My Journey: Development and Practice-Based Evidence of a Culturally Attuned Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program for Native Youth

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Pregnancy Risk Behaviors among Native American Youth

1.2. Practice-Based Evidence

Culture Cube

1.3. Formative Research

1.4. Development of My Journey

1.4.1. Utilization of Formative Data

1.4.2. Core Concepts of My Journey

- ∙

- Medicine wheel (balance of body, mind, emotion, and spirit)

- ∙

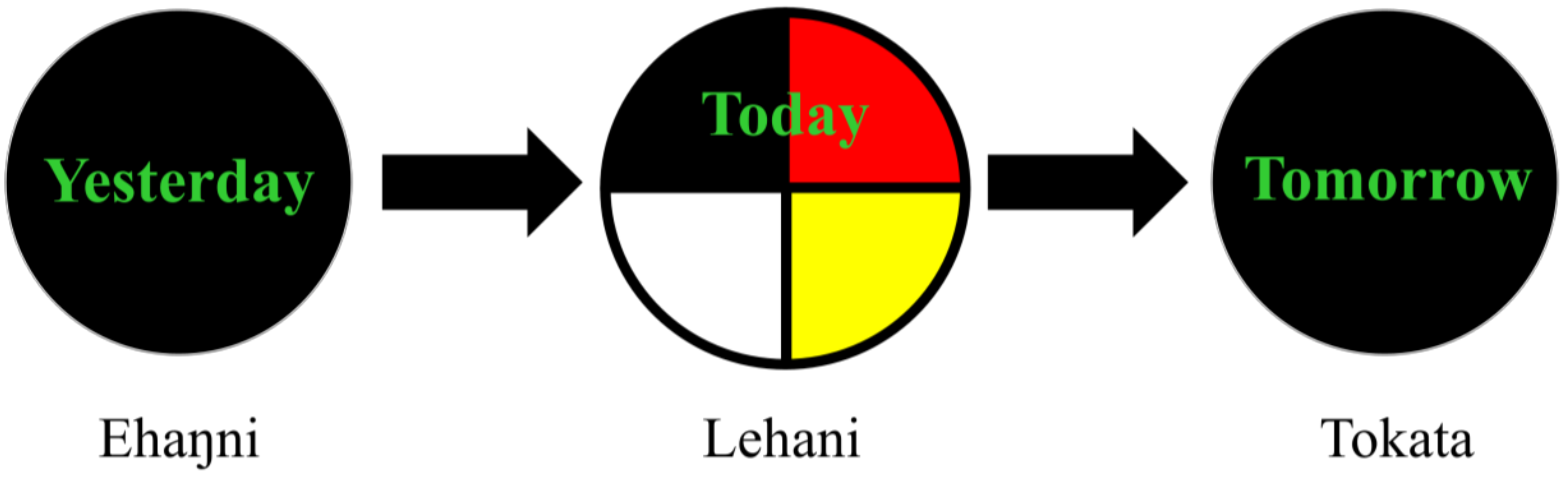

- Chain Reaction Model (yesterday, today, tomorrow)

- ∙

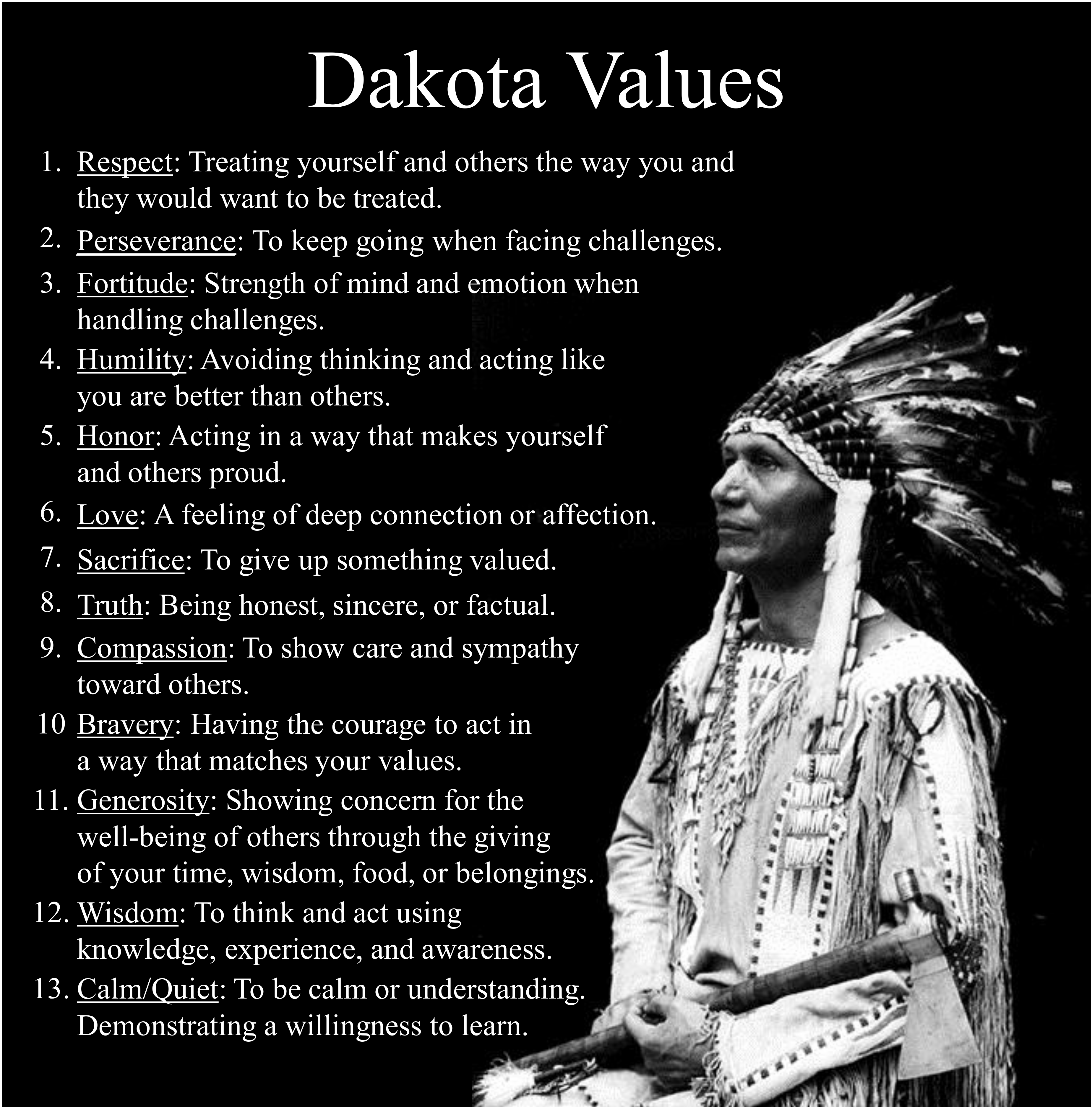

- Traditional Native American values (respect, perseverance, fortitude, humility, honor, love, sacrifice, truth, compassion, bravery, generosity, wisdom, and calm/quiet)

- ∙

- Sexual health (taking personal and sexual responsibility)

- ∙

- Goal setting.

1.5. Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Process Evaluation

- Delivery: Outlined objectives/purpose, was knowledgeable of material, and stated instructions/conclusions clearly and concisely.

- Investment in students: Built student rapport, trust, support, and fostered open communication.

- Demonstrating cultural responsiveness: Respected all cultures, included culturally relevant examples, and corrected assumptions and stereotypes.

- Time management: Stayed on task and was mindful of time constraints.

- Classroom management: Managed group dynamics to keep students on task, focused, and compliant with class values.

- Understanding of key concepts: Demonstrated knowledge of material, aka “Aha!” moments.

- Investment in material: Devoted time, effort, and attention to material.

- Level of engagement: Actively participated in activity and/or discussion.

- Conduct: Compliant with class values.

2.3. Outcome Evaluation

2.3.1. Consent

2.3.2. Outcome Measures

2.3.3. Planned Analyses

2.4. Practice-based Evidence Evaluation

3. Results

3.1. Process Evaluation

- ∙

- “I think the kids learned a lot about STIs and their transmission. The students were very engaged with the STI activity. The students were able to sit and learn about the different types of STIs.”

- ∙

- “The students really liked the discussion on this [birth control trivia]. . . . They also like talking about personal experiences with people they know or what they have read in the media. . . . The students said they learned a lot about pregnancy today.”

3.2. Outcome Evaluation

3.3. Practice-based Evidence Evaluation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Lesson | Student Objective | Purpose | Main Activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yesterday | |||

| 1: Introduction to My Journey | I can explain the purpose of the My Journey program |

|

|

| 2: The Medicine Wheel as a Guiding Symbol | I can describe how the medicine wheel will be used in My Journey |

|

|

| 3. The Medicine Wheel: Body, Mind, Emotion, and Spirit | I can identify and define the four quadrants of the balanced person model |

|

|

| 4. What is Culture? | I can demonstrate how I use the 12 Traditional Values through daily practices |

|

|

| 5. Native American Contributions to Society | I can describe multiple ways that Native Americans have contributed to society throughout history |

|

|

| 6. Chain Reaction | I can describe the three parts of the Chain Reaction |

|

|

| 7. Describing Your Yesterday | I can identify a past event in my own yesterday |

|

|

| Today | |||

| 8. Identity: Who am I? | I can describe how culture influences my identity |

|

|

| 9. Gender and the Media | I can name at least one example of how media portrays a gender stereotype |

|

|

| 10. Adolescence: Changes in the Body, Mind, Emotions, and Spirit | I can explain the changes that happen to my body, mind, emotion, and spirit during puberty/adolescence |

|

|

| 11. The Spirit of Adolescence: Cultural Values | I can explain the changes that happen to my body, mind, emotion, and spirit during puberty/adolescence |

|

|

| 12. Healthy Youth are Balanced | I can describe the difference between making balanced and unbalanced decisions |

|

|

| 13. Balance in Interpersonal Relationships | I can describe the difference between a balanced and out of balanced interpersonal (sexual/dating) relationship |

|

|

| 14. Balanced Decision Making in the Chain Reaction | I can give examples of how a balanced teen would respond in difficult decision points |

|

|

| 15. Balanced Decision-Making: Finding Alternatives | I can relate the Traditional Native American Values to real life situations |

|

|

| 16. Downstream Application of the Chain Reaction | I can identify how balanced and unbalanced decisions impact my ability to achieve my goals |

|

|

| 17. Understanding the Broader Environment | I can explain how the many parts of my broader environment influence my balanced decision-making |

|

|

| 18. Influences on Sexual Values | I can describe how values influence my decision-making about sex |

|

|

| 19. Sexual Values with the Chain Reaction | I can identify verbal and non-verbal steps to making balanced decisions during difficult decision points |

|

|

| 20. Sexual Responsibility: Making Balanced Decisions | I can verbally and non-verbally take steps to make balanced decisions when facing difficult decision points |

|

|

| Tomorrow | |||

| 21. Aiming for My Goals | I can identify how knowing my goals will help guide my balanced decision-making. |

|

|

| 22. Role Models | I can describe how my personal role models influence my balanced decision-making |

|

|

| 23. Reality Check: Teen Pregnancy | I can explain how becoming a teen parent would change my life journey |

|

|

| 24. Reality Check: STIs/STDs | I can list multiple ways to prevent getting an STI/STD |

|

|

| 25. Pregnancy Prevention | I can list multiple ways to prevent pregnancy |

|

|

| 26. Kinship and Social Support | I can describe how kinship and social support influence my balanced decision-making |

|

|

| 27. Connecting with Social Supports | I can describe the importance of a trusted adult and new ways to build social supports |

|

|

| 28. The Path of My Journey | I can describe in detail the core concepts of My Journey |

|

|

References

- Martin, J.A.; Hamilton, B.E.; Osterman, M.J.K.; Driscoll, A.K.; Drake, P. Births: Final data for 2017; National Vital Statistics Reports; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2018; Volume 67. [Google Scholar]

- Boonstra, H.D. What is behind the declines in teen pregnancy rates? Guttmacher Policy Rev. 2014, 17, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes-Alcantara, A.L. Teen Birth Trends: In Brief; Congressional Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kearney, M.S.; Levine, P.B. Why is the teen birth rate in the United States so high and why does it matter? J. Econ. Perspect. 2012, 26, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, J.A.; Hamilton, B.E.; Ventura, S.J.; Osterman, M.J.K.; Matthews, T.J. Births: Final Data for 2011; National Vital Statistics Reports; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2013; Volume 62. [Google Scholar]

- De Ravello, L.; Jones, S.E.; Tulloch, S.; Taylor, M.; Doshi, S. Substance use and sexual risk behaviors among American Indian and Alaska Native high school students. J. Sch. Health 2014, 84, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Surveilance System (YRBSS) Youth Online Data; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, D.J.; A Native Judge‘s Fight for Equity Pt. 1. 2018. Available online: https://powertodecide.org/news/native-judges-fight-for-equity-pt-1 (accessed on 3 December 2018).

- Edwards, S. Among Native American teenagers, sex without contraceptives is common. Fam. Plan. Perspect. 1992, 24, 189–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban Indian Health Institute, Seattle Indian Health Board. Reproductive Health of Urban American Indian and Alaska Native Women: Examining Unintended Pregnancy, Contraception, Sexual History and Behavior, and Non-Voluntary Sexual Intercourse; Urban Indian Health Institute: Seattle, WA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, J.D.; McMahon, T.R.; Griese, E.R.; Kenyon, D.B. Understanding gender roles in teen pregnancy prevention among American Indian youth. Am. J. Health Behav. 2014, 38, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, R.D.; Bigelow, D.A. A constructive Indian Country response to the evidence-based program mandate. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2011, 43, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lugo-Gil, J.; Lee, A.; Vohra, D.; Harding, J.; Ochoa, L.; Goesling, B. Updated Findings from the HHS Teen Pregnancy Prevention Evidence Review: August 2015 through October 2016; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- Kaufman, C.E.; Schwinn, T.M.; Black, K.; Keane, E.M.; Big Crow, C.K.; Shangreau, C.; Tuitt, N.R.; Arthur-Asmah, R.; Morse, B. Impacting precursors to sexual behavior among young American Indian adolescents of the Northern Plains: A cluster randomized controlled trial. J. Early Adolesc. 2018, 38, 988–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, C.E.; Schwinn, T.M.; Black, K.; Keane, E.M.; Big Crow, C.K. The promise of technology to advance rigorous evaluation of adolescent pregnancy prevention programs in American Indian and Alaska Native tribal communities. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, S18–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, E.H.; Walker, R.D. Best Practices in Behavioral Health Services for American Indians and Alaska Natives; One Sky National Resource Centre for American Indian and Alaska Native Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment Services: Portland, OR, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Abe, J.; Grills, C.; Ghavami, N.; Xiong, G.; Davis, C.; Johnson, C. Making the invisible visible: Identifying and articulating culture in practice-based evidence. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2018, 62, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, K.L.; Garney, W.R.; Hays, C.N.; Nelson, J.L.; Farmer, J.L.; McLeroy, K.R. Encouraging innovation in teen pregnancy prevention programs. Creat. Educ. 2017, 8, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacs, M.R.; Huang, L.N.; Hernandez, M.; Echo-Hawk, H. The Road to Evidence: The Intersection of Evidence-Based Practices and Cultural Competence in Children’s Mental Health; National Alliance of Multi-Ethnic Behavioral Health Associations: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, T.L.; Friesen, B.J.; Jivanjee, P.; Gowen, L.K.; Bandurraga, A.; Matthew, C.; Maher, N. Defining youth success using culturally appropriate community-based participatory research methods. Best Pract. Ment. Health 2011, 7, 94–114. [Google Scholar]

- Friesen, B.J.; Cross, T.L.; Jivanjee, P.R.; Gowen, L.K.; Bandurraga, A.; Bastomski, S.; Matthew, C.; Maher, N.J. More than a nice thing to do: A practice-based evidence approach to outcome evaluation in Native youth and Family Programs. In Handbook of Race and Development in Mental Health; Chang, E.C., Downey, C.A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 87–106. [Google Scholar]

- Kratochwill, T.R.; Hoagwood, K.E.; Kazak, A.E.; Weisz, J.R.; Hood, K.; Vargas, L.A.; Banez, G.A. Practice-based evidence for children and adolescents: Advancing the research agenda in schools. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 41, 215–235. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, S.; Whitener, R.; Trupin, E.; Migliarini, N. American Indian perspectives on evidence-based practice implementation: Results from a statewide tribal mental health gathering. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 42, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh-Buhi, M.L. ‘Please don’t just hang a feather on a program or put a medicine wheel on your logo and think ‘oh well, this will work’’: Theoretical perspectives of American Indian and Alaska native substance abuse prevention programs. Fam. Community Health J. Health Promot. Maint. 2017, 40, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammerman, A.; Smith, T.W.; Calancie, L. Practice-based evidence in public health: Improving reach, relevance, and results. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberman, R.; Zubritsky, C.; Martinez, K.; Massey, O.; Fisher, S.; Kramer, T.; Koch, R.; Obrochta, C. Issue Brief: Using Practice-Based Evidence to Complement Evidence-Based Practice in Children’s Mental Health; ICF Macro, Outcomes Roundtable for Children and Families: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lucero, E. From tradition to evidence: Decolonization of the evidence-based practice system. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2011, 43, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Israel, B.A.; Schulz, A.J.; Parker, E.A.; Becker, A.B.; Allen, A.J.; Guzman, R.J. Critical issues in developing and following community-based participatory research principles. In Community-Based Participatory Research for Health; Minkler, M., Wallerstein, N., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 53–76. [Google Scholar]

- Sahota, P.C. Community-Based Participatory Research in American Indian and Alaska Native Communities; National Congress of American Indians Policy Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, L.R.; Rosa, C.; Forcehimes, A.; Donovan, D.M. Research partnerships between academic institutions and American Indian and Alaska Native tribes and organizations: Effective strategies and lessons learned in a multisite CTN study. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2011, 37, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, T.R.; Hanson, J.D.; Griese, E.R.; Kenyon, D.B. Teen pregnancy prevention program recommendations from urban and reservation Northern Plains American Indian community members. Am. J. Sex. Educ. 2015, 10, 218–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indian Health Service; Health Promotion Disease Prevention Initiative; University of New Mexico Prevention Research Center. Physical Activity Kit (PAK): Staying on the Active Path in Native Communities. A Lifespan Approach. 2018. Available online: https://prc.unm.edu/educational-materials/guides.html (accessed on 13 January 2018).

- Lane, P., Jr.; Bopp, J.; Bopp, M.; Brown, L. The Sacred Tree, 4th ed.; Lotus Press: Twin Lakes, WI, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, T.L. The Relational Worldview and Child Well-Being; Center for Advanced Studies in Child Welfare, University of Minnesota: Saint Paul, MN, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, T.L. Understanding family resiliency from a relational world view. In Resiliency in Native American and Immigrant Families; McCubbin, H.I., Thompson, E.A., Thompson, A.I., Fromer, J.E., Eds.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998; pp. 143–157. [Google Scholar]

- Friesen, B.; Cross, T.; Jivanjee, P.; Thirstrup, A.; Bandurraga, A.; Gowen, L.; Rountree, J. Meeting the transition needs of urban American Indian/Alaska Native youth through culturally based services. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 42, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, D.R.; Limb, G.E.; Cross, T.L. Moving from colonization toward balance and harmony: A Native American perspective on wellness. Soc. Work 2009, 54, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, S.L.; International Office, Albuquerque, NM, USA. National Indian Youth Leadership Project. Personal communication, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mincemoyer, C.C.; Perkins, D.F. Assessing decision-making skills of youth. Forum Fam. Consum. Issues 2003, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney, J. The Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure: A new scale for use with adolescents and young adults from diverse groups. J. Adolesc. Res. 1992, 7, 156–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnick, M.D.; Bearman, P.S.; Blum, R.W.; Bauman, K.E.; Harris, K.M.; Jones, J.; Tabor, J.; Beuhring, T.; Sieving, R.E.; Shew, M.; et al. Protecting adolescents from harm: Findings from the national longitudinal study on adolescent health. J. Am. Med Assoc. 1997, 278, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, K.K.; Kirby, D.B.; Marín, B.V.; Gómez, C.A. Draw the Line/Respect the Line: A randomized trial of a middle school intervention to reduce sexual risk behaviors. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 843–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dippel, E.; Hanson, J.; McMahon, T.; Griese, E.; Kenyon, D. Applying the theory of reasoned action to understanding teen pregnancy with American Indian communities. Matern. Child Health J. 2017, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griese, E.R.; Kenyon, D.B.; McMahon, T.R. Identifying sexual health protective factors among American Indian youth: An ecological approach utilizing multiple perspectives. Am. Indian Alsk. Nativ. Ment. Health Res. 2016, 23, 16–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, K.; Tom, N. Evaluation of a substance abuse, HIV and hepatitis Prevention initiative for urban Native Americans: The Native Voices Program. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2011, 43, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasper, G.; Clohesy, S. Intentional Innovation: How Getting More Systemic about Innovation Could Improve Philanthropy and Increase Social Impact; W.K. Kellogg Foundation: Battle Creek, MI, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

| Topics | Mean | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Facilitation Observations | |||

| · Delivery | 4.11 | 0.82 | 2.40–5 |

| · Investment in students | 4.24 | 0.74 | 2.00–5 |

| · Cultural responsiveness | 4.33 | 0.63 | 2.00–5 |

| · Time management | 3.94 | 0.85 | 3.00–5 |

| · Classroom management | 4.14 | 0.71 | 2.50–5 |

| Student Observations | |||

| · Understanding of concepts | 3.84 | 0.66 | 2.25–5 |

| · Investment in material | 3.90 | 0.68 | 2.00–5 |

| · Level of engagement | 3.86 | 0.76 | 2.00–5 |

| · Conduct | 3.73 | 0.74 | 2.00–5 |

| Scale | Possible Range | Cronbach α Pre/Post | Pretest Mean (SD) | Posttest Mean (SD) | Change Mean (SE – Pre/Post) | Paired t-Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decision-making skills | 1–4 | 0.82/0.87 | 2.54 (0.56) | 2.63 (0.63) | 0.09 (0.09/0.10) | −0.94 |

| Ethnic identity | 1–4 | 0.86/0.94 | 3.38 (0.41) | 3.34 (0.55) | −0.04 (0.06/0.08) | −0.15 |

| Affirmation belonging subscale | 1–4 | 0.89/0.94 | 3.49 (0.47) | 3.45 (0.56) | −0.04 (0.07/0.09) | −0.13 |

| Exploration subscale | 1–4 | 0.70/0.84 | 3.22 (0.50) | 3.20 (0.60) | −0.02 (0.08/0.09) | −0.17 |

| Prosocial connectedness | 1–4 | 0.85/0.78 | 3.06 (0.53) | 3.06 (0.48) | 0 (0.08/0.07) | −0.07 |

| Reasons for not having sex | 1–4 | 0.84/0.80 | 3.54 (0.59) | 3.59 (0.51) | 0.05 (0.09/0.08) | −0.67 |

| Reasons for having sex | 1–4 | 0.88/0.90 | 1.39 (0.49) | 1.34 (0.53) | −0.05 (0.08/0.08) | 1.35 |

| Sex refusal self-efficacy | 1–4 | 0.79/0.90 | 3.47 (0.49) | 3.69 (0.50) | 0.22 (0.08/0.08) | −3.57 * |

| The Observable | |

|---|---|

| Project: What is the activity or the community-defined practice/intervention? |

Community suggestions for a teen pregnancy prevention program, include (in order of the frequency each was mentioned) [31]:

|

| Persons: Who will be involved in delivering and participating in My Journey, and what are they doing? |

|

| Place: Where does My Journey take place in terms of the organizational and/or community setting and geographic location and why is this important? |

|

| The Invisible | |

| Culture: How does My Journey reflect the cultural values, practices, and beliefs of NA communities? |

|

| Causes: What are the problems the project is trying to address? How did it start and why? How are causes understood in (a) a historical context, (b) through the lens of the community’s values, and (c) things that concern or bother the community? | Native Americans experience higher teen pregnancy rates compared to other racial/ethnic groups. Community perceptions on the context and causes of this are varied [11,43].

|

| Changes: From our cultural perspective, what are the desired outcomes of My Journey for our community? We will see more of … and less of … | My Journey encourages healthy decision-making, and will ideally lead to the following outcomes, above and beyond a reduction in teen pregnancy, outlined by the community [11,31,43,44]:

|

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kenyon, D.B.; McMahon, T.R.; Simonson, A.; Green-Maximo, C.; Schwab, A.; Huff, M.; Sieving, R.E. My Journey: Development and Practice-Based Evidence of a Culturally Attuned Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program for Native Youth. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 470. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030470

Kenyon DB, McMahon TR, Simonson A, Green-Maximo C, Schwab A, Huff M, Sieving RE. My Journey: Development and Practice-Based Evidence of a Culturally Attuned Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program for Native Youth. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(3):470. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030470

Chicago/Turabian StyleKenyon, DenYelle Baete, Tracey R. McMahon, Anna Simonson, Char Green-Maximo, Ashley Schwab, Melissa Huff, and Renee E. Sieving. 2019. "My Journey: Development and Practice-Based Evidence of a Culturally Attuned Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program for Native Youth" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 3: 470. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030470

APA StyleKenyon, D. B., McMahon, T. R., Simonson, A., Green-Maximo, C., Schwab, A., Huff, M., & Sieving, R. E. (2019). My Journey: Development and Practice-Based Evidence of a Culturally Attuned Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program for Native Youth. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(3), 470. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030470