Exploring Perceptions of the Work Environment among Psychiatric Nursing Staff in France: A Qualitative Study Using Hierarchical Clustering Methods

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Setting and Population

2.2. Study Period and Sampling

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis and Use of IRaMuTeQ Software

2.5. Ethics and Informed Consent

3. Results

3.1. Subsection

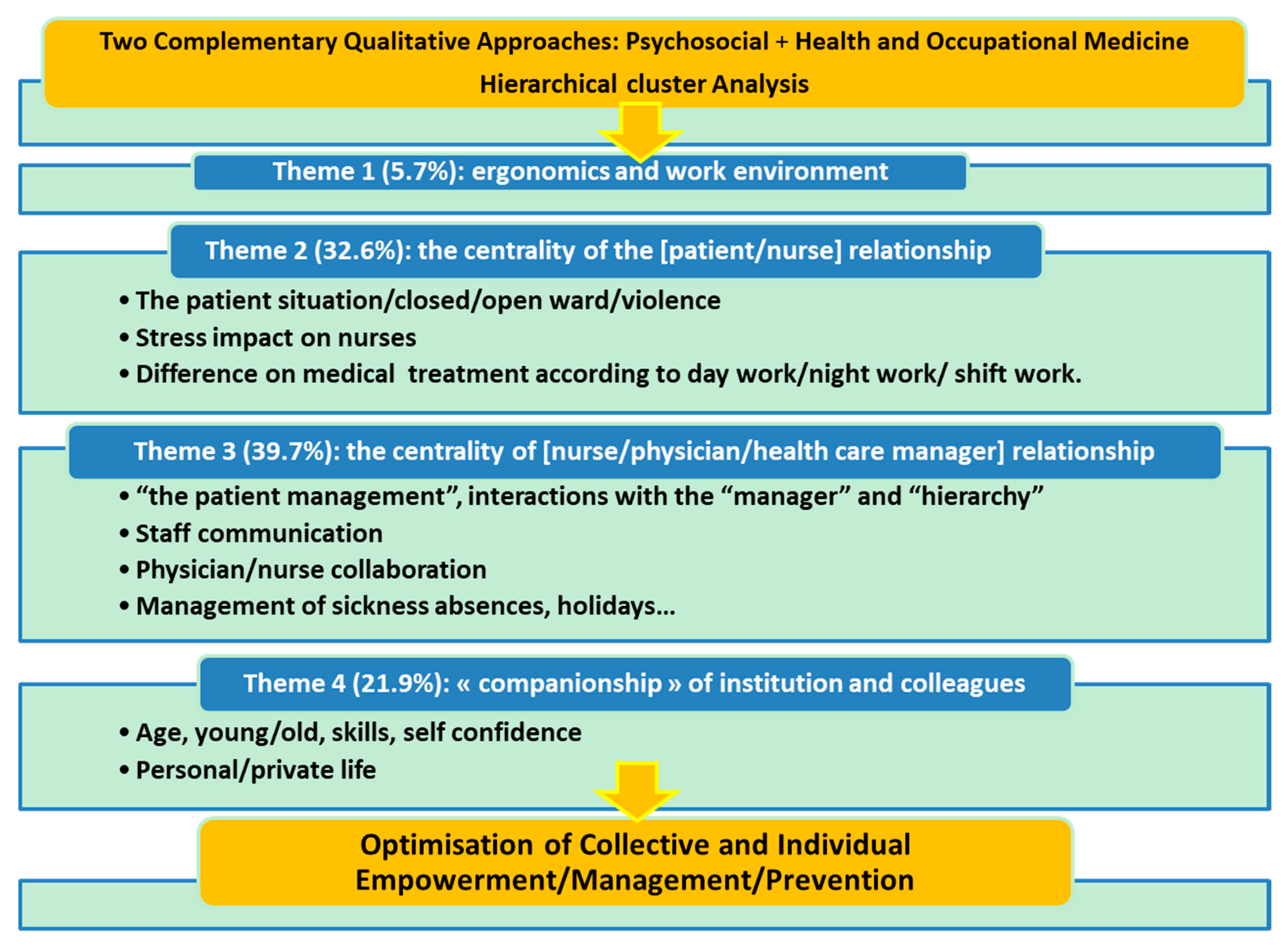

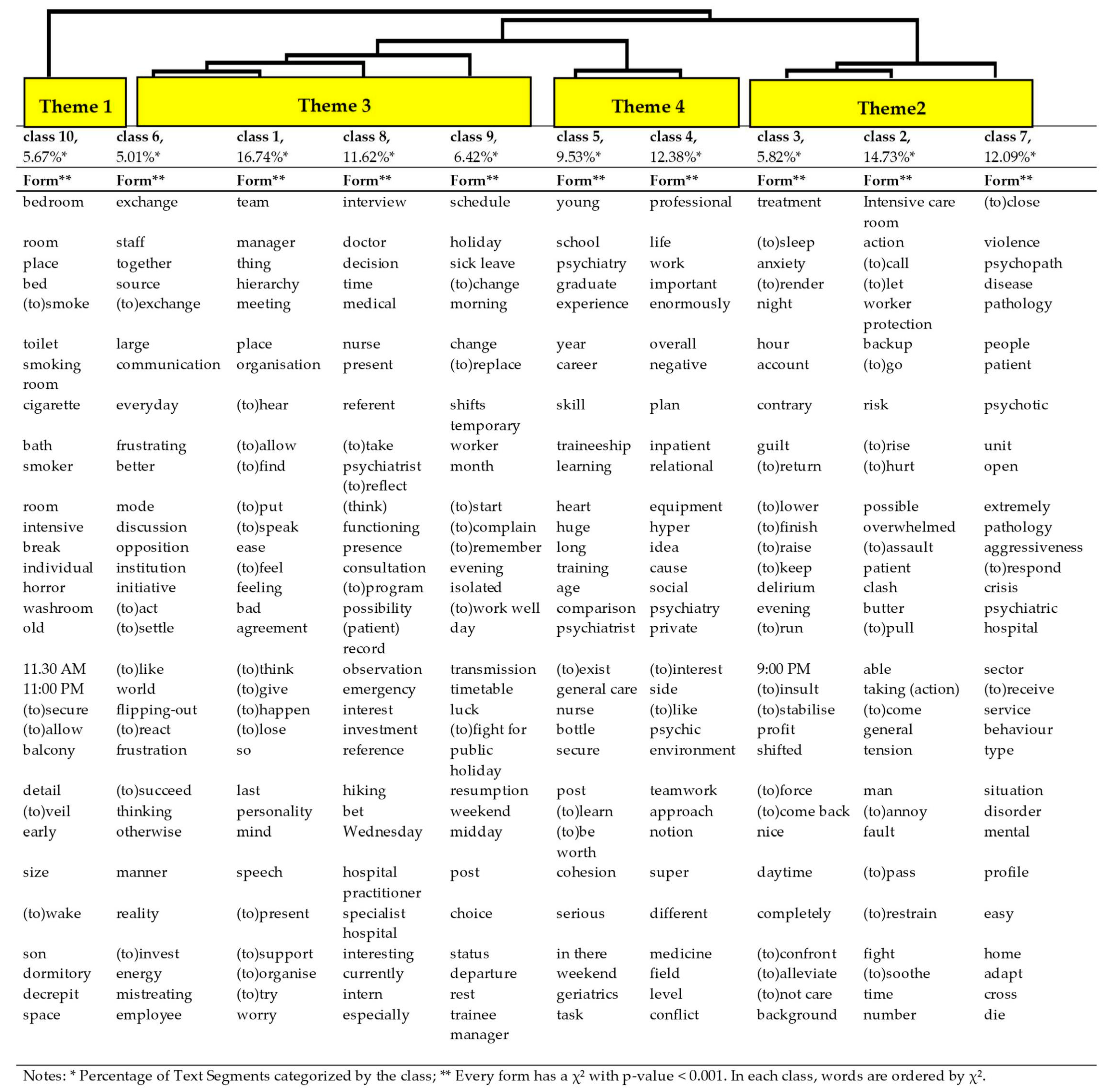

3.1.1. Definition of Classes by Theme and Hierarchical Structure

3.1.2. Theme 1

3.1.3. Theme 2 (3 Classes/32.6% of TS)

3.1.4. Theme 3 (4 Classes/39.7% of TS)

3.1.5. Theme 4 (2 Classes/21.9% of TS)

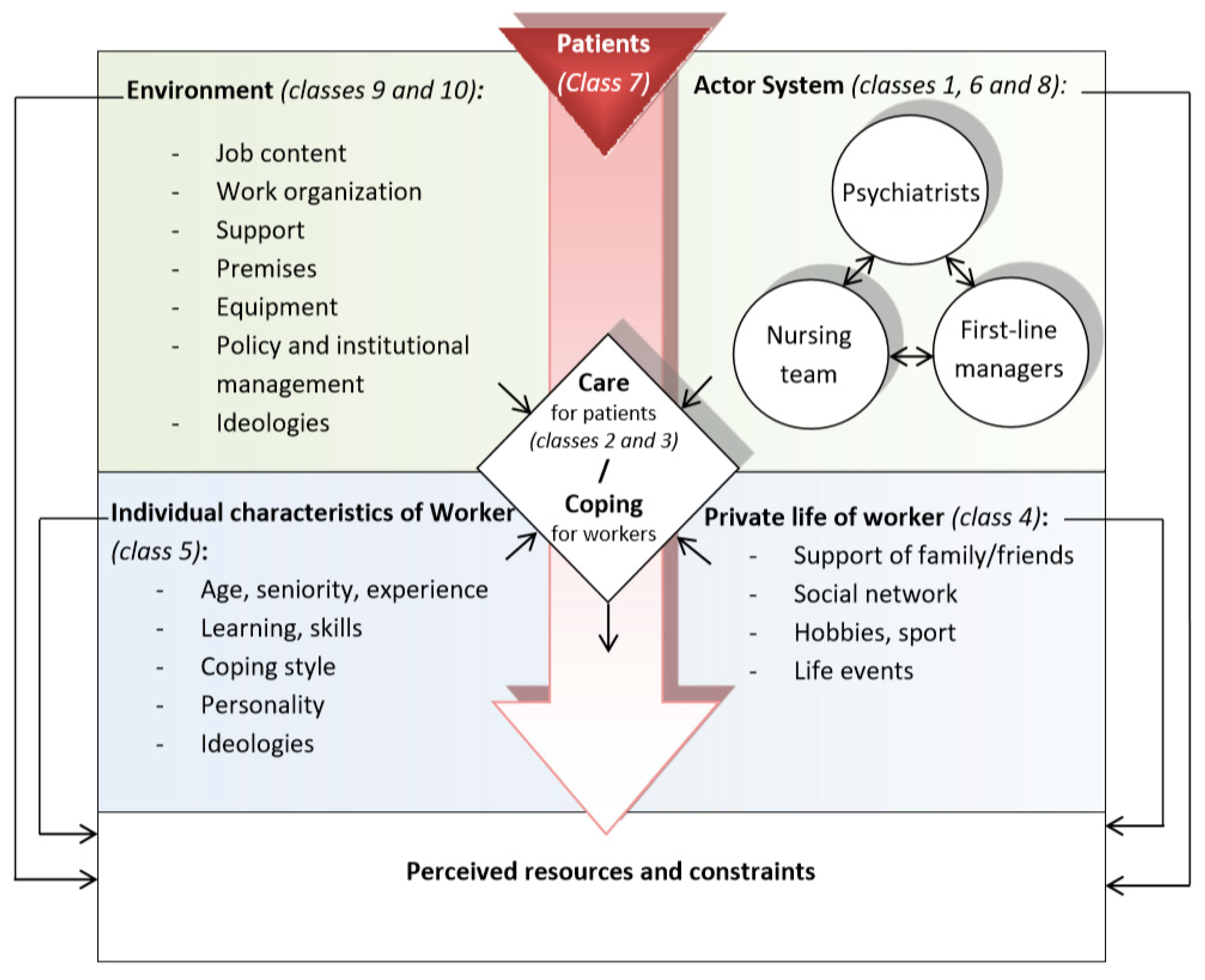

4. Discussion

4.1. Ergonomics and Work Environment

4.2. “Chemical and Institutional Care” for Patients

4.3. Collective: An Answer to Meet Work Demands

4.4. Actors System and Processes of Collective Efficiency

4.5. Organizational Support

4.6. Personal Coping, Impact on Personal Life

4.7. Overall Structure

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Karasek, R. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Adm. Sci. Q. 1979, 24, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1996, 1, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, J.S. Toward an understanding of inequity. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1963, 67, 422–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, J.S. Inequity in social exchange. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1965, 2, 267–299. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin, K.L.R.; White, R.K. Patterns of aggressive behavior in experimentally created social climates. J. Soc. Psychol. 1939, 10, 271–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.K.; Lippitt, R. Autocracy and Democraty: An Experimental Inquiry; Harper & Brothers: New York, NY, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Dewa, C.S.; Lesage, A.; Goering, P.; Craveen, M. Nature and prevalence of mental illness in the workplace. Healthc. Pap. 2004, 5, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimaki, M.; Ferrie, J.E.; Head, J.; Shipley, M.J.; Vahtera, J.; Marmot, M.G. Organisational justice and change in justice as predictors of employee health: The Whitehall II study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2004, 58, 931–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stansfeld, S.; Candy, B. Psychosocial work environment and mental health-a metaanalytic review. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2006, 32, 443–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonde, J.P. Psychosocial factors at work and risk of depression: A systematic review of the epidemiological evidence. Occup. Environ. Med. 2008, 65, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyberg, A. The Impact of Managerial Leadership on Stress and Health among Employees; Jarolinska Institutet: Stockholm, Sweden, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Elovainio, M.; Kivimaki, M.; Puttonen, S.; Lindholm, H.; Pohjonen, T.; Sinervo, T. Organisational injustice and impaired cardiovascular regulation among female employees. Occup. Environ. Med. 2006, 63, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimaki, M.; Virtanen, M.; Elovainio, M.; Kouvonen, A.; Vaananen, A.; Vahtera, J. Work stress in the etiology of coronary heart disease-a meta-analysis. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2006, 32, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimaki, M.; Ferrie, J.E.; Shipley, M.; Gimeno, D.; Elovainio, M.; de Vogli, R.; Vahtera, J.; Marmot, M.G.; Head, J. Effects on blood pressure do not explain the association between organizational justice and coronary heart disease in the Whitehall II study. Psychosom. Med. 2008, 70, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eller, N.H.; Netterstrom, B.; Gyntelberg, F.; Kristensen, T.S.; Nielsen, F.; Steptoe, A.; Theorell, T. Work-related psychosocial factors and the development of ischemic heart disease: A systematic review. Cardiol. Rev. 2009, 17, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kivimaki, M.; Head, J.; Ferrie, J.E.; Singh-Manoux, A.; Westerlund, H.; Vahtera, J.; Leclerc, A.; Melchior, M.; Chevalier, A.; Alexanderson, K.; et al. Sickness absence as a prognostic marker for common chronic conditions: Analysis of mortality in the GAZEL study. Occup. Environ. Med. 2008, 65, 820–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, H.L.; Nigam, J.A.S.; Sauter, S.L.; Chosewood, L.C.; Schill, A.L.; Howard, J. Total Work. Health; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Portoghese, I.; Galletta, M.; Burdorf, A.; Cocco, P.; D’Aloja, E.; Campagna, M. Role Stress and Emotional Exhaustion among Health Care Workers: The Buffering Effect of Supportive Coworker Climate in a Multilevel Perspective. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 59, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Labour Organization (ILO). Workplace Stress: A Collective Challenge; World Safety Day; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 9789221306429. [Google Scholar]

- Jarman, L.; Martin, A.; Venn, A.; Otahal, P.; Taylor, R.; Teale, B.; Sanderson, K. Prevalence and correlates of psychological distress in a large and diverse public sector workforce: Baseline results from Partnering Healthy@ Work. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, K.; Andrews, G. Common mental disorders in the workforce: Recent findings from descriptive and social epidemiology. Can. J. Psychiatry 2006, 5, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, L.H.; Johnson, J.; Watt, I.; Tsipa, A.; O’Connor, D.B. Healthcare staff wellbeing, burnout, and patient safety: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, E.M.; Daly, J.W.; Hancock, K.M.; Bidewell, J.; Johnson, A.; Lambert, V.A.; Lambert, C.E. The relationships among workplace stressors, coping methods, demographic characteristics, and health in Australian nurses. J. Prof. Nurs. 2006, 22, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaha, E.; Lal, S.; Samaha, N.; Wyndham, J. Psychological, lifestyle and coping contributors to chronic fatigue in shift-worker nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2007, 59, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompili, M.; Rinaldi, G.; Lester, D.; Girardi, P.; Ruberto, A.; Tatarelli, R. Hopelessness and suicide risk emerge in psychiatric nurses suffering from burnout and using specific defense mechanisms. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2006, 20, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Leo, D.; Magni, G.; Vallerini, A.; Dal Palù, C. Assessment of anxiety and depression in general and psychiatric nurses. Psychol. Rep. 1983, 52, 335–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tummers, G.E.; Janssen, P.P.; Landeweerd, A.; Houkes, I. A comparative study of work characteristics and reactions between general and mental health nurses: A multi-sample analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2001, 36, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishi, Y.; Kurosawa, H.; Morimura, H.; Hatta, K.; Thurber, S. Attitudes of Japanese nursing personnel toward patients who have attempted suicide. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2011, 33, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, C.; Nakamura, H.; Akasaka, H.; Yagi, J.; Koeda, A.; Takusari, E.; Otsuka, K.; Sakai, A. The impact of inpatient suicide on psychiatric nurses and their need for support. BMC Psychiatry 2011, 1, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, M.; Tsukano, K.; Muraoka, M.; Kaneko, F.; Okamura, H. Psychological impact of verbal abuse and violence by patients on nurses working in psychiatric departments. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2006, 60, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borritz, M.; Rugulies, R.; Bjorner, J.B.; Villadsen, E.; Mikkelsen, O.A.; Kristensen, T.S. Burnout among employees in human service work: Design and baseline findings of the PUMA study. Scand. J. Public Health 2006, 34, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, J.H.; Li, R.H.; Yu, H.Y.; Chen, S.H. Relationships among self-esteem, job adjustment and service attitude amongst male nurses: A structural equation model. J. Clin. Nurs. 2011, 20, 864–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Del-Río, B.; Solanes-Puchol, Á.; Martínez-Zaragoza, F.; Benavides-Gil, G. Stress in nurses: The 100 top-cited papers published in nursing journals. J. Adv. Nurs. 2018, 74, 1488–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.V.; Hall, E.M.; Theorell, T. Combined effects of job strain and social isolation on cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality in a random sample of the Swedish male working population. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 1989, 15, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Caplan, R.D.; Harrison, R.V. Person-environment fit theory: Conceptual foundations, empirical evidence, and directions for future research. In Theories of Organizational Stress; Cooper, C.L., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1998; pp. 28–67. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, J. A Themeomy of Organizational Justice Theories. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1987, 12, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häusser, J.A.; Mojzisch, A.; Niesel, M.; Schulz-Hardt, S. Ten years on: A review of recent research on the Job Demand–Control (-Support) model and psychological well-being. Work Stress 2010, 24, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.; Osborn, D.P.J.; Araya, R.; Wearn, E.; Paul, M.; Stafford, M.; Wood, S.J. Morale in the English mental health workforce: Questionnaire survey. Br. J. Psychiatry 2012, 201, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lasalvia, A.; Bonetto, C.; Bertani, M.; Bissoli, S.; Cristofalo, D.; Marrella, G.; Ruggeri, M. Influence of perceived organisational factors on job burnout: Survey of community mental health staff. Br. J. Psychiatry 2009, 195, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, D.A.; Bee, P.; Barkham, M.; Gilbody, S.M.; Cahill, J.; Glanville, J. The prevalence of nursing staff stress on adult acute psychiatric in-patient wards: A systematic review. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2006, 41, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, T. Where are the hypotheses when you need them? Br. J. Psychiatry 2012, 201, 178–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.H.; Patrician, P.A. Measuring organizational traits of hospitals: The Revised Nursing Work Index. Nurs. Res. 2000, 49, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosser, D.; Johnson, S.; Kuipers, E.; Szmukler, G.; Bebbington, P.; Thornicroft, G. Perceived sources of work stress and satisfaction among hospital and community mental health staff, and their relation to mental health, burnout and job satisfaction. J. Psychosom. Res. 1997, 43, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossberg, J.I.; Friis, S. Patients’ and staff’s perceptions of the psychiatric ward environment. Psychiatr. Serv. 2004, 55, 798–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, J.; Knizek, B.L.; Hjelmeland, H. Mental Health Nurses’ Experiences of Caring for Suicidal Patients in Psychiatric Wards: An Emotional Endeavor. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2017, 31, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, M.A.R.; Wall, M.L.; De Morais Chaves huler, A.C.; Lowen, I.M.V.; Peres, A.M. The use of IRaMuTeQ software for data analysis in qualitative research. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2018, 52, e03353. [Google Scholar]

- Reinert, M. Alceste. Une méthodologie d’analyse des données textuelles et une application: Aurelia De Gerard De Nerval. Bull. Méthodol. Sociol. 1990, 26, 24–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broc, G.; Gana, K.; Denost, Q.; Quintard, B. Decision-making in rectal and colorectal cancer: Systematic review and qualitative analysis of surgeons’ preferences. Psychol. Health Med. 2017, 22, 434–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierres, L.S.; Santos, J.L.G.D.; Peiter, C.C.; Menegon, F.H.A.; Sebold, L.F.; Erdmann, A.L. Good practices for patient safety in the operating room: nurses’ recommendations. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2018, 71, 2775–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowen, I.M.V.; Peres, A.M.; Ros, C.D.; Poli, P.; Neto Faoro, N.T. Innovation in nursing health care practice: Expansion of access in primary health care. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2017, 70, 898–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Galindo Neto, N.M.; Carvalho, G.C.N.; Castro, R.C.M.B.; Caetano, J.Á.; Santos, E.C.B.D.; Silva, T.M.D.; Vasconcelos, E.M.R. Teachers’ experiences about first aid at school. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2018, 71, 1678–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M.A.; Silva, D.R.A.; De Sousa Ibiapina, A.R.; Soares, E.; Silva, J. Mental illness and its relationship with work: A study of workers with mental disorders. Rev. Bras. Med. Trab. 2018, 16, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochmann, J. Histoire de la Psychiatrie, 3rd ed.; Presses Universitaires de France—PUF: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chaperot, C.; Pisani, C.; Goullieux, E.; Guedj, P. Réflexions sur le cadre thérapeutique et l’institution: Médiatisation et caractère partiel. L’Évolution Psychiatr. 2003, 68, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.C.; Cheng, Y.; Tsai, P.J.; Lee, S.S.; Guo, Y.L. Occupational stress in nurses in psychiatric institutions in Taiwan. J. Occup. Health 2005, 47, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripodi, D.; Roedlich, C.; Laheux, M.A.; Longuenesse, C.; Roquelaure, Y.; Lombrail, P.; Geraut, C. Stress perception among employees in a French University Hospital. Occup. Med. 2012, 62, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, L.; Allan, T.; Simpson, A.; Jones, J.; Whittington, R. Morale is high in acute inpatient psychiatry. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2009, 44, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmutz, J.; Manser, T. Do team processes really have an effect on clinical performance? A systematic literature review. Br. J. Anaesth. 2013, 110, 529–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spreitzer, G.M. An empirical test of a comprehensive model of intrapersonal empowerment in the workplace. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1995, 23, 601–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, J.I.; Cummings, G.; Smith, D.L.; Olson, J.; Anderson, L.; Warren, S. The relationship between structural empowerment and psychological empowerment for nurses: A systematic review. J. Nurs. Manag. 2010, 18, 448–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolley, A.W.; Chabris, C.F.; Pentland, A.; Hashmi, N.; Malone, T.W. Evidence for a Collective Intelligence Factor in the Performance of Human Groups. Science 2010, 330, 686–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, E.; Cooke, N.J.; Rosen, M.A. On Teams, Teamwork, and Team Performance: Discoveries and Developments. Hum. Factors 2008, 50, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoli, L.; Sotgiu, G.; Magnavita, N. Evidence-based approach for continuous improvement of occupational health. Epidemiol. Prev. 2015, 39, 81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Copello, F.; Garbarino, S.; Messineo, A.; Campagna, M.; Durando, P. Collaborators.Occupational Medicine and Hygiene: Applied research in Italy. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2015, 56, E102–E110. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Categories | n |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 23–29 | 11 |

| 30–40 | 14 | |

| 41–65 | 12 | |

| Gender | ||

| Men | 7 | |

| Women | 30 | |

| Psychiatry sector | ||

| a | 6 | |

| b | 10 | |

| c | 5 | |

| d | 7 | |

| e | 5 | |

| s | 4 | |

| Unit type | ||

| Closed | 16 | |

| Open | 17 | |

| Variable | 4 | |

| Working time | ||

| Day | 30 | |

| Night | 7 | |

| Seniority in unit (years) | ||

| 0–1 | 10 | |

| 2–4 | 10 | |

| 4–9 | 9 | |

| 10–28 | 7 |

| Class | Text Segments (TS) |

|---|---|

| Class 1 | I asked my manager to set up a team meeting, because I wanted things to be said, in order to improve communication. |

| In clinical meetings, we talk about patient care, and I’ve already seen managers talk about things they know nothing about. | |

| I expect the manager to be the nursing team spokesman, when things like that happen. | |

| Class 2 | I dodged his blows, I was lucky I wasn’t hit, and lots of colleagues came to help; the patient went to the CSI. |

| When a patient who clashes arrives in the unit, we’re going to think about protecting the other patients, protecting the patient, to call for backup. | |

| An intensive care room is provided, we call enough men and then we accompany the patient to the room, usually we mustn’t touch the patient. | |

| Class 3 | You have to give treatments to patients who don’t need them, but as they can’t sleep because of another’s agitation. |

| There are more anxieties in the evening so it’s always harder to manage, but patients are well managed during the daytime, so they are generally calm in the evening. | |

| A more sedative treatment that acts on anxiety, after a background treatment like risperidone… Then we mustn’t abrade too much as they’re not well afterwards. | |

| Class 4 | Outside it will be family, friends, spouse, sport, music … life goes beyond work so that’s important. |

| I think that one day all psychiatric nurses need to go by themselves to verbalize things to a psychologist or a psychiatrist. | |

| In the evening I go home and I read a book or watch a series and it helps me to return to my private life and I manage better now. | |

| Class 5 | You’re a recent graduate, you’ve had a general training, you’re not trained in psychiatry and you begin in psychiatry … it all has an effect. |

| You learn that with experience, the ability to protect yourself, you can’t learn that at school. | |

| As I’m a recent graduate, maybe I can’t step back, it’s experience that lets you stand back like my colleagues. | |

| Class 6 | He’ll have to listen to what you say, there’s an exchange that’s necessary; it’s more about communication than I tell you what to do. |

| Our team gets along well, we communicate, there are exchanges, we can share our doubts, discuss. | |

| The more meetings we have, the more time we have together to exchange information directly. | |

| Class 7 | In a closed unit it’s really violence, or crisis, managing the crisis in the psychotic patient. |

| It’s a serious disease, when psychotic delusional people are in an acute state of suffering, they don’t have access to reasoning. | |

| People who have behavioral disorders on the streets and go to prison from time to time … They have violent or even suicidal profiles. | |

| Class 8 | Relationship with doctors, I find it interesting when you have doctors who are there and who take the time with you, when nurses go to the medical interviews. |

| Where there were no nursing interviews, where the word of the nurse was not listened to. | |

| The doctors, or the head of service, give us a lot of autonomy in decision-making. | |

| Class 9 | We make changes, we arrive on holiday we’re exhausted, and we tell ourselves that evening-morning, nights-days, ultimately it’s tiring. |

| There are institutional demands for schedule change that don’t go with our work organization in psychiatry. | |

| It was a schedule that was quite difficult with many days of isolated rest. | |

| Class10 | So everyone has a bathroom, there are two rooms with 2 beds but with a bathroom so it’s still good. |

| It’s quite scary I think to arrive in a place like that, such as intensive care rooms, it’s really the strict minimum. | |

| This patient, they took him out of the intensive care room, put him in a room although he’s still a man from prison and we had minors in the unit. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cougot, B.; Fleury-Bahi, G.; Gauvin, J.; Armant, A.; Durando, P.; Dini, G.; Gillet, N.; Moret, L.; Tripodi, D. Exploring Perceptions of the Work Environment among Psychiatric Nursing Staff in France: A Qualitative Study Using Hierarchical Clustering Methods. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17010142

Cougot B, Fleury-Bahi G, Gauvin J, Armant A, Durando P, Dini G, Gillet N, Moret L, Tripodi D. Exploring Perceptions of the Work Environment among Psychiatric Nursing Staff in France: A Qualitative Study Using Hierarchical Clustering Methods. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(1):142. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17010142

Chicago/Turabian StyleCougot, Baptiste, Ghozlane Fleury-Bahi, Jules Gauvin, Anne Armant, Paolo Durando, Guglielmo Dini, Nicolas Gillet, Leila Moret, and Dominique Tripodi. 2020. "Exploring Perceptions of the Work Environment among Psychiatric Nursing Staff in France: A Qualitative Study Using Hierarchical Clustering Methods" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 1: 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17010142

APA StyleCougot, B., Fleury-Bahi, G., Gauvin, J., Armant, A., Durando, P., Dini, G., Gillet, N., Moret, L., & Tripodi, D. (2020). Exploring Perceptions of the Work Environment among Psychiatric Nursing Staff in France: A Qualitative Study Using Hierarchical Clustering Methods. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(1), 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17010142