1. Introduction

The stigma ascribed to individuals with mental illnesses is not solely a concern among the general public. The incidence of mental health stigmatization in the healthcare system and among healthcare providers is surprising. Mental illness stigma can transpire at intrapersonal, interpersonal, and structural levels [

1]. Individuals with mental illnesses frequently report feeling “devalued, dismissed, and dehumanized” [

1] (p. 111) when coming into contact with health professionals.

Stigma is a multi-faceted construct and contributes to all aspects of a person’s life. According to the Mental Health Commission of Canada, “stigma is typically a social process, experienced or anticipated, characterized by exclusion, rejection, blame or devaluation that results from experience or reasonable anticipation of an adverse social judgment about a person or group” [

2]. Such definition stresses that stigma is a negative social product and involves knowledge, emotional, and behavioral aspects. Stigma can be viewed from different perspectives in the literature of sociology, psychology, and medicine. Goffman (1963) first proposed three different types of stigma: (1) abominations of the body, related to physical deformities; (2) blemishes of individual character, such as weak will, mental disorder, or unemployment; and (3) tribal stigma of race, nation, or religion [

3] (p. 4). The former two are also referred to as health-related stigma. Health-related stigma has both disease-specific and culture-specific characteristics [

4]. Manifestations of negative perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors vary as they apply to different health problems in different environments. Among many health conditions, mental illness need to be addressed as a matter of priority because the general public seems to disapprove of persons with psychiatric disabilities more than persons with physical disabilities [

5,

6].

Corrigan and Watson, in 2002, proposed a social-cognitive model of public stigma. The model involves three components—stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination—and demonstrates a stigma process. At the beginning, stereotypes are formed as an efficient means of categorizing information about social groups and represent a collective agreement regarding groups of persons. Stereotypes related to mental illness include dangerousness, character weakness, and incompetence. Persons who endorse these negative stereotypes would be prejudiced and generate negative emotional responses like anger or fear. Finally, stereotypes (the cognitive response) and prejudice (the emotional response) lead to discrimination (the behavioral magnification) [

7].

The negative attitudes and viewpoints that many health professionals hold toward individuals with mental illnesses shape the quality of care that clients receive, and, ultimately, the quality of life of clients [

8]. Stigmatizing behaviours and attitudes generate barriers such as “delays in help-seeking, discontinuation of treatment, suboptimal therapeutic relationships, patient safety concerns, and poorer quality mental and physical care” [

1] (p. 112).

In 2006, the first Canadian national mental health report was released by the Standing Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology. In

Out of the Shadows at Last: Transforming Mental Health, Mental Illness, and Addiction Services in Canada, the committee revealed a concern that healthcare professionals play a role in the perpetuation of mental illness stigma and can sabotage the process of recovery from mental illness by making negative assumptions and discriminating against those who have already been stigmatized by society [

9]. There is a growing concern among mental health stigma researchers that healthcare professionals lack the educational background and awareness to work appropriately with individuals with mental illnesses [

10].

While the problem of mental health stigma in healthcare professionals is apparent in the literature, the attitudes to and perceptions of mental illnesses by students in healthcare education programs are less apparent. Findings from Ogunsemi and colleagues [

11] support these concerns. Responses were collected from final year medical students: one group answered a questionnaire that included a vignette with a psychiatric label attached, and a second group answered a questionnaire that included the same vignette with no psychiatric label. The study indicated that students showed negative attitudes toward individuals identified with a mental illness, and sought to maintain a significant social distance from individuals with this label [

11]. A study conducted by Mukherjee and colleagues (2002) found that doctors and medical students shared similar negative attitudes toward individuals with mental illnesses, specifically individuals with schizophrenia, drug addiction, and alcohol addiction. More than 50% of the doctors and medical students surveyed felt that people with schizophrenia and drug and alcohol addictions were dangerous and unpredictable [

12]. Another study revealed that healthcare providers stigmatized pregnant depressed women; particularly, some healthcare professionals were nervous around women with antenatal depression [

13].

In contrast, not all research found negative attitudes and/or behaviours in healthcare professionals and students toward individuals with mental illnesses. For instance, mental health professionals have been found to hold a more positive attitude than the general public toward people with mental illnesses [

8]. However, it was determined that mental health professionals tend to stereotype individuals with mental illnesses, especially individuals with schizophrenia, whom they consider to be particularly dangerous [

8]. Henderson, et al., (2014) found that contact with people with mental illnesses was positively associated with more supportive attitudes in practitioners toward the civil rights of individuals with mental illnesses [

14]. Another study demonstrated that primarily positive attitudes were held by entry-level physiotherapy undergraduate students toward psychiatry and individuals with mental illness [

15].

Quantitative scales and assessments currently dominate the literature regarding the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours of healthcare professionals and students toward mental illness. There is less focus on healthcare students’ perspectives than on healthcare professionals’ perspectives, and research articles considering this topic primarily focus on the nursing discipline, with less emphasis on other healthcare professions. The present study concentrates on the knowledge, attitudes, and behavioural responses of various healthcare students toward individuals with mental illnesses, since students represent the future quality of care received by such individuals. A qualitative inquiry will allow us to gather information while exploring context, recurring themes, and unforeseen findings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

Qualitative research systematically collects and interprets material derived from conversations and observations. It is used to explore meanings of social phenomena as experienced by individuals in certain contexts [

16]. This study used a generic qualitative approach—Qualitative Description [

17]—which focuses on exploring how people interpret their experiences and the meaning they attribute to their experiences. The research methods within Qualitative Description are inductive and produce a low-inference description of a phenomenon in order to remain closer to the original data. Thematic analysis [

18] was used to analyze and identify patterns and meaning and themes in the knowledge, attitudes, and behavioural responses of healthcare students in the context of mental illness. This research design is flexible, summarizes key qualities in a descriptive dataset, and provides insights into the data.

2.2. Participant Recruitment

Two students from each of nine healthcare programs at a Canadian University were recruited to participate in the interviews, for a total of eighteen students. These programs included: Dental Hygiene/Surgery, Dietetics/Nutrition, Medicine, Nursing, Occupational Therapy, Pharmacy, Physical Therapy, Psychology, and Speech-Language Pathology. Health science programs not considered to be in direct contact with clients with mental illnesses were not included in the study. Recruitment posters were released in approved and selected areas. All students interested in participating in the study contacted the researcher via email. Participants were chosen based on establishing the most variability (e.g., gender, year of study) in the sample population.

2.3. Data Collection

Participants in the study were interviewed to understand the context behind the knowledge, attitudes, and behavioural responses that healthcare students have toward mental illnesses. The interview procedure was semi-structured, involving a set of predetermined questions.

The study was approved by a University Research Ethics Board (Study ID: Pro00084418). Two students from each discipline were interviewed by the researcher separately. Each participant filled out a consent form and read information about the research study before the interview began. The interview lasted for a maximum of 60 min and followed the planned interview questions and follow up questions. Recruitment was planned to continue if the data from the initial eighteen interviews did not reach code saturation and meaning saturation.

During the interview, participants were asked a variety of questions about their experiences and opinions with respect to various elements of the project. They were asked questions regarding societal perceptions of mental illness and whether or not they believe mental illness stigma to be a concern in the community. The interview protocol included seven groups of questions: (1) What type of contact and experiences, in your personal life, have you had with individuals who have mental health issues? (2) What is your understanding of mental illnesses? (3) How would you describe your degree of compassion and empathy towards individuals with mental illnesses? (4) What would you do if you had a mental illness? (5) Since starting your healthcare program, what type of experience(s) have you had working with individuals with mental illnesses? (6) Since starting your healthcare program, what type of information have you received in your academic learning regarding mental illness? And (7) Based on your overall personal and academic experiences and knowledge of mental illnesses, how would you feel working with individuals who have mental illness? Participants were informed that there were no right or wrong answers. All interviews were audio recorded for data analyses.

2.4. Data Analysis

All interview data were transcribed verbatim. The analyses involved structured coding procedures and thematic characterizations of the coded segments [

19]. After reading through the text, the lead researcher (TR) and the research supervisor (SC) analyzed the transcriptions using the coding reliability approach of thematic analysis [

18]. Initial coding was performed by TR and SC independently, using both inductive and deductive approaches [

20]. Relevant codes were identified, and a structured codebook was developed following the procedures outlined by MacQueen et al. [

21]. The codebook included detailed definitions, typical exemplars, atypical exemplars, and marginal/irrelevant examples from the texts to illustrate the range of meanings assigned to themes. After the initial coding was complete, the core analysis included code categorization and thematic comparison [

19]. Both researchers determined the final coding through consensus, reviewed the patterns of shared meanings, and categorized overlapping themes into a practicable list of defined themes.

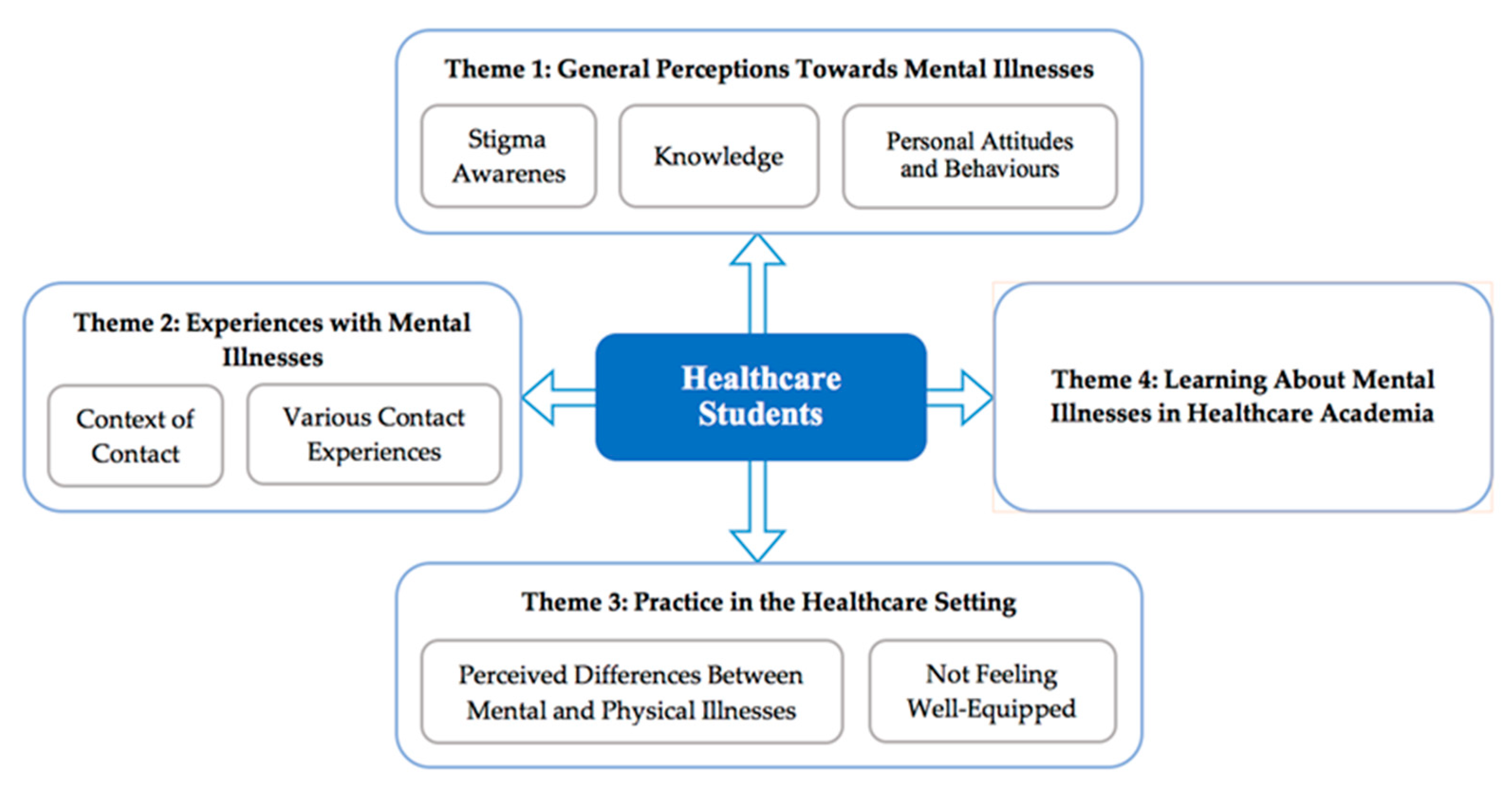

4. Discussion

This study of healthcare students’ experiences with individuals with mental illnesses increases our understanding of current healthcare programs in the sector. Healthcare student participants had a basic understanding of mental illnesses and recognized an assortment of mental illness origins and treatments. Participants generally held positive attitudes toward individuals with mental illnesses, however, several stigmatizing perceptions were evident in the study findings.

Participants identified positive and stigmatizing perceptions of mental illnesses currently held by society, although some participants acknowledged that mental illness stigmatization has lessened in recent years. No mention or acknowledgement of any personal stigma was made by the students in the study. Although most of the participants did not share society’s stigmatizing views of mental illness, some of the participants presented fearful, uncomfortable, and stigmatizing attitudes toward mental illnesses. The finding that some healthcare students hold stigmatizing attitudes toward individuals with mental illnesses is not new. The healthcare literature documents stigmatizing attitudes and behaviours across the healthcare spectrum [

1]. Our findings are novel with respect to the absence in some healthcare students of acknowledged personal stigmatizing attitudes toward individuals with mental illnesses.

Interestingly, social media influences human interaction in the era of technology. In this study, the phenomenon that people use social media to post their mental health problems was somehow interpreted as an attempt to garner pity or attention. This interpretation may potentially be a type of stigma. The interaction between users of social media and their emotional experience is complex [

22]. As frequently posting positive or negative effects on social media has been associated with depression [

23], it is important to further understand the theoretical mechanism of social media posts—the difference between a call for help and a plea for attention—and its association with stigmatized attitudes.

Half of the participants in this study had experienced a mental illness themselves. This proportion is considerably higher than the Canadian national average of 20%, thus there is a question of whether there is a higher amount of mental illness among healthcare students or whether participants who have experienced a mental illness themselves or in others were simply more motivated to enroll in this study [

24]. Other studies have shown a high prevalence of mental illness among workers in the healthcare industry [

25]. However, literature considering the levels of mental illness apparent in healthcare students was not found at this time. The presence of mental illness among healthcare students and professionals is important, because healthcare providers are responsible for providing competent and safe care to the public [

26]. Interestingly, participants who had lived experiences of mental illness held less of an “us and them” discrepancy between themselves and people with mental health disorders. Thus, having self-experience with mental illness might decrease mental illness stigmatization and foster empathy and understanding between healthcare workers and mentally ill individuals.

All participants in this study, except for one, had experienced direct contact with mental illnesses outside their healthcare practice. The majority of these participants mentioned being positively impacted through such contact, and thus had an increased awareness of the problems mental illnesses entail. This is consistent with findings that direct contact experiences with individuals with mental illnesses can help to reduce stigma [

27]. Of note, some participants discussed challenges they faced when a loved one experienced mental illness, such as stress on the caregiver and a negative impact on family relations. This is consistent with results in the literature that noted similar stressors and emotional concerns among individuals providing support and care to a loved one with a mental illness [

28]. On the other hand, healthcare students who, in their private life, have experienced difficulties with individuals with mental illnesses may have a negative outlook toward mental health, that affects their behaviour in their healthcare practice.

When discussing the differences between treating mental versus physical illness, most participants stressed the complexity of treating mental illness and the stigmatization that mental illness faces in society. The findings regarding participants’ stigma toward mental illness versus their nonstigmatic approaches to physical illness are consistent with the findings in other studies [

29,

30]. For instance, Corrigan and colleagues [

29] determined that mental disorders are often more stigmatized than physical disorders. The present study suggested that these perceptions stemmed from the fact that mental illness is often more difficult to treat, more invisible, and more long-lasting than physical illness. Such perceptions might lead healthcare students to avoid working in a mental healthcare setting in future.

Most participants reported that their healthcare program did not provide sufficient mental illness education to adequately prepare them to provide appropriate support for individuals with mental illnesses. This echoes Tognazzini and colleagues’ [

10] finding that healthcare professionals may be deficient in mental illness education and awareness. Many participants commented that, although they did not currently feel adequately prepared, they hoped to receive more mental health education and experience during their program. Healthcare programs can help to improve students’ mental health education by delivering mental health training earlier on in the program and throughout it, providing more integration with clients with mental illnesses, clarifying the scope of the discipline when working with individuals with mental illnesses, and demystifying/destigmatizing mental illness as an “impossible” illness to work with. According to the Mental Health Commission of Canada [

26], healthcare workers are 1.5 times more likely than workers in other sectors to require time off work due to an illness or disability. Therefore, healthcare students should be taught not only how to work with various mental illnesses, but also how to develop appropriate coping strategies for their own mental health before entering the workforce. The health and well-being of healthcare professionals can assist in helping to reduce stigma in the healthcare system and would have a positive impact on staff and patient safety [

1].

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

The small-scale qualitative design (i.e., a total of 18 participants in a single university) limits the generalizability of the findings in terms of their being representative of healthcare student populations and healthcare educational programs. However, the diversity of healthcare student participants recruited was a strength of the study. Participant diversity was based on program, gender, and year of study. Participant biases included acquiescence bias and social desirability bias. To minimize the effects of these biases on the results, questions were open-ended, and participants were informed that there was no right or wrong answer to any question and were told that they could advise the interviewer if they did not want to answer a question.

The main causes of researcher bias would be leading questions and wording biases. The learning curve of the researcher in training (TR) must be considered in the conduction of interviews. TR was trained by an experienced researcher (SC) to avoid using leading questions and to transcribe participants’ answers verbatim; however, mastery of these skills requires practice and experience.

4.2. Implications for Future Research

This study had a small sample size (two participants) taken from each of the nine faculties. Therefore, differences between the healthcare programs were not analyzed in this study. Future research could use variations between disciplines to inform specific mental health education in healthcare programs. An in-depth analysis of the mental health education taught and the experiences (or lack thereof) encountered in each faculty would help to determine whether there is a correlation between healthcare program teachings and the knowledge, attitudes, and behavioural responses of healthcare students.

Future research could find interventions and strategies that reduce the stigma related to mental illness among students in healthcare programs. For example, contact-based education, where healthcare students engage with individuals with mental illness(es) [

31], would acclimatize students and reduce the mystery of the diseases.