The Relationship between Power Type, Work Engagement, and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors

Abstract

1. Introduction

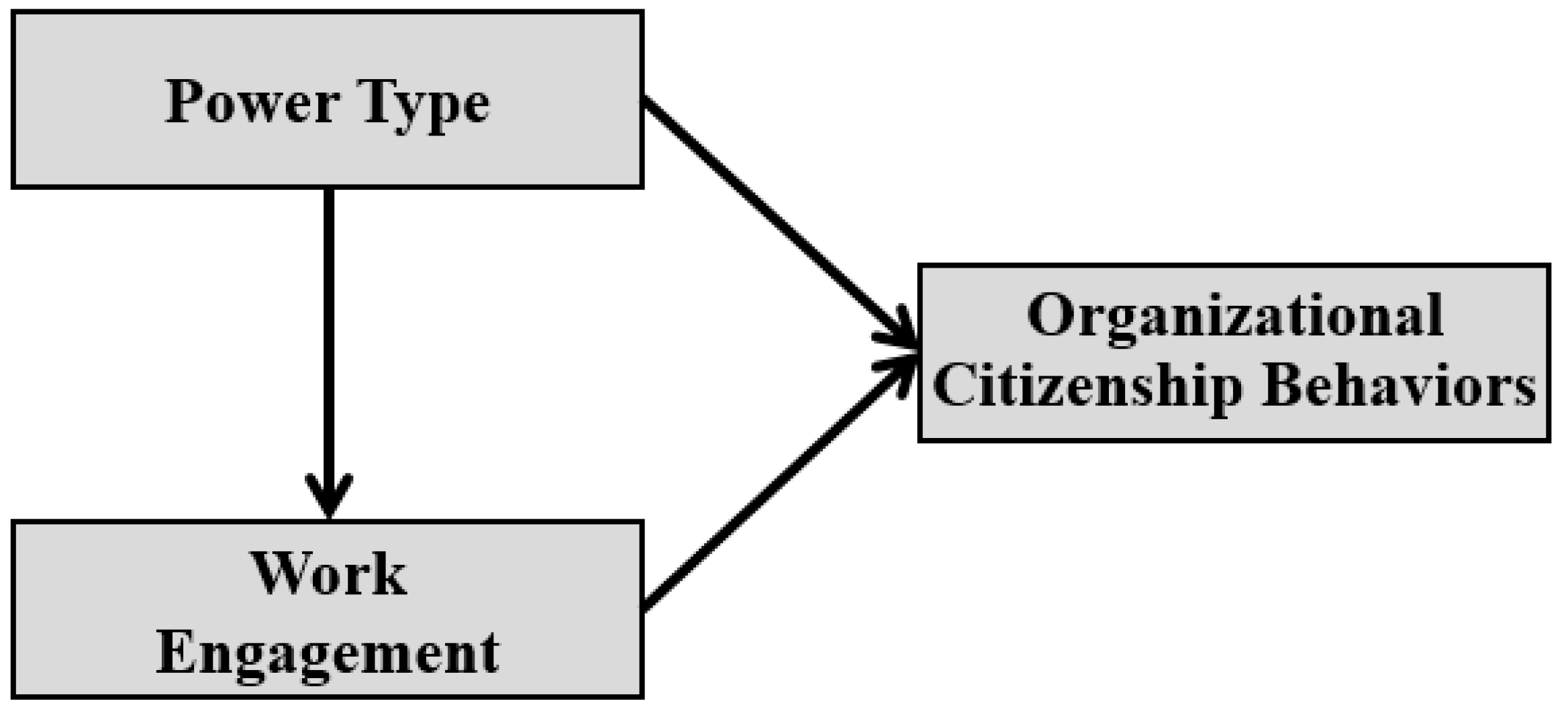

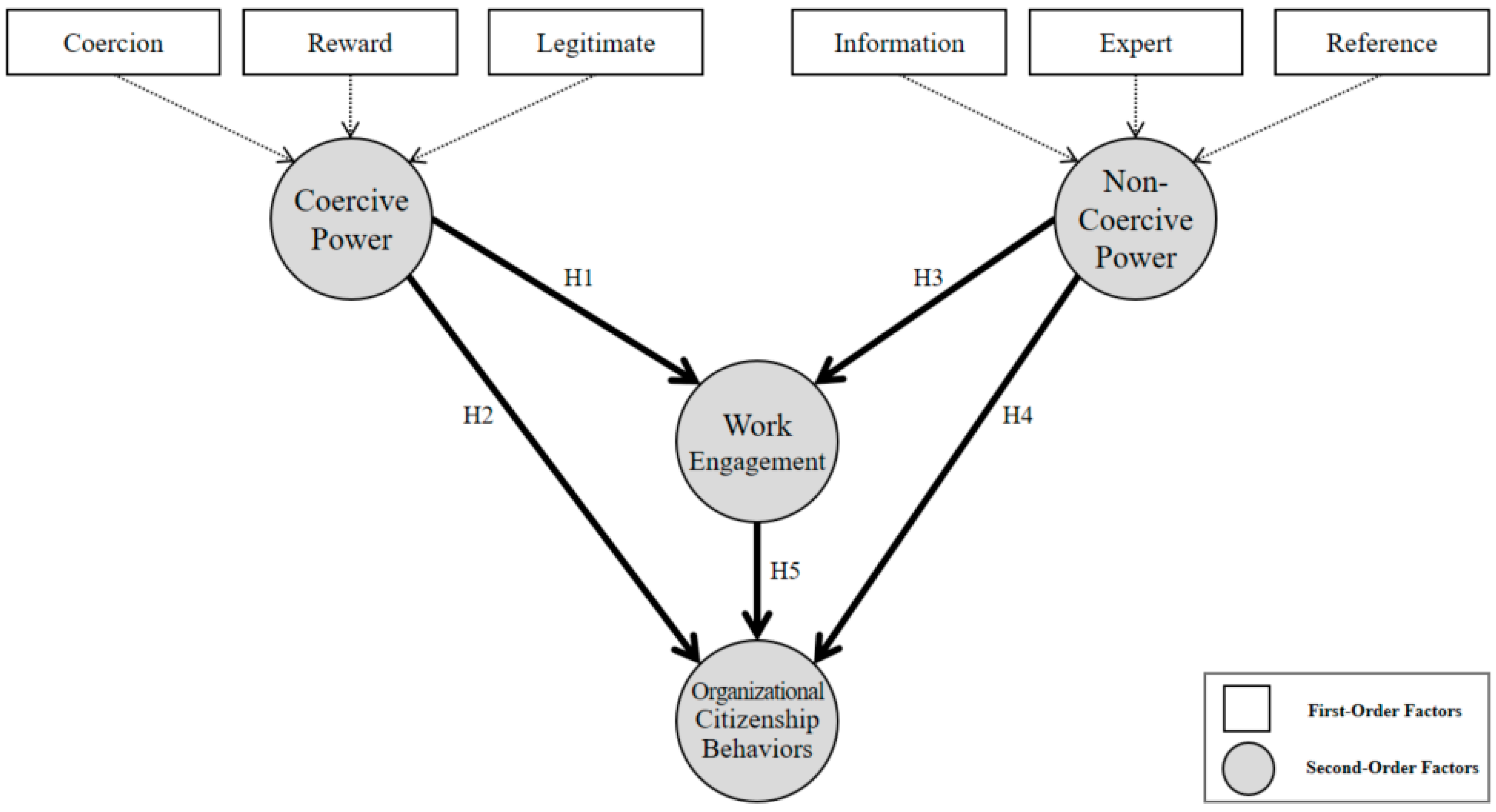

2. Theoretical Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Hypothesis Development

2.2. Sample and Data Collection

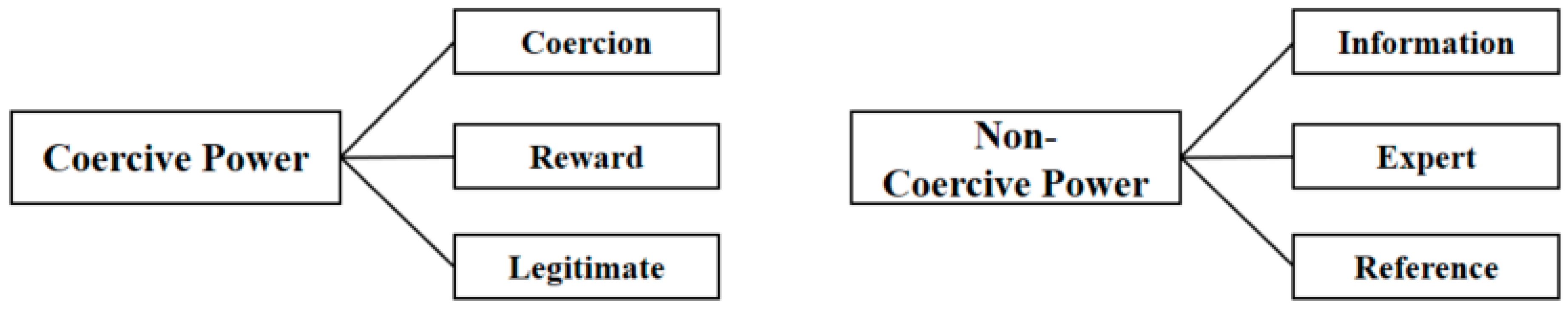

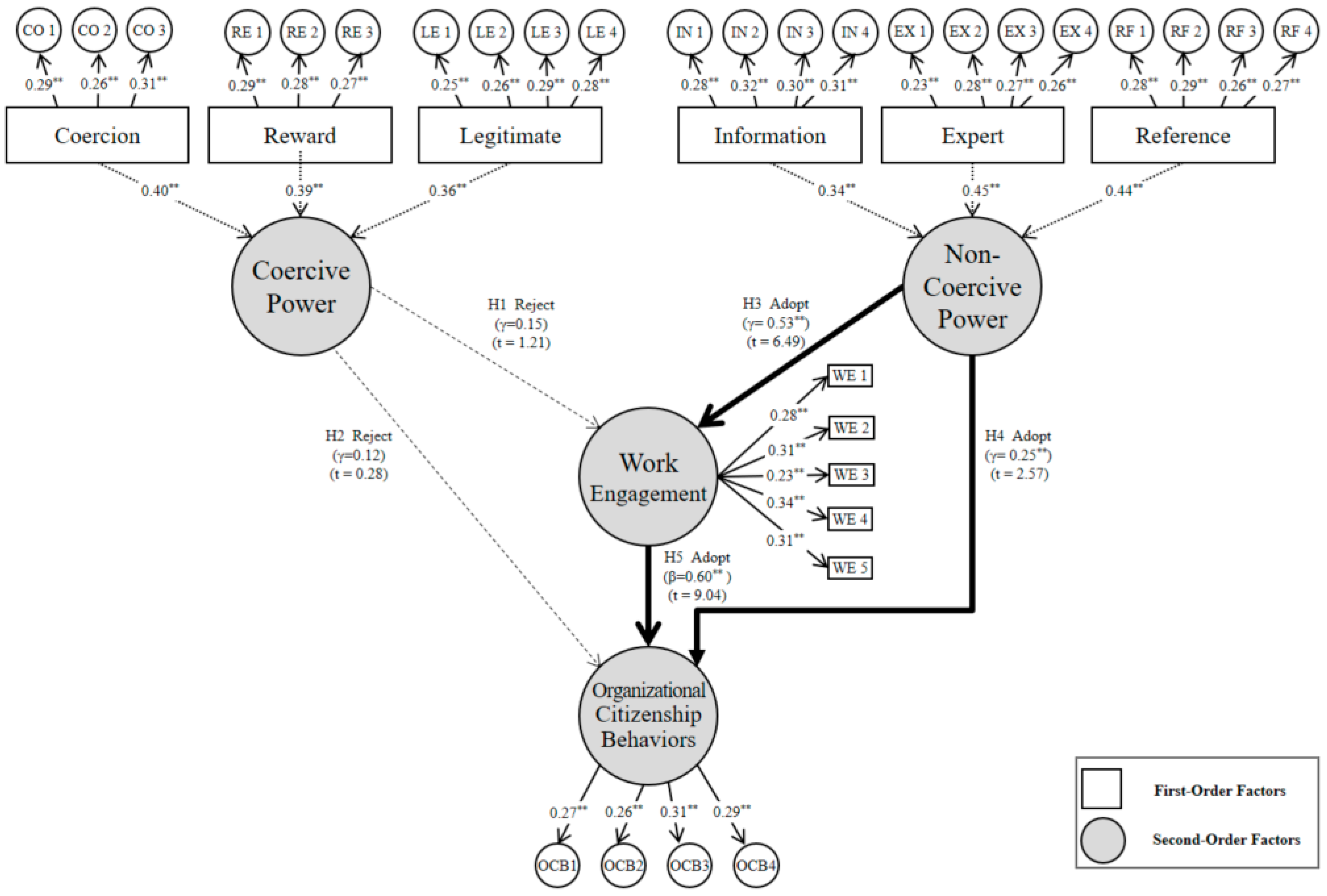

2.3. Measurement Model

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Emerson, R.M. Power-Dependence Relations. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1962, 27, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.O.; Chang, H.S.; Jung, D.H. How Do Power Type and Partnership Quality Affect Supply Chain Management Performance? Sustainability 2017, 9, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S.D.; Nevin, J.R. Power in a Channel of Distribution: Sources and Consequences. J. Mark. Res. 1974, 11, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W.A. To be fully there: Psychological Presence at Work. Hum. Relat. 1992, 45, 321–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, R.S.; Baysinger, M.; Brummel, B.J.; LeBreton, J.M. The relative Importance of Employee Engagement, other Job Attitudes, and Trait affect as Predictors of Job Performance. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 42, 295–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, B.L.; Lepine, J.A.; Crawford, E.R. Job Engagement: Antecedents and Effects on Job Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, J.K.; Schmidt, F.L.; Hayes, T.L. Business-Unit-Level Relationship between Employee Satisfaction, Employee Engagement, and Business Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallup Consulting. Employee Engagement: What’s your Engagement Ratio? Gallup Inc.: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.A.; Organ, D.W.; Near, J.P. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Its Nature and Antecedents. J. Appl. Psychol. 1983, 68, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Paine, J.B.; Bachrach, D.G. Organizational Citizenship Behaviors: A Critical Review of the Theoretical and Empirical Literature and Suggestions for Future Research. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 513–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausman, A.; Johnston, W.J. The Impact of Coercive and Non-Coercive Forms of Influence on Trust, Commitment, and Compliance in Supply Chains. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2010, 39, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, W.C.; Maloni, M. The Influence of Power driven Buyer/Seller Relationships on Supply Chain Satisfaction. J. Oper. Manag. 2005, 23, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaseshan, B.; Yip, L.S.; Pae, J.H. Power, Satisfaction, and Relationship Commitment in Chinese Store Tenant Relationship and Their Impact on Performance. J. Retail. 2006, 82, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, H. Software Piracy on the Internet: A Threat to Your Security; Business Software Alliance: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Maloni, M.; Benton, W.C. Power influences in the Supply Chain. J. Bus. Logist. 2000, 21, 49–74. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.R.; Lusch, R.F.; Nicholson, C.Y. Power and Relationship Commitment: Their Impact on Marketing Channel Member Performance. J. Retail. 1995, 71, 363–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Towards a Model of Work Engagement. Career Dev. Int. 2008, 13, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, M.S.; Garza, A.S.; Slaughter, J.E. Work Engagement: A Quantitative Review and Test of Its Relations with Task and Contextual Performance. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 89–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, I.Y.; Hur, W.M.; Jang, S.H. How and When Are Job Crafters Engaged at Work? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-Abal, Y.; Gómez-Salgado, J.; López-López, M.; Climent-Rodríguez, J. Organisational Justice, Burnout, and Engagement in University Students: A Comparison between Stressful Aspects of Labour and University Organisation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spagnoli, P.; Balducci, C.; Scafuri Kovalchuk, L.; Maiorano, F.; Buono, C. Are Engaged Workaholics protected against Job-related Negative Affect and Anxiety before Sleep? A Study of the Moderating Role of Gender. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job Burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job Demands, Job Resources, and Their Relationship with Burnout and Engagement: A Multi-Sample Study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W.A. Psychological Conditions of Personal Engagement and Disengagement at Work. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 692–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources Model: State of the Art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S.; Binnewies, C.; Mojza, E.J. Staying well and Engaged when Demands are high: The Role of Psychological Detachment. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 965–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. The Impact of Job Crafting on Job Demands, Job Resources, and Well-being. J. Occup. Health. Psychol. 2013, 18, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilies, R.; Nahrgang, J.D.; Morgeson, F.P. Leader-Member Exchange and Citizenship Behaviors: A Meta-Analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organ, D.W. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, J.W. An Essay on Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 1991, 4, 249–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, D.; Ting, L.; Palmer, A. A journey into the unknown; taking the fear out of structural equation modeling with AMOS for the first-time user. Mark. Rev. 2008, 8, 255–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References | Major Studies on Power |

|---|---|

| Hausman and Johnston [11] | Coercive Power/Non-Coercive Power |

| Maloni and Benton [15] | Mediated Power/Non-Mediated Power |

| Brown et al. [16] | Economic Power/Non-Economic Power |

| Construct | Items | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coercive Power | Coercion | If I disagree with a proposal of a superior, I will be in an undesirable situation. | Harter et al. [7] Hausman and Johnston [11] Benton and Maloni [12] Maloni and Benton [15] Brown et al. [16] |

| If I do not accept a request of a superior, I will be in an unfavorable situation. | |||

| If I do not accept a request of a superior, I receive a disadvantage. | |||

| Reward | If I do not accept a proposal of a superior, it will be difficult to receive an incentive. | ||

| If I do not accept a proposal of a superior, it will be difficult to receive economic benefits. | |||

| If I do not accept a proposal of a superior, it will be difficult to participate in a new project. | |||

| Legitimate | It is stated in the contract to accept proposals of a superior. | ||

| I have an obligation to accept the proposals of a superior. | |||

| The relationship is established such that I have to accept the proposals of a superior. | |||

| I have an obligation to accept the requests of a superior. | |||

| Non-Coercive Power | Information | The superior can provide me with useful information. | Ramaseshan et al. [13] Bakker & Demerouti [17] Christian, et al. [18] Spagnoli et al. [21] Maslach et al. [22] Schaufeli and Bakker [23] Bakker and Demerouti [25] Sonnentag et al. [26] |

| A work method of a superior can be helpful to me. | |||

| Because the decisions of a superior are rational, I reflect them in my work. | |||

| The superior provides me with reliable information. | |||

| Expert | The superior can provide me with helpful knowledge. | ||

| The superior can provide me with helpful experience. | |||

| The superior can provide me with helpful advice. | |||

| The superior can provide me with helpful decisions. | |||

| Reference | The value of a superior is a good example to follow. | ||

| The decision-making of a superior is a good example to follow. | |||

| The operation method of a superior is a good example to follow. | |||

| It is desirable to become like the superior. | |||

| Work Engagement | I am full of energy when I work. | Harter et al. [7] Shin et al. [19] Navarro-Abal et al. [20] Tims et al. [27] Ilies et al. [28] | |

| My work motivates me to work hard. | |||

| I am passionate when performing my job. | |||

| My work is highly meaningful and valuable. | |||

| I am highly involved when performing my job. | |||

| Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB) | I willingly spend time to help with the work-related problems of other employees. | Rich and Lepine [6] Kahn [24] Organ [29] Graham [30] | |

| I communicate effectively and work voluntarily. | |||

| Although it is not my duty, I strive to produce better job performance than what is stipulated. | |||

| I have loyalty and pride in the company. | |||

| Profiles of Respondents | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age of respondent | ||

| 30–40 | 89 | 48 |

| 40–50 | 66 | 36 |

| Over 50 | 29 | 16 |

| Gender of respondent | ||

| Male | 116 | 63 |

| Female | 68 | 37 |

| Job tenure of respondent | ||

| 1–5 | 69 | 37 |

| 5–10 | 62 | 34 |

| Over 10 | 53 | 29 |

| Title of respondent | ||

| Assistant manager | 62 | 34 |

| Manager | 57 | 31 |

| General manager | 42 | 23 |

| Executive director | 23 | 11 |

| Industry | ||

| Manufacturing/engineering | 59 | 32 |

| Services and utilities | 42 | 23 |

| Transportation and logistics | 45 | 24 |

| Retailing and wholesale | 38 | 21 |

| Number of employees | ||

| Less than 1000 | 52 | 28 |

| 1001–5000 | 79 | 43 |

| More than 5000 | 53 | 29 |

| Item | Coercion | OCB | Expert | Reference | Legitimate | Work Engagement | Information | Reward | Mean (S.D.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO1 | 0.776 | −0.101 | 0.110 | 0.156 | 0.257 | −0.065 | −0.023 | −0.252 | 4.30 (1.52) |

| CO2 | 0.828 | −0.126 | 0.102 | 0.032 | 0.279 | −0.031 | −0.120 | −0.274 | |

| CO3 | 0.861 | −0.068 | 0.051 | 0.097 | 0.123 | −0.079 | −0.034 | −0.242 | |

| RE1 | 0.402 | 0.003 | −0.087 | 0.082 | 0.193 | −0.020 | 0.065 | 0.809 | 3.88 (1.39) |

| RE2 | 0.392 | −0.001 | −0.073 | 0.084 | 0.154 | −0.076 | 0.127 | 0.832 | |

| RE3 | 0.219 | −0.006 | −0.003 | 0.000 | 0.134 | −0.072 | 0.081 | 0.859 | |

| LE1 | 0.214 | 0.074 | 0.052 | 0.071 | 0.835 | −0.012 | 0.069 | 0.031 | 3.80 (1.57) |

| LE2 | 0.223 | 0.157 | 0.125 | 0.122 | 0.873 | 0.049 | 0.064 | 0.060 | |

| LE3 | 0.262 | 0.042 | 0.119 | 0.069 | 0.863 | 0.132 | −0.088 | −0.056 | |

| LE4 | 0.158 | 0.132 | 0.042 | 0.086 | 0.901 | 0.056 | 0.051 | 0.005 | |

| IN1 | −0.164 | −0.062 | 0.470 | 0.139 | 0.023 | 0.226 | 0.566 | −0.220 | 4.72 (0.93) |

| IN2 | −0.017 | 0.126 | 0.258 | 0.271 | 0.072 | 0.102 | 0.747 | 0.126 | |

| IN3 | 0.247 | 0.242 | 0.098 | 0.451 | 0.087 | 0.119 | 0.534 | 0.385 | |

| IN4 | 0.204 | 0.012 | 0.287 | 0.381 | −0.010 | 0.249 | 0.604 | −0.032 | |

| EX1 | 0.075 | 0.074 | 0.890 | 0.065 | 0.124 | 0.031 | 0.105 | −0.053 | 5.11 (1.06) |

| EX2 | −0.002 | 0.119 | 0.915 | 0.175 | 0.109 | 0.098 | 0.089 | 0.035 | |

| EX3 | 0.037 | 0.123 | 0.901 | 0.176 | 0.034 | 0.062 | 0.163 | −0.005 | |

| EX4 | 0.006 | 0.217 | 0.837 | 0.181 | 0.065 | 0.111 | 0.123 | 0.038 | |

| RF1 | 0.130 | 0.163 | 0.189 | 0.827 | 0.067 | 0.085 | 0.160 | 0.019 | 4.47 (1.10) |

| RF2 | 0.098 | 0.228 | 0.102 | 0.835 | 0.170 | 0.151 | 0.189 | 0.005 | |

| RF3 | 0.027 | 0.142 | 0.199 | 0.871 | 0.061 | 0.191 | 0.056 | 0.088 | |

| RF4 | 0.086 | 0.016 | 0.148 | 0.830 | 0.094 | 0.145 | 0.219 | −0.106 | |

| WE1 | −0.078 | 0.384 | −0.041 | 0.289 | −0.034 | 0.594 | 0.414 | −0.235 | 4.74 (1.01) |

| WE2 | −0.062 | 0.402 | 0.041 | 0.198 | 0.069 | 0.643 | 0.196 | −0.162 | |

| WE3 | −0.089 | 0.152 | 0.162 | 0.098 | 0.134 | 0.859 | 0.104 | 0.110 | |

| WE4 | −0.125 | 0.465 | 0.134 | 0.282 | 0.039 | 0.697 | 0.009 | 0.091 | |

| WE5 | −0.087 | 0.447 | 0.121 | 0.247 | 0.042 | 0.776 | 0.237 | −0.076 | |

| OCB1 | −0.075 | 0.817 | 0.084 | 0.087 | 0.037 | 0.282 | −0.011 | 0.115 | 4.36 (1.40) |

| OCB2 | 0.016 | 0.873 | 0.192 | 0.124 | 0.152 | 0.077 | 0.148 | −0.055 | |

| OCB3 | −0.154 | 0.832 | 0.125 | 0.017 | 0.083 | 0.334 | −0.048 | 0.012 | |

| OCB4 | −0.004 | 0.814 | 0.128 | 0.247 | 0.160 | 0.148 | 0.080 | 0.025 |

| Measures | AVE | CR | Cronbach α |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coercion | 0.604 | 0.846 | 0.914 |

| Reward | 0.642 | 0.861 | 0.939 |

| Legitimate | 0.581 | 0.852 | 0.932 |

| Information | 0.622 | 0.826 | 0.795 |

| Expert | 0.561 | 0.768 | 0946 |

| Reference | 0.619 | 0.861 | 0.926 |

| Work Engagement | 0.553 | 0.838 | 0.916 |

| Organizational Citizenship Behaviors | 0.699 | 0.841 | 0.916 |

| Construct | Coercion | Reward | Legitimate | Information | Expert | Reference | Work Engagement | OCB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coercion | 0.777 | |||||||

| Reward | 0.690 ** | 0.801 | ||||||

| Legitimate | 0.427 ** | 0.374 ** | 0.762 | |||||

| Information | 0.099 | 0.139 | 0.195 ** | 0.789 | ||||

| Expert | 0.118 | 0.012 | 0.222 ** | 0.514 ** | 0.749 | |||

| Reference | 0.136 | 0.162 | 0.258 ** | 0.633 ** | 0.385 ** | 0.787 | ||

| Work Engagement | 0.138 | 0.115 | 0.171 * | 0.498 ** | 0.302 ** | 0.481 ** | 0.744 | |

| OCB | 0.118 | 0.040 | 0.244 ** | 0.307 ** | 0.321 ** | 0.332 ** | 0.669 ** | 0.836 |

| Construct | Tolerance | VIF | Construct | Tolerance | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coercive Power | 0.913 | 1.095 | Non-Coercive Power | 0.671 | 1.490 |

| Work Engagement | 0.709 | 1.410 | Dependent Variable: Organizational Citizenship Behaviors | ||

| Recommended Value | Measurement Model | |

|---|---|---|

| Fit statistic | X2/DF (≤3.000) | 2.670 |

| GFI (≥0.900) | 0.912 | |

| RMSR (≤0.050) | 0.041 | |

| RMSEA (≤0.080) | 0.039 | |

| AGFI (≥0.800) | 0.813 | |

| CFI (≥0.900) | 0.892 | |

| TLI (≥0.900) | 0.918 | |

| PGFI (≥0.600) | 0.634 | |

| Construct | Work Engagement | OCB | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coercive Power | Direct Effect | 0.15 | 0.12 |

| Indirect Effect | - | 0.01 | |

| Total Effect | 0.15 | 0.13 | |

| Non-Coercive Power | Direct Effect | 0.53 ** | 0.25 ** |

| Indirect Effect | - | 0.20 ** | |

| Total Effect | 0.53 ** | 0.45 ** | |

| Work Engagement | Direct Effect | 0.60 ** | |

| Indirect Effect | - | ||

| Total Effect | 0.60 ** | ||

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, K.O. The Relationship between Power Type, Work Engagement, and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1015. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16061015

Park KO. The Relationship between Power Type, Work Engagement, and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(6):1015. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16061015

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Kwang O. 2019. "The Relationship between Power Type, Work Engagement, and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 6: 1015. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16061015

APA StylePark, K. O. (2019). The Relationship between Power Type, Work Engagement, and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(6), 1015. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16061015