Effect of Exercising with Others on Incident Functional Disability and All-Cause Mortality in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Five-Year Follow-Up Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Measurements and Methods

2.2.1. Functional Disability and Mortality

2.2.2. Exercise Habits

2.2.3. Covariates

2.2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- DiPietro, L. Physical activity in aging: Changes in patterns and their relationship to health and function. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. 2001, 56, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pahor, M.; Guralnik, J.M.; Ambrosius, W.T.; Blair, S.; Bonds, D.E.; Church, T.S.; Espeland, M.A.; Fielding, R.A.; Gill, T.M.; Groessl, E.J.; et al. Effect of structured physical activity on prevention of major mobility disability in older adults: The LIFE study randomized clinical trial. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2014, 311, 2387–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasco, J.A.; Williams, L.J.; Jacka, F.N.; Henry, M.J.; Coulson, C.E.; Brennan, S.L.; Leslie, E.; Nicholson, G.C.; Kotowicz, M.A.; Berk, M. Habitual physical activity and the risk for depressive and anxiety disorders among older men and women. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2011, 23, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishimoto, H.; Ohara, T.; Hata, J.; Ninomiya, T.; Yoshida, D.; Mukai, N.; Nagata, M.; Ikeda, F.; Fukuhara, M.; Kumagai, S.; et al. The long-term association between physical activity and risk of dementia in the community: The Hisayama study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 31, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arem, H.; Moore, S.C.; Patel, A.; Hartge, P.; De Gonzalez, A.B.; Visvanathan, K.; Campbell, P.T.; Freedman, M.; Weiderpass, E.; Adami, H.O.; et al. Leisure time physical activity and mortality: A detailed pooled analysis of the dose-response relationship. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015, 175, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, B.; Merom, D.; Blyth, F.M.; Naganathan, V.; Hirani, V.; Le Couteur, D.G.; Seibel, M.J.; Waite, L.M.; Handelsman, D.J.; Cumming, R.G. Total physical activity, exercise intensity, and walking speed as predictors of all-cause and cause-specific mortality over 7 years in older men: The concord health and aging in men project. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2018, 19, 216–222; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piercy, K.L.; Troiano, R.P.; Ballard, R.M.; Carlson, S.A.; Fulton, J.E.; Galuska, D.A.; George, S.M.; Olson, R.D. The physical activity guidelines for Americans. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2018, 320, 2020–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanamori, S.; Takamiya, T.; Inoue, S.; Kai, Y.; Tsuji, T.; Kondo, K. Frequency and pattern of exercise and depression after two years in older Japanese adults: The JAGES longitudinal study. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanamori, S.; Takamiya, T.; Inoue, S.; Kai, Y.; Kawachi, I.; Kondo, K. Exercising alone versus with others and associations with subjective health status in older Japanese: The JAGES cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 39151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, T.; Kondo, K.; Kanamori, S.; Tsuji, T.; Saito, M.; Ochi, A.; Ota, S. Differences in falls between older adult participants in group exercise and those who exercise alone: A cross-sectional study using Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study (JAGES) data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seino, S.; Kitamura, A.; Tomine, Y.; Tanaka, I.; Nishi, M.; Taniguchi, Y.U.; Yokoyama, Y.; Amano, H.; Fujiwara, Y.; Shinkai, S. Exercise arrangement is associated with physical and mental health in older adults. Med. Sci. Sport Exer. 2019, 51, 1146–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanamori, S.; Kai, Y.; Kondo, K.; Hirai, H.; Ichida, Y.; Suzuki, K.; Kawachi, I. Participation in sports organizations and the prevention of functional disability in older Japanese: The AGES cohort study. PLoS One 2012, 7, e51061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsutsui, T.; Muramatsu, N. Care-needs certification in the long-term care insurance system of Japan. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, V.; Saito, Y. How accurate are self-reported height, weight, and BMI among community-dwelling elderly Japanese? Evidence from a national population-based study. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2012, 12, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arai, H.; Satake, S. English translation of the Kihon Checklist. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2015, 15, 518–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Smith, T.B.; Baker, M.; Harris, T.; Stephenson, D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 10, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanamori, S.; Takamiya, T.; Inoue, S. Group exercise for adults and elderly: Determinants of participation in group exercise and its associations with health outcome. J. Phys. Fit. Sports Med. 2015, 4, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, A.; Shankar, A.; Demakakos, P.; Wardle, J. Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 5797–5801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firestone, M.J.; Yi, S.S.; Bartley, K.F.; Eisenhower, D.L. Perceptions and the role of group exercise among New York City adults, 2010–2011: An examination of interpersonal factors and leisure-time physical activity. Prev. Med. 2015, 72, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamakita, M.; Kanamori, S.; Kondo, N.; Kondo, K. Correlates of regular participation in sports groups among Japanese older adults: JAGES cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Baseline Variables | Non-Exercise | Exercising Alone | Exercising with Others | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of participants | 541 | 461 | 518 | ||||

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 73.9 | (6.8) | 73.5 | (6.5) | 72.9 | (5.5) | 0.02 |

| Male sex | 284 | (52.5) | 240 | (52.1) | 217 | (41.9) | <0.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.49 | ||||||

| <18.5 | 28 | (5.2) | 28 | (6.1) | 21 | (4.1) | |

| 18.5–29.9 | 502 | (92.8) | 425 | (92.2) | 491 | (94.8) | |

| ≥30 | 11 | (2.0) | 8 | (1.7) | 6 | (1.2) | |

| Living alone | 60 | (11.1) | 54 | (11.7) | 48 | (9.3) | 0.43 |

| Poor economic condition | 112 | (20.7) | 92 | (20.0) | 84 | (16.2) | 0.14 |

| Stroke | 24 | (4.4) | 19 | (4.1) | 20 | (3.9) | 0.90 |

| Heart diseases | 90 | (16.6) | 61 | (13.2) | 59 | (11.4) | 0.04 |

| Joint pain | 93 | (17.2) | 74 | (16.1) | 103 | (19.9) | 0.27 |

| Fall history | 136 | (25.1) | 97 | (21.0) | 92 | (17.8) | 0.01 |

| Mean (SD) Depressive symptoms (points) | 1.0 | (1.4) | 0.8 | (1.2) | 0.5 | (0.9) | <0.01 |

| Variables | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Exercise | Exercising Alone | Exercising with Others | |||

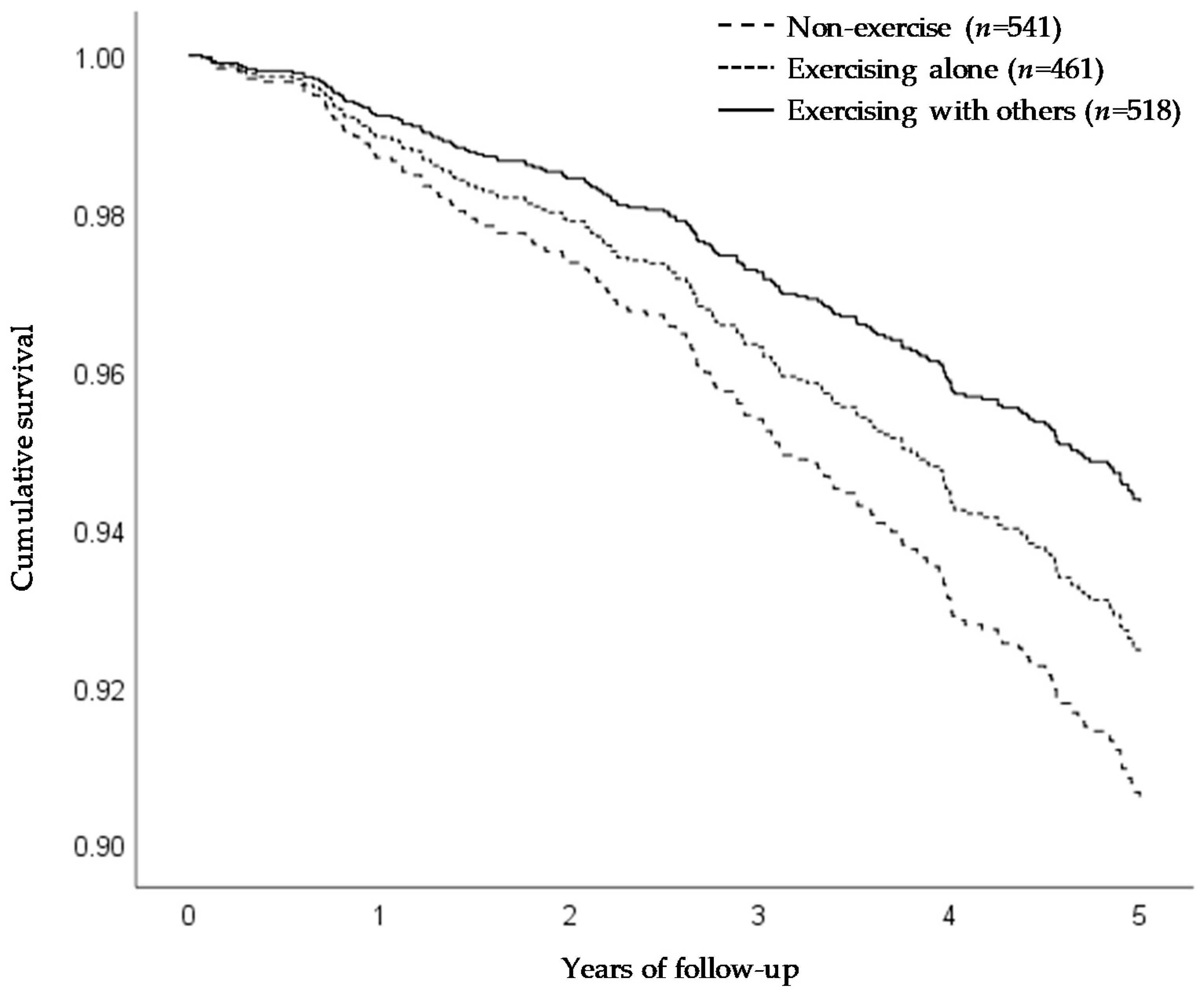

| No. of participants | 541 | 461 | 518 | ||

| No. of person-years | 2479 | 2175 | 2515 | ||

| No. of incidence | 88 | 60 | 37 | ||

| Incidence rates per 1000 person-years | 36 | 28 | 15 | ||

| All subjects | |||||

| Unadjusted | 1.00 | 0.78 | (0.59–1.08) | 0.41 | (0.28–0.61) |

| Model 1 † | 1.00 | 0.81 | (0.59–1.13) | 0.54 | (0.37–0.80) |

| Model 2 ‡ | 1.00 | 0.80 | (0.57–1.11) | 0.59 | (0.40–0.88) |

| Only exercisers | |||||

| Unadjusted | 1.00 | 0.53 | (0.35–0.80) | ||

| Model 1 † | 1.00 | 0.67 | (0.44–1.02) | ||

| Model 2 ‡ | 1.00 | 0.74 | (0.48–1.14) | ||

| Variables | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Exercise | Exercising Alone | Exercising with Others | |||

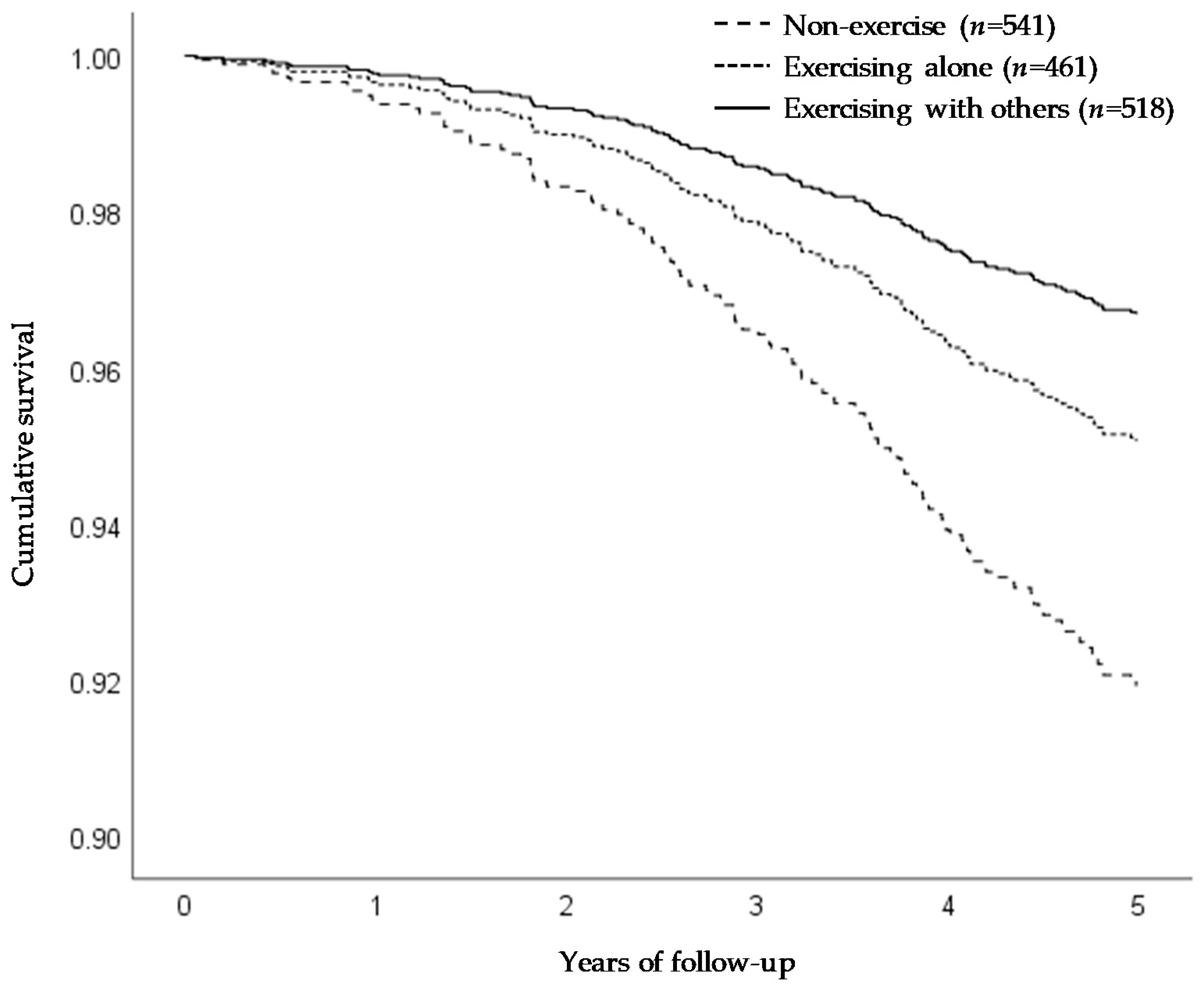

| No. of participants | 541 | 461 | 518 | ||

| No. of person-years | 2546 | 2237 | 2545 | ||

| No. of death | 70 | 37 | 21 | ||

| Incidence rates per 1000 person-years | 28 | 17 | 8 | ||

| All subjects | |||||

| Unadjusted | 1.00 | 0.60 | (0.40–0.89) | 0.31 | (0.18–0.48) |

| Model 1 † | 1.00 | 0.61 | (0.41–0.90) | 0.37 | (0.23–0.61) |

| Model 2 ‡ | 1.00 | 0.60 | (0.40–0.90) | 0.40 | (0.24–0.66) |

| Only exercisers | |||||

| Unadjusted | 1.00 | 0.50 | (0.29–0.85) | ||

| Model 1 † | 1.00 | 0.62 | (0.36–1.06) | ||

| Model 2 ‡ | 1.00 | 0.67 | (0.38–1.17) | ||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fujii, Y.; Fujii, K.; Jindo, T.; Kitano, N.; Seol, J.; Tsunoda, K.; Okura, T. Effect of Exercising with Others on Incident Functional Disability and All-Cause Mortality in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Five-Year Follow-Up Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4329. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124329

Fujii Y, Fujii K, Jindo T, Kitano N, Seol J, Tsunoda K, Okura T. Effect of Exercising with Others on Incident Functional Disability and All-Cause Mortality in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Five-Year Follow-Up Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(12):4329. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124329

Chicago/Turabian StyleFujii, Yuya, Keisuke Fujii, Takashi Jindo, Naruki Kitano, Jaehoon Seol, Kenji Tsunoda, and Tomohiro Okura. 2020. "Effect of Exercising with Others on Incident Functional Disability and All-Cause Mortality in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Five-Year Follow-Up Survey" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 12: 4329. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124329

APA StyleFujii, Y., Fujii, K., Jindo, T., Kitano, N., Seol, J., Tsunoda, K., & Okura, T. (2020). Effect of Exercising with Others on Incident Functional Disability and All-Cause Mortality in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Five-Year Follow-Up Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 4329. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124329