Can Forum Play Contribute to Counteracting Abuse in Health Care? A Pilot Intervention Study in Sri Lanka

Abstract

:1. Introduction

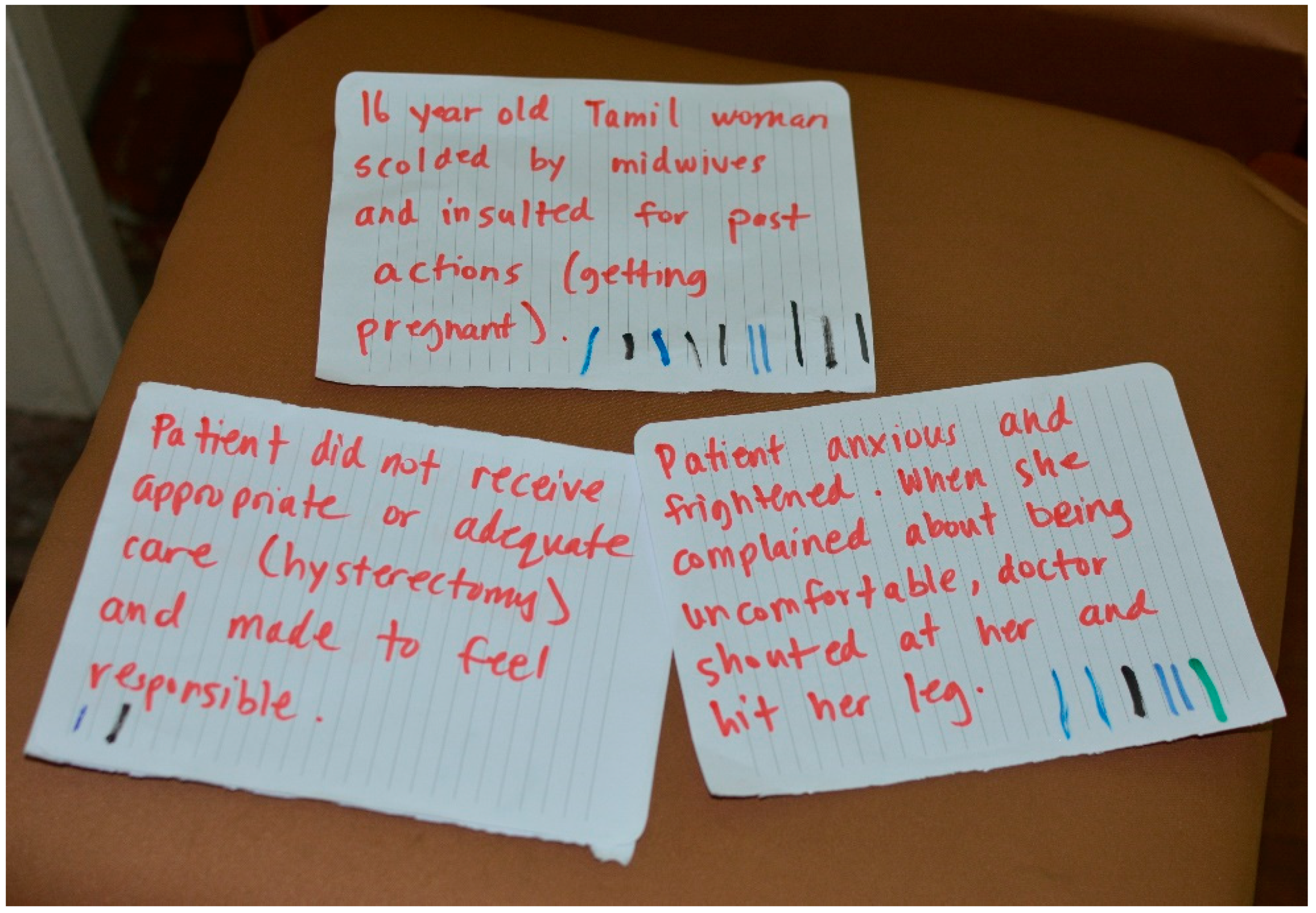

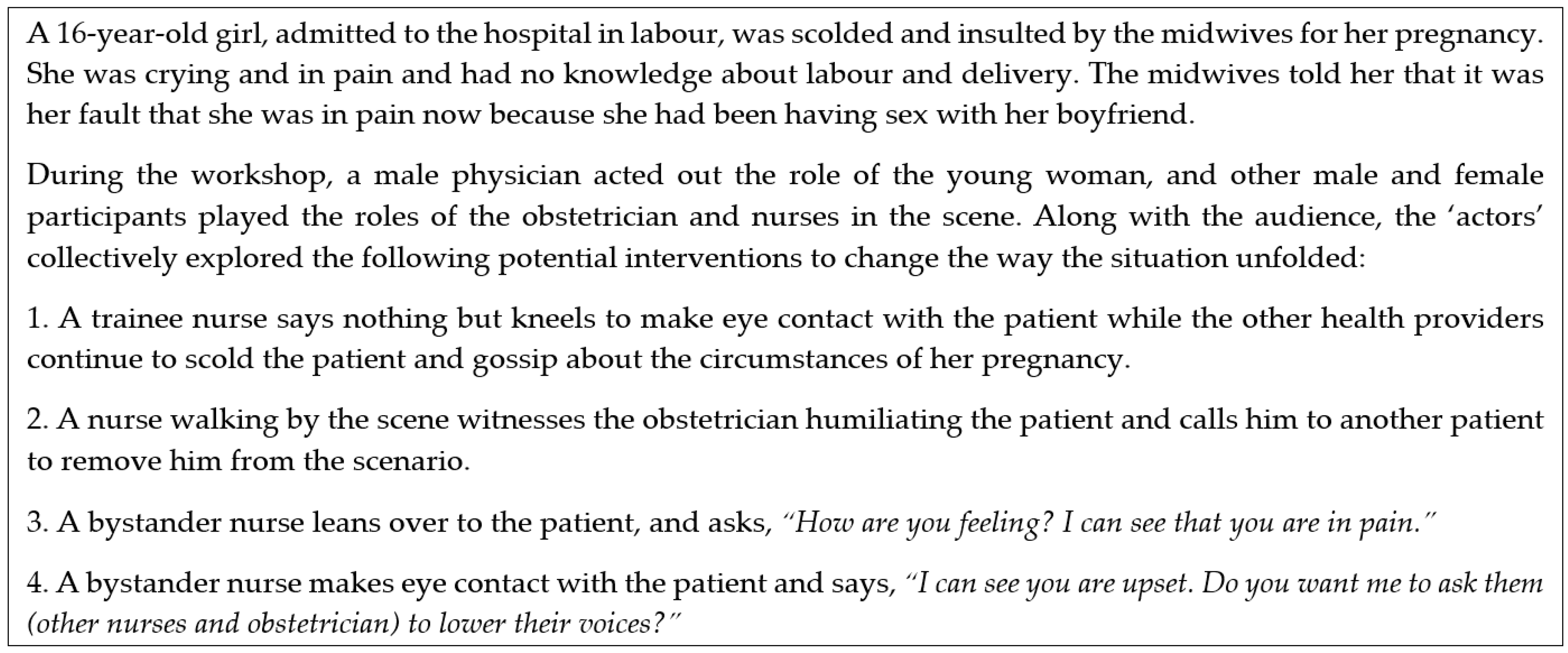

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Swahnberg, K.; Schei, B.; Hilden, M.; Halmesmaki, E.; Sidenius, K.; Steingrimsdottir, T.; Wijma, B. Patients’ Experiences of Abuse in Health Care: A Nordic Study on Prevalence and Associated Factors in Gynecological Patients. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2007, 86, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swahnberg, K.; Thapar-Bjorkert, S.; Bertero, C. Nullified: Women‘s Perceptions of Being Abused in Health Care. J. Psychosom Obstet. Gynaecol. 2007, 28, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohren, M.A.; Vogel, J.P.; Hunter, E.C.; Lutsiv, O.; Makh, S.K.; Souza, J.P.; Aguiar, C.; Saraiva Coneglian, F.; Diniz, A.L.A.; Tunçalp, Ö.; et al. The Mistreatment of Women During Childbirth in Health Facilities Globally: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowser, D.; Hill, K. Exploring Evidence for Disrespect and Abuse in Facility-Based Childbirth: Report of a Landscape Analysis; Harvard School of Public Health & University Research Co., LLC: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Savage, V.; Castro, A. Measuring Mistreatment of Women During Childbirth: A Review of Terminology and Methodological Approaches. Reprod. Health 2017, 14, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, M.; Santos, M.J.; Ruiz-Berdun, D.; Rojas, G.L.; Skoko, E.; Gillen, P.; Clausen, J.A. Moving Beyond Disrespect and Abuse: Addressing the Structural Dimensions of Obstetric Violence. Reprod. Health Matters 2016, 24, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vacaflor, C.H. Obstetric Violence: A New Framework for Identifying Challenges to Maternal Healthcare in Argentina. Reprod. Health Matters 2016, 24, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Tello, F. Invisible Wounds: Obstetric Violence in the United States. Reprod. Health Matters 2016, 24, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jewkes, R.; Abrahams, N.; Mvo, Z. Why Do Nurses Abuse Patients? Reflections from South African Obstetric Services. Soc. Sci. Med. 1998, 47, 1781–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Oliveira, A.F.; Diniz, S.G.; Schraiber, L.B. Violence Against Women in Health-Care Institutions: An Emerging Problem. J. Lancet 2002, 359, 1681–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, L.-M.; Schoombee, C. The Other Side of Caring: Abuse in a South African Maternity Ward. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2010, 28, 84–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, N.; Beebe, M.; Chase, R.P.; Doumbia, S.; Winch, P.J. Nègènègèn: Sweet Talk, Disrespect, and Abuse Among Rural Auxiliary Midwives in Mali. Midwifery 2015, 31, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, S.; McCourt, C.; Rayment, J.; Parmar, D. Review Article: Disrespectful Intrapartum Care During Facility-Based Delivery in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Qualitative Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis of Women‘s Perceptions and Experiences. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 169, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S Rominski, M.P.H. Ghanaian Midwifery Students‘ Perceptions and Experiences of Disrespect and Abuse During Childbirth. Lancet Glob. Health 2015, 3, S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, A.; Savage, V. Obstetric Violence as Reproductive Governance in the Dominican Republic. Med. Anthropol. 2018, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.; Lalonde, A. Reproductive Health: The Global Epidemic of Abuse and Disrespect During Childbirth: History, Evidence, Interventions, and FIGO‘s Mother−Baby Friendly Birthing Facilities Initiative. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2015, 131, S49–S52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, K. The Alleviation of Suffering–The Idea of Caring. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 1992, 6, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindholm, L.; Eriksson, K. To Understand and Alleviate Suffering in a Caring Culture. J. Adv. Nurs. 1993, 18, 1354–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. The Prevention and Elimination of Disrespect and Abuse During Facility-Based Childbirth. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/134588/1/WHO_RHR_14.23_eng.pdf?ua=1&ua=1 (accessed on 4 March 2019).

- World Ribbon Alliance. Respectful Maternity Care: The Universal Rights of Childbearing Women. Available online: https://www.whiteribbonalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Final_RMC_Charter.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2019).

- Perera, D.; Lund, R.; Swahnberg, K.; Schei, B.; Infanti, J.J.; Darj, E.; Lukasse, M.; Bjørngaard, J.H.; Joshi, S.K.; Rishal, P.; et al. ‘When Helpers Hurt’: Women’s and Midwives’ Stories of Obstetric Violence in State Health Institutions, Colombo District, Sri Lanka. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbikowski, A.; Zeiler, K.; Swahnberg, K. Forum Play as a Method for Learning Ethical Practice: A Qualitative Study Among Swedish Health-Care Staff. Clin. Ethics 2016, 11, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüggemann, A.J.; Persson, A. Using Forum Play to Prevent Abuse in Health Care Organizations: A Qualitative Study Exploring Potentials and Limitations for Learning. Educ. Health (Abingdon) 2016, 29, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Österlind, E. Forum Play: A Swedish Mixture for Consciousness and Change. In Key Concepts in Theatre/Drama Education; Schonmann, S., Ed.; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 247–251. ISBN 978-94-6091-332-7. [Google Scholar]

- Josephson, A. Forum Play. Available online: https://lt.ltag.bibl.liu.se/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsswe&AN=edsswe.oai.DiVA.org.liu.76105&site=eds-live (accessed on 4 March 2019).

- Byréus, K. Du Har Huvudrollen i Ditt Liv: Om Forumspel som Pedagogisk Metod för Frigörelse och Förändring [You Play The Leading Part in Your Life: About Forumplay as a Learning Method for Liberation and Change]; Liber: Stockholm, Sweden, 2010; ISBN 978-914-709-976-4. [Google Scholar]

- Boal, A. The Rainbow of Desire: The Boal Method of Theatre and Therapy; Routledge: London, UK, 1995; ISBN 978-041-510-349-7. [Google Scholar]

- Boal, A. Theater of The Oppressed; Pluto: London, UK, 2000; ISBN 978-093-045-249-0. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of The Oppressed; The Seabury Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974; ISBN 978-014-025-403-7. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, K.H.; Gillespie, D. “We Become Brave by Doing Brave Acts”: Teaching Moral Courage through the Theater of The Oppressed. Lit Med. 1997, 16, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, S. From Boal to Jana Sanskriti: Practice and Principles; Routledge: Basingstoke, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-113-822-332-5. [Google Scholar]

- Brett-MacLean, P.; Yiu, V.; Farooq, A. Exploring Professionalism in Undergraduate Medical and Dental Education through Forum Theatre. J. Learn. Arts 2012, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, J. Exploring Empowerment Issues with Student Midwives using Forum Theatre. Br. J. Midwifery 2009, 17, 438–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, K.I. Using Theater of The Oppressed in Nursing Education: Rehearsing to be Change Agents. J. Learn. Arts 2012, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClimens, A.; Scott, R. Lights, Camera, Education! The Potentials of Forum Theatre in a Learning Disability Nursing Program. Nurse Educ. Today 2007, 27, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middlewick, Y.; Kettle, T.; Wilson, J. Curtains Up! Using Forum Theatre to Rehearse the Art of Communication in Healthcare Education. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2012, 12, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arveklev, S.H.; Berg, L.; Wigert, H.; Morrison-Helme, M.; Lepp, M. Learning About Conflict and Conflict Management Through Drama in Nursing Education. J. Nurs. Educ. 2018, 57, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbikowski, A. Counteracting Abuse in Health Care from a Staff Perspective: Ethical Aspects and Practical Implications. Ph.D. Thesis, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman, L.P.; Kujawski, S.A.; Mbuyita, S.; Kuwawenaruwa, A.; Kruk, M.E.; Ramsey, K.; Mbaruku, G. Eye of The Beholder? Observation Versus Self-Report in The Measurement of Disrespect and Abuse During Facility-Based Childbirth. Reprod. Health Matters 2018, 26, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swahnberg, K.; Wijma, B. Staff’s Perception of Abuse in Healthcare: A Swedish Qualitative Study. BMJ Open 2012, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swahnberg, K.; Wijma, B. Staff‘s Awareness of Abuse in Health Care Varies According to Context and Possibilities To Act. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2011, 32, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, G.; Reddy, B.; Iyer, A. Beyond Measurement: The Drivers of Disrespect and Abuse in Obstetric Care. Reprod. Health Matters 2018, 26, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Response Options | Baseline | Follow-up | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 50 | n = 30 | |||

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Sex | Female | 41(82.0) | 27(90.0) | |

| Male | 9(18.0) | 3(10.0) | ||

| 0.520 | ||||

| Age | 19–34 | 14(28.0) | 2(6.7) | |

| 35–50 | 30(60.0) | 21(70.0) | ||

| 51–62 | 6(12.0) | 7(23.3) | ||

| 0.049 | ||||

| Ethnicity | Singhalese | 47(94.0) | 29(96.7) | |

| Tamil | 1(2.0) | 0(0.0) | ||

| Moor or Muslim | 2(4.0) | 1(3.3) | ||

| Other | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | ||

| 0.728 | ||||

| Occupation | Physician | 20(40.0) | 5(16.7) | |

| Nurse | 30(60.0) | 25(83.3) | ||

| 0.045 | ||||

| Work experience (years) | 0–2 | 3(6.0) | 0(0.0) | |

| 3–12 | 25(50.0) | 10(34.5) | ||

| 13–22 | 16(32.0) | 13(44.8) | ||

| 23–33 | 6(12.0) | 6(20.7) | ||

| Missing | 1 | |||

| 0.215 |

| Variable | Response Options | Baseline | Follow-up | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 50 | n = 30 | |||

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

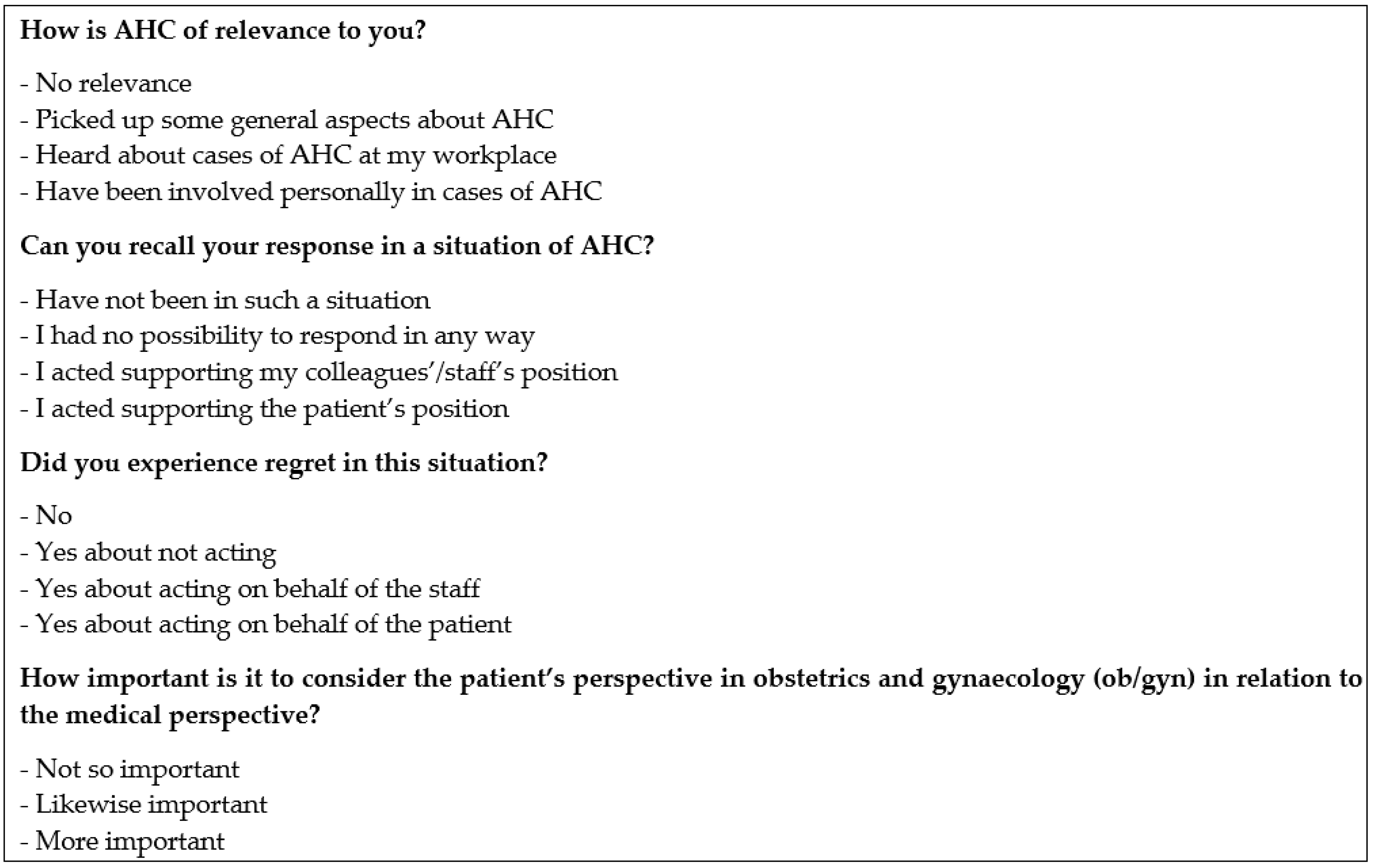

| How is AHC of relevance to you? | No relevance | 2(4.0) | 0(0.0) | |

| Picked up some general aspects about AHC | 24(48.0) | 7(23.3) | ||

| Heard about cases of AHC at my workplace | 15(30.0) | 10(33.3) | ||

| Have been involved personally in cases of AHC | 9(18.0) | 13(43.3) | ||

| 0.035 | ||||

| Can you recall your response in a situation of AHC? | Have not been in such a situation | 21(43.8) | 9(30.0) | |

| I had no possibility to respond in any way | 8(16.7) | 6(20.0) | ||

| I acted supporting my colleagues’/staff’s position | 2(4.2) | 1(3.3) | ||

| I acted supporting the patient’s position | 17(35.4) | 13(43.3) | ||

| Missing | 2 | 1 | ||

| 0.565 | ||||

| Did you experience regret in this situation? | No | 12(40.0) | 13(43.3) | |

| Yes about not acting | 8(26.7) | 5(16.7) | ||

| Yes about acting on behalf of the staff | 1(3.3) | 1(3.3) | ||

| Yes about acting on behalf of the patient | 1(3.3) | 1(3.3) | ||

| Missing 1 | 28(56.0) | 10(33.5) | ||

| 0.964 | ||||

| How important is it to consider the patient’s perspective in obstetrics and gynaecology (ob/gyn) in relation to the medical perspective? | Not so important | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | |

| Likewise important | 17(37.8) | 16(53.3) | ||

| More important | 28(62.2) | 13(43.3) | ||

| Missing | 5 | 1 | ||

| 0.160 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Swahnberg, K.; Zbikowski, A.; Wijewardene, K.; Josephson, A.; Khadka, P.; Jeyakumaran, D.; Mambulage, U.; Infanti, J.J. Can Forum Play Contribute to Counteracting Abuse in Health Care? A Pilot Intervention Study in Sri Lanka. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1616. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16091616

Swahnberg K, Zbikowski A, Wijewardene K, Josephson A, Khadka P, Jeyakumaran D, Mambulage U, Infanti JJ. Can Forum Play Contribute to Counteracting Abuse in Health Care? A Pilot Intervention Study in Sri Lanka. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(9):1616. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16091616

Chicago/Turabian StyleSwahnberg, Katarina, Anke Zbikowski, Kumudu Wijewardene, Agneta Josephson, Prembarsha Khadka, Dinesh Jeyakumaran, Udari Mambulage, and Jennifer J. Infanti. 2019. "Can Forum Play Contribute to Counteracting Abuse in Health Care? A Pilot Intervention Study in Sri Lanka" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 9: 1616. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16091616

APA StyleSwahnberg, K., Zbikowski, A., Wijewardene, K., Josephson, A., Khadka, P., Jeyakumaran, D., Mambulage, U., & Infanti, J. J. (2019). Can Forum Play Contribute to Counteracting Abuse in Health Care? A Pilot Intervention Study in Sri Lanka. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(9), 1616. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16091616