Remote Implementation of a School-Based Health Promotion and Health Coaching Program in Low-Income Urban and Rural Sites: Program Impact during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Program Description

2.2. SYDCP Adaptation for Remote Implementation

2.3. Participant Recruitment

2.4. Program Implementation

2.4.1. San Jose, CA

2.4.2. Central Valley, CA

2.4.3. Lawrence County, MO

2.5. Target Population

2.6. Outcome Measures

2.7. Sample Size Determination

2.8. Data Analysis

3. Results

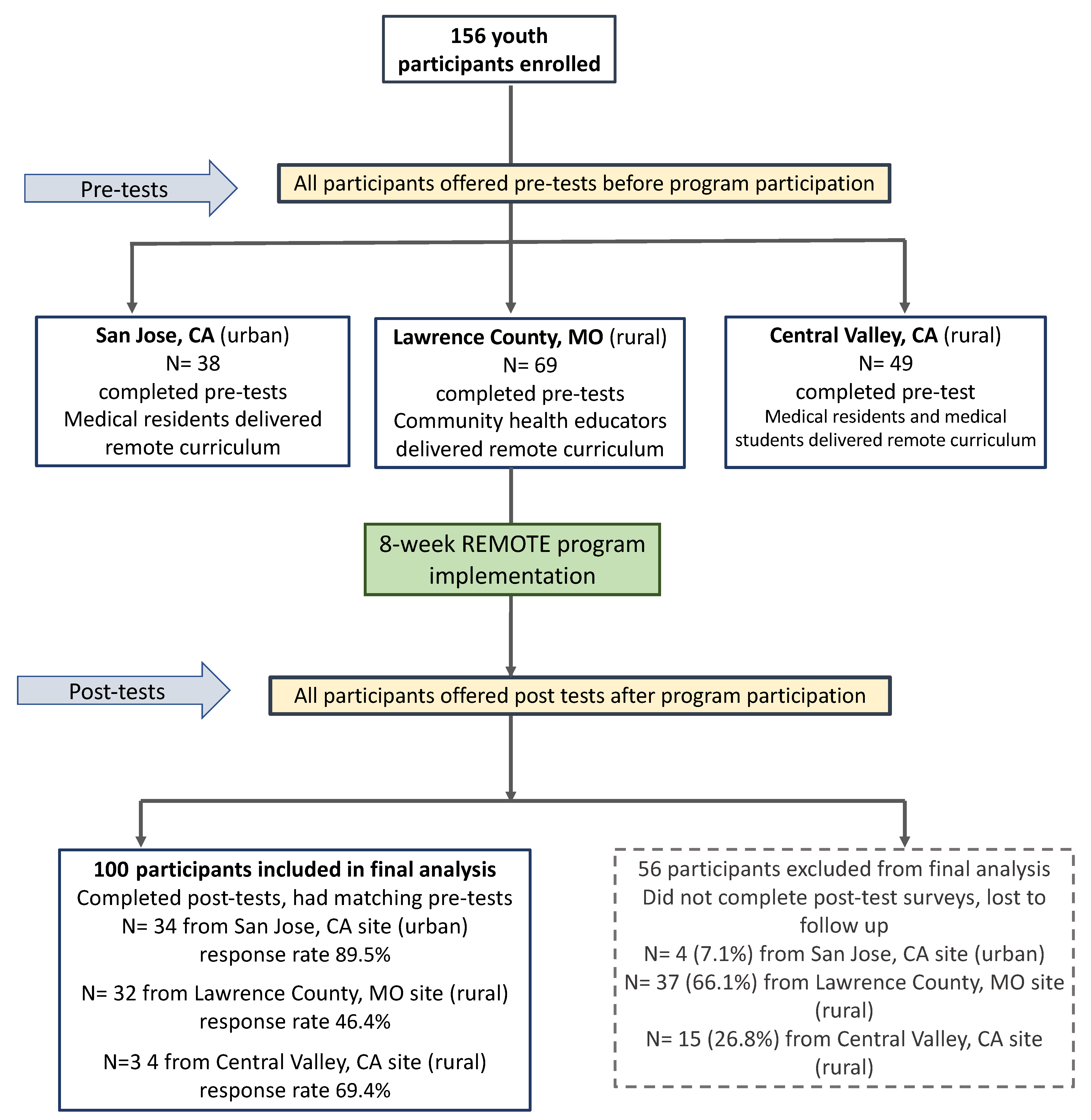

3.1. Remote Participation

3.2. Participants Lost to Follow-Up

3.3. Outcome Measures

3.3.1. Health Knowledge

3.3.2. Patient Activation

3.3.3. Health Communication and Understanding

3.3.4. Health Behaviors

3.3.5. Psycho-Social Assets

3.3.6. Lifestyle Change

3.3.7. Inter-Site Outcome Differences

3.4. Results of Multivariate Linear Regression

3.5. Qualitative Analysis

One of the action plans that I made as a part of this program was healthy eating, which was based off of the plate rule (1/2 low carbs veggies, 1/4 protein rich foods, and 1/4 high in carbs). I started with 2 meals a day with this method, at least 4–5 days a week at my designated eating times. I meal prepped so it was less stressful, and it worked very well!

One action plan is to exercise more with my aunt. For example, we went to walk every day for about 1 h and did zumba for 30 min after. Also, to eat healthier, we both stopped eating junk food 4 days a week and started drinking 3 water bottles every day.

I realized how much sleep could affect my lifestyle and life span. I am starting to get more sleep and prioritizing my night routine. I tried a sleep mask and going to bed earlier. I now get around 7–8 h of sleep which is a big change from before.

I start eating less snacks in between meals and started being more active by playing more with my dogs.

As a part of this program, I created various action plans for my grandfather and I. For my grandfather, we worked on a walking plan to incorporate more walking and stretching into his schedule because he has to sit for the entire duration of his work on a tractor, he decided on splitting a bit of time during his lunches to stretch and take a light walk around the tractor, then once at home off of work, another walk around the ranch, he made this plan to fit into 6 out of the 7 days. We also made an action plan to incorporate daily breathing techniques that he would incorporate into the beginning of the day before breakfast and at the end of the day right before bed which was reminded with an alarm. For myself, I made an action plan to start running five times a week after a light breakfast at 6 am. I cut down my brownie/cookie intake only having 1–2 after lunch every other day. I also increased the amount of water I drank by replacing soda with water with lemon.

Changes I have made are eating healthier, going to bed earlier and putting my phone down at least 10 min before going to sleep, and reducing stress by taking time to breathe. When it comes to healthier eating, I have started to not buy snack foods like chips and I have started reading food labels. With reducing stress, I have made sure to wake up 5 min earlier to take a couple deep breaths before getting ready for the day.

3.6. Additional Participant Feedback Regarding Program Benefit

4. Discussion

5. Study Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The Lancet: Latest Global Disease Estimates Reveal Perfect Storm of Rising Chronic Diseases and Public Health Failures Fueling COVID-19 Pandemic. Available online: https://www.healthdata.org/news-release/lancet-latest-global-disease-estimates-reveal-perfect-storm-rising-chronic-diseases-and (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Kirby, T. Evidence mounts on the disproportionate effect of COVID-19 on ethnic minorities. Lancet 2020, 8, 547–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer-Davis, E.J.; Lawrence, J.M.; Dabalea, D.; Divers, J.; Isom, S.; Dolan, L.; Imperatorre, G.; Linder, B.; Marcovina, S.; Pettitt, D.; et al. Incidence trends of type 1 and type 2 diabetes among youths, 2002–2012. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1419–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, D.M.; Anyane-Yeboa, A.; Balzora, S.; Issaka, R.B.; May, F.P. COVID-19 and the other pandemic: Populations made vulnerable by systemic inequity. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 17, 520–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, M.W.; Nápoles, A.M.; Pérez-Stable, E.J. COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities. JAMA 2020, 323, 2466–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndumbe-Eyoh, S.; Muzumdar, P.; Betker, C.; Oickle, D. ‘Back to better’: Amplifying health equity, and determinants of health perspectives during the COVID-19 pandemic. Glob. Health Promot. 2021, 28, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, S.; Biswas, P.; Ghosh, R.; Chatterjee, S.; Dubey, M.J.; Chatterjee, S.; Lahiri, D.; Lavie, C.J. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020, 14, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, A.; Tribble, A.G. The path ahead: From global pandemic to health promotion. Prev. Med. Rep. 2021, 21, 101271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, S.W.; Henkhaus, L.E.; Zickafoose, J.S.; Lovell, K.; Halvorson, A.; Loch, S.; Letterie, M.; Davis, M.M. Well-being of parents and children during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national survey. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e2020016824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, N.T.; Snethen, J.A.; Greenberg, C.S.; Frenn, M.; Kilanowski, J.F.; Gance-Cleveland, B.; Burke, P.J.; Lewandowski, L. When pandemics collide: The impact of COVID-19 on childhood obesity. J. Pediat. Nurs. 2021, 56, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolford, S.J.; Sidell, M.; Li, X.; Else, V.; Young, D.R.; Resnicow, K.; Koebnick, C. Changes in Body Mass Index Among Children and Adolescents During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA 2021, 326, 1434–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maestripieri, L. The COVID-19 Pandemics: Why intersectionality matters. Front. Sociol. 2021, 6, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielli, J.; Lund, E. Acute-on-chronic stress in the time of COVID-19: Assessment considerations for vulnerable youth populations. Pediatr. Res. 2020, 88, 829–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serving Youth Remotely. Available online: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/103944/serving-youth-remotely_strategies-for-practitioners_resource-guide_0.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Kwankam, S.Y. What e-Health can offer. Bull. World Health Organ. 2004, 82, 800–801. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chesser, A.; Burke, A.; Reyes, J.; Rohrberg, T. Navigating the digital divide: A systematic review of eHealth literacy in underserved populations in the United States. Inform. Health Soc. Care. 2016, 41, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.; Martinasek, M.; Carone, K.; Sanders, S. High School Students’ Perceptions of Traditional and Online Health and Physical Education Courses. J. Sch. Health. 2020, 90, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, M.; Dryden, E.M.; Horan, C.M.; Price, S.; Marshall, R.; Hacker, K.; Finkelstein, J.A.; Taveras, E.M. Leveraging text messaging and mobile technology to support pediatric obesity-related behavior change: A qualitative study using parent focus groups and interviews. JMIR 2013, 15, e272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stohlman, S.L.; Cornell, D.G. An online educational program to increase student understanding of threat assessment. Int. J. Sch. Health 2019, 89, 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedele, D.A.; Cushing, C.C.; Fritz, A.; Amaro, C.M.; Ortega, A. Mobile health interventions for improving health outcomes in youth: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2017, 171, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimers, F.M.; Schleicher, A. A Framework to Guide an Education Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic of 2020; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gefter, L.; Morioka-Douglas, N.; Srivastava, A.; Rodriguez, E. Supporting At-Risk Youth and Their Families to Manage and Prevent Diabetes: Developing a National Partnership of Medical Residency Programs and High Schools. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0158477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefter, L.; Rosas, L.G.; Rodriguez, E.; Morioka-Douglas, N. Training at-risk youth to become diabetes self-management Coaching for family members: Partnering family medicine residents with underserved schools. Diabetes Educ. 2014, 40, 786–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefter, L.R.; Morioka-Douglas, N.; Srivastava, A.; Rodriguez, E. Increasing patient activation scores of vulnerable youth by partnering medical residency programs with public high schools. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021, 104, 927–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorig, K.R.; Sobel, D.S.; Ritter, P.L.; Laurent, D.; Hobbs, M. Effect of a self-management program on patients with chronic disease. Eff. Clin. Pract. 2001, 4, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986; pp. 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Thom, D.H.; Ghorob, A.; Hessler, D.; De Vore, D.; Chen, E.; Bodenheimer, T.A. Impact of peer health coaching on glycemic control in low-income patients with diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. Ann. Fam. Med. 2013, 11, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defining Rural at the U.S. Census Bureau. Available online: https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/reference/ua/Defining_Rural.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Nicholson, L.M.; Slater, S.J.; Chriqui, J.F.; Chaloupka, F. Validating adolescent socioeconomic status: Comparing school free or reduced price lunch with community measures. Spat. Demogr. 2014, 2, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ed Data Education Data Partnership. Available online: https://www.ed-data.org/ (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Public School Review. Available online: https://www.publicschoolreview.com/ (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- K-12 School and District Rankings. Available online: https://www.niche.com/k12/rankings/ (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Fitzgerald, J.T.; Funnell, M.M.; Anderson, R.M.; Nwankwo, R.; Stansfield, R.B.; Piatt, G.A. Validation of the revised brief diabetes knowledge test (DKT2). Diabetes Educ. 2016, 42, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothman, R.L.; Malone, R.; Bryant, B.; Wolfe, C.; Padgett, P.; DeWalt, D.A.; Weinberger, M.; Pignone, M. The spoken knowledge in low literacy in diabetes scale. Diabetes Educ. 2005, 31, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insignia Health. Increasing Activation Starts with Measurement. Available online: https://s3.amazonaws.com/insigniahealth.com-assets/PAM-Fact-Sheet.20200505.pdf?mtime=20200505094829&focal=none (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Gefter, L.; Morioka-Douglas, N.; Srivastava, A.; Jiang, C.A.; Rodriguez, E. Remote Implementation of a Health Promotion Program in an Underserved High School during COVID-19: Lessons Learned. J. Pediatr. Health Car. 2021, 6, 1045. [Google Scholar]

- California Healthy Kids Survey. Available online: https://www.cde.ca.gov/ls/he/at/chks.asp (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Stanford Mind and Body Lab. Available online: https://mbl.stanford.edu/ (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Rosenberg, M. Rosenberg, M. Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSE). In Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Measures Package; University of Wollongong: Wollongong, NSW, Australia, 1965; p. 61. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard, J.H.; Greene, J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: Better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Aff. 2013, 32, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PAM Reliably Predicts Future ER Visits, Hospital Admissions and Readmissions, Medication Adherence and More. Available online: https://www.insigniahealth.com/products/pam-survey (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Carolina Farm Stewards Survey, Appendix F: Surveys and Interview Questions. Available online: https://www.carolinafarmstewards.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Appendices-F-I.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- PRAPARE: Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patients’ Assets, Risks, and Experiences. Available online: https://prapare.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/PRAPARE-English.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Strauss, A.L.; Corbin, J.M. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kinney, R.L.; Lemon, S.C.; Person, S.D.; Pagot, S.L.; Saczynski, J.S. The association between patient activation and medication adherence, hospitalization, and emergency room utilization in patients with chronic illnesses: A systematic review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2015, 98, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosen, D.M.; Schmittdiel, J.; Hibbard, J.; Sobel, D.; Remmers, C.; Bellows, J. Is Patient Activation Associated with Outcomes of Care for Adults with Chronic Conditions? J. Ambul. Care Manag. 2007, 30, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J.; Hibbard, J.H.; Sacks, R.; Overton, V.; Parrotta, C.D. When patient activation levels change, health outcomes and costs change, too. Health Aff. 2015, 34, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baiocchi-Wagner, E.A.; Talley, A.E. The Role of Family Communication in Individual Health Attitudes and Behaviors Concerning Diet and Physical Activity. Health Commun. 2013, 28, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leffert, N.; Benson, P.L.; Scales, P.C.; Sharma, A.R.; Drake, D.R.; Blyth, D.A. Developmental assets: Measurement and prediction of risk behaviors among adolescents. Appl. Dev. Sci. 1998, 2, 209–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, L.G.; Flisher, A.J.; Bhana, A.; Lombard, C. Associations among adolescent risk behaviours and self-esteem in six domains. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2004, 45, 1454–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salam, R.A.; Hooda, M.; Das, J.K.; Arshad, A.; Lassi, Z.S.; Middleton, P.; Bhutta, Z.A. Interventions to Improve Adolescent Nutrition: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 59, S29–S39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, A.; Batada, A. Exploring stress and coping among urban African American adolescents: The Shifting the Lens study. PCD 2006, 3, A40. [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone, J.M.; Roake, C.; Sheikh, I.; Mole, A.; Nigg, J.T.; Oken, B. School-based mindfulness intervention for stress reduction in adolescents: Design and methodology of an open-label, parallel group, randomized controlled trial. Contemp. Clin. 2016, 4, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobile Technology and Home Broadband 2021, Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/06/03/mobile-technology-and-home-broadband-2021/ (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Patel, H.; Masten, K.; Chambers, R.; Edwards, A.; Fleszar, L.; Harvey, B.; Dunn, J.; Nelson, D.; Goldtooth, T.; James, M.; et al. Feasibility and Acceptability of Virtual Implementation of a Sexual Reproductive Health Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program for Native Youth. Am. Indian Alsk. Native Ment. Health Res. 2022, 29, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parekh, J.; McClay, A.; Faccio, B.; Gates, C.; Garcia, J.; Coryell, A.; Manlove, J. Adapting an in-person sexual health program for a virtual setting. Child Trends 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, C.C.; White, L.; Schmidt, T.; Rataj, S.; McEachern, D.; Wisnieski, D.; Garnie, J.; Kirk, T.; Moto, R.; Wexler, L. Adapting PC CARES to continue suicide prevention in rural Alaska during the COVID-19 pandemic: Narrative overview of an in-person community-based suicide prevention program moving online. Am. Indian Alsk. Native Ment. Health Res. 2022, 29, 126–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Outcomes | Measures Used |

|---|---|

| Health Knowledge: Change in health knowledge (general and diabetes-related) | 8 questions adapted from Diabetes Knowledge Test by U. Michigan’s Diabetes Institute [33], the Spoken Knowledge in Low Literacy in Diabetes scale [34], and questions developed by authors [22] |

| Patient Activation Change in patient activation scores and levels | 10-item Patient Activation Measure PAM ® 10 from Insignia Health [35] |

| Health Communication and Understanding | 3 questions developed by the authors [36] |

| Health Behavior: Change in daily physical activity Change in daily consumption of cups of fruits and vegetables Change in consumption of sugary drinks/foods and fatty foods Change in ability to manage stress | 7 questions adapted from California Healthy Kids Survey Physical Health Module 2021 [37] and Stanford Mind and Body Lab [38] |

| Youth Assets: Self-Esteem Change in self-esteem | 10-item Rosenberg Scale for self-esteem [39] |

| Self-efficacy Change in self-efficacy | 4 questions adapted from California Healthy Kids’ Survey [37] |

| Problem-solving Change in problem solving ability | 3 questions adapted from California Healthy Kids’ Survey [37] |

| Lifestyle Change: Specific healthy behavior change(s) | 1 open-ended question developed by authors to qualitatively analyze lifestyle change(s) made after program participation |

| Combined Sample n = 100 | Urban Site San Jose, CA n = 34 | Rural Site Lawrence County, MO n = 32 | Rural Site Central Valley, CA n = 34 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| Male | 16 (16.0%) | 3 (8.8%) | 6 (18.8%) | 7 (20.6%) |

| Female | 84 (84.0%) | 31 (91.2%) | 26 (81.3%) | 27 (79.4%) |

| Grade | ||||

| 9th | 16 (16.0%) | 9 (26.5%) | 3 (9.4%) | 4 (11.8%) |

| 10th | 14 (14.0%) | 10 (29.4%) | 3 (9.4%) | 1 (2.9%) |

| 11th | 45 (45.0%) | 4 (11.8%) | 15 (46.9%) | 26 (76.5%) |

| 12th | 25 (25.0%) | 11 (32.4%) | 11 (34.4%) | 3 (8.8%) |

| Age (mean age in years) | 16.05 years | 15.47 years | 16.5 years | 16.21 years |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 40 (40%) | 7 (20.6%) | 15 (46.9%) | 19 (55.9%) |

| Race | ||||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1(2.9%) |

| Asian | 28 (28.0%) | 22 (64.7%) | 1 (3.1%) | 5 (14.7%) |

| Black or African American | 3 (3.0%) | 2 (5.9%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.9%) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.9%) |

| White | 37 (37.0%) | 1 (2.9%) | 20 (62.5%) | 16 (47.1%) |

| Two or more races | 7 (7.0%) | 4 (11.8%) | 1 (3.1%) | 2 (5.9%) |

| Declined to respond | 23 (23.0%) | 5 (14.7%) | 10 (31.3%) | 8 (23.5%) |

| Other Sample Characteristics | ||||

| Live within 15 min to place where shop for food | 77 (77%) | 25 (73.5%) | 29 (90.6%) | 23 (67.6%) |

| Access to fresh fruits and vegetables most times | 93 (93%) | 31 (91.2%) | 31 (96.9%) | 31 (91.2%) |

| Migrant work not main source of family income | 87 (87%) | 31 (91.2%) | 28 (87.5%) | 28 (82.4%) |

| Person Coached * | ||||

| Parent | 45 (45 %) | 12 (35.3%) | 16 (50%) | 17 (50%) |

| Other family member | 31 (31%) | 11(32.4%) | 9 (28.1%) | 11 (32.4%) |

| Friend or other | 21 (21.0%) | 11 (32.4%) | 6 (18.8%) | 4 (11.8%) |

| Person coached had diabetes | 26 (26.0%) | 7 (20.6%) | 10 (31.3%) | 9 (26.5%) |

| All Combined n = 100 | San Jose, CA (Urban) n = 34 | Rural Site Lawrence County, MO n = 32 | Rural Site Central Valley, CA n = 34 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evaluation Measures/Outcomes | Mean difference (SD) | Mean difference (SD) | Mean difference (SD) | Mean difference (SD) |

| 1 Health Knowledge | 3.55 (2.08) ** | 3.676 (1.6) ** | 3.75 (2.1) ** | 3.235 (2.4) ** |

| Patient Activation Measure (n = 92) | ||||

| 2 PAM 10® mean scores | 11.66 (15.05) ** | 9.22 (15.7) ** | 10.72 (15.5) ** | 14.76 (13.8) ** |

| Health communication and understanding | ||||

| 3 Talking about health at home | 0.230 (0.89) * | 0.059 (0.92) | 0.219 (0.75) | 0.412 (0.98) * |

| 4 Understanding health improvement | 0.290 (0.91) ** | 0.176 (0.99) | 0.281 (1.05) | 0.412 (0.65) ** |

| Health Behaviors | ||||

| 5 Physical Activity | 0.270 (1.99) | −0.088 (1.5) | 0.656 (2.4) | 0.265 (1.9) |

| 6 Fruit and vegetable consumption | 0.290 (0.98) ** | 0.147 (0.96) | 0.438 (1.16) * | 0.294 (0.83) * |

| 7 Consumption of sugary drinks | −0.18 (1.03) | −0.353 (0.98) * | −0.062 (0.94) | −0.118 (1.15) |

| 8 Consumption of sugary foods | −0.17 (1.3) | −0.382 (0.98) * | −0.094 (1.2) | −0.029 (1.22) |

| 9 Consumption of fatty foods | −0.1 (1.0) | −0.147 (.82) | −0.406 (1.0) * | 0.235 (1.1) |

| 10 Ability to reduce stress | 0.360 (1.18) ** | 0.176 (1.06) | 0.313 (1.3) | 0.588 (1.2) * |

| Youth Assets | ||||

| 11 Self-esteem | 1.2 (3.47) ** | 0.265 (3.5) | 1.438 (3.09) * | 1.912 (3.6) ** |

| 12 Self-efficacy | 0.810 (2.03) ** | 0.353 (2.3) | 0.844 (1.7) * | 1.235 (1.94) ** |

| 13 Problem solving (2 questions) | 0.47 (1.49) ** | 0.088 (1.5) | 0.50 (1.3) * | 0.824 (1.5) ** |

| 14 Problem solving (1 question) | 0.290 (0.74) ** | 0.235 (0.69) | 0.188 (0.78) | 0.441 (0.74) ** |

| Outcome Category | Predictor Variables | Coefficient (SE) | Confidence Intervals (Lower, Upper) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health Knowledge | Pre-test score | −0.756 (0.112) ** | −0.977, −0.534 |

| Grade (ref = 9th and 10th grade) | 0.341 (0.422) | −0.496, 1.179 | |

| Gender (ref = male) | 0.149 (0.482) | −0.809, 1.106 | |

| Location (ref = urban) | |||

| Rural MO | −0.679 (0.475) | −1.622, 0.264 | |

| Rural Central Valley | −0.320 (0.462) | −1.237, 0.598 | |

| Patient Activation Measure (n = 92) | |||

| PAM®10 (n = 92) | PAM®10 pre-test score | 0.782 (0.142) ** | 0.499, 1.064 |

| Grade (ref = 9th and 10th grade) | 0.111 (3.835) | −7.513, 7.736 | |

| Gender (ref = male) | 4.67 (4.446) | −4.17, 13.508 | |

| Location (ref = urban) | |||

| Rural MO | 1.974 (4.24) | −6.46, 10.407 | |

| Rural Central Valley | 6.563 (4.12) | −1.623, 14.75 | |

| Health communication and understanding | |||

| Talking about health at home | Pre-test score | −0.703 (0.080) ** | −0.863, −0.543 |

| Grade (ref = 9th and 10th grade) | −0.340 (0.158) * | −0.654, −0.026 | |

| Gender (ref = male) | 0.026 (0.185) | −0.340, 0.393 | |

| Location (ref = urban) | |||

| Rural MO | 0.170 (0.175) | −0.178.517, | |

| Rural Central Valley | 0.641 (0.175) ** | 0.293, 0.988 | |

| Understanding of health | Pre-test score | −0.930 (0.109) ** | −1.146, −0.714 |

| Grade (ref = 9th and 10th grade) | −0.376 (0.164) * | −0.701,−0.051 | |

| Gender (ref = male) | −0.008 (0.190) | −0.385, 0.369 | |

| Location (ref = urban) | |||

| Rural MO | 0.100 (0.181) | −0.260, 0.460 | |

| Rural Central Valley | 0.471 (0.180) * | 0.113, 0.830 | |

| Health Behaviors | |||

| Physical Activity | Pre-test score | −0.685 (0.082) ** | −0.847, −0.522 |

| Grade (ref = 9th and 10th grade) | −0.001 (0.366) | −0.728, 0.726 | |

| Gender (ref = male) | −0.070 (0.428) | −0.919, 0.779 | |

| Location (ref = urban) | |||

| Rural MO | 0.865 (0.403) * | 0.064, 1.666 | |

| Rural Central Valley | 0.587 (0.405) | −0.218, 1.391 | |

| Consumption of fruits and vegetables | Pre-test score | −0.612 (0.093) ** | −0.796, −0.427 |

| Grade (ref = 9th and 10th grade) | 0.049 (.199) | −0.347, 0.445 | |

| Gender (ref = male) | 0.083 (.230) | −0.373, 0.540 | |

| Location (ref = urban) | |||

| Rural MO | −0.131 (0.228) | −0.584, 0.322 | |

| Rural Central Valley | −0.097 (0.223) | −0.540, 0.346 | |

| Consumption of sugary drinks | Pre-test score | −0.588 (.073) ** | −0.733, −0.442 |

| Grade (ref = 9th and 10th grade) | −0.069 (0.192) | −0.449, 0.311 | |

| Gender (ref = male) | −0.235 (0.220) | −0.673, 0.202 | |

| Location (ref = urban) | |||

| Rural MO | 0.550 (0.211) | 0.130, 0.970 | |

| Rural Central Valley | 0.564 (0.213) | 0.141, 0.988 | |

| Consumption of sugary foods | Pre-test score | −0.676 (0.082) ** | −0.839, −0.512 |

| Grade (ref = 9th and 10th grade) | 0.022 (0.209) | −0.394, 0.438 | |

| Gender (ref = male) | 0.371 (0.242) | −0.109, 0.851 | |

| Location (ref = urban) | |||

| Rural MO | 0.470 (0.231) | 0.012, 0.929 | |

| Rural Central Valley | 0.626 (0.233) | 0.164, 1.088 | |

| Stress Reduction | Pre-test score | 0.722 (0.127) ** | −0.975,−0.469 |

| Grade (ref = 9th and 10th grade) | 0.220 (0.244) | −0.264, 0.704 | |

| Gender (ref = male) | 0.215 (0.287) | −0.354, 0.784 | |

| Location (ref = urban) | |||

| Rural MO | −0.455 (0.284) | −1.019, 0.108 | |

| Rural Central Valley | −0.015 (0.276) | −0.563, 0.534 | |

| Youth Assets | |||

| Psychosocial Assets | |||

| Youth Resilience (Combined) | Pre-test score | −0.461 (0.090) ** | −0.639, −0.282 |

| (Self-efficacy and problem solving) | Grade (ref = 9th and 10th grade) | −0.036 (0.747) | −1.519, 1.448 |

| Gender (ref = male) | 0.319 (0.840) | −1.350, 1.988 | |

| Location (ref = urban) | |||

| Rural MO | 0.496 (0.803) | −1.097, 2.090 | |

| Rural Central Valley | 1.889 (0.808) * | 0.284, 3.494 | |

| Self-Esteem | Pre-test score | −0.250 (0.073) ** | −0.395, −0.104 |

| Grade (ref = 9th and 10th grade) | 0.539 (0.785) | −1.020, 2.099 | |

| Gender (ref = male) | 0.629 (0.903) | −1.163, 2.421 | |

| Location (ref = urban) | |||

| Rural MO | 0.970 (0.862) | −0.742, 2.682 | |

| Rural Central Valley | 1.440 (0.865) | −0.277, 3.157 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gefter, L.; Morioka-Douglas, N.; Srivastava, A.; Jiang, C.A.; Patil, S.J.; Rodriguez, E. Remote Implementation of a School-Based Health Promotion and Health Coaching Program in Low-Income Urban and Rural Sites: Program Impact during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1044. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021044

Gefter L, Morioka-Douglas N, Srivastava A, Jiang CA, Patil SJ, Rodriguez E. Remote Implementation of a School-Based Health Promotion and Health Coaching Program in Low-Income Urban and Rural Sites: Program Impact during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):1044. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021044

Chicago/Turabian StyleGefter, Liana, Nancy Morioka-Douglas, Ashini Srivastava, Can Angela Jiang, Sonal J. Patil, and Eunice Rodriguez. 2023. "Remote Implementation of a School-Based Health Promotion and Health Coaching Program in Low-Income Urban and Rural Sites: Program Impact during the COVID-19 Pandemic" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 2: 1044. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021044

APA StyleGefter, L., Morioka-Douglas, N., Srivastava, A., Jiang, C. A., Patil, S. J., & Rodriguez, E. (2023). Remote Implementation of a School-Based Health Promotion and Health Coaching Program in Low-Income Urban and Rural Sites: Program Impact during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1044. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021044