Improving the Living, Learning, and Thriving of Young Black Men: A Conceptual Framework for Reflection and Projection

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

Mental Health, Masculinities, and Social Support for Young Black Men

3. The YBMen Project

3.1. Description of the YBMen Project Intervention

3.2. The YBMen Project: Intervention Goals and Objectives

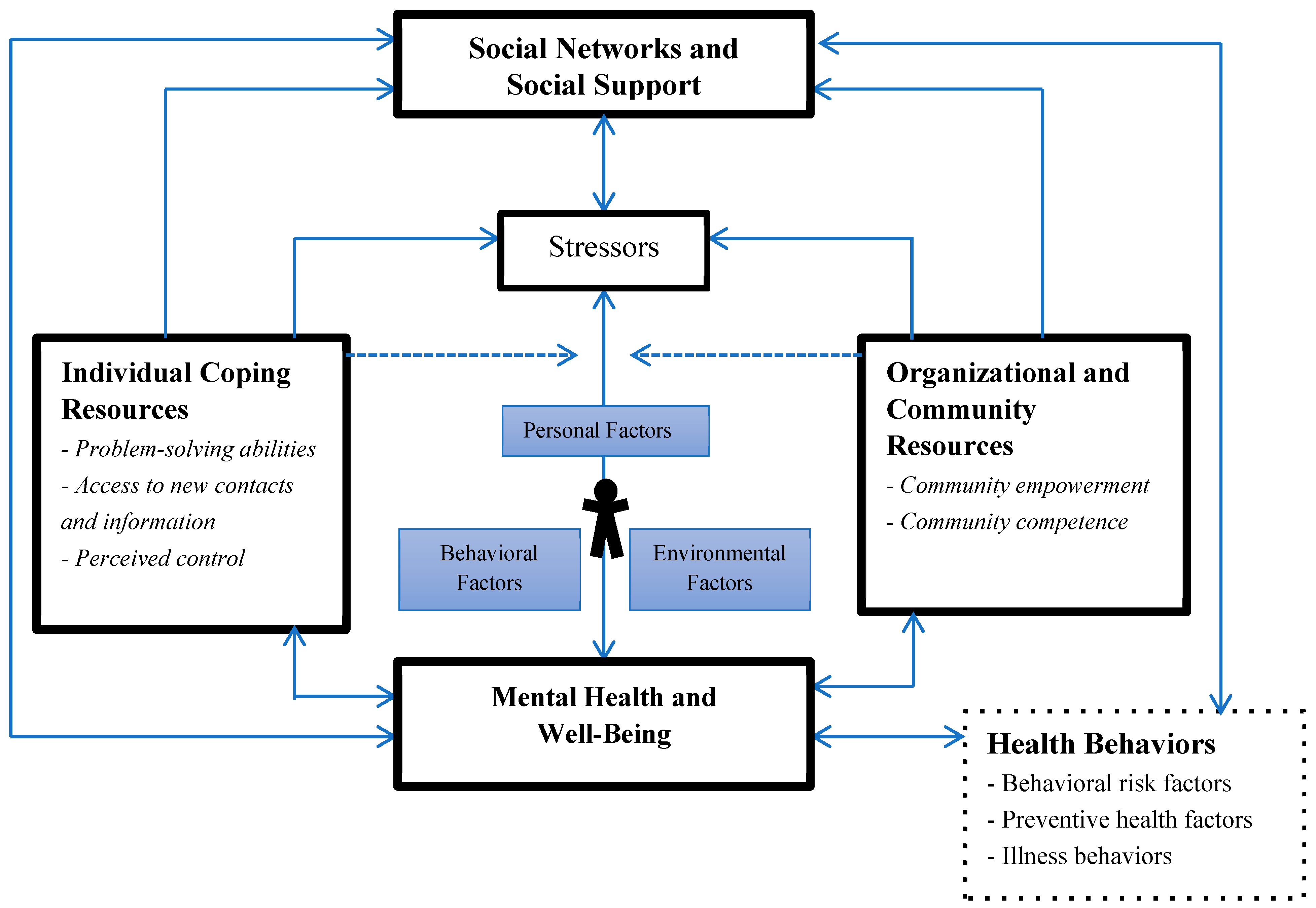

3.3. The YBMen Project Conceptual Framework

4. Reflections: Looking Back at What We Have Done

4.1. The Importance of Including Multiple Measures to Understand Black Men and Mental Health

4.2. The Importance of Social Media and Online Social Support in Programs for Black Men

4.3. The Importance of Prioritizing Behavioral Health Interventions for Young Black Men

4.4. The Importance of Evaluation for Interventions Aimed at Boys and Men of Color

5. Projections: Looking Ahead to the Future

6. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Benson, J.E. Young adult identities and their pathways: A developmental life course model. Dev. Psychol. 2011, 47, 1646–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erikson, E.H. Identity: Youth and Crisis; Norton & Co.: Oxford, UK, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Rowling, L. Adolescence and Emerging Adulthood (12–17 years and 18–24 years). In Mental Health Promotion. A Lifespan Approach; Cattan, M., Tilford, S., Eds.; The McGrawHill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, K.D.; Taylor, R.J.; Watkins, D.C.; Chatters, L. Correlates of psychological distress and major depressive disorder among African American men. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2011, 21, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lease, S.H.; Shuman, W.A.; Gage, A.N. Incorporating traditional masculinity ideology into health promotion models: Differences for African American/Black and White men. Psych. Men Masc. 2019, 20, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R. The health of men: Structured inequalities and opportunities. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 724–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watkins, D.C. Depression over the adult life course for African American men: Toward a framework for research and practice. Am. J. Men’s Health 2012, 6, 194–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, D.C.; Hudson, D.L.; Caldwell, C.H.; Siefert, K.; Jackson, J.S. Discrimination, mastery, and depressive symptoms among African American men. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2011, 21, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paxton, K.C.; Robinson, W.L.; Shah, S.; Schoeny, M.E. Psychological distress for African- American adolescent males: Exposure to community violence and social support as factors. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2004, 34, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers, S.L.; Bonham, V.; Neighbors, H.W.; Amell, J.W. Effects of racial discrimination and health behaviors on mental and physical health of middle-class African American men. Health Ed. Behav. 2009, 36, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierre, M.R.; Mahalik, J.R.; Woodland, M. The effects of racism, African self-consciousness and psychological functioning on Black masculinity: A historical and social adaptation framework. J. Afr. Am. Men 2001, 6, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaines, J.S. Social correlates of psychological distress among adult African American males. J. Black Stud. 2007, 37, 827–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunson, R.K. Police don’t like Black people: African-American young men’s accumulated police experiences. Criminol. Public Policy 2007, 6, 71–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre, M.R.; Mahalik, J.R. Examining African self-consciousness and Black racial identity as predictors Black men’s psychological well being. Cult. Divers Ethn. Minor Psychol. 2005, 11, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wester, S.R.; Vogel, D.L.; Wei, M.; McLain, R. African-American men, gender role conflict, and psychological distress: The role of racial identity. J. Couns. Dev. 2006, 84, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, D.C.; Green, B.L.; Rivers, B.M.; Rowell, K.L. Depression in Black men: Implications for future research. J. Men’s Health Gender 2006, 3, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, D.C.; Walker, R.L.; Griffith, D.M. A meta-study of Black male mental health and well-being. J. Black Psychol. 2010, 36, 303–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, D.M.; Gunter, K.E.; Watkins, D.C. Measuring masculinity in research on men of color: Findings and future directions. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, S187–S194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parham, T.A.; White, J.L.; Ajamu, A. The Psychology of Blacks: An African Centered Perspective; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Y.J.; Ringo Ho, M.-H.; Wang, S.-Y.; Miller, I.S.K. Meta-Analyses of the relationship between conformity to masculine norms and mental health-related outcomes. J. Couns. Psychol. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, W.P. Taking it like a man: Masculine role norms as moderators of the racial discrimination-depressive symptoms association among African American men. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, S232–S241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, A.A. Bad Boys: Public Schools in the Making of Black Masculinity (Law, Meaning, and Violence); University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, D.C.; Green, B.L.; Goodson, P.; Guidry, J.; Stanley, C.A. Using focus groups to explore the stressful life events of Black college men. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2007, 48, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majors, R.; Billson, J.M. Cool Pose: The Dilemmas of Black Manhood in America; Lexington Books: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, Y.A. Site of resilience: A reconceptualization of resiliency and resilience in street life–oriented Black men. J. Black Psychol. 2011, 37, 426–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, D.C.; Neighbors, H.W. An initial exploration of what ‘mental health’ means to young Black men. J. Men’s Health Gender 2007, 4, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalik, J.R.; Locke, B.D.; Ludlow, L.H.; Demer, M.A.; Scott, R.P.; Gottfried, M.; Freitas, G. Development of the conformity to masculine norms inventory. Psych. Men Masculinity 2003, 4, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association, APA Working Group on Health Disparities in Boys and Men. Health Disparities in Racial/Ethnic and Sexual Minority Boys and Men. 2018. Available online: http://www.apa.org/pi/ health-disparities/resources/race-sexuality-men.aspx (accessed on 12 March 2019).

- Englar-Carlson, M.; Kiselica, M.S. Affirming the strengths in men: A positive masculinity approach to assisting male clients. J. Couns. Dev. 2013, 91, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association, Boys and Men Guidelines Group. APA Guidelines for Psychological Practice with Boys and Men. 2018. Available online: http://www.apa.org/about/policy/psychological-practice-boys-men-guidelines.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2019).

- Watkins, D.C.; Smith, L.C.; Kerber, K.; Kuebler, J.; Himle, J. E-mail as a depression self-management tool: A needs assessment to determine patients’ interests and preferences. J. Telemed. Telecare 2011, 17, 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, D.C.; Jefferson, S.O. Recommendations for the use of online social support for African American men. Psychol. Serv. 2013, 10, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, D.C.; Allen, J.O.; Goodwill, J.R.; Noel, B. Strengths and weaknesses of the Young Black Men, Masculinities, and Mental Health (YBMen) Facebook Project. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2017, 87, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, D.M. An intersectional approach to men’s health. J. Men’s Health 2012, 9, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, K.D.; Chae, D.H. Social support, negative interaction, and lifetime major depressive disorder among African Americans and Caribbean Blacks. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2011, 47, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.A.; Neighbors, H.W.; Griffith, D.M. The experience of symptoms of depression in men vs. women: Analysis of the national comorbidity survey replication. JAMA Psychiatry 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, J.S. Influence of race and symptom expression on clinicians’ depressive disorder identification in African American men. J. Soc. Soc. Work Res. 2012, 3, 162–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, G.R.; Silverstein, L.B. The dark side of masculinity. In A New Psychology of Men; Levant, R.F., Pollack, W.S., Eds.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 280–305. [Google Scholar]

- Mahalik, J.R.; Talmadge, W.T.; Locke, B.D.; Scott, R.J. Using the conformity to masculine norms inventory to work with men in a clinical setting. J. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 61, 661–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addis, M.; Mahalik, J. Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help seeking. Am. Psychol. 2003, 58, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochlen, A.B.; Hoyer, W.D. Marketing mental health to men. J. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 61, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtenay, W.H. Key determinants of the health and well-being of men and boys. Int. J. Men’s Health 2003, 2, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.H.; Wu, S.Z.; Liu, Y.Y. Association between social support and health outcomes: A meta-analysis. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2003, 19, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.J.; Ozkaya, E.; LaRose, R. How does online social networking enhance life satisfaction? The relationships among online support interaction, affect, perceived social support, sense of community, and life satisfaction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 30, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, M.A.; Goldstein, B.A. Self-help on-line: An outcome evaluation of breast cancer bulletin boards. J. Health Psychol. 2005, 10, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, N.B.; Vitak, J.; Gray, R.; Lampe, C. Cultivating social resources on social network sites: Facebook relationship maintenance behaviors and their role in social capital processes. J. Comput. Med. Commun. 2014, 19, 855–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.; Dorman, S.M. Receiving social support online: Implications for health education. Health Educ. Res. 2001, 16, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kernsmith, P.; Kernsmith, R. A safe place for predators: Online treatment of recovering sex offenders. J. Technol. Hum. Serv. 2008, 26, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, C.; Cotton, S.R. The relationship between Internet activities and depressive symptoms in a sample of college freshmen. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2003, 6, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaRose, R.; Eastin, M.S.; Gregg, J. Reformulating the internet paradox: Social cognitive explanations of Internet use and depression. J. Online Behav. 2001, 1. Available online: http://www.behavior.net/JOB/v1n2/paradox.html (accessed on 12 March 2019).

- Pinnock, C.B.; Jones, C. Meeting the information needs of Australian men with prostate cancer by way of the Internet. Urology 2003, 61, 1198–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulveen, R.; Hepworth, J. An interpretive phenomenological analysis of participation in pro-anorexia Internet site and its relationship with disordered eating. J. Health Psychol. 2006, 11, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, T.L.; Goldsmith, D. Social support, social networks, and health. In Handbook of Health Communication; Thompson, T.L., Dorsey, A.M., Miller, K.I., Parrott, R., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 263–284. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, T.; Yeh, C.J. Using online groups to provide support to Asian American men: Racial, cultural, gender, and treatment issues. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2003, 34, 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwill, J.R.; Watkins, D.C.; Johnson, N.C.; Allen, J.O. An exploratory study of coping among Black college men. Am. J. Orthopsychol. 2018, 88, 538–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. The evolution of social cognitive theory. In Great Minds of Management: The Process of Theory Development, 2nd ed.; Smith, K.G., Hitt, M.A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 460–484. [Google Scholar]

- Heaney, C.A.; Israel, B.A. Social networks and social support. In Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice; Glanz, K., Rimer, B.K., Viswanath, K., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 189–210. [Google Scholar]

- Baranowski, T.; Perry, C.L.; Parcel, G.S. How individuals, environments, and health behavior interact. In Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice, 2nd ed.; Glanz, K., Lewis, F.M., Rimer, B.K., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, N.B.; Vitak, J. Social Network Site Affordances and their Relationship to Social Capital Processes. In The Handbook of the Psychology of Communication Technology; Sundar, S., Ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 205–227. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, N.B.; Steinfield, C.; Lampe, C. The benefits of Facebook “friends:” Social capital and college students use of online social network sites. J. Comput. Med. Commun 2007, 12, 1143–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitak, J.; Ellison, N.B. ‘There’s a network out there you might as well tap’: Exploring the benefits of and barriers to exchanging informational and support-based resources on Facebook. New Media Soc. 2013, 15, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klienman, A. Facebook Adds a New Feature for Suicide Prevention. The Huffington Post. 25 February 2015. Available online: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/02/25/facebook-suicide-prevention_n_6754106.html (accessed on 12 March 2019).

- McKeown, M.; Robertson, S.; Habte-Mariam, Z.; Stowell Smith, M. Masculinity and emasculation for black men in modern mental health care. Ethn. Inequal. Health Soc. Care 2008, 1, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, D.C.; Griffith, D.M. Practical solutions to addressing men’s health disparities. Int. J. Men’s Health 2013, 12, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, N.H.; Dillaway, H.E.; Yarandi, H.N.; Jones, L.M.; Wilson, F.L. An examination of eating behaviors, physical activity, and obesity in African American adolescents: Gender, socioeconomic status, and residential status differences. J. Pediatric Health Care 2015, 29, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, N.H.; Davis, J.E.; Yarandi, H.N. Sociocultural Influences on Weight-Related Behaviors in African American Adolescents. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, R.; Groce, J.; Thomas, N. Changing direction: Rites of passage programs for African American older men. J. Afr. Am. Stud. 2003, 7, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuvekas, S.H.; Taliaferro, G.S. Pathways to Access: Health Insurance, the Health Care Delivery System, and Racial/Ethnic Disparities, 1996–1999. Health Affairs 2003, 22, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Social Determinants of Health. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/social_determinants/en/ (accessed on 10 March 2019).

| SCT Concept | Definition | Application to the YBMen Project |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral capacity | Knowledge and skills to influence behavior | Educate Ps on individual and collective definitions of mental health, manhood, and social support and empowering their role as change agents. |

| Expectations | Anticipatory outcomes of a behavior; Model positive outcomes of healthful behavior | Encourage Ps to describe positive and negative outcomes of their previous behaviors. |

| Observational learning | Behavioral acquisition that occurs by watching the actions and outcomes of others’ behavior; Include credible role models of the targeted behavior | Share Ps individual and collective experiences; Identify credible role models to emulate that help portray the experiences of Black men in society. |

| Reinforcement | Responses to a person’s behavior that increase or decrease the likelihood of reoccurrence; Promote self-initiated rewards and incentives | Offer praise to and between Ps; Encourage self-reward; Decrease possibility of negative responses that deter positive changes. |

| Reciprocal determinism | The dynamic interaction of the person, the behavior, and the environment in which the behavior is performed | Involve Ps and others in program adaptation; Work with Ps to consider multiple avenues to behavioral change including environmental, skill-based, and personal change. |

| Self-efficacy | The person’s confidence in performing a particular behavior; Approach behavioral change in small steps to ensure success | Work with Ps to acknowledge strengths; Use persuasion and encouragement; Behavior change occurs via small, achieveable milestones that Ps can master. |

| Concepts | Definitions | Application to the YBMen Project |

|---|---|---|

| Structural characteristics of social networks | ||

| Reciprocity | Extent to which resources and support are both given and received in a relationship | Ps receive information from the program, but are also asked to share information with members of their group. |

| Intensity of strength | Extent to which social relationships offer emotional closeness | Some Ps know one another prior to the start of the group while others strengthen relationships while in the group. |

| Complexity | Extent to which social relationships serve many functions | Given the nature of the topics covered in the groups, the needs and expectations of Ps may expand |

| Formality | Extent to which social relationships exist in the context of organizational or institutional roles | Many Ps are students and/or members of social groups. Many of their group exchanges are in this context. |

| Density | Extent to which network members know and interact with each other | Some Ps see and interact with one another outside of YBMen; others restrict their contact to what occurs within the group. |

| Homogeneity | Extent to which network members are demographically similar | Many Ps are connected via race and gender and associated experiences. Other identifying characteristics emerge in the YBMen group. |

| Geographic dispersion | Extent to which network members live in close proximity to focal person | Due to the focus on community, facilitated by on online community, the idea of proximity is less emphasized. |

| Directionality | Extent to which members of the dyad share equal power and influence | Ps are on an ‘even’ playing field. This may influence their interaction with the YBMen group moderator, who remains anonymous throughout the program. |

| Functions of social networks | ||

| Social Capital | Resources characterized by norms of reciprocity and social trust | Built by Ps in YBMen groups; particularly helpful when Ps vary by age, economic position, focus of study or work, identity, geographic area, etc. |

| Social Influence | Process by which thoughts and actions are changed by the actions of others | YBMen is based on social influence that helps Ps make informed decisions about how their mental health, manhood, and support are integrated. |

| Social undermining | Process by which others express negative affect or criticism or hinder one’s attainment of goals | Ps may be exposed to this based on group dynamics and individual contributions of Ps. Rapport-building early influences this concept. |

| Companionship | Sharing leisure or other activities with network | Regarded as a possible outcome of the YBMen program by Ps. |

| Social Support | Aid and assistance exchanged through social relationships and interpersonal transactions | A core aim of YBMen. Ps often come to the program interested in social support, and leave with a renewed appreciation for quality relationships. |

| Types of social support | ||

| Emotional support | Expressions of empathy, love, trust, and caring | Evident in group once Ps build rapport and normalize men’s emotions. |

| Instrumental support | Tangible aid and services | Not the focus of the group, but may occur once networks are built and connections are made. |

| Informational support | Advice, suggestions, and information | Evident in group once Ps build rapport and realize they have contributions to make. |

| Appraisal support | Information that is useful for self-evaluation | Ongoing introspection among Ps in the YBMen groups. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Watkins, D.C. Improving the Living, Learning, and Thriving of Young Black Men: A Conceptual Framework for Reflection and Projection. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1331. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16081331

Watkins DC. Improving the Living, Learning, and Thriving of Young Black Men: A Conceptual Framework for Reflection and Projection. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(8):1331. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16081331

Chicago/Turabian StyleWatkins, Daphne C. 2019. "Improving the Living, Learning, and Thriving of Young Black Men: A Conceptual Framework for Reflection and Projection" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 8: 1331. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16081331

APA StyleWatkins, D. C. (2019). Improving the Living, Learning, and Thriving of Young Black Men: A Conceptual Framework for Reflection and Projection. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(8), 1331. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16081331