Designing and Evaluating a Digital Family Health History Tool for Spanish Speakers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

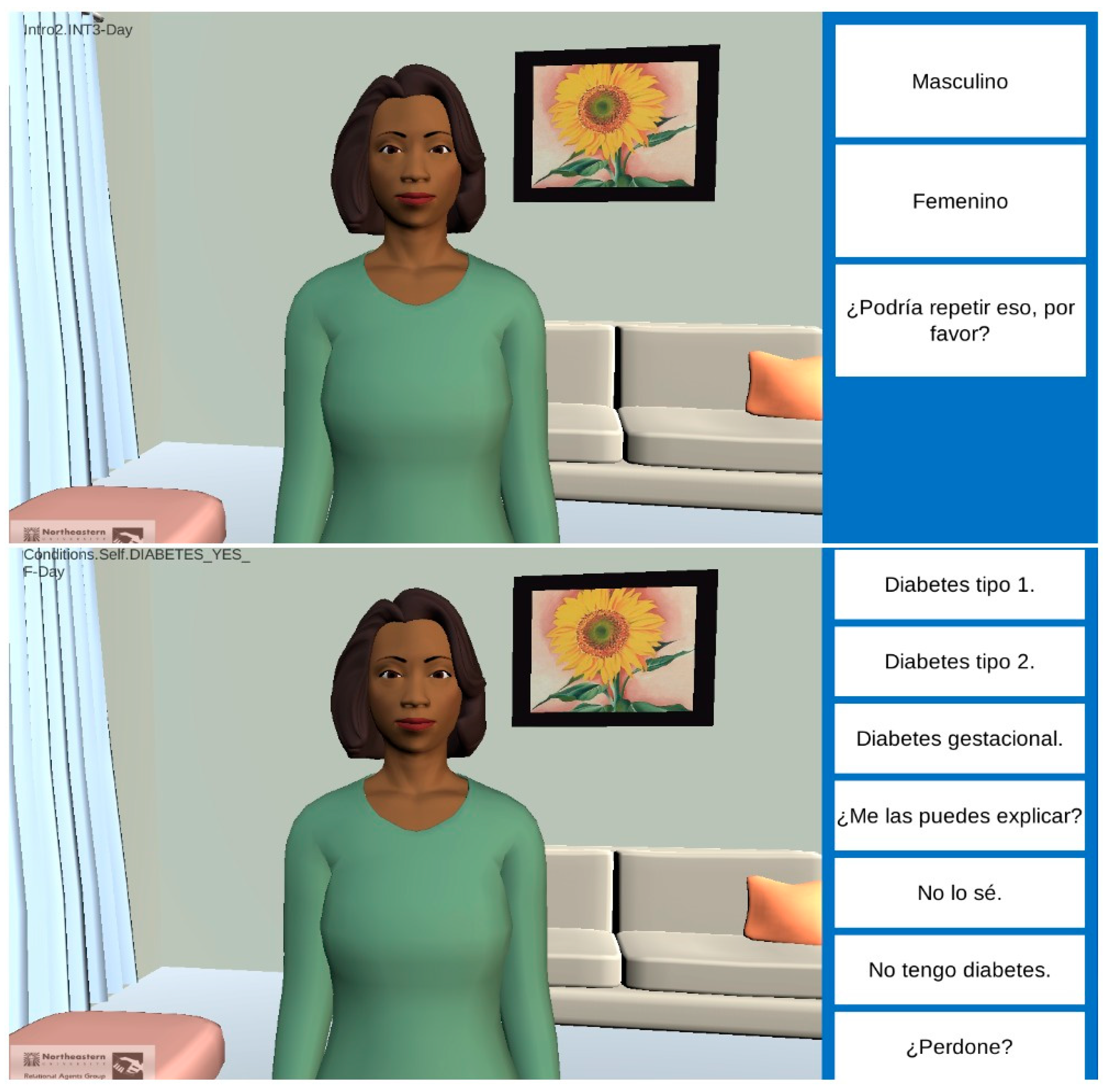

2.1. VICKY Program—System Architecture

2.2. Adaptation and Refinement for Spanish Speakers

2.3. Study Procedures

2.4. Study Measures

2.5. Data Analysis

2.5.1. Demographics and Acceptability Rating Scales

2.5.2. Agreement between Pedigrees

2.5.3. Qualitative Data

3. Results

3.1. Tool Refinement and Initial Comparisons with English Language Tool

3.2. Interviews

3.2.1. Demographics

3.2.2. Agreement between Spanish VICKY and Genetic Counselor

Agreement—Family Members Identified

Agreement—Conditions Identified

3.2.3. Acceptability and Usability of Spanish VICKY

Likeability

In its virtual reality [VICKY] is someone who has many human characteristics like us, and the way [she] communicates is very simple. (Female, age 35–44, possible limited literacy, uses computer regularly).

I liked that VICKY had the sensitivity to also understand that, that when she asked a question that could be somewhat uncomfortable, like the death of a relative, she was sensitive in that aspect. So it was an interesting experience that an impersonal electronic system can be almost real. (Male, age 65 +, limited literacy, computer expert)

Comfort Level and Trust

[One] does not have to be scared or anything like that … there’s nobody looking at you or anything like that, it’s a computer person. It’s like talking to nobody, but they’re listening to you … I wanted to talk without feeling like someone is watching me … I felt comfortable. (Male, age 25–34, limited literacy, uses computer regularly)

I liked it because it opened my mind … because it was difficult for me to start communicating with my doctor, right? And this I liked, I do not know, it made me feel open even about myself, to talk about my health. (Female, age 45–54, limited literacy, tried computer a few times)

[I trust] a lot, it seems to me that it is something that will not come out of there and that is something confidential, and that remains on the computer and nobody else knows it. Nobody else is going to say it. (Female, age 35–44, possible limited literacy, uses computer regularly)

Preference for Gender and Language

Completion Time

A little slow. I feel that it took much longer than it should. (Female, age 35–44, possible limited literacy, uses computer regularly)

Interface Improvements and Customization

Without touching the screen but from voice to voice, like that. (Female, age 45–54, adequate literacy, uses computer regularly)

I would like you to give me information about what I can do about a problem within my family … (Male, age 25–34, limited literacy, tried computer a few times)

Maybe because Latinos talk with their hands, maybe yes, if they use their hands a little when they speak, because Latinos … express themselves a lot when they talk with their hands, I do not know, move them. (Female, age 35–44, possible limited literacy, tried a computer a few times)

Yes, very serious. It’s better if she puts on a smile or something there. (Male, age 25–34, limited literacy, uses computer regularly)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guttmacher, A.E.; Collins, F.S.; Carmona, R.H. The family history—more important than ever. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 2333–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyeritz, R.E. The Family History: The first genetic test, and still useful after all those years? Genet. Med. 2012, 14, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdez, R.; Yoon, P.W.; Qureshi, N.; Green, R.F.; Khoury, M.J. Family history in public health practice: A genomic tool for disease prevention and health promotion. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2010, 31, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, S.M.; Rubinstein, W.S.; Wang, C.; Yoon, P.W.; Acheson, L.S.; Rothrock, N.; Starzyk, E.J.; Beaumont, J.L.; Galliher, J.M.; Ruffin, M.T.; et al. Familial risk for common diseases in primary care: The Family Healthware Impact Trial. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 36, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, E.C.; Burke, W.; Heaton, C.J.; Haga, S.; Pinsky, L.; Short, M.P.; Acheson, L. Reconsidering the family history in primary care. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2004, 19, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanni, M.A.; Murray, M.F. The application of computer-based tools in obtaining the genetic family history. Curr. Protoc. Hum. Genet. 2010, 66, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanetzke, E.E.; Lynch, J.; Prows, C.A.; Siegel, R.M.; Myers, M.F. Perceived utility of parent-generated family health history as a health promotion tool in pediatric practice. Clin. Pediatr. 2011, 50, 720–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, M.E.; Stockdale, A.; Flynn, B.S. Interviews with primary care physicians regarding taking and interpreting the cancer family history. Fam. Pract. 2008, 25, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, B.M.; Wiley, K.; Pflieger, L.; Achiangia, R.; Baker, K.; Hughes-Halbert, C.; Morrison, H.; Schiffman, J.; Doerr, M. Review and comparison of electronic patient-facing family health history tools. J. Genet. Couns. 2018, 27, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arar, N.; Delgado, E.; Lee, S.; Abboud, H.E. Improving learning about familial risks using a multicomponent approach: The GRACE program. Pers. Med. 2013, 10, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arar, N.; Seo, J.; Abboud, H.E.; Parchman, M.; Noel, P. Veterans’ experience in using the online Surgeon General’s family health history tool. Pers. Med. 2011, 8, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, K.A.; Lynch, J.; Prows, C.A.; Siegel, R.M.; Myers, M.F. Mothers’ perceptions of family health history and an online, parent-generated family health history tool. Clin. Pediatr. 2013, 52, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, J.P.; Baugh, C.; Cornett, S.; Hood, B.; Prows, C.A.; Ryan, N.; Warren, N.S.; Au, M.G.; Brown, M.K.; Glandorf, K.; et al. A family history demonstration project among women in an urban Appalachian community. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2009, 3, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Gallo, R.E.; Fleisher, L.; Miller, S.M. Literacy assessment of family health history tools for public health prevention. Public Health Genom. 2011, 14, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bickmore, T.W.; Paasche-Orlow, M.K. The role of information technology in health literacy research. J. Health Commun. 2012, 17 (Suppl. 3), 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veinot, T.C.; Mitchell, H.; Ancker, J.S. Good intentions are not enough: How informatics interventions can worsen inequality. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2018, 25, 1080–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facio, F.M.; Feero, W.G.; Linn, A.; Oden, N.; Manickam, K.; Biesecker, L.G. Validation of My Family Health Portrait for six common heritable conditions. Genet. Med. 2010, 12, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Bickmore, T.; Bowen, D.J.; Norkunas, T.; Campion, M.; Cabral, H.; Winter, M.; Paasche-Orlow, M. Acceptability and feasibility of a virtual counselor (VICKY) to collect family health histories. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 822–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponathil, A.; Ozkan, N.F.; Bertrand, J.; Welch, B.; Madathil, K.C. New approaches to collecting family health history—A preliminary study investigating the efficacy of conversational systems to collect family health history. Proc. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. Annu. Meet. 2018, 62, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Census Bureau. Profile America Facts for Features: CB19-07: Hispanic Heritage Month 2019. Available online: https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/newsroom/facts-for-features/2019/hispan ic-heritage-month.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2019).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health of Hispanic or Latino Population. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/hispanic-health.htm (accessed on 3 October 2019).

- Institute of Medicine. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care; Smedley, B.D., Stith, A.Y., Nelson, A.R., Eds.; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Heron, M. Deaths: Leading Causes for 2017; National Vital Statistics Reports; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2019.

- United States Census Bureau. 2017 American Community Survey Single-Year Estimates. 2019. Available online: https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml (accessed on 3 October 2019).

- Grosz, B.J.; Sidner, C.L. Attention, intention, and the structure of discourse. Comput. Linguist. 1986, 12, 175–204. [Google Scholar]

- Reiter, E.; Dale, R. Building Natural Language Generation Systems; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; ISBN 0-521-62036-8. [Google Scholar]

- Cassell, J.; Vilhjalmsson, H.H.; Bickmore, T.W. BEAT: The Behavior Expression Animation Toolkit. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the SIGGRAPH, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 5–9 August 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bickmore, T.W.; Trinh, H.; Olafsson, S.; O’Leary, T.K.; Asadi, R.; Rickles, N.M.; Cruz, R. Patient and consumer safety risks when using conversational assistants for medical information: An observational study of Siri, Alexa, and Google Assistant. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e11510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravo, M.; Canino, G.J.; Rubio-Stipec, M.; Woodbury-Farina, M. A cross-cultural adaptation of a psychiatric epidemiologic instrument: The diagnostic interview schedule’s adaptation in Puerto Rico. Cult. Med. Psychiatry 1991, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canino, G.; Bravo, M. The adaptation and testing of diagnostic and outcome measures for cross-cultural research. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 1994, 6, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, D.E.; Gerena, M.; Canino, G.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Febo, V.; Magana, C.; Soto, J.; Eisen, S.V. Translation and cultural adaptation of a mental health outcome measure: The BASIS-R(c). Cult. Med. Psychiatry 2007, 31, 25–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaherty, J.A.; Gaviria, F.M.; Pathak, D.; Mitchell, T.; Wintrob, R.; Richman, J.A.; Birz, S. Developing instruments for cross-cultural psychiatric research. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1988, 176, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila, R. Full metal jacket: Versiones en español y en latino. Rev. Filol. Univ. Laguna 2018, 36, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Izquierdo, I. El español neutron y la traducción dfel los lenguajes de especialidad. Sendebar 2006, 17, 149–167. [Google Scholar]

- Cereproc. Available online: https://www.cereproc.com/ (accessed on 9 January 2019).

- Ávila, R. La pronunciación en la radio de 20 países hispánicos: Comentarios deportivos espontáneos. Nueva Rev. Filol. Hispánica 2016, 64, 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Weiss, B.D.; Mays, M.Z.; Martz, W.; Castro, K.M.; DeWalt, D.A.; Pignone, M.P.; Mockbee, J.; Hale, F.A. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: The newest vital sign. Ann. Fam. Med. 2005, 3, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, L.H.; Puleo, E.; Bennett, G.G.; Emmons, K.M. Exploring social contextual correlates of computer ownership and frequency of use among urban, low-income, public housing adult residents. J. Med. Internet Res. 2007, 9, e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleiss, J.; Levin, B.; Paik, M. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc: New York, NY, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-0-471-52629-2. [Google Scholar]

- King, A.C.; Bickmore, T.W.; Campero, M.I.; Pruitt, L.A.; Yin, J.L. Employing virtual advisors in preventive care for underserved communities: Results from the COMPASS study. J. Health Commun. 2013, 18, 1449–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendu, S.; Boukhechba, M.; Gordon, J.R.; Datta, D.; Molina, E.; Arroyo, G.; Proctor, S.K.; Wells, K.J.; Barnes, L.E. Design of a culturally-informed virtual human for educating Hispanic women about cervical cancer. In Proceedings of the 12th EAI International Conference on Pervasive Computing Technologies for Healthcare (PervasiveHealth ’18), New York, NY, USA, 21–24 May 2018; Volume 2018, pp. 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L., Bickmore, T., Cortes, D.E., Eds.; The impact of linguistic and cultural continuity on persuasion by conversational agents. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Virtual Agents, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 20–22 September 2010; Volume 6356. [Google Scholar]

- Bickmore, T.W.; Pfeifer, L.M.; Byron, D.; Forsythe, S.; Henault, L.E.; Jack, B.W.; Silliman, R.; Paasche-Orlow, M.K. Usability of conversational agents by patients with inadequate health literacy: Evidence from two clinical trials. J. Health Commun. 2010, 15 (Suppl. 2), 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pew Research Center. Mobile Fact Sheet. Available online: https://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/mobile/ (accessed on 27 September 2019).

- Shields, W.C.; Omaki, E.; McDonald, E.M.; Rosenberg, R.; Aitken, M.; Stevens, M.W.; Gielen, A.C. Cell phone and computer use among parents visiting an urban pediatric emergency department. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2018, 34, 878–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, M.; Horrigan, J.B. Smartphones Help Those without Broadband Get Online, But Don’t Necessarily Bridge the Digital Divide. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/10/03/smartphones-help-those-without-broadband-get-online-but-dont-necessarily-bridge-the-digital-divide/ (accessed on 27 September 2019).

- Anderson, M.; Kumar, M. Digital Divide Persists Even as Lower-Income Americans Make Gains in Tech Adoption. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/05/07/digital-divide-persists-even-as-lower-income-americans-make-gains-in-tech-adoption/ (accessed on 27 September 2019).

- Wang, C.; Sen, A.; Plegue, M.; Ruffin, M.T., IV; O’Neill, S.M.; Rubinstein, W.S.; Acheson, L.S. Family Healthware Impact Trial (FHITr) Group; Family Healthware Impact Trial FHITr Group. Impact of family history assessment on communication with family members and health care providers: A report from the Family Healthware Impact Trial (FHITr). Prev. Med. 2015, 77, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W.F.; Ropka, M.E.; Pelletier, S.L.; Barrett, J.R.; Kinzie, M.B.; Harrison, M.B.; Liu, Z.; Miesfeldt, S.; Tucker, A.L.; Worrall, B.B.; et al. Health Heritage ©, a web-based tool for the collection and assessment of family health history: Initial user experience and analytic validity. Public Health Genom. 2010, 13, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gender | N (%) | Country/US Territory of Origin | N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 19 (34%) | Puerto Rico | 20 (35.7%) |

| Female | 37 (66%) | Dominican Republic | 14 (25%) |

| El Salvador | 7 (12.5%) | ||

| Age | Guatemala | 2 (3.6%) | |

| 21–24 | 3 (5.4%) | Honduras | 2 (3.6%) |

| 25–34 | 12 (21.4%) | Ecuador | 1 (1.8%) |

| 35–44 | 11 (19.6%) | Brazil | 1 (1.8%) |

| 45–54 | 10 (17.9%) | Colombia | 1 (1.8%) |

| 55–64 | 13 (23.2%) | Mexico | 8 (14.3%) |

| 65+ | 7 (12.5%) | ||

| Education | Health literacy | ||

| <9th grade | 10 (17.9%) | High likelihood of limited literacy | 12 (21.4%) |

| 9–12th grade, no diploma | 10 (17.9%) | Possibility of limited literacy | 7 (12.5%) |

| High school diploma or equivalent | 15 (26.8%) | Almost always adequate literacy | 37 (66.1%) |

| Some college, no degree | 4 (7.1%) | ||

| Associate degree | 2 (3.6%) | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 9 (16.1%) | ||

| Graduate degree | 3 (5.5%) | ||

| Post graduate degree (doctorate) | 3 (5.5%) | ||

| Income | Computer experience | ||

| $25,000 or less | 27 (48.2%) | Never used one | 13 (23.2%) |

| $25,001–$35,000 | 7 (12.5%) | Tried one a few times | 18 (32.1%) |

| $35,001–$50,000 | 2 (3.6%) | Use one regularly | 20 (35.7%) |

| $50,001–$75,000 | 3 (5.4%) | I’m an expert | 5 (8.9%) |

| No answer | 17 (30.4%) |

| Conditions Identified among First Degree Relatives (Number of Cases per Pedigree) | VICKY (Number of Pedigrees) | Genetic Counselor (Number of Pedigrees) | Distribution of Agreement | Weighted Kappa (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart Problem (including heart attack) | |||||

| 0 | 35 | 33 | Perfect agreement | 41 | 0.6615 (0.5029, 0.8202) |

| 1 | 10 | 16 | Within 1 case | 12 | |

| 2 | 7 | 1 | Within 2 cases | 2 | |

| 3+ | 3 | 5 | Within 3+ cases | 0 | |

| Stroke | |||||

| 0 | 46 | 49 | Perfect agreement | 47 | 0.4695 (0.1677, 0.7712) |

| 1 | 7 | 5 | Within 1 case | 7 | |

| 2 | 2 | 0 | Within 2 cases | 1 | |

| 3+ | 0 | 1 | Within 3+ cases | 0 | |

| Diabetes 1 | |||||

| 0 | 32 | 23 | Perfect agreement | 34 | 0.5911 (0.4295, 0.7527) |

| 1 | 13 | 18 | Within 1 case | 18 | |

| 2 | 5 | 6 | Within 2 cases | 3 | |

| 3+ | 5 | 8 | Within 3+ cases | 0 | |

| Cancer 2 | |||||

| 0 | 49 | 45 | Perfect agreement | 48 | 0.6590 (0.4665, 0.8515) |

| 1 | 4 | 6 | Within 1 case | 7 | |

| 2 | 1 | 4 | Within 2 cases | 0 | |

| 3+ | 1 | 0 | Within 3+ cases | 0 | |

| High Blood Pressure | |||||

| 0 | 20 | 20 | Perfect agreement | 35 | 0.6556 (0.5156, 0.7956) |

| 1 | 17 | 13 | Within 1 case | 17 | |

| 2 | 9 | 12 | Within 2 cases | 3 | |

| 3+ | 9 | 10 | Within 3+ cases | 0 | |

| Likability Area | Illustrative Quote |

|---|---|

| Use of plain language | the clear way [she] asks the questions: very simple and very precise |

| Multiple choice response format | [she] would ask the question and would provide options clearly |

| User friendly | everything was step by step |

| Not feeling pressed for time | VICKY has the time to listen to you and you can take your time to answer the questions, things you do not have with the doctor. |

| Human-like connection | What I liked most about VICKY was that she looked more or less like a person … [VICKY] gave me that feeling that I was talking to a live person. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cerda Diez, M.; E. Cortés, D.; Trevino-Talbot, M.; Bangham, C.; Winter, M.R.; Cabral, H.; Norkunas Cunningham, T.; M. Toledo, D.; J. Bowen, D.; K. Paasche-Orlow, M.; et al. Designing and Evaluating a Digital Family Health History Tool for Spanish Speakers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4979. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16244979

Cerda Diez M, E. Cortés D, Trevino-Talbot M, Bangham C, Winter MR, Cabral H, Norkunas Cunningham T, M. Toledo D, J. Bowen D, K. Paasche-Orlow M, et al. Designing and Evaluating a Digital Family Health History Tool for Spanish Speakers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(24):4979. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16244979

Chicago/Turabian StyleCerda Diez, Maria, Dharma E. Cortés, Michelle Trevino-Talbot, Candice Bangham, Michael R. Winter, Howard Cabral, Tricia Norkunas Cunningham, Diana M. Toledo, Deborah J. Bowen, Michael K. Paasche-Orlow, and et al. 2019. "Designing and Evaluating a Digital Family Health History Tool for Spanish Speakers" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 24: 4979. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16244979

APA StyleCerda Diez, M., E. Cortés, D., Trevino-Talbot, M., Bangham, C., Winter, M. R., Cabral, H., Norkunas Cunningham, T., M. Toledo, D., J. Bowen, D., K. Paasche-Orlow, M., Bickmore, T., & Wang, C. (2019). Designing and Evaluating a Digital Family Health History Tool for Spanish Speakers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(24), 4979. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16244979