’s mobility and uptake of reproductive health services in Pakistan. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 60, 1751–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, C.; Frankel, S.; Smith, G.D. The limits of lifestyle: Re-assessing ‘fatalism’in the popular culture of illness prevention. Soc. Sci. Med. 1992, 34, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanz, K.; Rimer, B.K.; Viswanath, K. Theory, Research, and Practice in Health Behavior and Health Education; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008; ISBN 0787996149. [Google Scholar]

- Smedley, B.D.; Syme, S.L. Promoting health: Intervention strategies from social and behavioral research. Am. J. Health Promot. 2001, 15, 149–166. [Google Scholar]

- Drew, E.M.; Schoenberg, N.E. Deconstructing fatalism: Ethnographic perspectives on women’s decision making about cancer prevention and treatment. Med. Anthropol. Q. 2011, 25, 164–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straughan, P.T.; Seow, A. Fatalism reconceptualized: A concept to predict health screening behavior. J. Gend. Cult. Health 1998, 3, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surkan, P.J.; Hamdani, S.U.; Huma, Z.; Nazir, H.; Atif, N.; Rowther, A.A.; Chaudhri, R.; Zafar, S.; Mullany, L.C.; Malik, A.; et al. Cognitive–behavioral therapy-based intervention to treat symptoms of anxiety in pregnancy in a prenatal clinic using non-specialist providers in Pakistan: Design of a randomised trial. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e037590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, H.R. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2017; ISBN 1442268867. [Google Scholar]

- Mattingly, C.; Garro, L.C. Narrative and the Cultural Construction of Illness and Healing; Univ of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2000; ISBN 0520218256. [Google Scholar]

- Husain, N.; Rahman, A.; Husain, M.; Khan, S.M.; Vyas, A.; Tomenson, B.; Cruickshank, K.J. Detecting depression in pregnancy: Validation of EPDS in British Pakistani mothers. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2014, 16, 1085–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clifford, C.; Day, A.; Cox, J.; Werrett, J. A cross-cultural analysis of the use of the Edinburgh Post-Natal Depression Scale (EPDS) in health visiting practice. J. Adv. Nurs. 1999, 30, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biaggi, A.; Conroy, S.; Pawlby, S.; Pariante, C.M. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 191, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atif, N.; Krishna, R.N.; Sikander, S.; Lazarus, A.; Nisar, A.; Ahmad, I.; Raman, R.; Fuhr, D.C.; Patel, V.; Rahman, A. Mother-to-mother therapy in India and Pakistan: Adaptation and feasibility evaluation of the peer-delivered Thinking Healthy Programme. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flory, J.D.; Yehuda, R. Comorbidity between post-traumatic stress disorder and major depressive disorder: Alternative explanations and treatment considerations. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2015, 17, 141. [Google Scholar]

- Nazneen, S.; Hossain, N.; Chopra, D. Introduction: Contentious women’s empowerment in South Asia. Contemp. South Asia 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, C.L.; Klima, C.S.; Leshabari, S.C.; Steffen, A.D.; Pauls, H.; McGown, M.; Norr, K.F. Randomized controlled pilot of a group antenatal care model and the sociodemographic factors associated with pregnancy-related empowerment in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Number | Item Text (in English) |

|---|---|

| 1 | I feel tense or “wound up.” |

| 3 | I get a sort of frightened feeling as if something awful is about to happen. |

| 5 | Worrying thoughts go through my mind. |

| 7 | I can sit at ease and feel relaxed. * |

| 9 | I get a sort of frightened feeling like butterflies in my stomach. |

| 11 | I feel restless, as if I have to be on the move. |

| 13 | I get a sudden feeling of panic. |

| Interviewee (Pseudonym) | Age (in years) | Number/Gender of Live Children | Marital Status | Length of Education | Family Structure | Other Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 (Erum) | 24 | 1 (girl) | Married | 10 years | Nuclear | |

| M2 (Basma) | 28 | 3 (1 boy, 2 girls) | Married | 12 years | Nuclear | |

| M3 (Pashmina) | 21 | 0 | Married | 12 years | Joint | First pregnancy, recent death of mother-in-law |

| M4 (Tasleem) | 30 | 2 (2 girls) | Married | 12 years | Joint | One boy died in delivery |

| M5 (Teena) | 26 | 0 | Married | 10 years | Joint | |

| M6 (Sobia) | 33 | 0 | Married | 10 years | Nuclear | Two prior miscarriages |

| M7 (Jumana) | 24 | 2 (1 boy, 1 girl) | Married | 5 years | Joint | <2 yeargap with previous pregnancy |

| M8 (Chaandni) | 18 | 0 | Married | 5 years | Joint | Second trimester, 1st pregnancy |

| M9 (Hawa) | 24 | 2 | Married | 10 years | Joint | |

| M10 (Khadija) | 24 | 2 (2 sons) | Married | 5 years | Nuclear | One prior miscarriage and three infants who died post-delivery |

| M11 (Deena) | 23 | 0 | Married | 14 years | Joint | |

| M12 (Zulekha) | 24 | 0 | Married | 6 years | Joint | |

| M13 (Raabia) | 37 | 1 (boy) | Married | 10 years | Joint | Husband’s job abroad |

| M14 (Zara) | 20 | 2 | Married | 5 years | Nuclear | |

| M15 (Saaliha) | 27 | 1 (girl) | Married | 16 years | Joint | Employed as tutor; husband’s job abroad |

| M16 (Shafaq) | 32 | 0 | Married | 14 years | Joint | |

| M17 (Taahira) | 21 | 0 | Married | 12 years | Joint | |

| M18 (Zahirah) | 34 | 4 | Married | 14 years | Nuclear | |

| M19 (Aaliya) | 25 | 0 | Married | 10 years | Joint |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rowther, A.A.; Kazi, A.K.; Nazir, H.; Atiq, M.; Atif, N.; Rauf, N.; Malik, A.; Surkan, P.J. “A Woman Is a Puppet.” Women’s Disempowerment and Prenatal Anxiety in Pakistan: A Qualitative Study of Sources, Mitigators, and Coping Strategies for Anxiety in Pregnancy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4926. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17144926

Rowther AA, Kazi AK, Nazir H, Atiq M, Atif N, Rauf N, Malik A, Surkan PJ. “A Woman Is a Puppet.” Women’s Disempowerment and Prenatal Anxiety in Pakistan: A Qualitative Study of Sources, Mitigators, and Coping Strategies for Anxiety in Pregnancy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(14):4926. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17144926

Chicago/Turabian StyleRowther, Armaan A, Asiya K Kazi, Huma Nazir, Maria Atiq, Najia Atif, Nida Rauf, Abid Malik, and Pamela J Surkan. 2020. "“A Woman Is a Puppet.” Women’s Disempowerment and Prenatal Anxiety in Pakistan: A Qualitative Study of Sources, Mitigators, and Coping Strategies for Anxiety in Pregnancy" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 14: 4926. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17144926

APA StyleRowther, A. A., Kazi, A. K., Nazir, H., Atiq, M., Atif, N., Rauf, N., Malik, A., & Surkan, P. J. (2020). “A Woman Is a Puppet.” Women’s Disempowerment and Prenatal Anxiety in Pakistan: A Qualitative Study of Sources, Mitigators, and Coping Strategies for Anxiety in Pregnancy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(14), 4926. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17144926