The Impact of COVID-19 on Tourist Satisfaction with B&B in Zhejiang, China: An Importance–Performance Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

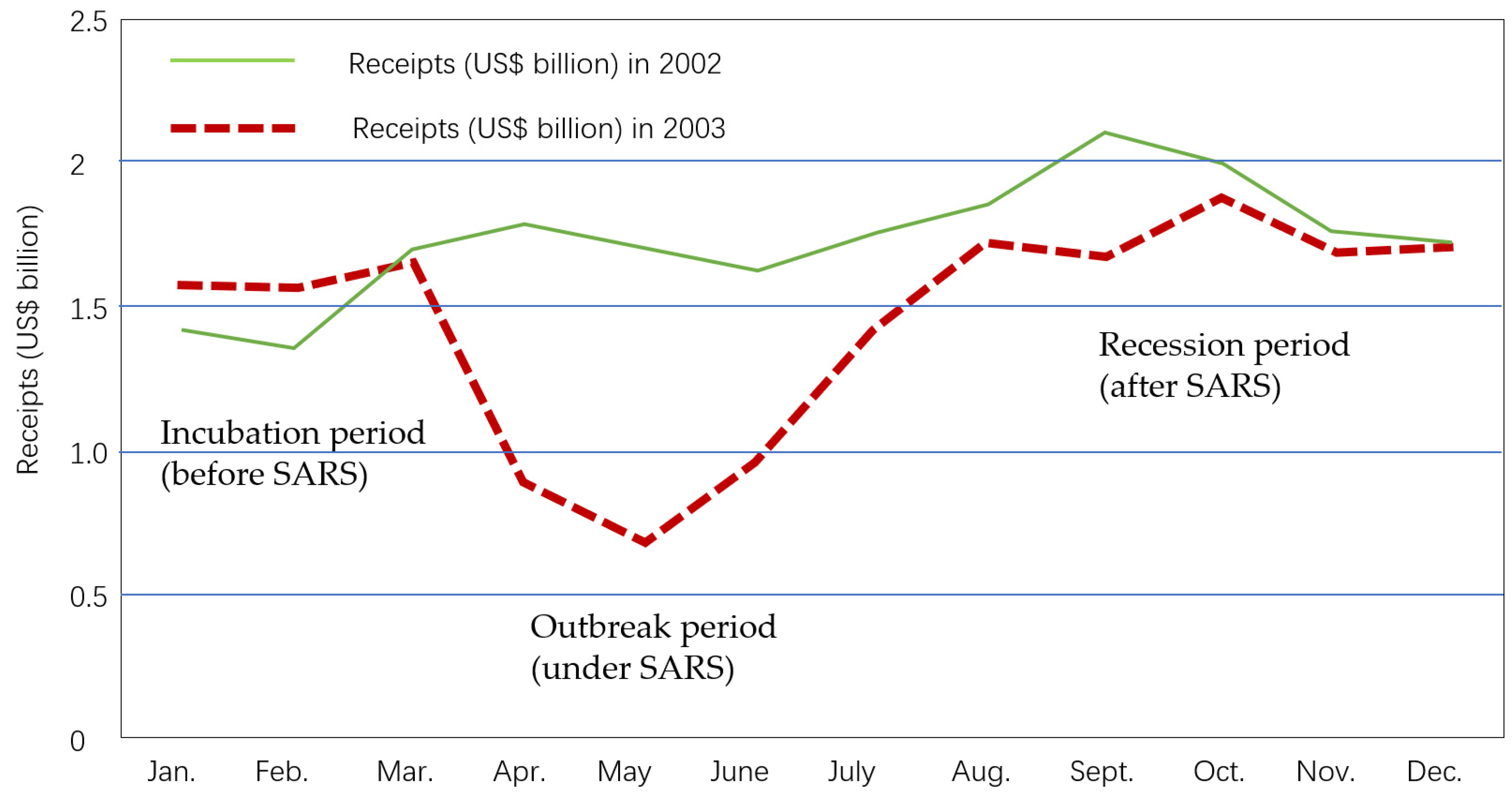

2.1. Crisis (e.g., SARS and COVID-19) Impact on Chinese Tourism and B&B

2.2. Tourism Resumption Post-Crisis (e.g., SARS and COVID-19)

2.3. The Concept of B&B

2.4. B&B in Zhejiang

2.5. Tourist Satisfaction

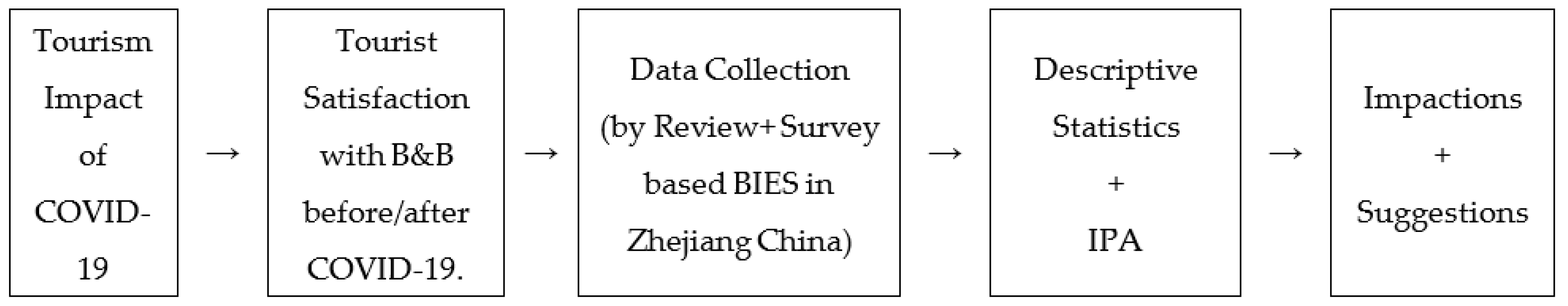

3. Materials and Methods

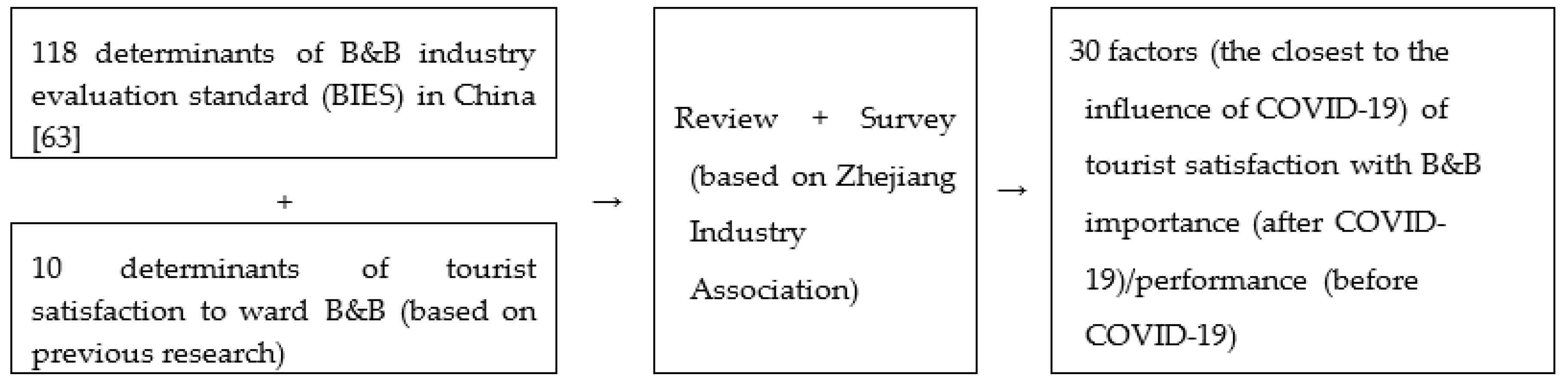

3.1. Data Collection

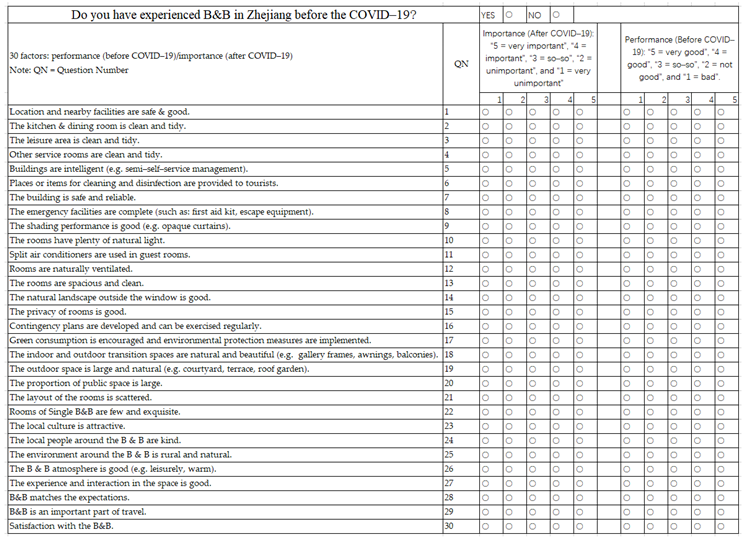

3.1.1. Explanation of Questionnaire

3.1.2. Questionnaire Items

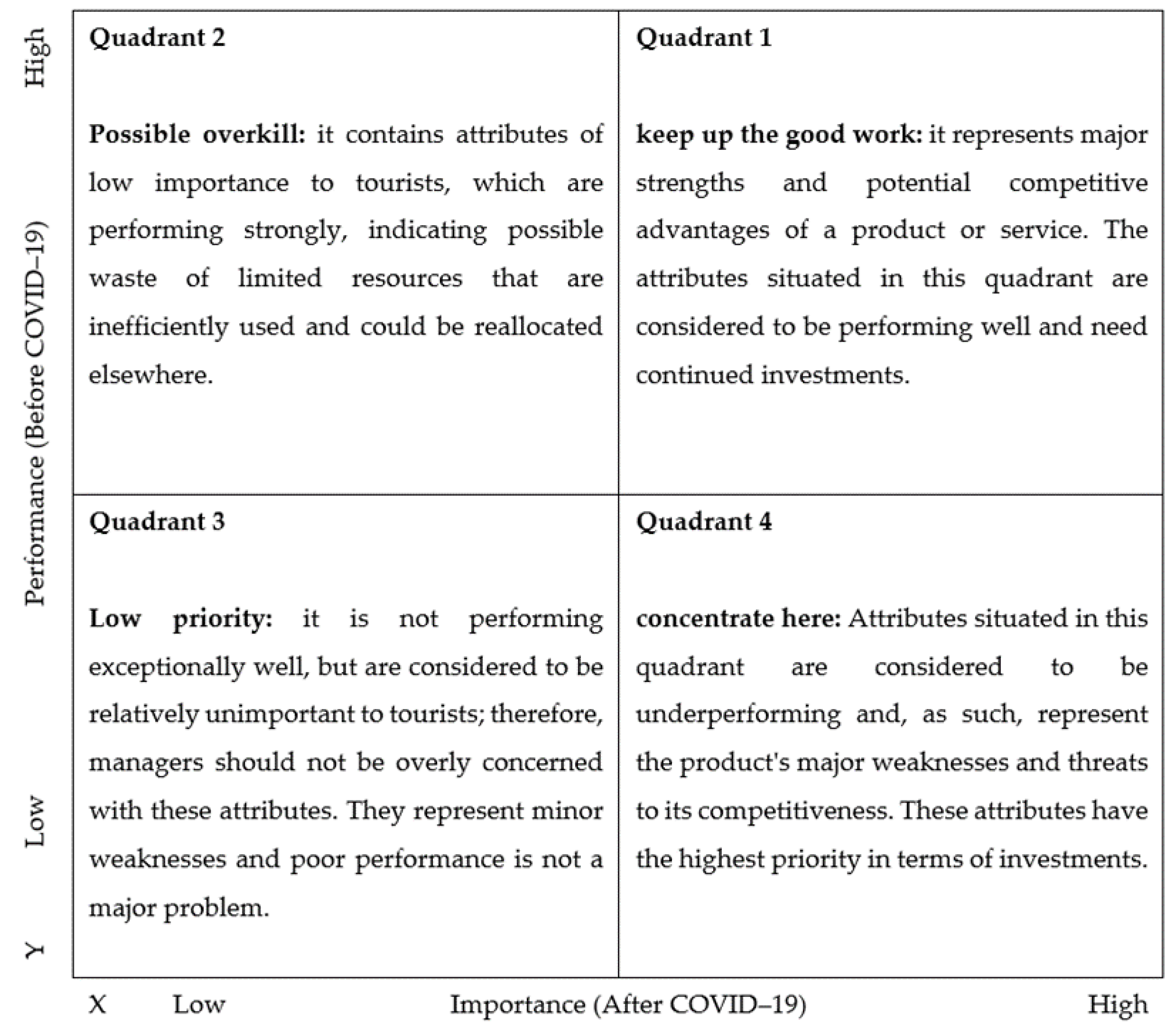

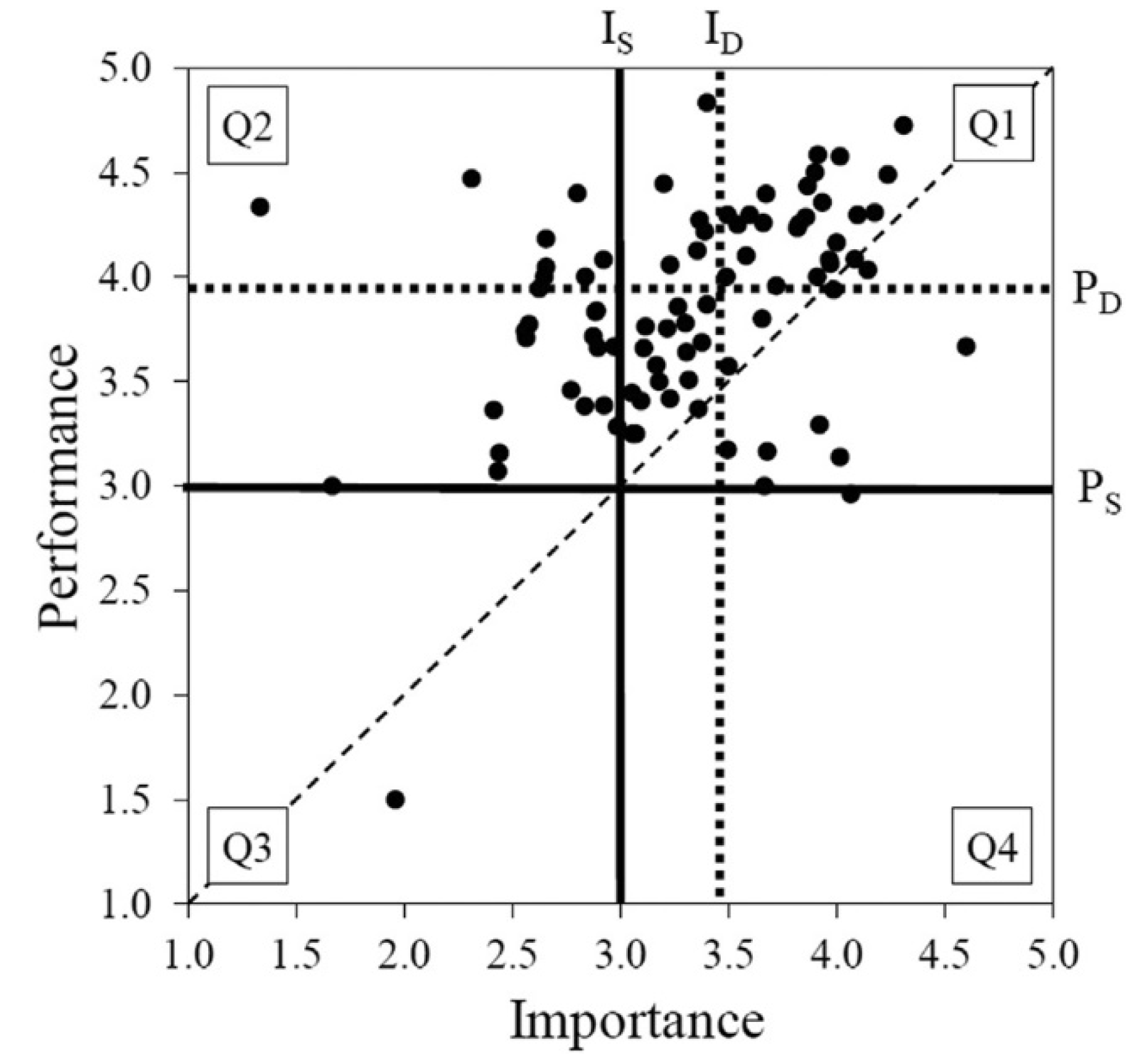

3.2. Importance–Performance Analysis (IPA)

3.2.1. Concept of IPA

3.2.2. Location of the Discriminating Thresholds within the IPA Plot

4. Results

4.1. The Descriptive Statistics

4.1.1. Profile of Survey Respondents

4.1.2. Reliability and Validity Analysis

4.1.3. Importance–Performance Scores

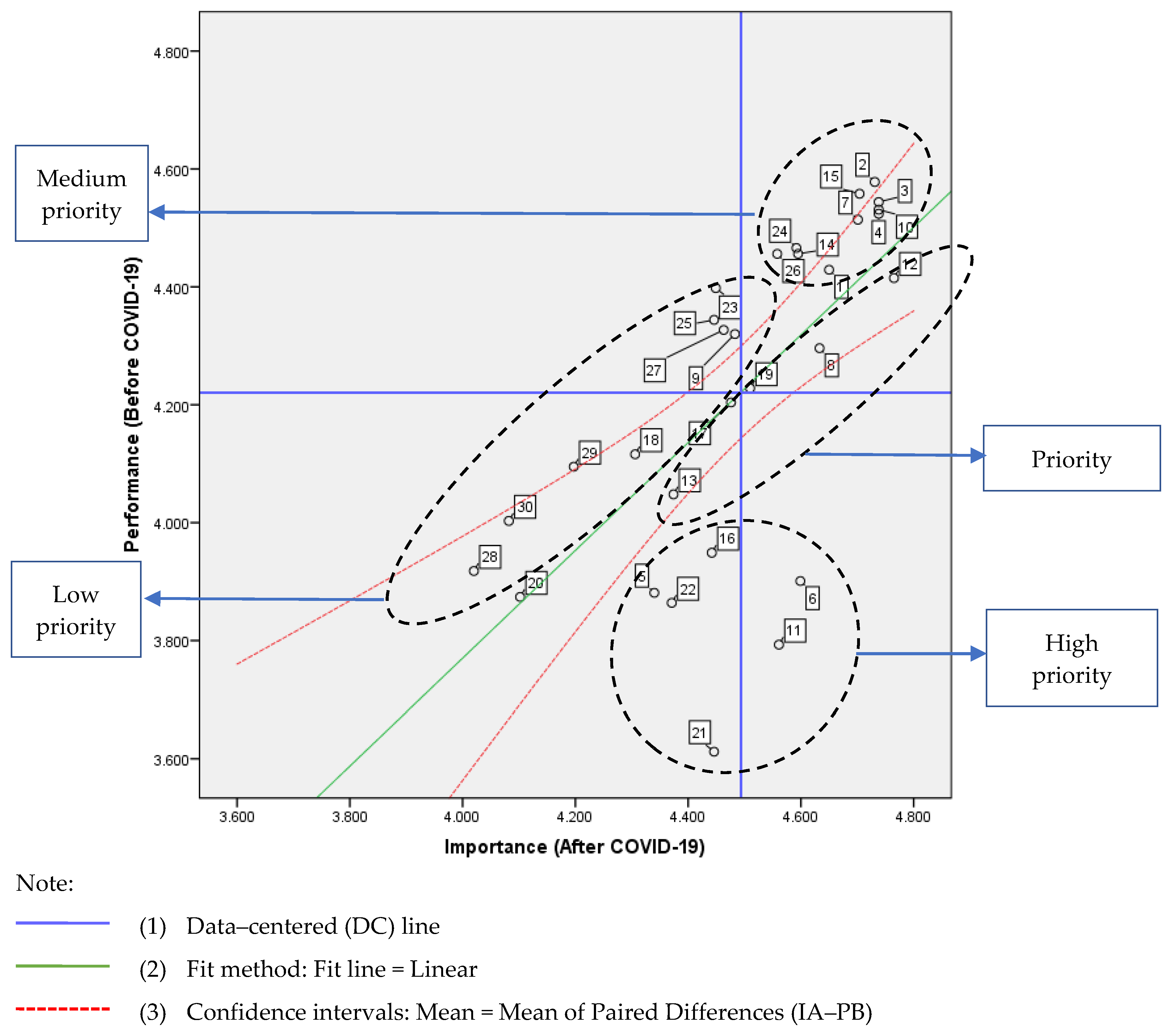

4.2. Importance (after COVID-19)–Performance (before COVID-19) Analysis (IPA)

5. Discussion

5.1. Impacts

Implications

5.2. Suggestions

5.2.1. High Priority Suggestions

5.2.2. Priority Suggestions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Singhal, T. A review of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19). Indian J. Pediatr. 2020, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spagnuolo, G.; De Vito, D.; Rengo, S.; Tatullo, M. COVID-19 Outbreak: An Overview on Dentistry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Stratton, C.W.; Tang, Y.W. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan, China: The mystery and the miracle. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 401–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; McGoogan, J.M. Characteristics of and Important Lessons from the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China: Summary of a Report of 72314 Cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020, 323, 1239–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meltzer, M.I.; Cox, N.J.; Fukuda, K. The economic impact of pandemic influenza in the United States: Priorities for intervention. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 1999, 5, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloomberg Businessweek, Coronavirus Is More Dangerous for the Global Economy Than SARS. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-01-31/the-coronavirus-is-more-dangerous-for-the-economy-than-sars (accessed on 1 May 2020).

- Wang, J.; Wang, Z. Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) Analysis of China’s Prevention and Control Strategy for the COVID-19 Epidemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Work Resumption in China Raises Hope for Virus-Hit European Economies. Available online: https://www.thestar.com.my/news/regional/2020/03/15/work-resumption-in-china-raises-hope-for-virus-hit-european-economies (accessed on 1 May 2020).

- Mouchtouri, V.; Christoforidou, E.P.; Der Heiden, A.; Lemos, C.M.; Fanos, M.; Rexroth, U.; Grote, U.; Belfroid, E.; Swaan, C.M.; Hadjichristodoulou, C.S.; et al. Exit and Entry Screening Practices for Infectious Diseases among Travelers at Points of Entry: Looking for Evidence on Public Health Impact. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yu, J.; Hyun, S.S. Nature based solutions and customer retention strategy: Eliciting customer well-being experiences and self-rated mental health. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 86, 102446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Thilakavathy, K.; Kumar, S.; He, G.; Liu, S. Potential Factors Influencing Repeated SARS Outbreaks in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, B.; Carter, R.; De Lacy, T. Short-term Perturbations and Tourism Effects: The Case of SARS in China. Curr. Issues Tour. 2005, 8, 306–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinhuanet. Zhejiang’s Resumption of Production and Production Started the “Robbery War”. Available online: http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2020-02/20/c_1125598806.htm (accessed on 1 May 2020).

- Chinadaily.com.cn. Research Report on the Development of China B&B Industry in the First Half of 2019. Available online: https://caijing.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201910/24/WS5db16cbca31099ab995e7a64.html (accessed on 1 May 2020).

- Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Xue, J.; Zhao, N.; Zhu, T. The Impact of COVID-19 Epidemic Declaration on Psychological Consequences: A Study on Active Weibo Users. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, Z.F. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health and Quality of Life among Local Residents in Liaoning Province, China: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, D.L.; Guan, J.J. Bed and Breakfast Lodging Development in Mainland China: Who is the Potential Customer? Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 16, 517–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Xiao, H.; Lingqiang, Z. Small accommodation business growth in rural areas: Effects on guest experience and financial performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Sial, M.S.; Usman, S.M.; Hwang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Shafiq, A. What Factors Affect Patient Satisfaction in Public Sector Hospitals: Evidence from an Emerging Economy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwel, S.; Lingqiang, Z.; Asif, M.; Hwang, J.; Hussain, A.; Jameel, A. The Influence of Destination Image on Tourist Loyalty and Intention to Visit: Testing a Multiple Mediation Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martilla, J.A.; James, J.C. Importance-Performance Analysis. J. Mark. 1977, 41, 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sever, I. Importance-performance analysis: A valid management tool? Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Ritchie, B.W.; Walters, G. Towards a research agenda for post-disaster and post-crisis recovery strategies for tourist destinations: A narrative review. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 19, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giupponi, G.; Innamorati, M.; Rogante, E.; Sarubbi, S.; Erbuto, D.; Maniscalco, I.; Sanna, L.; Conca, A.; Lester, D.; Pompili, M. The Characteristics of Mood Polarity, Temperament, and Suicide Risk in Adult ADHD. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafini, G.; Parisi, V.; Aguglia, A.; Amerio, A.; Sampogna, G.; Fiorillo, A.; Pompili, M.; Amore, M. A Specific Inflammatory Profile Underlying Suicide Risk? Systematic Review of the Main Literature Findings. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napoli, A.; Lamis, D.A.; Berardelli, I.; Canzonetta, V.; Sarubbi, S.; Rogante, E.; Napoli, P.-L.; Serafini, G.; Erbuto, D.; Tambelli, R.; et al. Anxiety, Prenatal Attachment, and Depressive Symptoms in Women with Diabetes in Pregnancy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael Hall, C. Crisis events in tourism: Subjects of crisis in tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2010, 13, 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilder-Smith, A. Tourism and SARS; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; ISBN 0080446663. [Google Scholar]

- Fakeye, P.C.; Crompton, J.L. Image Differences between Prospective, First-Time, and Repeat Visitors to the Lower Rio Grande Valley. J. Travel Res. 1991, 30, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunovic, I. Satisfaction of tourists in Serbia, destination image, loyalty and DMO service quality. Eur. J. Tour. Hosp. Recreat. 2014, 5, 163–181. [Google Scholar]

- Paunović, I. Proposal for Serbian Tourism Destinations Marketing Campaign/Predlog Za Marketinšku Kampanju Srpskih Turističkih Destinacija. Eur. J. Appl. Econ. 2013, 10, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Han, H.; Lee, S.; Hyun, S.S. Role of Internal and External Museum Environment in Increasing Visitors’ Cognitive/Affective/Healthy Experiences and Loyalty. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunović, I.; Jovanovic, V. Sustainable mountain tourism in word and deed: A comparative analysis in the macro regions of the Alps and the Dinarides. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2019, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunovic, I.; Jovanovic, V. Implementation of Sustainable Tourism in the German Alps: A Case Study. Sustainability 2017, 9, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-K.; Lee, Y.-K.; Lee, B. Korea’s destination image formed by the 2002 World Cup. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 839–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, W.C. Image Formation Process. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1994, 2, 191–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ritchie, B.W. A theoretical model for strategic crisis planning: Factors influencing crisis planning in the hotel industry. Int. J. Tour. Policy 2010, 3, 297–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, B. Tourism disaster planning and management: From response and recovery to reduction and readiness. Curr. Issues Tour. 2008, 11, 315–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Wang, J.; Xu, L.; Gao, W. Observations of Chinese City Architecture Biennale Driven by Economy. J. Asian Inst. Low Carbon Des. 2020, 01, 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, G.; Xu, L.; Gao, W.; Zhang, Y. A Review of the Studies on the China Architecture Exhibition. J. Asian Inst. Low Carbon Des. 2020, 01, 97–102. [Google Scholar]

- Nuntsu, N.; Tassiopoulos, D.; Haydam, N. The bed and breakfast market of Buffalo City (BC), South Africa: Present status, constraints and success factors. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, P.A. The commercial home enterprise and host: A United Kingdom perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2005, 24, 533–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Mi, C.; Chen, Y.; Huang, L. Understanding the determinants of consumer satisfaction with B&B hotels: An interpretive structural modeling approach. Int. J. Web Serv. Res. 2019, 16, 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.-C.; Lin, S.-P.; Kuo, C.-M. Rural tourism: Marketing strategies for the bed and breakfast industry in Taiwan. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 32, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.-N. How can managerial efficiency be improved? Evidence from the bed and breakfast industry. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 27, 111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, Y.-C.J.; Lin, Y.-H.P. Bed and Breakfast operators’ work and personal life balance: A cross-cultural comparison. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R. Research on the B&B (Bed and Breakfast) Market Network Attention in China Based on Baidu Index. In Proceedings of the 2019 2nd International Workshop on Advances in Social Sciences (IWASS 2019), London, UK, 28–30 November 2019; Volume 2, pp. 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kozak, M.; Bigne, E.; Andreu, L. Limitations of Cross-Cultural Customer Satisfaction Research and Recommending Alternative Methods. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2004, 4, 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, A.; Trobia, F.; Gualtieri, F.; Lamis, D.A.; Cardamone, G.; Giallonardo, V.; Fiorillo, A.; Girardi, P.; Pompili, M. Suicide Risk among Immigrants and Ethnic Minorities: A Literature Overview. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hau, T.C.; Omar, K. The Impact of Service Quality on Tourist Satisfaction: The Case Study of Rantau Abang Beach as a Turtle Sanctuary Destination. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardelli, I.; Sarubbi, S.; Lamis, D.A.; Rogante, E.; Canzonetta, V.; Negro, A.; Guglielmetti, M.; Sparagna, A.; De Angelis, V.; Erbuto, D.; et al. Job Satisfaction Mediates the Association between Perceived Disability and Work Productivity in Migraine Headache Patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M.; Rimmington, M. Tourist Satisfaction with Mallorca, Spain, as an Off-Season Holiday Destination. J. Travel Res. 2000, 38, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeiwaah, E.; Adongo, R.; Dimache, A.O.; Wondirad, A.N. Make a customer, not a sale: Tourist satisfaction in Hong Kong. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F.; Chen, F.-S. Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Xu, L.; Gao, W.; Hong, Y.; Ying, X.; Wang, Y.; Qian, F. The Positive Impacts of Exhibition-Driven Tourism on Sustainable Tourism, Economics, and Population: The Case of the Echigo–Tsumari Art Triennale in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, M.; Kim, I.; Hwang, J. Can Local People Help Enhance Tourists’ Destination Loyalty? A Relational Perspective. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 702–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalwar, S.; Sahito, N.; Memon, I.; Hwang, J.; Mangi, M.Y.; Lashari, Z.A. National Planning Strategies for Agro-based Industrial Development in Secondary Cities of Sindh Province, Pakistan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Kim, H. Consequences of a green image of drone food delivery services: The moderating role of gender and age. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2019, 28, 872–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, S.S.; Perdue, R.R. Understanding the dimensions of customer relationships in the hotel and restaurant industries. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 64, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, S.S.; Kim, W.; Lee, M.J. The impact of advertising on patrons’ emotional responses, perceived value, and behavioral intentions in the chain restaurant industry: The moderating role of advertising-induced arousal. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, S.S.; Kang, J. A better investment in luxury restaurants: Environmental or non-environmental cues? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 39, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, S.S. Creating a model of customer equity for chain restaurant brand formation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, T.Y.; Chu, R. Determinants of hotel guests’ satisfaction and repeat patronage in the Hong Kong hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2001, 20, 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-H.; Hyun, S.S.; Park, H.; Kim, K. The Antecedents and Consequences of Psychological Safety in Airline Firms: Focusing on High-Quality Interpersonal Relationships. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Yeh, M.; Sung, M. A customer satisfaction index model for international tourist hotels: Integrating consumption emotions into the American Customer Satisfaction Index. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 35, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.G.; Ma, X.; Kim, D.J. Determinants of Chinese hotel customers’ e-satisfaction and purchase intentions. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 890–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-L. The Impact of Bed and Breakfast Atmosphere, Customer Experience, and Customer Value on Customer Voluntary Performance: A Survey in Taiwan. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 20, 541–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Han, H.; Choo, S.-W. A strategy for the development of the private country club: Focusing on brand prestige. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 1927–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, J. (Jay) Understanding customer-customer rapport in a senior group package context. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 2187–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Cho, S.-B.; Kim, W. Philanthropic corporate social responsibility, consumer attitudes, brand preference, and customer citizenship behavior: Older adult employment as a moderator. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2019, 47, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.-L.; Liu, C.-C.; Tseng, S.-R. An evaluation of Taiwanese B&B service quality using the IPA model. J. Bus. Res. Turk 2012, 4, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Dressler, M.; Paunovic, I. An exploration of digital innovation activity of German wineries in the regional tourism context: Differentiation and complementarity. In Proceedings of the 1st International Research Workshop on Wine Tourism: Challenges and Futures Perspectives, Strasbourg, France, 27–28 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dressler, M. Strategic profiling and the value of wine & tourism initiatives. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2017, 29, 484–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åke Nilsson, P. Staying on farms: An ideological background. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Fiore, A.M.; Jeoung, M. Measuring Experience Economy Concepts: Tourism Applications. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.T.; Lee, H. Exploring the dimensions of bed and breakfast (B&B) visitors’ experiences. Int. J. Tour. Sci. 2019, 19, 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xiao, L.; Mi, C. Opinion mining from online reviews: Consumer satisfaction analysis with B&B hotels. In Proceedings of the Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems (PACIS), Langkawi, Malaysia, 19 July 2017; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, S.O.; Hwang, J. Are the days of tourist information centers gone? Effects of the ubiquitous information environment. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. The antecedents and consequences of visitors’ participation in a private country club community: The moderating role of extraversion. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 7, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. SERQUAL: A Multiple-Item scale for Measuring Consumer Perceptions of Service Quality. J. Retail. 1988, 64, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Chua, B.-L.; Hyun, S.S. Eliciting customers’ waste reduction and water saving behaviors at a hotel. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, 102386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. What influences water conservation and towel reuse practices of hotel guests? Tour. Manag. 2018, 64, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimes, S.E.; Fitzsimmons, J.A. Selecting Profitable Hotel Sites at La Quinta Motor Inns. Interfaces 1990, 20, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Havlena, W.J.; Holbrook, M.B. The Varieties of Consumption Experience: Comparing Two Typologies of Emotion in Consumer Behavior. J. Consum. Res. 1986, 13, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, S.S.; Han, H. Luxury cruise travelers: Other customer perceptions. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syaqirah, Z.N.; Faizurrahman, Z.P. Managing Customer Retention of Hotel Industry in Malaysia. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 130, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer Perceptions of Price, Quality, and Value: A Means-End Model and Synthesis of Evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective on the Consumer: A Behavioral Perspective on the Consumer, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 1317460227. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Park, H.; Ahn, Y. The Influence of Tourists’ Experience of Quality of Street Foods on Destination’s Image, Life Satisfaction, and Word of Mouth: The Moderating Impact of Food Neophobia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 17, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Park, Y. An Integrated Approach to Determining Rural Tourist Satisfaction Factors Using the IPA and Conjoint Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C.; Zheng, Q.; Ng, P. A Study on the Coordinative Green Development of Tourist Experience and Commercialization of Tourism at Cultural Heritage Sites. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, J. (Jay) Relationships among Senior Tourists’ Perceptions of Tour Guides’ Professional Competencies, Rapport, Satisfaction with the Guide Service, Tour Satisfaction, and Word of Mouth. J. Travel Res. 2018, 58, 1331–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, J.W.; Liu, Y.; Fan, Z.P.; Zhang, J. Wisdom of crowds: Conducting importance-performance analysis (IPA) through online reviews. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 460–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hwang, J. Growing competition in the healthcare tourism market and customer retention in medical clinics: New and experienced travellers. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 21, 680–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, C.; Kim, J.; Chi, S. Quantifying the dynamic effects of smart city development enablers using structural equation modeling. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 53, 101916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, I.; Ștefan, S.C. Modeling the Pathways of Knowledge Management Towards Social and Economic Outcomes of Health Organizations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, J. A strategy for enhancing senior tourists’ well-being perception: Focusing on the experience economy. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 36, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L.; Cvelbar, L.K.; Edwards, D.; Mihalič, T. Fashioning a destination tourism future: The case of Slovenia. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abalo, J.; Varela, J.; Manzano-Arrondo, V. Importance values for Importance–Performance Analysis: A formula for spreading out values derived from preference rankings. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzler, K.; Bailom, F.; Hinterhuber, H.H.; Renzl, B.; Pichler, J. The asymmetric relationship between attribute-level performance and overall customer satisfaction: A reconsideration of the importance–performance analysis. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2004, 33, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H. Revisiting importance–performance analysis. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, D.R. A Comparison of Approaches to Importance-Performance Analysis. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2003, 45, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzopardi, E.; Nash, R. A critical evaluation of importance–performance analysis. Tour. Manag. 2013, 35, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, J.; Dearden, P.; Rollins, R. But are tourists satisfied? Importance-performance analysis of the whale shark tourism industry on Isla Holbox, Mexico. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 692–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberty, S.; Mihalik, B.J. The Use of Importance-Performance Analysis as an Evaluative Technique in Adult Education. Eval. Rev. 1989, 13, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadagnolo, F. The importance-performance analysis: An evaluation and marketing tool. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 1985, 3, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hollenhorst, S.J.; Olson, D.; Fortney, R. Use of importance-performance analysis to evaluate state park cabins: The case of the West Virginia state park system. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 1992, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, I.K.W.; Hitchcock, M. Importance–performance analysis in tourism: A framework for researchers. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 242–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arana, J.E.; León, C.J. Correcting for Scale Perception Bias in Tourist Satisfaction Surveys. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 772–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rial, A.; Rial, J.; Varela, J.; Real, E. An application of importance-performance analysis (IPA) to the management of sport centres. Manag. Leis. 2008, 13, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzler, K.; Sauerwein, E.; Heischmidt, K. Importance-performance analysis revisited: The role of the factor structure of customer satisfaction. Serv. Ind. J. 2003, 23, 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Qing, M.; Hwang, J.; Shi, H. Ethical leadership, affective commitment, work engagement, and creativity: Testing a multiple mediation approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Jameel, A.; Hussain, A.; Hwang, J.; Sahito, N. Linking Transformational Leadership with Nurse-Assessed Adverse Patient Outcomes and the Quality of Care: Assessing the Role of Job Satisfaction and Structural Empowerment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Sahito, N.; Nguyen, T.V.T.; Hwang, J.; Asif, M. Exploring the Features of Sustainable Urban Form and the Factors that Provoke Shoppers towards Shopping Malls. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Jameel, A.; Sahito, N.; Hwang, J.; Hussain, A.; Manzoor, F. Can Leadership Enhance Patient Satisfaction? Assessing the Role of Administrative and Medical Quality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hwang, J.; Lee, M.J.; Kim, J. Word-of-mouth, buying, and sacrifice intentions for eco-cruises: Exploring the function of norm activation and value-attitude-behavior. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Han, H. Understanding Other Customer Perceptions in the Private Country Club Industry. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 20, 875–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hwang, J.; Lee, S. Cognitive, affective, normative, and moral triggers of sustainable intentions among convention-goers. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 51, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Determinants of Tourist Satisfaction to Ward B&B (Based on Previous Research) | 30 Factors: Importance (after COVID-19)/ Performance (before COVID-19) | QN |

|---|---|---|

| B&B Location [18,43,77] | Location and nearby facilities are safe and good. | 1 |

| Facility Quality [18,43,77] | The kitchen and dining room are clean and tidy. | 2 |

| The leisure area is clean and tidy. | 3 | |

| Other service rooms are clean and tidy. | 4 | |

| Buildings are intelligent (e.g., semi–self–service management). | 5 | |

| Places or items for cleaning and disinfection are provided to tourists. | 6 | |

| The building is safe and reliable. | 7 | |

| Room Quality [18,43,77] | The emergency facilities are complete (such as: first aid kit, escape equipment). | 8 |

| The shading performance is good (e.g., opaque curtains). | 9 | |

| The rooms have plenty of natural light. | 10 | |

| Split air conditioners are used in guest rooms. | 11 | |

| Rooms are naturally ventilated. | 12 | |

| The rooms are spacious and clean. | 13 | |

| The natural landscape outside the window is good. | 14 | |

| The privacy of rooms is good. | 15 | |

| Service Quality [80,81] | Contingency plans are developed and can be exercised regularly. | 16 |

| Green consumption is encouraged and environmental protection measures are implemented. | 17 | |

| Specialties [77,82] | The indoor and outdoor transition spaces are natural and beautiful (e.g., gallery frames, awnings, balconies). | 18 |

| The outdoor space is large and natural (e.g., courtyard, terrace, roof garden). | 19 | |

| The proportion of public space is large. | 20 | |

| The layout of the rooms is scattered. | 21 | |

| Rooms of Single B&B are few and exquisite. | 22 | |

| The local culture is attractive. | 23 | |

| Surrounding Environment [83] | The local people around the B&B are kind. | 24 |

| The environment around the B&B is rural and natural. | 25 | |

| Consumption Emotion [84,85] | The B & B atmosphere is good (e.g., leisurely, warm). | 26 |

| The experience and interaction in the space is good. | 27 | |

| Expectation Fulfillment [86] | B&B matches the expectations. | 28 |

| Perceived Value [87] | B&B is an important part of travel. | 29 |

| Satisfaction [88,89] | Satisfaction with the B&B. | 30 |

| Variable | n | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 260 | 44.22% |

| Female | 328 | 55.78% |

| Age | ||

| 25–35 | 270 | 45.92% |

| 36–45 | 122 | 20.75% |

| 46–55 | 114 | 19.39% |

| 56–65 | 36 | 6.12% |

| Other | 46 | 7.82% |

| Educational Level | ||

| Associate’s degree | 68 | 11.56% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 300 | 51.02% |

| Graduate degree | 190 | 32.31% |

| Other | 30 | 5.10% |

| Monthly income (US dollar) | ||

| <500 | 36 | 6.12% |

| 501–800 | 114 | 19.39% |

| 801–1200 | 270 | 45.92% |

| 1201–2000 | 122 | 20.75% |

| >2001 | 46 | 7.82% |

| Occupation | ||

| Civil servant | 20 | 3.40% |

| Company employee | 202 | 34.35% |

| Student | 84 | 14.29% |

| Professional | 96 | 16.33% |

| Self–employed | 78 | 13.27% |

| Other | 108 | 18.37% |

| Number | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Valid | 588 | 100 |

| Excludeda | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 588 | 100 | |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | Number of Items |

|---|---|

| 0.978 | 30 IA + 30 PB |

| Paired Differences (IA–PB) | IA | PB | Pearson Correlation | Sig. (2–Tailed) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QN | Mean | Rank | Std. Deviation | Mean | Rank | Mean | Rank | ||

| 21 | 0.833 | 1 | 1.342 | 4.020 | 30 | 3.918 | 24 | 0.299 | 0.000 |

| 11 | 0.769 | 2 | 1.271 | 4.510 | 15 | 4.228 | 17 | 0.370 | 0.000 |

| 6 | 0.697 | 3 | 1.114 | 4.595 | 11 | 4.456 | 8 | 0.426 | 0.000 |

| 22 | 0.507 | 4 | 1.196 | 4.197 | 27 | 4.095 | 20 | 0.446 | 0.000 |

| 16 | 0.493 | 5 | 1.037 | 4.449 | 19 | 4.398 | 12 | 0.547 | 0.000 |

| 5 | 0.459 | 6 | 1.043 | 4.374 | 23 | 4.048 | 21 | 0.555 | 0.000 |

| 12 | 0.350 | 7 | 0.827 | 4.731 | 5 | 4.578 | 1 | 0.539 | 0.000 |

| 8 | 0.337 | 8 | 0.922 | 4.442 | 22 | 3.949 | 23 | 0.541 | 0.000 |

| 13 | 0.327 | 9 | 0.871 | 4.102 | 28 | 3.874 | 27 | 0.655 | 0.000 |

| 19 | 0.282 | 10 | 0.845 | 4.558 | 14 | 4.456 | 9 | 0.596 | 0.000 |

| 17 | 0.272 | 11 | 0.805 | 4.592 | 12 | 4.466 | 7 | 0.677 | 0.000 |

| 20 | 0.228 | 12 | 1.057 | 4.463 | 18 | 4.327 | 14 | 0.537 | 0.000 |

| 1 | 0.221 | 13 | 0.740 | 4.650 | 8 | 4.429 | 10 | 0.649 | 0.000 |

| 4 | 0.214 | 14 | 0.728 | 4.765 | 1 | 4.415 | 11 | 0.605 | 0.000 |

| 10 | 0.207 | 15 | 0.696 | 4.306 | 26 | 4.116 | 19 | 0.635 | 0.000 |

| 3 | 0.194 | 16 | 0.665 | 4.561 | 13 | 3.793 | 29 | 0.642 | 0.000 |

| 18 | 0.190 | 17 | 0.741 | 4.446 | 20 | 4.344 | 13 | 0.727 | 0.000 |

| 7 | 0.187 | 18 | 0.682 | 4.704 | 6 | 4.558 | 2 | 0.669 | 0.000 |

| 9 | 0.163 | 19 | 0.686 | 4.476 | 17 | 4.204 | 18 | 0.736 | 0.000 |

| 2 | 0.153 | 20 | 0.634 | 4.738 | 3 | 4.531 | 4 | 0.665 | 0.000 |

| 15 | 0.146 | 21 | 0.662 | 4.371 | 24 | 3.864 | 28 | 0.661 | 0.000 |

| 14 | 0.139 | 22 | 0.684 | 4.446 | 21 | 3.612 | 30 | 0.688 | 0.000 |

| 27 | 0.136 | 23 | 0.780 | 4.599 | 10 | 3.901 | 25 | 0.631 | 0.000 |

| 24 | 0.126 | 24 | 0.762 | 4.082 | 29 | 4.003 | 22 | 0.623 | 0.000 |

| 28 | 0.102 | 25 | 0.891 | 4.701 | 7 | 4.514 | 6 | 0.701 | 0.006 |

| 29 | 0.102 | 26 | 0.722 | 4.633 | 9 | 4.296 | 16 | 0.755 | 0.001 |

| 25 | 0.102 | 27 | 0.717 | 4.738 | 4 | 4.524 | 5 | 0.728 | 0.001 |

| 26 | 0.102 | 28 | 0.678 | 4.340 | 25 | 3.881 | 26 | 0.693 | 0.000 |

| 30 | 0.078 | 29 | 0.773 | 4.483 | 16 | 4.320 | 15 | 0.709 | 0.014 |

| 23 | 0.051 | 30 | 0.711 | 4.738 | 2 | 4.544 | 3 | 0.726 | 0.042 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hong, Y.; Cai, G.; Mo, Z.; Gao, W.; Xu, L.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, J. The Impact of COVID-19 on Tourist Satisfaction with B&B in Zhejiang, China: An Importance–Performance Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3747. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103747

Hong Y, Cai G, Mo Z, Gao W, Xu L, Jiang Y, Jiang J. The Impact of COVID-19 on Tourist Satisfaction with B&B in Zhejiang, China: An Importance–Performance Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(10):3747. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103747

Chicago/Turabian StyleHong, Yan, Gangwei Cai, Zhoujin Mo, Weijun Gao, Lei Xu, Yuanxing Jiang, and Jinming Jiang. 2020. "The Impact of COVID-19 on Tourist Satisfaction with B&B in Zhejiang, China: An Importance–Performance Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 10: 3747. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103747

APA StyleHong, Y., Cai, G., Mo, Z., Gao, W., Xu, L., Jiang, Y., & Jiang, J. (2020). The Impact of COVID-19 on Tourist Satisfaction with B&B in Zhejiang, China: An Importance–Performance Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3747. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103747