The Relationship between Psychological Well-Being and Psychosocial Factors in University Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Psychological Well-Being

1.2. Psychosocial Factors

1.3. Research Hypothesis

1.4. Aims

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Instruments

2.3.1. Psychological Well-Being

2.3.2. Learning Styles and Methodologies

2.3.3. Social Skills

2.3.4. Emotional Intelligence

2.3.5. Anxiety

2.3.6. Empathy

2.3.7. Self-Concept

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Sample Size

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Sample

3.2. Confounding Variables for Psychological Well-Being

3.3. The Correlation between the Psychological Well-Being Dimensions and Psychosocial Factors

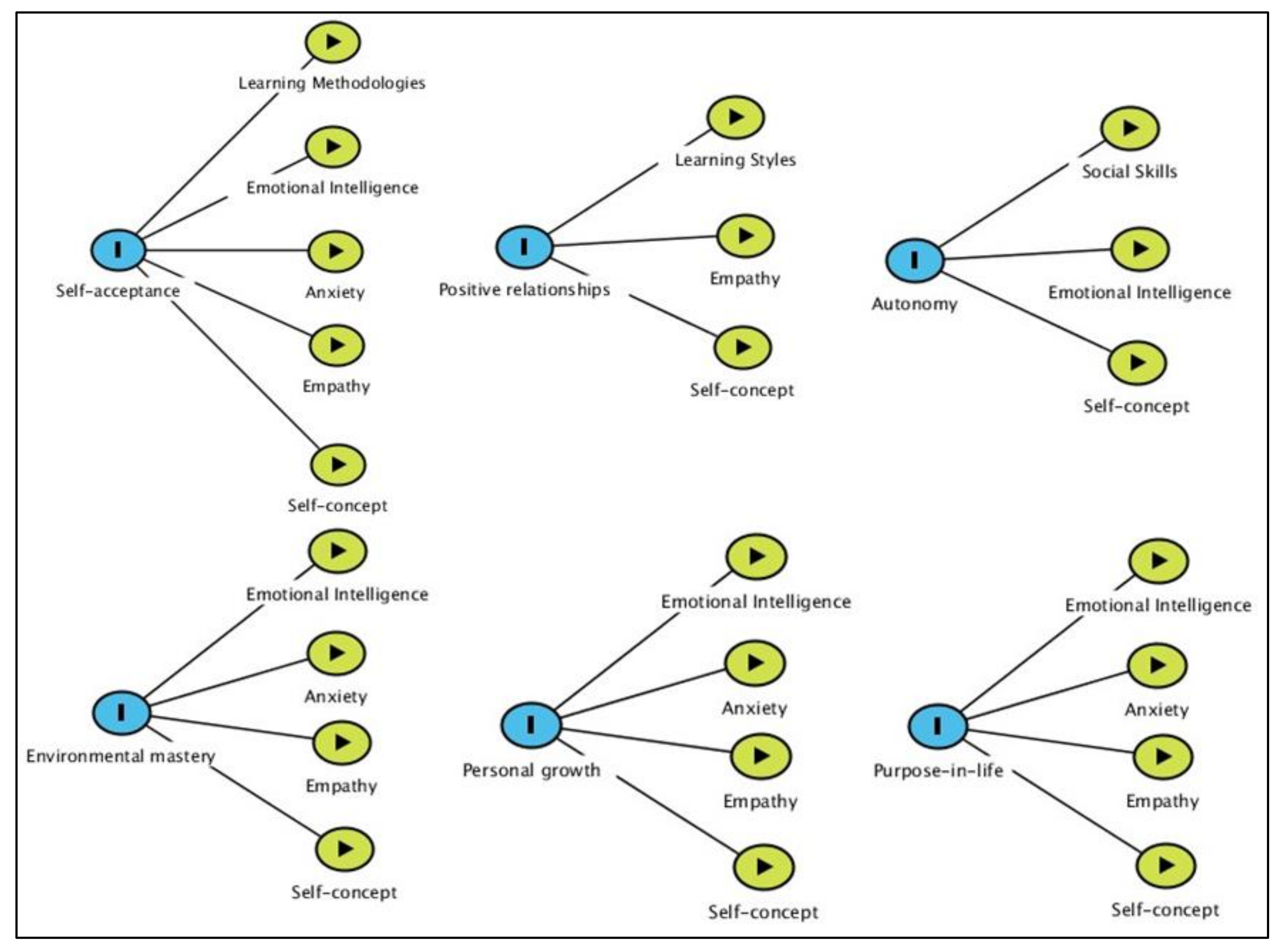

3.4. Influence of Psychosocial Factors on Psychological Well-Being in University Students

4. Discussion

4.1. Learning Styles

4.2. Social Skills

4.3. Emotional Intelligence

4.4. Anxiety

4.5. Empathy

4.6. Self-Concept

4.7. Limitations

4.8. Future Research

4.9. Implications for Education

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ryff, C.D. Psychological Well-Being in Adult Life. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1995, 4, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, D.; Rodríguez-Carvajal, R.; Blanco, A.; Moreno-Jiménez, B.; Gallardo, I.; Valle, C. Adaptación española de las escalas de bienestar psicológico de Ryff [Spanish adaptation of the Psychological Well-Being Scales (PWBS)]. Psicothema 2006, 18, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cooke, R.; Bewick, B.M.; Barkham, M.; Bradley, M.; Audin, K. Measuring, monitoring and managing the psychological well-being of first year university students. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2006, 34, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañero, M.; Mónaco, E.; Montoya, I. La inteligencia emocional y la empatía como factores predictores del bienestar subjetivo en estudiantes universitarios [Emotional intelligence and empathy as predictors of subjective well-being in university students]. Eur. J. Investig. Heal. Psychol. Educ. 2019, 9, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallman, H.M. Psychological distress in university students: A comparison with general population data. Aust. Psychol. 2010, 45, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Alandete, J. Bienestar psicológico, edad y género en universitarios españoles [Psychological well-being, age, and, gender among Spanish undergraduates]. Salud Soc. 2013, 4, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, S.; Dorner, A.; Véliz, A. Bienestar psicológico en estudiantes de carreras de la salud [Psychological well-being of students taking health degree courses]. Investig. en Educ. Médica 2017, 6, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). The Definition and Selection of Key Competencies: Executive Summary; 2005; Available online: http://www.oecd.org/pisa/35070367.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2018).

- Castañeda, J. Análisis del desarrollo de los nuevos títulos de Grado basados en competencias y adaptados al Espacio Europeo de Educación Superior (EEES) [New educational Degree programs based on competences and adapted to the European Higher Education Area (EHEA)]. Redu 2016, 14, 135–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belaunzaran, J. EuroPsy: Un modelo basado en competencias. ¿Es aplicable a la formación sanitaria especializada en Psicología Clínica? [EuroPsy: A competency-based model. Is this model applicable to specialised health training in clinical psychology?]. Educ. Médica 2019, 20, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goleman, D. Emotional Intelligence; Bantam: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, J.D.; Salovey, P.; Caruso, D.R. “Models of emotional intelligence”. In Handbook of Human Intelligence; Sternberg, R.J., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; pp. 396–420. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-On, R. The bar-on model of emotional-social intelligence (esi). Psicothema 2006, 18, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Salovey, P.; Mayer, J.D. Emotional Intelligence. Imagin. Cogn. Pers. 1990, 9, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisquerra, R. Educación Emocional y Bienestar; [Emotional education and well-being]; Praxis: Barcelona, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bisquerra, R.; Pérez-Escoda, N. Las competencias emocionales [Emotional competencies]. Educ. XXI 2007, 10, 61–82. [Google Scholar]

- Bisquerra, R. Psicopedagogía de las Emociones; [Psychopedagogy of emotions]; Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Extremera, N.; Durán, A.; Rey, L. The moderating effect of trait meta-mood and perceived stress on life satisfaction. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2009, 47, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augusto-Landa, J.M.; López-Zafra, E.; Pulido-Martos, M. Inteligencia emocional percibida y estrategias de afrontamiento al estrés en profesores de enseñanza primaria: Propuesta de un modelo explicativo con ecuaciones estructurales (SEM) [Perceived emotional intelligence and stress coping strategies in primary: Proposal for an explanatory model with structural equation modelling (SEM)]. Rev. Psicol. Soc. 2011, 26, 413–425. [Google Scholar]

- Tiana, A. Análisis de las competencias básicas como núcleo curricular en la educación obligatoria española [Analysis of the key competencies as core curriculum of the compulsory education in Spain]. Bordón 2011, 63, 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Atienza, F.M. Autoestima, Inteligencia Emocional, Motivación y Bienestar Psicológico de los Estudiantes de la Universidad de las Palmas de Gran Canaria [Self-Esteem, Emotional Intelligence, Motivation and Psychological Well-Being of the Students of The Univ.]. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Gran Canaria, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pulido-Martos, M.; Augusto-Landa, J.M.; Lopez-Zafra, E. Estudiantes de Enfermería en prácticas clínicas: El rol de la inteligencia emocional en los estresores ocupacionales y bienestar psicológico [Nursing Students in their clinical practice: The role of emotional intelligence on occupational stressors and pychological well-being]. Index Enferm. 2016, 25, 215–219. [Google Scholar]

- Di Lorenzo, R.; Venturelli, G.; Spiga, G.; Ferri, P. Emotional intelligence, empathy and alexithymia: A cross-sectional survey on emotional competence in a group of nursing students. Acta Bio Medica Atenei Parm. 2019, 90 (Suppl. 4), 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrides, K.V.; Furnham, A.; Mavroveli, S. Trait emotional intelligence: Moving forward in the field of EI. In Emotional Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns (Series in Affective Science); Zeidner, G., Roberts, T., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, C.M.; Gallego, D.J.; Honey, P. Los Estilos de Aprendizage: Procedimientos de Diagnóstico y Mejora; [Learning styles: Diagnostic and improvement procedures Learning styles: Diagnostic and improvement procedures]; Messenger Editions: Bilbao, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- García-Ruiz, M.R.; González Fernández, N. El aprendizaje cooperativo en la universidad. valoración de los estudiantes respecto a su potencialidad para desarrollar competencias [Cooperative learning at university. Assessment of students regarding its potential to develop skills]. RIDE Rev. Iberoam. para la Investig. y el Desarro. Educ. 2013, 4, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gündoğar, D.; Gül, S.S.; Uskun, E.; Demirci, S.; Keçeci, D. Üniversite Öðrencilerinde Yaşam Doyumunu Yordayan Etkenlerin İncelenmesi [Investigation of the predictors of life satisfaction in university students]. Klin. Psikiyatr. 2007, 10, 14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Toribay Betancor, A.; Muñoz de Bustillo Díaz, M.; Hernández Jorge, C. Los estudiantes universitarios de carreras asistenciales: Qué habilidades interpersonales dominan y cuáles creen necesarias para su futuro profesional [University students from care disciplines: Which interpersonal skills are stronger and which ones do they think are necessary for their professional future]. Aula Abierta 2001, 78, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Edel, R. El Desarrollo de Habilidades Sociales: ¿Determinan el Éxito Académico? [The Development of Social Skills: Do They Determine Academic Success?]; Red Científica: Lima, Peru, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Vasilenko, E.A.; Vorozheykina, A.V.; GnatyShina, E.V.; Zhabakova, T.V.; Salavatulina, L.R. Psychological factors influencing social adaptation of first-years students to the conditions of university. J. Environ. Treat. Tech. 2020, 8, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilescu, R.; Barna, C.; Epure, M.; Baicu, C. Developing university social responsibility: A model for the challenges of the new civil society. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2010, 2, 4177–4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Juslin, H. Values and Corporate Social Responsibility Perceptions of Chinese University Students. J. Acad. Ethics 2012, 10, 57–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.D.; Salovey, P.; Caruso, D.R.; Cherkasskiy, L. Emotional intelligence. In The Cambridge Handbook of Intelligence; Sternberg, R.J., Kaufman, S.B., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 528–549. [Google Scholar]

- Brackett, M.A.; Rivers, S.E.; Salovey, P. Emotional intelligence: Implications for personal, social, academic, and workplace success. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2011, 5, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, K.J.; Qualter, P. Factor structure, measurement invariance and structural invariance of the MSCEIT V2.0. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2011, 51, 492–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidner, M.; Roberts, R.D.; Matthews, G. The science of emotional intelligence: Current consensus and controversies. Eur. Psychol. 2008, 13, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, N.; Castejón, J.L. La inteligencia emocional como predictor del rendimiento académico en estudiantes universitarios [Emotional intelligence as predictor of academic achievement in university students]. Ansiedad y Estrés 2006, 13, 121–131. [Google Scholar]

- López-Pérez, B.; Fernández-Pinto, I. TECA: Test de Empatía Cognitiva y Afectiva [TECA: Cognitive and Affective Empathy Test]; TEA Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Warden, D.; Mackinnon, S. Prosocial children, bullies and victims: An investigation of their sociometric status, empathy and social problem-solving strategies. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2003, 21, 367–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaigordobil, M.; De Galdeano, P.G. Empatía en niños de 10 a 12 años [Empathy in children aged 10 to 12 years]. Psicothema 2006, 18, 180–186. [Google Scholar]

- Gustems Carnicer, J.; Calderón, C. Empatía y estrategías de afrontamiento como predictores del bienestar en estudiantes universitarios españoles [Empathy and coping strategies as predictors of well-being in Spanish university students]. Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 12, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, C.; Andreu, Y. Inteligencia emocional percibida, bienestar subjetivo, estrés percibido, engagement y rendimiento académico en adolescentes [Perceived emotional intelligence, subjective well-being, perceived stress, engagement and academic achievement of adolescents]. Rev. Psicodidact. J. Psychodidactics 2016, 21, 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.; Kaur, R. Study of emotional intelligence in association with subjective well-being among. Indian J. Heal. Wellbeing 2018, 9, 122–124. [Google Scholar]

- Shavelson, R.J.; Hubner, J.J.; Stanton, G.C. Self-Concept: Validation of construct interpretations. Rev. Educ. Res. 1976, 46, 407–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillén-García, F.; Ramírez-Gómez, M. Relación entre el autoconcepto y la condición física en alumnos del Tercer Ciclo de Primaria [Relationship between self-concept and the physical fitness of third-cycle primary school students]. Rev. Psicol. Deport. 2011, 20, 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Mruk, C.J. Self-esteem Research, Theory and Practice: Toward a Positive Psychology of Self Esteem; Springer Publishing Co: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, M.A.R.; Moore, D.W.; Tuck, B.F.; Wilton, K.M. Self-concept and Anxiety in university students studying Social Science Statistics within a Co-operative Learning Structure. Educ. Psychol. 1998, 18, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Fernández, A.; Ramos-Díaz, E.; Ros, I.; Fernández-Zabala, A.; Revuelta, L. Bienestar subjetivo en la adolescencia: El papel de la resiliencia, El autoconcepto y el apoyo social percibido [Subjective well-being in adolescence: The role of resilience, self-concept and perceived social support]. Suma Psicol. 2016, 23, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Villalobos, J.Á.; Marrero, R.J. Sociodemographic and personal factors determining subjective and psychological well-being in the Mexican population. Suma Psicol. 2017, 24, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuñiga, M. Autoconcepto y Bienestar Psicológico en Estudiantes de una Universidad Privada de Lima Este [Self-Concept and Psychological Well-Being in Students of a Private University of East Lima]. Thesis, Universidad Peruana Unión, Lima, Perú, 13 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Pollans, C.H.; Worden, T.J. Anxiety disorders. In Adult Psychopathology: A Behavioral Perspective; Turner, S.M., Hersen, M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1984; pp. 263–303. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Gorsuch, R.L.; Lushene, R.E. STAI. Cuestionario de Ansiedad Estado/Rasgo [State/Trait Anxiety Questionnaire]; TEA Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger, C.D. (Ed.) Anxiety as an Emotional State. In Anxiety Behavior; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1972; pp. 23–49. [Google Scholar]

- Sandín, B.; Chorot, P. Concepto y categorización de los trastornos de ansiedad [Concept and categorization of anxiety disorders”]. Manual de Psicopatología 2011, 2, 53–80. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.A.; Campbell, L.A.; Lehman, C.L.; Grisham, J.R.; Mancill, R.B. Current and lifetime comorbidity of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders in a large clinical sample. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2001, 110, 585–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuke, C.J.; Fischer, R.; McDowall, J. Anxiety and depression: Why and how to measure their separate effects. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 23, 831–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wata, N.; Higuchi, H.R. Responses of Japanese and American university students to the STAI items that assess the presence or absence of Anxiety. J. Pers. Assess. 2000, 74, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, T.; Diego, M.; Pelaez, M.; Deeds, O.; Delgado, J. Breakup distress in university students. Adolescence 2009, 44, 705–727. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bustamante Oliveros, M.J.; Navarro Saldaña, G. Auto-atribución de comportamientos socialmente responsables de estudiantes de carreras del área de ciencias sociales [Self-attribution of socially responsible behaviors of career students in the area of social sciences]. Rev. Perspect. Notas sobre Interv. y acción Soc. 2018, 18, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Extremera Pacheco, N.; Fernandez Berrocal, P. Inteligencia emocional, calidad de las relaciones interpersonales y empatía en estudiantes universitarios [Emotional intelligence, quality of interpersonal relationships and empathy in university students]. Clínica y Salud 2004, 15, 117–137. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Berrocal, P.; Extremera, N.; Ramos, N. Validity and Reliability of the Spanish Modified Version of the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. Psychol. Rep. 2004, 94, 751–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca-Pedrero, E.; Paino, M.; Sierra-Baigrie, S.; Lemos-Giráldez, S.; Muñiz, J. Propiedades Psicométricas del “Cuestionario de Ansiedad Estado-Rasgo” (STAI) en Universitarios [Psychometric Properties of the “State-Trait Anxiety Questionnaire”]. Behav. Psychol. Psicol. Conduct. 2012, 20, 547–561. [Google Scholar]

- García, F.; Musitu, G. AF5: Autoconcepto Forma 5. [AF5: Form 5 Self-Concept]; TEA Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yamarik, S. Does cooperative learning improve student learning outcomes? J. Econ. Educ. 2007, 38, 259–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgin, I. The effects of guided inquiry instruction incorporating a Cooperative Learning Approach on university students’ achievement of Acid and Aases Concepts and Attitude Toward Guided Inquiry Instruction. Sci. Res. Essay 2009, 4, 1038–1046. [Google Scholar]

- Marriott, P. A longitudinal study of undergraduate accounting students’ learning style preferences at two UK universities. Account. Educ. 2010, 11, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, S.; Mckee, G.; Huntley-Moore, S. Undergraduate nursing students’ learning styles: A longitudinal study. Nurse Educ. Today 2011, 31, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales Rodríguez, F.M.; Pérez-Mármol, J.M.; García Pintor, B.; Morales Rodríguez, A.M. Relación entre metodologías preferidas por estudiantes de grado y otras variables psicoeducativas [The link between methods preferred by students and other psychoeducational factors]. Eur. J. Child Dev. Educ. Psychopathol. 2017, 5, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhiala, P.; Torppa, M.; Vasalampi, K.; Eklund, K.; Poikkeus, A.; Aro, T. Profiles of school motivation and emotional well-being among adolescents: Associations with math and reading performance. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2018, 61, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recabarren, R.E.; Gaillard, C.; Guillod, M.; Martin-Soelch, C. Short-Term effects of a multidimensional stress prevention program on quality of life, well-being and psychological resources. A randomized controlled trial. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souri, H.; Hasanirad, T. Relationship between resilience, optimism and psychological well-being in students of medicine. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 30, 1541–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, C.; Ferradás, M.D.M.; Valle, A.; Núñez, J.C.; Vallejo, G. Profiles of psychological well-being and coping strategies among university students. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Zabala, A.; Goñi, E.; Rodríguez-Fernández, A.; Goñi, A. Un nuevo cuestionario en castellano con escalas de las dimensiones del autoconcepto [A new castellan questionnaire with scales of self-concept dimensions]. Rev. Mex. Psicol. 2015, 32, 149–159. [Google Scholar]

- Extremera, N.; Fernández-Berrocal, P. Emotional intelligence as predictor of mental, social, and physical health in university students. Span. J. Psychol. 2006, 9, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Berrocal, P.; Extremera, N. Special issue on emotional intelligence: An overview. Psicothema 2006, 18, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Burris, J.; Brechting, E.; Salsman, J.; Carlson, C. Factors associated with the psychological well-being and distress of university students. J. Am. Coll. Heal. 2009, 57, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicognani, E.; Pirini, C.; Keyes, C.; Joshanloo, M.; Rostami, R.; Nosratabadi, M. Social participation, sense of community and social well being: A study on American, Italian and Iranian University students. Soc. Indic. Res. 2008, 89, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-López, D.; León-Hernández, S.R.; Barragán-Velásquez, C. Correlación de inteligencia emocional con bienestar psicológico y rendimiento académico en alumnos de licenciatura [Correlation of emotional intelligence with psychological well-being and academic performance in bachelor degree students]. Investig. en Educ. Médica 2015, 4, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazarian, S.S. Family functioning, cultural orientation, and psychological well-being among university students in lebanon. J. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 145, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tümkaya, S. Humor styles and socio-demographic variables as predictors of subjective well-being of Turkish university students. Egit. ve Bilim 2011, 36, 158–170. [Google Scholar]

| Measurement Variables | Min | Max | Mean | SD | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological Well-Being | |||||||

| Self-acceptance | −4.00 | 20.00 | 11.02 | 5.08 | 8.00 | 11.50 | 15.00 |

| Positive relationships | −17.00 | 8.00 | −1.11 | 5.80 | −5.00 | −1.00 | 4.00 |

| Autonomy | −18.00 | 12.00 | −2.13 | 6.02 | −6.00 | −3.00 | 2.00 |

| Environmental mastery | 0.00 | 22.00 | 11.56 | 4.44 | 9.00 | 12.00 | 14.00 |

| Personal growth | −1.00 | 21.00 | 12.53 | 4.81 | 9.00 | 13.00 | 16.00 |

| Purpose-in-life | 2.00 | 29.00 | 19.61 | 4.92 | 16.00 | 20.00 | 23.00 |

| Learning Styles | |||||||

| Active | 5.00 | 85.00 | 12.77 | 6.61 | 11.00 | 12.00 | 14.00 |

| Reflexive | 7.00 | 74.00 | 15.70 | 5.44 | 14.00 | 16.00 | 17.00 |

| Theoretic | 6.00 | 81.00 | 15.33 | 6.11 | 13.00 | 16.00 | 17.00 |

| Pragmatic | 6.00 | 62.00 | 13.76 | 4.64 | 12.00 | 14.00 | 15.00 |

| Learning Methodologies | |||||||

| Traditional | 10.00 | 50.00 | 31.44 | 8.34 | 27.00 | 32.00 | 37.00 |

| Cooperative | 51.00 | 125.00 | 95.54 | 11.99 | 89.00 | 95.00 | 102.00 |

| Social Skills | 21.00 | 78.00 | 65.46 | 8.34 | 60.00 | 65.00 | 73.00 |

| Social Responsibility | 120.00 | 194.00 | 149.76 | 13.77 | 140.75 | 149.00 | 159.00 |

| Emotional Intelligence | |||||||

| Emotional attention | 14.00 | 40.00 | 27.28 | 5.99 | 23.00 | 27.00 | 31.25 |

| Clarity | 14.00 | 38.00 | 25.54 | 4.98 | 22.00 | 25.00 | 29.00 |

| Repair | 16.00 | 45.00 | 31.69 | 4.78 | 28.50 | 31.00 | 35.00 |

| Anxiety | |||||||

| State Anxiety | −30.00 | 21.00 | −9.82 | 10.25 | −17.00 | −11.00 | −2.50 |

| Trait Anxiety | −2.00 | 14.00 | 3.41 | 1.97 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 |

| Empathy | |||||||

| Perspective taking | 0.00 | 103.00 | 13.61 | 8.90 | 10.00 | 13.00 | 17.00 |

| Emotional understanding | −1.00 | 26.00 | 13.30 | 6.06 | 8.00 | 13.00 | 18.00 |

| Empathic stress | −11.00 | 88.00 | 4.50 | 8.55 | 0.75 | 3.50 | 8.00 |

| Empathic happiness | 7.00 | 169.00 | 23.76 | 13.14 | 20.00 | 23.00 | 27.00 |

| Self-concept | |||||||

| Academic/Professional | 23.00 | 594.00 | 422.49 | 109.57 | 372.50 | 445.00 | 493.50 |

| Social | 12.00 | 396.00 | 274.01 | 76.44 | 238.75 | 289.00 | 326.75 |

| Emotional | 25.00 | 532.00 | 264.62 | 121.74 | 169.25 | 263.50 | 339.25 |

| Family | −74.00 | 238.00 | 127.09 | 73.72 | 75.00 | 158.00 | 187.00 |

| Physical | 21.00 | 565.00 | 324.15 | 124.02 | 232.75 | 330.00 | 425.00 |

| Psychological Well-Being Dimensions/Demographic and Psychosocial Variables | Self-Acceptance | Positive Relationships | Autonomy | Environmental Mastery | Personal Growth | Purpose-in-Life |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.000 | −0.052 | 0.041 | −0.034 | −0.015 | −0.078 |

| Sex | −0.029 | 0.093 | −0.086 | −0.006 | 0.103 | 0.039 |

| Learning Style | ||||||

| Active | 0.102 | −0.063 | 0.014 | −0.085 | -0.068 | 0.046 |

| Reflexive | 0.002 | −0.141 | -0.018 | −0.145 | -0.079 | −0.026 |

| Theoretic | 0.026 | −0.126 | -0.005 | −0.157 | -0.091 | −0.016 |

| Pragmatic | 0.028 | −0.166 | 0.030 | −0.150 | -0.125 | −0.003 |

| Learning Methodology | ||||||

| Traditional | −0.125 | −0.026 | −0.092 | −0.064 | −0.131 | −0.119 |

| Cooperative | 0.362** | 0.148 | 0.069 | 0.220* | 0.265** | 0.292** |

| Social Skills | 0.242** | 0.251** | 0.288** | 0.261** | 0.410** | 0.263** |

| Social Responsibility | 0.044 | −0.085 | −0.012 | −0.131 | −0.060 | 0.006 |

| Emotional Intelligence | ||||||

| Emotional attention | 0.218** | 0.279** | −0.066 | 0.175* | 0.230** | 0.279** |

| Clarity | 0.443** | 0.262** | 0.423** | 0.486** | 0.236** | 0.350** |

| Repair | 0.236** | 0.151 | 0.170* | 0.230** | 0.097 | 0.163 |

| Anxiety | ||||||

| State Anxiety | −0.527** | −0.336** | −0.411** | −0.547** | −0.303** | −0.454** |

| Trait Anxiety | −0.029 | −0.188* | −0.091 | −0.120 | −0.148 | −0.095 |

| Empathy | ||||||

| Perspective taking | 0.130 | 0.056 | 0.081 | −0.027 | 0.158 | 0.126 |

| Emotional understanding | 0.298** | 0.382** | 0.331** | 0.376** | 0.448** | 0.326** |

| Empathic stress | 0.046 | 0.037 | −0.102 | −0.104 | −0.011 | 0.041 |

| Empathic happiness | 0.123 | 0.037 | 0.036 | −0.049 | 0.068 | 0.133 |

| Self-concept | ||||||

| Academic/professional | 0.313** | 0.237** | 0.224** | 0.300** | 0.460** | 0.326** |

| Social | 0.382** | 0.477** | 0.276** | 0.400** | 0.423** | 0.329** |

| Emotional | −0.212* | −0.151 | −0.344** | −0.245** | −0.171* | −0.158 |

| Family | 0.451** | 0.291** | 0.145 | 0.368** | 0.376** | 0.386** |

| Physical | 0.526** | 0.260** | 0.245** | 0.374** | 0.206* | 0.399** |

| Self-Acceptance (R2 = 0.586) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | B | 95% CI | β | SE | p-Value | |

| Lower bound | Upper bound | |||||

| Cooperative Learning (Learning Methodologies) | 0.075 | 0.018 | 0.232 | 0.182 | 0.029 | 0.010 |

| Clarity (Emotional Intelligence) | 0.157 | 0.002 | 0.311 | 0.146 | 0.078 | 0.047 |

| State Anxiety | −0.140 | −0.209 | −0.070 | −0.277 | 0.035 | <0.001 |

| Emotional Understanding (Empathy) | 0.144 | 0.020 | 0.268 | 0.163 | 0.063 | 0.023 |

| Physical Self-concept | 0.012 | 0.006 | 0.018 | 0.279 | 0.003 | <0.001 |

| Family Self-concept | 0.019 | 0.009 | 0.029 | 0.265 | 0.005 | <0.001 |

| Positive relationships (R2 = 0.520) | ||||||

| Independent variables | B | 95% CI | β | SE | p-value | |

| Lower bound | Upper bound | |||||

| Active Learning Style | −0.379 | −0.666 | −0.093 | −0.195 | 0.144 | 0.010 |

| Emotional Understanding (Empathy) | 0.263 | 0.107 | 0.419 | 0.261 | 0.079 | 0.001 |

| Empathic Stress (Empathy) | 0.392 | 0.205 | 0.580 | 0.309 | 0.094 | <0.001 |

| Academic/Professional Self-concept | −0.022 | −0.033 | −0.012 | −0.382 | 0.005 | <0.001 |

| Social Self-concept | 0.049 | 0.034 | 0.065 | 0.596 | 0.008 | <0.001 |

| Family Self-concept | 0.018 | 0.006 | 0.030 | 0.227 | 0.006 | 0.003 |

| Autonomy (R2 = 0.313) | ||||||

| Independent variables | B | 95% CI | β | SE | p-value | |

| Lower bound | Upper bound | |||||

| Social Skills | 0.177 | 0.040 | .0315 | 0.219 | 0.069 | 0.012 |

| Emotional Attention (Emotional Intelligence) | 0.246 | −0.430 | −0.061 | −0.247 | 0.093 | 0.010 |

| Clarity (Emotional Intelligence) | 0.484 | 0.252 | 0.715 | 0.391 | 0.117 | <0.001 |

| Emotional Self-concept | −0.011 | −0.020 | −0.002 | −0.217 | 0.004 | 0.014 |

| Environmental mastery (R2 = 0.489) | ||||||

| Independent variables | B | 95% CI | β | SE | p-value | |

| Lower bound | Upper bound | |||||

| Global Emotional Intelligence | 0.114 | 0.054 | 0.174 | 0.291 | 0.030 | <0.001 |

| State Anxiety | −0.160 | −0.221 | −0.100 | −0.397 | 0.030 | <0.001 |

| Emotional Understanding (Empathy) | 0.132 | 0.054 | 0.174 | 0.186 | 0.054 | 0.016 |

| Family Self-concept | 0.013 | 0.005 | 0.022 | 0.238 | 0.004 | 0.002 |

| Personal growth (R2 = 0.354) | ||||||

| Independent variables | B | 95% CI | β | SE | p-value | |

| Lower bound | Upper bound | |||||

| Emotional Attention (Emotional Intelligence) | 0.131 | 0.003 | 0.260 | 0.164 | 0.065 | 0.046 |

| State Anxiety | −0.143 | −0.218 | −0.069 | −0.306 | 0.038 | <0.001 |

| Emotional Understanding (Empathy) | 0.214 | 0.078 | 0.349 | 0.260 | 0.068 | 0.002 |

| Academic/Professional Self-concept | 0.015 | 0.007 | 0.023 | 0.319 | 0.004 | <0.001 |

| Purpose-in-life (R2 = 0.439) | ||||||

| Independent variables | B | 95% CI | β | SE | p-value | |

| Lower bound | Upper bound | |||||

| Global Emotional Intelligence | 0.119 | 0.043 | 0.194 | 0.252 | 0.038 | 0.002 |

| State Anxiety | −0.135 | −0.212 | −0.058 | −0.278 | 0.039 | 0.001 |

| Empathic Happiness (Empathy) | 0.274 | 0.094 | 0.454 | 0.249 | 0.091 | 0.003 |

| Family Self-concept | 0.017 | 0.006 | 0.027 | 0.245 | 0.005 | 0.003 |

| Environmental Mastery (R2 = 0.540) for Pedagogy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | B | 95% CI | β | SE | p-Value | |

| Lower bound | Upper bound | |||||

| State Anxiety | −0.177 | −0.276 | −0.078 | −0.429 | 0.049 | 0.001 |

| Family Self-concept | 0.015 | 0.001 | 0.029 | 0.272 | 0.007 | 0.034 |

| Traditional Learning (Methodology) | 0.189 | 0.072 | 0.307 | 0.423 | 0.058 | 0.002 |

| Emotional Understanding (Empathy) | 0.257 | 0.053 | 0.461 | 0.339 | 0.100 | 0.015 |

| Environmental mastery (R2 = 0.593) for Speech Therapy | ||||||

| Independent variables | B | 95% CI | β | SE | p-value | |

| Lower bound | Upper bound | |||||

| State Anxiety | −0.225 | −0.312 | −0.138 | −0.638 | 0.042 | 0.000 |

| Emotional Attention (Emotional Intelligence) | 0.205 | 0.053 | 0.358 | 0.331 | 0.075 | 0.010 |

| Purpose-in-life (R2 = 0.492) for Pedagogy | ||||||

| Independent variables | B | 95% CI | β | SE | p-value | |

| Lower bound | Upper bound | |||||

| State Anxiety | −0.253 | −0.365 | −0.140 | −0.553 | 0.055 | 0.000 |

| Social Responsibility | 0.153 | 0.070 | 0.237 | 0.479 | 0.041 | 0.001 |

| Theoretic Learning Style | −0.752 | −1.273 | −0.231 | −0.379 | 0.257 | 0.006 |

| Purpose-in-life (R2 = 0.573) for Speech Therapy | ||||||

| Independent variables | B | 95% CI | β | SE | p-value | |

| Lower bound | Upper bound | |||||

| Empathic happiness (Empathy) | 0.744 | 0.143 | 1.075 | 0.689 | 0.162 | 0.000 |

| Empathic Stress (Empathy) | 0.413 | 0.066 | 0.760 | 0.320 | 0.170 | 0.021 |

| Perspective taking (Empathy) | −0.349 | −0.688 | −0.010 | −0.302 | 0.166 | 0.044 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morales-Rodríguez, F.M.; Espigares-López, I.; Brown, T.; Pérez-Mármol, J.M. The Relationship between Psychological Well-Being and Psychosocial Factors in University Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4778. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134778

Morales-Rodríguez FM, Espigares-López I, Brown T, Pérez-Mármol JM. The Relationship between Psychological Well-Being and Psychosocial Factors in University Students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(13):4778. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134778

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorales-Rodríguez, Francisco Manuel, Isabel Espigares-López, Ted Brown, and José Manuel Pérez-Mármol. 2020. "The Relationship between Psychological Well-Being and Psychosocial Factors in University Students" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 13: 4778. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134778

APA StyleMorales-Rodríguez, F. M., Espigares-López, I., Brown, T., & Pérez-Mármol, J. M. (2020). The Relationship between Psychological Well-Being and Psychosocial Factors in University Students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(13), 4778. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134778