The Mediating Effect of Sleep Quality on the Relationship between Emotional and Behavioral Problems and Suicidal Ideation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Ethical Statement

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Emotional and Behavioral Problems

2.3.2. Suicidal Ideation

2.3.3. Sleep Quality

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Associations of Emotional and Behavioral Problems and Sleep Quality with Suicidal Ideation

3.3. Mediating Effects of Sleep Quality

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mcloughlin, A.B.; Gould, M.S.; Malone, K.M. Global trends in teenage suicide: 2003–2014. QJM 2015, 108, 765–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, F.; Chang, Q.; Law, Y.W.; Hong, Q.; Yip, P.S.F. Suicide rates in China, 2004–2014: Comparing data from two sample-based mortality surveillance systems. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cluver, L.; Orkin, M.; Boyes, M.E.; Sherr, L. Child and adolescent suicide attempts, suicidal behavior, and adverse childhood experiences in South Africa: A prospective study. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 57, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Xu, Y.; Huang, G.; Gao, X.; Deng, X.; Luo, M.; Xi, C.; Zhang, W.H.; Lu, C. Association between body weight status and suicidal ideation among Chinese adolescents: The moderating role of the child’s sex. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2019, 54, 823–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, L.; Xia, T.; Reece, C. Social and individual risk factors for suicide ideation among Chinese children and adolescents: A multilevel analysis. Int. J. Psychol. 2018, 53, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, T.R.; Taylor, D.M. Adolescent Suicidality: Who Will Ideate, Who Will Act? Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2005, 35, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhola, P.; Rekha, D.P.; Sathyanarayanan, V.; Daniel, S.; Thomas, T. Self-reported suicidality and its predictors among adolescents from a pre-university college in Bangalore, India. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2014, 7, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.N.; Liu, L.; Wang, L. Prevalence and associated factors of emotional and behavioural problems in Chinese school adolescents: A cross-sectional survey. Child Care Health Dev. 2014, 40, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca-Pedrero, E.; Inchausti, F.; Pérez-Gutiérrez, L.; Aritio Solana, R.; Ortuño-Sierra, J.; Sánchez-García, M.Á.; Lucas-Molina, B.; Domínguez, C.; Foncea, D.; Espinosa, V.; et al. Suicidal ideation in a community-derived sample of Spanish adolescents. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2018, 11, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoval, G.; Mansbach-Kleinfeld, I.; Farbstein, I.; Kanaaneh, R.; Lubin, G.; Apter, A.; Weizman, A.; Zalsman, G. Self versus maternal reports of emotional and behavioral difficulties in suicidal and non-suicidal adolescents: An Israeli nationwide survey. Eur. Psychiatry 2013, 28, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-García, M.D.L.Á.; de Albéniz Pérez, A.; Paino, M.; Fonseca-Pedrero, E. Emotional and behavioral adjustment in a spanish sample of adolescents. Actas Esp. Psiquiatr. 2018, 46, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Quach, J.L.; Nguyen, C.D.; Williams, K.E.; Sciberras, E. Bidirectional Associations Between Child Sleep Problems and Internalizing and Externalizing Difficulties From Preschool to Early Adolescence. JAMA Pediatr. 2018, 172, e174363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, S.S.; Gujar, N.; Hu, P.; Jolesz, F.A.; Walker, M.P. The human emotional brain without sleep—A prefrontal amygdala disconnect. Curr. Biol. 2007, 17, R877–R878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, K.; Allan, S.; Beattie, L.; Bohan, J.; MacMahon, K.; Rasmussen, S. Sleep problem, suicide and self-harm in university students: A systematic review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2019, 44, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Lam, J.; Zhang, J.; Yu, M.; Chan, J.; Chan, C.; Espie, C.; Freeman, D.; Mason, O.; Wing, Y. Can sleep disturbances predict suicide risk in patients with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders? A 8-year naturalistic longitudinal study. Sleep Med. 2015, 16, S45–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelaye, B.; Okeiga, J.; Ayantoye, I.; Berhane, H.Y.; Berhane, Y.; Williams, M.A. Association of suicidal ideation with poor sleep quality among Ethiopian adults. Sleep Breath. 2016, 20, 1319–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkooijen, S.; de Vos, N.; Bakker-Camu, B.J.W.; Branje, S.J.T.; Kahn, R.S.; Ophoff, R.A.; Plevier, C.M.; Boks, M.P.M. Sleep Disturbances, Psychosocial Difficulties, and Health Risk Behavior in 16,781 Dutch Adolescents. Acad. Pediatr. 2018, 18, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R.; Meltzer, H.; Bailey, V. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A pilot study on the validity of the self-report version. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2003, 15, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, K.Y.C.; Luk, E.S.L.; Leung, P.W.L.; Wong, A.S.Y.; Law, L.; Ho, K. Validation of the Chinese version of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire in Hong Kong. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2010, 45, 1179–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Xu, Y.; Deng, J.; Huang, J.; Huang, G.; Gao, X.; Wu, H.; Pan, S.; Zhang, W.H.; Lu, C. Association between nonmedical use of prescription drugs and suicidal behavior among adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2016, 170, 971–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F.; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. Buysse 1989 The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index—A new instrument for assessing sleep in psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.L.; Rohay, J.; Chasens, E.R. Sex Differences in the Psychometric Properties of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. J. Womens Health 2018, 27, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, B.; Li, M.; Wang, K.L.; Lv, J. [Analysis of the reliability and validity of the Chinese version of Pittsburgh sleep quality index among medical college students]. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao 2016, 48, 424–428. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Klonsky, E.D.; May, A.M.; Saffer, B.Y. Suicide, Suicide Attempts, and Suicidal Ideation. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 12, 307–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Wang, W.; Wang, T.; Li, W.; Gong, M.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, W.H.; Lu, C. Association of emotional and behavioral problems with single and multiple suicide attempts among Chinese adolescents: Modulated by academic performance. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 258, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaess, M.; Parzer, P.; Haffner, J.; Steen, R.; Roos, J.; Klett, M.; Brunner, R.; Resch, F. Explaining gender differences in non-fatal suicidal behaviour among adolescents: A population-based study. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.M.; Han, D.H.; Trksak, G.H. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping: An Gender differences in adolescent coping behaviors and suicidal ideation: Findings from a sample of 73,238 adolescents. Anxiety Stress Coping 2014, 27, 439–454. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, J.D.; Huang, X.; Fox, K.R.; Franklin, J.C. Depression and hopelessness as risk factors for suicide ideation, attempts and death: Meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Br. J. Psychiatry 2018, 212, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotenstein, L.S.; Ramos, M.A.; Torre, M.; Segal, J.B.; Peluso, M.J.; Guille, C.; Sen, S.; Mata, D.A. Prevalence of Depression, Depressive Symptoms, and Suicidal Ideation Among Medical Students A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA 2016, 316, 2214–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haw, C.; Saunders, K.; Hawton, K.; Casan, C. Risk factors for suicide in individuals with depression: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 147, 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- De Wilde, E.J.; van de Looij, P.; Goldschmeding, J.; Hoogeveen, C. Self-Report of Suicidal Thoughts and Behavior vs. School Nurse Evaluations in Dutch High-School Students. Crisis 2011, 32, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouvard, M.P.; Encrenaz, G.; Messiah, A.; Fombonne, E. Hyperactivity-inattention symptoms in childhood and suicidal behaviors in adolescence: The Youth Gazel Cohort. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2008, 118, 480–489. [Google Scholar]

- Drolet, M.; Arcand, I.; Ducharme, D.; Leblanc, R. The Sense of School Belonging and Implementation of a Prevention Program: Toward Healthier Interpersonal Relationships Among Early Adolescents. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2013, 30, 535–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Takahashi, M.; Wu, R.; Liu, Z.; Adachi, M.; Saito, M.; Nakamura, K.; Jiang, F. Association between Sleep Disturbances and Emotional/Behavioral Problems in Chinese and Japanese Preschoolers. Behav. Sleep Med. 2019, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sher, L.; Mann, J.J.; Oquendo, M.A. Sleep, psychiatric disorders and suicide. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2013, 47, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drapeau, C.W.; Nadorff, M.R. Suicidality in sleep disorders: Prevalence, impact, and management strategies. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2017, 9, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Guo, F.; Huang, Z.; Jiang, L.; Duan, Q.; Zhang, J. Sleep patterns and their association with depression and behavior problems among Chinese adolescents in different grades. Psych J. 2017, 6, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyk, T.R.; Thompson, R.W.; Nelson, T.D. Daily Bidirectional Relationships between Sleep and Mental Health Symptoms in Youth with Emotional and Behavioral Problems. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2016, 41, 983–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Deng, J.; He, Y.; Deng, X.; Huang, J.; Huang, G.; Gao, X.; Lu, C. Prevalence and correlates of sleep disturbance and depressive symptoms among Chinese adolescents: A cross-sectional survey study. BMJ Open 2014, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcmakin, D.L.; Alfano, C.A. Sleep and anxiety in late childhood and early adolescence. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2015, 28, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.; Hsu, J.; Huang, Y. Sleep Problems in Children with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Current Status of Knowledge and Appropriate Management. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2016, 18, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelaye, B.; Barrios, Y.V.; Zhong, Q.Y.; Rondon, M.B.; Borba, C.P.; Sánchez, S.E.; Henderson, D.C.; Williams, M.A. Association of poor subjective sleep quality with suicidal ideation among pregnant Peruvian women. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2015, 37, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, Y.; Sun, L.; Zhou, C.; Ge, D.; Zhang, L. The association between suicidal ideation and sleep quality in elderly individuals: A cross-sectional study in Shandong, China. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 256, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balazs, J.; Miklosi, M.; Halasz, J.; Horváth, L.O.; Szentiványi, D.; Vida, P. Suicidal risk, psychopathology, and quality of life in a clinical population of adolescents. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, R.; King, T.; Priest, N.; Kavanagh, A. Bullying and mental health and suicidal behaviour among 14- to 15-year-olds in a representative sample of Australian children. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2017, 51, 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Total (%) | Suicidal Ideation | No Suicidal Ideation | χ2/t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, N (%) | 20,475 (100.0) | 3725 (18.2) | 16,750 (81.8) | ||

| Gender | 363.871 | <0.001 | |||

| Male | 10,265 (50.1) | 1341 (36.0) | 8924 (53.3) | ||

| Female | 10,210 (49.9) | 2384 (64.0) | 7826 (46.7) | ||

| Age, mean (SD) | 14.95 (1.78) | 14.86 (1.71) | 14.98 (1.79) | −3.891 | <0.001 |

| SDQ, mean (SD) | |||||

| Total difficulties | 10.58 (5.18) | 14.83 (5.43) | 9.63 (4.62) | 60.133 | <0.001 |

| Emotional symptoms | 2.29 (2.25) | 4.20 (2.55) | 1.87 (1.94) | 62.455 | <0.001 |

| Conduct problems | 1.90 (1.37) | 2.57 (1.58) | 1.75 (1.27) | 33.914 | <0.001 |

| Hyperactivity/inattention | 3.39 (2.14) | 4.78 (2.17) | 3.08 (2.01) | 46.017 | <0.001 |

| Peer relationship problems | 2.99 (1.50) | 3.28 (1.63) | 2.93 (1.46) | 13.409 | <0.001 |

| Prosocial behavior | 7.25 (2.19) | 6.98 (2.14) | 7.31 (2.19) | −8.514 | <0.001 |

| PSQI, mean (SD) | |||||

| Subjective sleep quality | 1.13 (0.72) | 1.44 (0.75) | 1.06 (0.70) | 29.512 | <0.001 |

| Sleep latency | 0.65 (0.80) | 0.95 (0.92) | 0.58 (0.76) | 25.764 | <0.001 |

| Sleep duration | 0.51 (0.72) | 0.74 (0.83) | 0.46 (0.69) | 21.819 | <0.001 |

| Habitual sleep efficiency | 0.21 (0.64) | 0.29 (0.66) | 0.19 (0.55) | 9.361 | <0.001 |

| Sleep disturbances | 0.79 (0.57) | 1.07 (0.60) | 0.72 (0.54) | 34.473 | <0.001 |

| Use of sleeping medication | 0.02 (0.20) | 0.07 (0.38) | 0.01 (0.13) | 15.781 | <0.001 |

| Daytime dysfunction | 1.55 (0.92) | 2.09 (0.81) | 1.43 (0.90) | 41.517 | <0.001 |

| PSQI total score | 4.86 (2.72) | 6.65 (2.87) | 4.46 (2.52) | 46.695 | <0.001 |

| Variable | Suicidal Ideation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | AOR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Total difficulties * | 1.22 (1.21, 1.23) | <0.001 | 1.22 (1.21, 1.23) | <0.001 |

| Emotional symptoms * | 1.54 (1.51, 1.56) | <0.001 | 1.52 (1.50, 1.55) | <0.001 |

| Conduct problems * | 1.49 (1.46, 1.53) | <0.001 | 1.52 (1.49, 1.56) | <0.001 |

| Hyperactivity/inattention * | 1.46 (1.44, 1.49) | <0.001 | 1.47 (1.44, 1.49) | <0.001 |

| Peer relationship problems * | 1.17 (1.14, 1.19) | <0.001 | 1.19 (1.16, 1.22) | <0.001 |

| Prosocial problems * | 0.93 (0.92, 0.95) | <0.001 | 0.91 (0.90, 0.93) | <0.001 |

| Sleep disorders | ||||

| No | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Yes | 4.00 (3.68, 4.35) | <0.001 | 4.17 (3.82, 4.54) | <0.001 |

| Variables | β (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

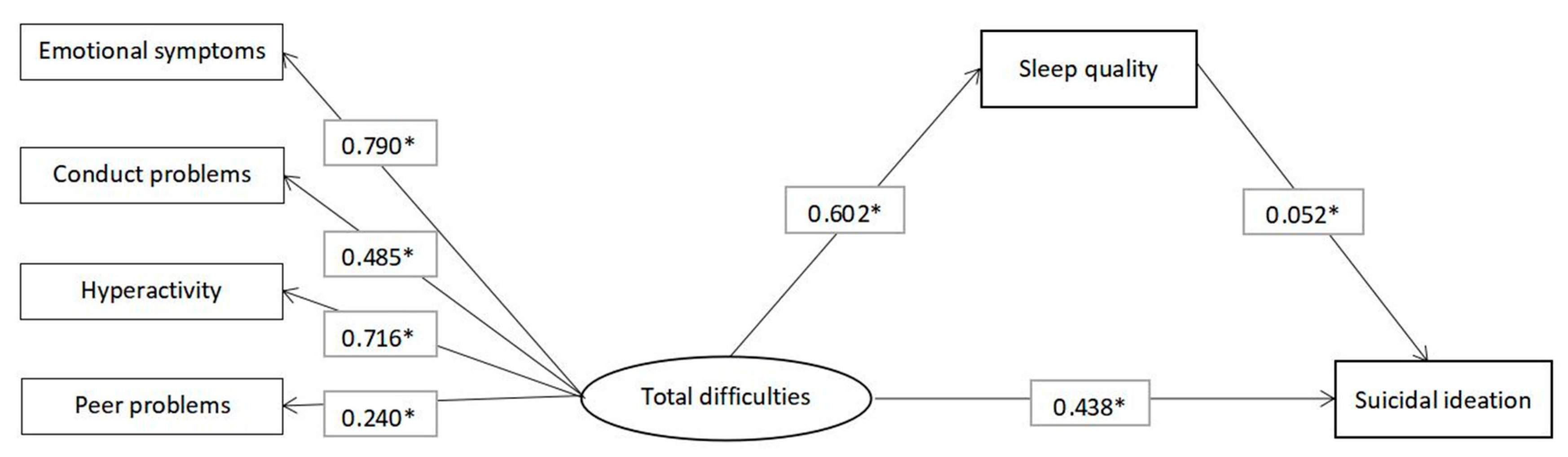

| Path | ||

| Total difficulties → Sleep quality | 0.602 (0.589, 0.615) | <0.001 |

| Sleep quality → Suicidal ideation | 0.052 (0.033, 0.073) | <0.001 |

| Total difficulties → Suicidal ideation | 0.438 (0.416, 0.459) | <0.001 |

| Standardized effect | ||

| Indirect effect | 0.031 (0.020, 0.044) | <0.001 |

| Total effect | 0.469 (0.454, 0.483) | <0.001 |

| Variables | β (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

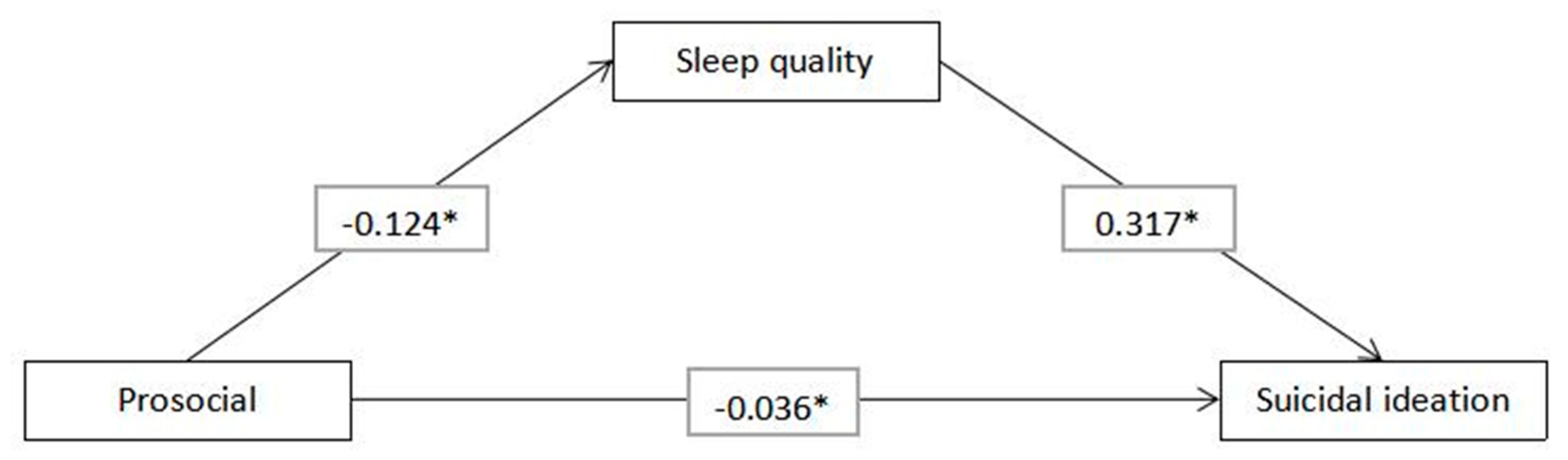

| Path | ||

| Prosocial problems → Sleep quality | −0.124 (−0.139, −0.110) | <0.001 |

| Sleep quality → Suicidal ideation | 0.317 (0.303, 0.331) | <0.001 |

| Prosocial problems → Suicidal ideation | −0.036 (−0.050, −0.024) | <0.001 |

| Standardized effect | ||

| Indirect effect | −0.039 (−0.045, −0.035) | <0.001 |

| Total effect | −0.075 (−0.089, −0.062) | <0.001 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiao, L.; Zhang, S.; Li, W.; Wu, R.; Wang, W.; Wang, T.; Guo, L.; Lu, C. The Mediating Effect of Sleep Quality on the Relationship between Emotional and Behavioral Problems and Suicidal Ideation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4963. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16244963

Xiao L, Zhang S, Li W, Wu R, Wang W, Wang T, Guo L, Lu C. The Mediating Effect of Sleep Quality on the Relationship between Emotional and Behavioral Problems and Suicidal Ideation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(24):4963. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16244963

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Luyao, Sheng Zhang, Wenyan Li, Ruipeng Wu, Wanxin Wang, Tian Wang, Lan Guo, and Ciyong Lu. 2019. "The Mediating Effect of Sleep Quality on the Relationship between Emotional and Behavioral Problems and Suicidal Ideation" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 24: 4963. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16244963

APA StyleXiao, L., Zhang, S., Li, W., Wu, R., Wang, W., Wang, T., Guo, L., & Lu, C. (2019). The Mediating Effect of Sleep Quality on the Relationship between Emotional and Behavioral Problems and Suicidal Ideation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(24), 4963. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16244963