Short-Term Medical Relief Trips to Help Vulnerable Populations in Latin America. Bringing Clarity to the Scene

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

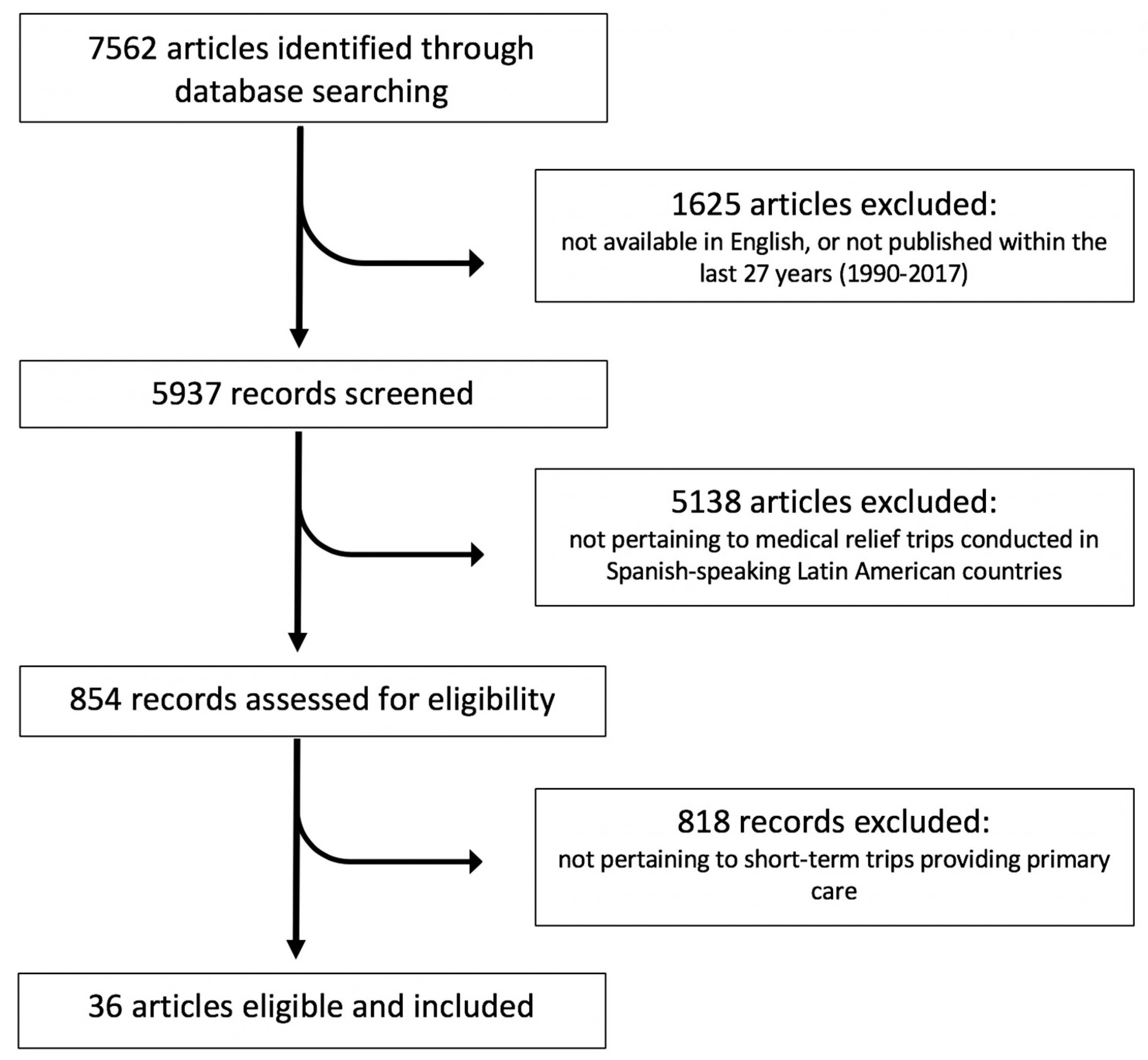

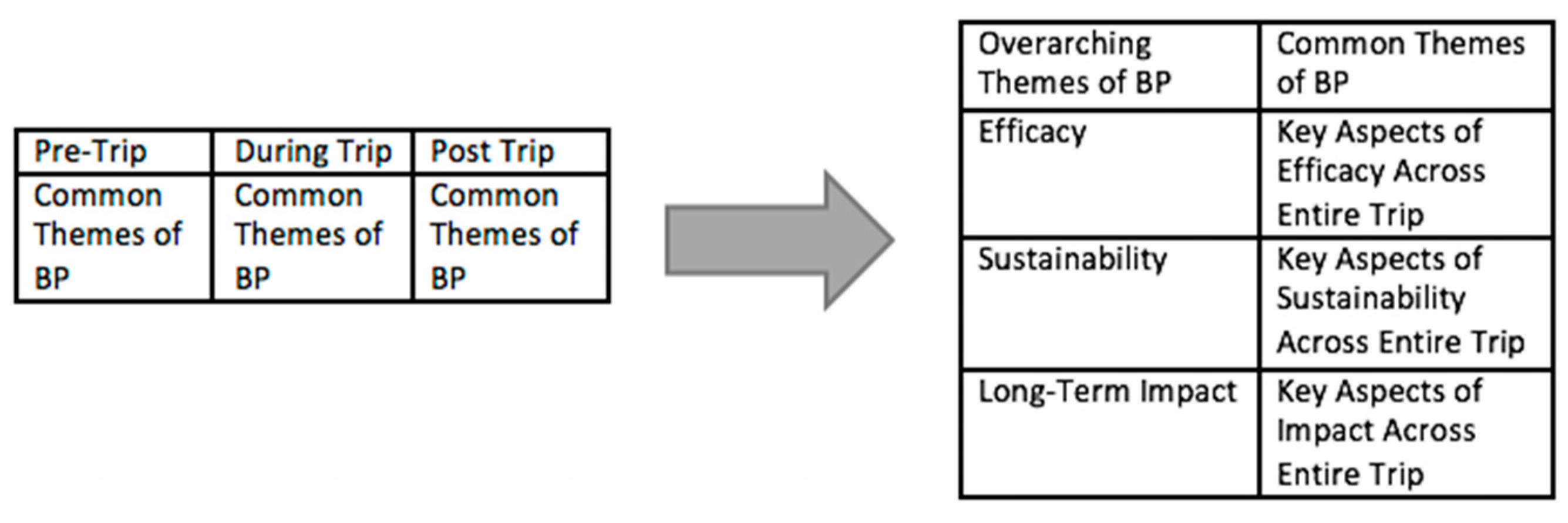

2.1. Part 1: Development of a “Best Practice” Framework for Self-Assessment

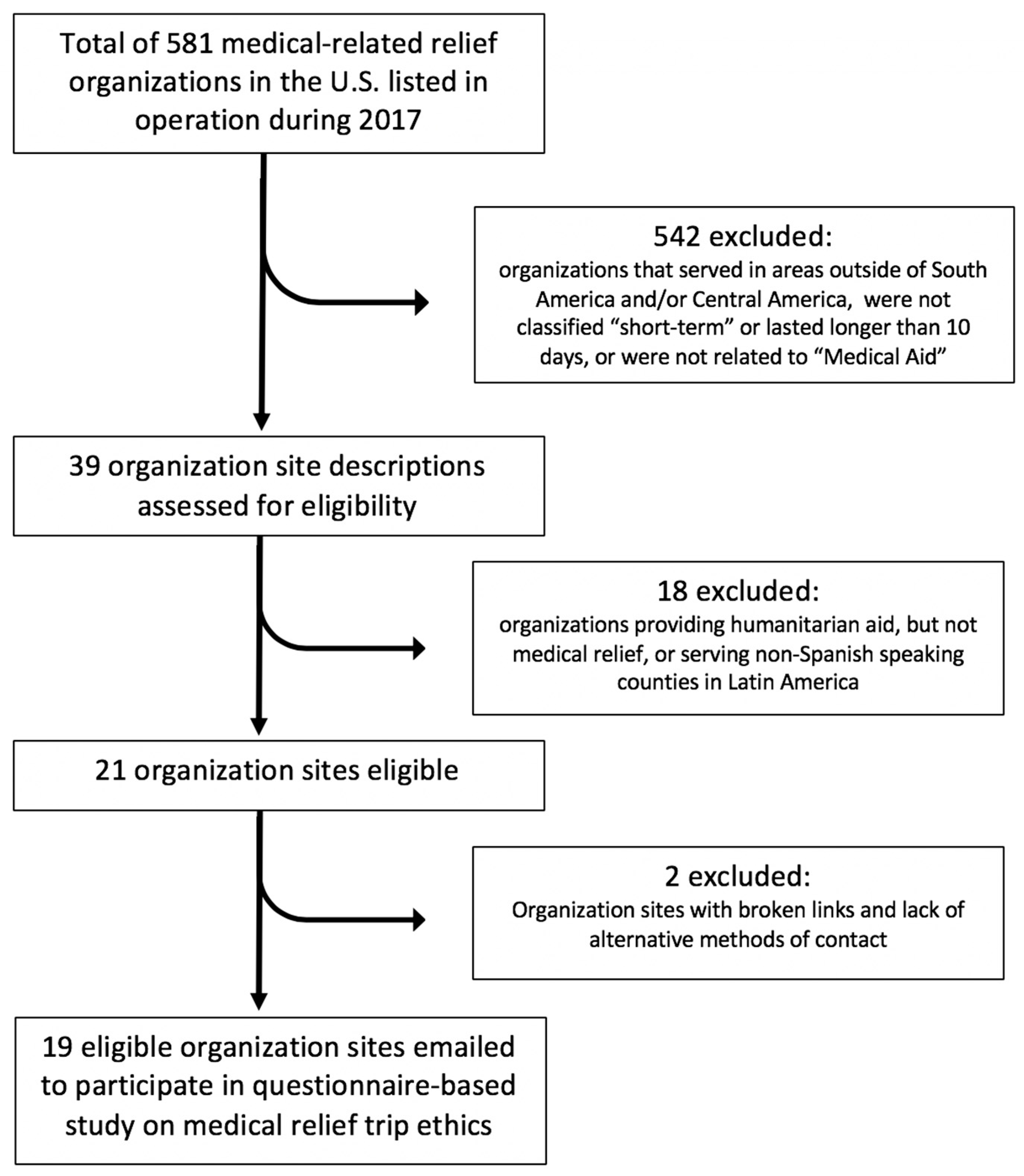

2.2. Part 2: Selection and Analysis of STMRT Organizations

2.2.1. Part 2: Sample Size Description

2.2.2. Part 2: Analysis Approach

3. Results

3.1. Part 1: Best Practice Framework

3.2. Part 2: Description of the Sample of Short-Term Medical Relief Organizations (STMRT)

3.3. Results of STMRT Organizations Content Analysis: Typology of Efficacy, Sustainability, and Impact of Medical Aid

3.3.1. Efficacy

3.3.2. Sustainability

3.3.3. Impact

3.4. Interview Results to Validate Framework

3.5. Results Summary

- Training volunteers appropriately before the trip using handouts and a pre-trip orientation

- Utilizing local translators

- Actively minimizing resource monopolization

- Certifying credentials for both medical providers and language translators

- Maintaining a sustainable revenue

- Integrating local health systems

- Creating relationships with local practitioners/NGOs

- Preparing for post-leave medical consequences

- Planning for long-term exit

- Being able to provide long-term follow care

- Respecting and adhering to local prescription attitudes

- Helping target communities become ultimately self-sufficient without their presence

- Translating all short-term goals into long-term goals

4. Discussion

Limitations. Recommendations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Operationalizing Efficacy, Sustainability, and Long-Term Impact of STMRT Organizations

| Aspects of Best Practices (BP) | Specific Questions Assessed Within Each Aspect * | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Efficacy | Acknowledges importance of cultural competence/humility? | Website mentions cultural competence/humility or respect for patient culture |

| Actively minimizes resource monopolization? | Actively minimizes resource usage per patient (in terms of financial expenditure and medical supplies); posted on websites | |

| Application necessary to join? | Website contains application or information on how to apply with qualifications | |

| Certification of practitioner credentials? | Website states organization verifies volunteer medical professionals’ credentials through some application or other method of authentication | |

| Certification of translator abilities? | Website provides application or information on how to apply with qualifications for medical translation | |

| Medical record system for all patients? | Website mentions a medical record system in place for patients served or alternative method of keeping track of returning patient history | |

| Orientation of volunteers before trips? | Whether the STMRT organization website mention requirements or existence of a pre-trip volunteer training or some type of volunteer orientation prior to the trip send-off | |

| Resources/handouts available to educate volunteers on website? | Whether the STMRT’s website mentions existence of some type of informational/guiding hand-outs prior to the trip send-off | |

| Tracks how much funding goes directly toward patient services? | Website states how much of total money raised is spent on patients | |

| Tracks number of patients served? | Website states how many patients are served | |

| Utilization of local translators? | Website states local translators are recruited and/or trained | |

| Sustainability | Board of directors/expert advisors in addition to leadership team? | Website states existence of board of directors/expert advisors |

| Disclosure of financial statements on website? | Website discloses financial statements | |

| Integration of local health systems? | Website states collaboration/integration with local health systems, or manner or having checked for the existence of local medical services in their chosen communities | |

| Minimizes expenditure on administration budget? (measured as <10% of total revenue) | Administrative budget information from released IRS tax forms (Form 990) for each of the 19 STMRT organizations | |

| Programs on community health and/or public health? | Website states interaction with and/or creation of community/public health programs | |

| Registered as official 501(c)(3) charity/non-profit? | Verified through GuideStar, a website based at guidestar.org that provides the world’s largest source of information about non-profit organizations and organization’s last released public IRS Form 990 | |

| Sustainable (positive) revenue? | Checked against released IRS tax forms (Form 990) by subtracting total expenditures (i.e., administrative costs) from total revenue (i.e., donations) | |

| Transparent executive statements of funding diagrams available on website? | Website provides transparent executive statements on funding | |

| Working relationships with local medical practitioners? | Website states working relationships with local practitioners | |

| Working relationships with local NGOs? | Website states working relationships with local NGOs | |

| Impact | Ability to provide long-term follow-up care? | Website states method of long-term follow-up care |

| Accredited by third-party audits? | Verified through GuideStar by searching listed accreditations for each organization, as well as referencing the organization’s website itself | |

| Actively acknowledges not imposing religious ideas on patients served? | Website explicitly acknowledges that organization will not impose or force ideas (religious-based) on patients served during the trip by any of its volunteers | |

| Explicitly states non-discriminatory policy or service? | Website states organization is equally willing to provide the same quality and level of care to patients that may be of a different religion, culture, or belief system | |

| Plans for long-term exit? | Website mentions idea of long-term exit | |

| Plans for sustainable and independent local healthcare? | Website mentions helping local healthcare system to become sustainable and independent | |

| Preparation for post-leave medical consequences? | Website states plans/preparation to deal with post-leave medical consequences | |

| Respect and/or adherence for local-based prescription attitudes? | Website states organization respects/adheres to local-based prescription attitudes | |

| Sustainability/long-term impact mentioned in mission statement? | Website mentions sustainability/long-term impact ideas in mission statement | |

| Training of local medical and non-medical counterparts? | Website mentions training of local counterparts | |

| Translation of all short-term goals into long-term goals? | Website states eventual long-term goals |

References

- Levin, M. Healing the Children: Medical Missions. Lancet 1996, 348, 1712–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prognosis E-News. WHSO Student Groups Preparing for Latin America Medical Missions. Prognosis E-News, 8 December 2008.

- Crump, J.A.; Sugarman, J. Ethical Considerations for Short-term Experiences by Trainees in Global Health. JAMA 2008, 300, 1456–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsey, K.M.; Weijer, C. Ethics of Surgical Training in Developing Countries. World J. Surg. 2007, 31, 2067–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, A.S. Medical Missions: A Therapeutic Primer. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2012, 66, E5–E8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Overseas Elective: Purpose or Picnic? Lancet 1993, 342, 753–754. [CrossRef]

- Maki, J.; Qualls, M.; White, B.; Kleefield, S.; Crone, R. Health Impact Assessment and Short-term Medical Missions: A Methods Study to Evaluate Quality of Care. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2008, 8, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyons, K.; Hanley, J.; Wearing, S.; Neil, J. Gap Year Volunteer Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopinak, J.K. Humanitarian Aid: Are Effectiveness and Sustainability Impossible Dreams? J. Humanit. Assist. 2013, 10. Available online: https://sites.tufts.edu/jha/archives/1935 (accessed on 8 March 2017).

- Abenavoli, F.M. Improving Humanitarian Medical Mission Efficacy. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2012, 129, 559e–560e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martiniuk, A.L.; Manouchehrian, M.; Negin, J.A.; Zwi, A.B. Brain Gains: A Literature Review of Medical Missions to Low and Middle-income Countries. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jobe, K. Disaster relief in post-earthquake Haiti: Unintended consequences of humanitarian volunteerism. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2011, 9, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamat, D.; Armstrong, R.W. Global Child Health: An Essential Component of Residency Training. J. Pediatrics 2006, 149, 735–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banatvala, N.; Doyal, L. Knowing When to Say “No” on the Student Elective. BMJ 1998, 316, 1404–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbieri, C.; Santos, C.A.; Katsube, Y. Volunteer Tourism: On-the-ground Observations from Rwanda. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.K.; Harper, P.R.; Potts, C.N.; Thyle, A. Planning Sustainable Community Health Schemes in Rural Areas of Developing Countries. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2009, 193, 768–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezruchka, S. Medical Tourism as Medical Harm to the Third World: Why? For Whom? Wilderness Environ. Med. 2000, 11, 77–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, S.R.; Ziccardi, V.B.; Chuang, S. Survey of Residents Who Have Participated in Humanitarian Medical Missions. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2012, 70, E147–E157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sin, H.L. Volunteer Tourism—“Involve Me And I Will Learn”? Ann. Tour. Res. 2009, 36, 480–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solheim, J.; Edwards, P. Planning a Successful Mission Trip: The Ins and Outs. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2007, 33, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, S.-U.; Smith, D.K. Use of Location-allocation Models in Health Service Development Planning in Developing Nations. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2000, 123, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lough, B.J. International Volunteers’ Perceptions of Intercultural Competence. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2011, 35, 452–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markel, H. Albert Schweitzer, a Renowned Medical Missionary with a Complicated History. PBS, 14 January 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, L.M. Short-Term Medical Missions: Enhancing or Eroding Health? Missiol. Int. Rev. 1993, 21, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesus, J.E. Ethical Challenges and Considerations of Short-Term International Medical Initiatives: An Excursion to Ghana as a Case Study. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2010, 55, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garbern, S. Medical Relief Trips...What’s Missing? Exploring Ethical Issues and the Physician-Patient Relationship. EJBM 2010, 25, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebauer, R. Medical Mission Trip to Kenya. Cor Et Vasa 2012, 54, E57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, A. Medical Missions: What Makes Us Think We’re Qualified? Student Doctor Network, 11 July 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Caniza, M.A.; Clara, W.; Maron, G.; Navarro-Marin, J.E.; Rivera, R.; Howard, S.C.; Camp, J.; Barfield, R.C. Establishment of Ethical Oversight of Human Research in El Salvador: Lessons Learned. Lancet Oncol. 2006, 7, 1027–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battat, R.; Seidman, G.; Chadi, N.; Chanda, M.Y.; Nehme, J.; Hulme, J.; Li, A.; Faridi, N.; Brewer, T.F. Global Health Competencies and Approaches in Medical Education: A Literature Review. BMC Med. Educ. 2010, 10, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unite for Sight. Module 8: The Significant Harm of Worst Practices. Unite for Sight, 16 January 2009.

- Wilkinson, D.; Symon, B. Medical Students, Their Electives, and HIV. BMJ 1999, 318, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comninellis, N. Are Short-Term Medical Missions Effective? Institute for International Medicine, INMED: Sterling, VA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, C.; Mosavel, M.; van Stade, D. Ethical Challenges in the Design and Conduct of Locally Relevant International Health Research. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 64, 1960–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suchdev, P.; Ahrens, K.; Click, E.; Macklin, L.; Evangelista, D.; Graham, E. A Model for Sustainable Short-Term International Medical Trips. Ambul. Pediatrics 2007, 7, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, C.S. So You Want to Go on a Medical Mission. J. Nurse Pract. 2007, 3, 707–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, E.; Doocy, S. International Short-term Medical Service Trips: Guidelines from the Literature and Perspectives from the Field. World Health Popul. 2010, 12, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, S.B. Ethical Coherency When Medical Students Work Abroad. Lancet 2008, 372, 1133–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A.; Sullivan, M.; Sherman, R.; Magee, W.P. The Medical Mission and Modern Cultural Competency Training. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2011, 212, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conran, M. They Really Love Me! Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 1454–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, D. Chinua Achebe’s Encounters with Many Hearts of Darkness. The New York Times, 15 December 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zervos, J.M. Maximizing the Efficacy of Short Term Medical Missions. The Huffington Post, 18 April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- McKinsey & Company. Measuring What Matters in Nonprofits; McKinsey & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dedoose User Guide. Available online: https://www.dedoose.com/userguide (accessed on 11 March 2017).

- Mixed Methods Research Designs. Research Rundowns, 19 July 2009.

| Characteristics of STMRT Organizations | Number (and %) of STMRT Organizations |

|---|---|

| Size: | |

| <3 staff | 3 (15.79%) |

| 3–10 staff | 9 (47.37%) |

| >10 staff | 7 (36.84%) |

| Religion: | |

| Affiliated: | 14 (73.68%) |

| Baptist | 1 (5.26%) |

| Catholic | 1 (5.26%) |

| Christian | 12 (63.16%) |

| Non-affiliated | 5 (26.32%) |

| Type of organization: | |

| 501(C)(3) non-profit charity | 18 (94.74%) |

| Not registered | 1 (5.26%) |

| Website availability: | |

| Functional website | 18 (94.74%) |

| Non-functional website | 1 (5.26%) |

| Aspects of Best Practices (BP) | Specific Questions Assessed Within Each Aspect * | # Organizations Meeting | % of Organizations Meeting Best Practices (BP) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 80–100% BP | 30–79% BP | 0–29% BP | |||

| Efficacy | Acknowledges importance of cultural competence/humility? | 5 | 21.05% (4) | 57.89% (11) | 21.05% (4) |

| Actively minimizes resource monopolization? | 2 | ||||

| Application necessary to join? | 19 | ||||

| Certification of practitioner credentials? | 19 | ||||

| Certification of translator abilities? | 9 | ||||

| Medical record system for all patients? | 12 | ||||

| Orientation of volunteers before trips? | 9 | ||||

| Resources/handouts available to educate volunteers on website? | 6 | ||||

| Tracks how much funding goes directly toward patient services? | 6 | ||||

| Tracks number of patients served? | 19 | ||||

| Utilization of local translators? | 3 | ||||

| Sustainability | Board of directors/expert advisors in addition to leadership team? | 13 | 15.79% (3) | 57.89% (11) | 26.32% (5) |

| Disclosure of financial statements on website? | 6 | ||||

| Integration of local health systems? | 3 | ||||

| Minimizes expenditure on administration budget? (measured as <10% of total revenue) | 16 | ||||

| Programs on community health and/or public health? | 7 | ||||

| Registered as official 501(c)(3) charity/non-profit? | 18 | ||||

| Sustainable (positive) revenue? | 11 | ||||

| Transparent executive statements of funding diagrams available on website? | 6 | ||||

| Working relationships with local medical practitioners? | 2 | ||||

| Working relationships with local NGOs? | 2 | ||||

| Impact | Ability to provide long-term follow-up care? | 4 | 15.79% (3) | 26.32% (5) | 57.89% (11) |

| Accredited by third-party audits? | 9 | ||||

| Actively acknowledges not imposing religious ideas on patients served? | 1 | ||||

| Explicitly states non-discriminatory policy or service? | 8 | ||||

| Plans for long-term exit? | 3 | ||||

| Plans for sustainable and independent local healthcare? | |||||

| Preparation for post-leave medical consequences? | 3 | ||||

| Respect and/or adherence for local-based prescription attitudes? | 2 | ||||

| Sustainability/long-term impact mentioned in mission statement? | 8 | ||||

| Training of local medical and non-medical counterparts? | 6 | ||||

| Translation of all short-term goals into long-term goals? | 3 | ||||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheng, M.Y.; Rodriguez, E. Short-Term Medical Relief Trips to Help Vulnerable Populations in Latin America. Bringing Clarity to the Scene. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 745. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16050745

Cheng MY, Rodriguez E. Short-Term Medical Relief Trips to Help Vulnerable Populations in Latin America. Bringing Clarity to the Scene. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(5):745. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16050745

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Melodyanne Y., and Eunice Rodriguez. 2019. "Short-Term Medical Relief Trips to Help Vulnerable Populations in Latin America. Bringing Clarity to the Scene" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 5: 745. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16050745

APA StyleCheng, M. Y., & Rodriguez, E. (2019). Short-Term Medical Relief Trips to Help Vulnerable Populations in Latin America. Bringing Clarity to the Scene. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(5), 745. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16050745