Utilising Digital Health Technology to Support Patient-Healthcare Provider Communication in Fragility Fracture Recovery: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

Research Question

2. Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Intervention

2.1.3. Comparators

2.1.4. Outcomes

2.2. Types of Studies

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Assessment of Methodological Quality

2.6. Data Extraction

2.7. Data Synthesis

3. Results

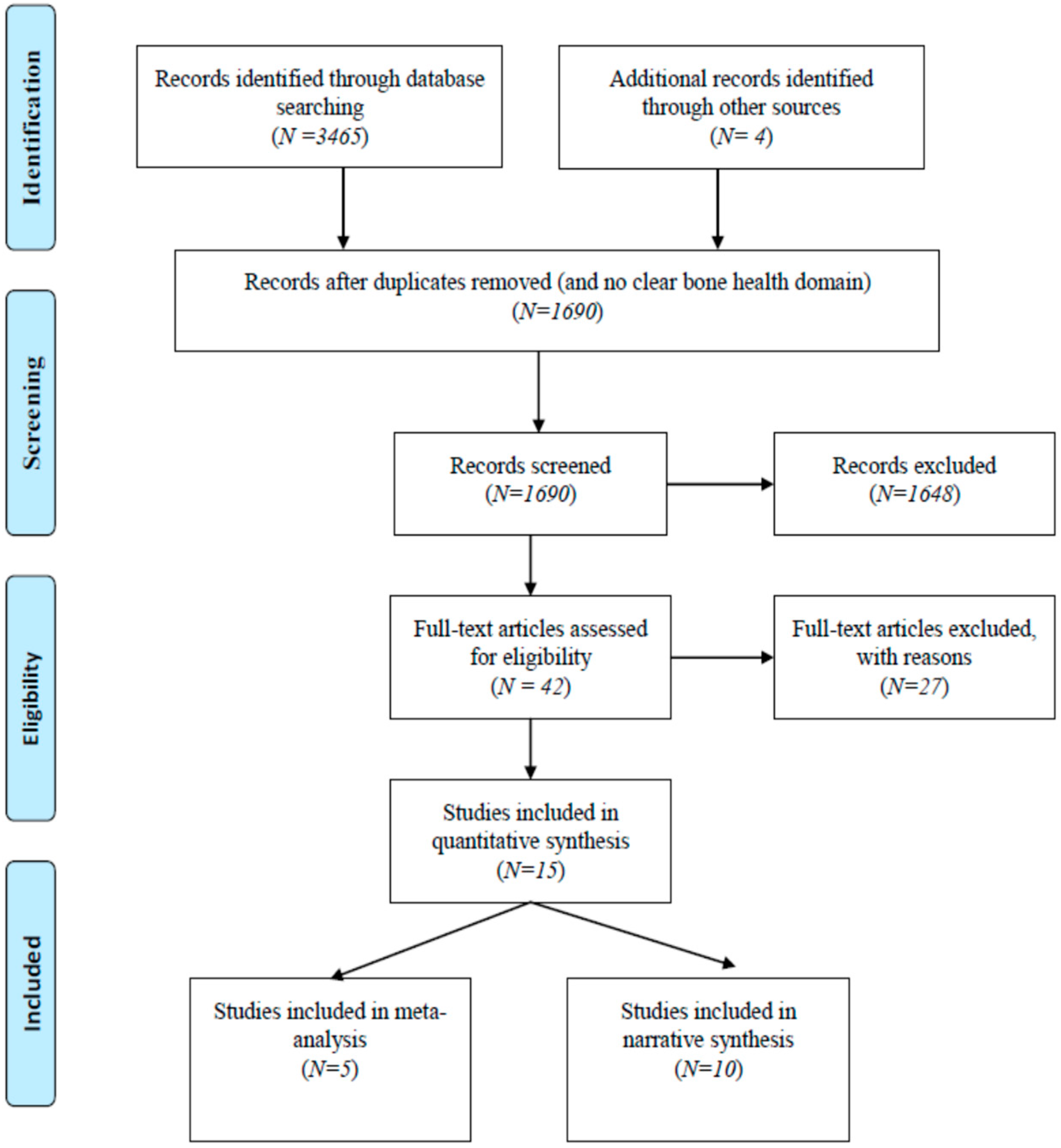

3.1. Study Inclusion

3.2. Methodological Quality

3.3. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.4. Review Findings

3.5. Meta-Analysis

Targeted Patient Communication with Primary Care Physician Support

3.6. Narrative Synthesis

Targeted Patient Communication

3.7. Telemedicine, Personal Health Tracking and Healthcare Provider Decision Support

4. Discussion

4.1. Recommendations for Practice

4.2. Recommendations for Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Osteoporosis: Assessing the Risk of Fragility Fracture; NICE: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-1-4731-2359-5. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, C.; Campion, G.; Melton, L.J., III. Hip fractures in the elderly: A world-wide projection. Osteoporos Int. 1992, 2, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gullberg, B.; Johnell, O.; Kanis, J.A. World-wide projections for hip fracture. Osteoporos Int. 1997, 7, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnell, O.; Kanis, J.A. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence, mortality and disability associated with hip fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2004, 15, 897–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zusman, E.Z.; Dawes, M.G.; Edwards, N.; Ashe, M.C. A systematic review of evidence for older adults’ sedentary behavior and physical activity after hip fracture. Clin. Rehabil. 2018, 32, 679–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry (ANZHFR) Steering Group. Australian and New Zealand Guideline for Hip Fracture Care: Improving Outcomes in Hip Fracture Management of Adults; Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry Steering Group: Sydney, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Brainsky, A.; Glick, H.; Lydick, E. The economic cost of hip fractures in community dwelling older adults: A prospective study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1997, 45, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haentjens, P.; Autier, P.; Barette, M. Belgium hip fracture study group. The economic cost of hip fractures among elderly women. A one-year prospective, observational cohort study with matched-pair analysis. Belgium Hip Fracture Study Group. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2001, 83, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiktorowicz, M.E.; Goeree, R.; Papaioannou, A. Economic implications of hip fracture: Health service use, institutional care and cost in Canada. Osteoporos Int. 2001, 12, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahota, O.; Morgan, N.; Moran, C.G. The direct cost of acute hip fracture care in care home residents in the UK. Osteoporos Int. 2012, 23, 917–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khow, K.; McNally, C.; Shibu, P. Getting back on their feet after a hip fracture. MedicineToday 2016, 17, 30–39. [Google Scholar]

- Center, J.R. Fracture burden: What two and a half decades of dubbo osteoporosis epidemiology study data reveal about clinical outcomes of osteoporosis. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2017, 15, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archibald, M.M.; Ambagtsheer, R.; Beilby, J.; Chehade, M.; Gill, T.K.; Visvanathan, R.; Kitson, A.L. Perspectives of frailty and frailty screening: Protocol for a collaborative knowledge translation approach and qualitative study of stakeholder understandings and experiences. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kastner, M.; Perrier, L.; Munce, S.E.P. Complex interventions can increase osteoporosis investigations and treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2018, 29, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Guideline: Recommendations on Digital Interventions for Health System Strengthening; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Jin, W.; Kim, D.H. Design and implementation of e-health system based on semantic sensor network using IETF YANG. Sensors 2018, 18, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henriquez-Suarez, M.; Becerra-Vera, C.E.; Laos-Fernandez, E.L.; Espinoza-Portilla, E. Evaluation of electronic health programs in Peru: Multidisciplinary approach and current perspective. Rev. Peru. Med. Exp. Salud. Publica. 2017, 34, 731–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. (Eds.) Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute. Available online: https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org (accessed on 15 February 2018).

- Joanna Briggs Institute, The University of Adelaide. Systematic Review Register. 2019. Available online: https://www.joannabriggs.org/resources/systematic_review_register?combine=&items_per_page=10&order=title&sort=asc (accessed on 18 March 2019).

- Munn, Z.; Aromataris, E.; Tufanaru, C.; Stern, C.; Porritt, K.; Farrow, J.; Lockwood, C.; Stephenson, M.; Moola, S.; Lizarondo, L.; et al. The development of software to support multiple systematic review types: The Joanna Briggs Institute System for the Unified Management, Assessment and Review of Information (JBI SUMARI). Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2019, 17, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufanaru, C.; Zachary, M.; Stephenson, M.; Aromataris, E. Fixed or random effects meta-analysis? Common methodological issues in systematic reviews of effectiveness. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. Sept. 2015, 13, 196–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegrante, J.P.; Peterson, M.G.E.; Cornell, C.N. Methodological challenges of multiple-component intervention: Lessons learned from a randomized controlled trial of functional recovery after hip fracture. HSS J. 2007, 3, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessette, L.; Davison, K.S.; Jean, S.; Roy, S.; Ste-Marie, L.G.; Brown, J.P. The impact of two educational interventions on osteoporosis diagnosis and treatment after fragility fracture: A population-based randomized controlled trial. Osteoporos Int. 2011, 22, 2963–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.C.; Guy, P.; Ashe, M.; Liu-Ambrose, T.; Khan, K. Hip watch: Osteoporosis investigation and treatment after a hip fracture: A 6-month randomized control trail. J. Gerentology Med. Sci. 2007, 62, 888–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaco, D.; Toma, E.D.; Gardin, L.; Giordano, S.; Castiglioni, C.; Vallero, F.A. Single postdischarge telephone call by an occupational therapist does not reduce the risk of falling in women after hip fracture: A randomized control trail. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2015, 151, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Langford, D.P.; Fleig, L.; Brown, K.C. Back to the future-feasibility of recruitment and retention to patient education and telephone follow-up after hip fracture: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2015, 9, 1343–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaglal, S.B.; Donescu, O.S.; Bansod, V.; Laprade, J. Impact of a centralized osteoporosis coordinator on post-fracture osteoporosis management: A cluster randomized control trail. Osteoporos Int. 2012, 23, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majumdar, S.R.; Johnson, J.A.; McAlister, F.A. Multifaceted intervention to improve diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis in patients with recent wrist fracture: A randomized control trail. CMAJ 2008, 178, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Halloran, P.D.; Shields, N.; Blackstock, F.; Wintle, E.; Taylor, N.F. Motivational interviewing increases physical activity and self-efficacy in people living in the community after hip fracture: A randomized control trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2016, 30, 1108–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, S.; Beaulieu, M.; Beaulieu, M.C.; Cabana, F.; Boire, G. Priming primary care physicians to treat osteoporosis after a fragility fracture: An integrated multidisciplinary approach. J. Rheumatol. 2013, 40, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwanpasu, S.; Aungsuroch, Y.; Jitapanya, C. Post-surgical physical activity enhancing program for elderly patients after hip fracture: A randomized control trail. Asian Biomed. 2014, 8, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedra, M.; Finkelstein, J. Feasibility of post-acute hip fracture telerehabilitation in older adults. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2015, 210, 469–473. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, P.F.; Emiliozzi, S.; McCabe, M.M. Telephone counselling to improve osteoporosis treatment adherence: An effectiveness study in community practice settings. Am. J. Med. Qual. 2007, 22, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, L.; Cameron, C.; Hawker, G. Development of a multidisciplinary osteoporosis telehealth program. Telemed. Ehealth 2007, 14, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tappen, R.M.; Whitehead, D.; Folden, S.L.; Hall, R. Effect of a video intervention on functional recovery following hip replacement and hip fracture repair. Rehabil. Nurs. 2003, 28, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tousignant, M.; Giguere, A.M.; Morin, M. In-home telerehabilitation for proximal humerus fractures: A pilot study. Int. J. Telerehabilitation 2014, 6, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Report on Ageing and Health; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- World Health Organization. Integrated Care for Older People: Guidelines on Community-Level Interventions to Manage Declines in Intrinsic Capacity; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ganda, K.; Puech, M.; Chen, J.S. Models of care for the secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2013, 24, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian and New Zealand Bone and Mineral Society. Australian and New Zealand Bone and Mineral Society Position Paper on Secondary Fracture Prevention Programs: A Call to Action. Available online: https://www.anzbms.org.au/downloads/ANZBMSPositionPaperonSecondaryFracturePreventionApril2015.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2018).

- Joshi, R.; Thrift, A.G.; Smith, C. Task-shifting for cardiovascular risk factor management: Lessons from the Global Alliance for Chronic Diseases. BMJ Glob. Health 2018, 3, e001092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mdege, N.D.; Chindove, S.; Ali, S. The effectiveness and cost implications of task-shifting in the delivery of antiretroviral therapy to HIV-infected patients: A systematic review. Health Policy Plan. 2013, 28, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Be healthy be Mobile: A Handbook on How to Implement Mageing; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- National Academy of Engineering (US) and Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Engineering and the Health Care System; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; ISBN 10: 0-309-09643-X.

- Spieth, P.M.; Kubasch, A.S.; Penzlin, A.I. Randomized controlled trials- a matter of design. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2016, 12, 1341–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1A Randomised controlled trials (N = 10). | |||||||||||||||

| Study | Year | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 | Q13 | Overall Appraisal |

| Allegrante et al. [23] | 2007 | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | No | Unclear | Yes | No | No | Yes | Unclear | Yes | No | 4 (31%) |

| Davis et al. [25] | 2007 | Unclear | Unclear | No | Unclear | No | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 5 (38%) |

| Majumdar et al. [29] | 2008 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 11 (85%) |

| Bessette et al. [24] | 2011 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Unclear | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Unclear | No | 4 (31%) |

| Jaglal et al. [28] | 2012 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 11 (85%) |

| Roux et al. [31] | 2013 | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | 7 (54%) |

| Suwanpasu et al. [32] | 2014 | Yes | No | Unclear | No | No | No | Yes | Unclear | No | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | 5 (38%) |

| Langford et al. [27] | 2015 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | 7 (54%) |

| Monaco et al. [26] | 2015 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 9 (69%) |

| O’Halloran et al. [30] | 2016 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | 9 (69%) |

| 70% | 60% | 70% | 0% | 10% | 50% | 90% | 70% | 30% | 100% | 20% | 80% | 70% | |||

| JBI critical appraisal checklist questions for RCTs | |||||||||||||||

| Q1 | Was true randomisation used for assignment of participants to treatment groups? | ||||||||||||||

| Q2 | Was allocation to treatment groups concealed? | ||||||||||||||

| Q3 | Were treatment groups similar at the baseline? | ||||||||||||||

| Q4 | Were participants blind to treatment assignment? | ||||||||||||||

| Q5 | Were those delivering treatment blind to treatment assignment? | ||||||||||||||

| Q6 | Were outcomes assessors blind to treatment assignment? | ||||||||||||||

| Q7 | Were treatment groups treated identically other than the intervention of interest? | ||||||||||||||

| Q8 | Was follow up complete and if not, were differences between groups in terms of their follow up adequately described and analysed? | ||||||||||||||

| Q9 | Were participants analysed in the groups to which they were Randomised? | ||||||||||||||

| Q10 | Were outcomes measured in the same way for treatment groups? | ||||||||||||||

| Q11 | Were outcomes measured in a reliable way? | ||||||||||||||

| Q12 | Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | ||||||||||||||

| Q13 | Was the trial design appropriate, and any deviations from the standard RCT design | ||||||||||||||

| (individual randomisation, parallel groups) accounted for in the conduct and analysis of the trial? | |||||||||||||||

| 1B Quasi-experimental studies (N = 5). | |||||||||||||||

| SR No | Study | Year | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Overall Appraisal | |||

| 1 | Tappen et al. [36] | 2003 | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6 (67%) | |||

| 2 | Cook et al. [34] | 2007 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8 (89%) | |||

| 3 | Dickson et al. [35] | 2008 | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | No | No | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | 1 (11%) | |||

| 4 | Tousignant et al. [37] | 2014 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 (78%) | |||

| 5 | Bedra et al. [33] | 2015 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | No | Yes | Unclear | Yes | No | No | 4 (44%) | |||

| Response rate | 100% | 60% | 20% | 20% | 80% | 40% | 80% | 60% | 60% | ||||||

| JBI critical appraisal checklist questions for Quasi-experimental studies | |||||||||||||||

| Q1 | Is it clear in the study what is the ‘cause’ and what is the ‘effect’ (i.e., there is no confusion about which variable comes first)? | ||||||||||||||

| Q2 | Were the participants included in any comparisons similar? | ||||||||||||||

| Q3 | Were the participants included in any comparisons receiving similar treatment/care, other than the exposure or intervention of interest? | ||||||||||||||

| Q4 | Was there a control group? | ||||||||||||||

| Q5 | Were there multiple measurements of the outcome both pre and post the intervention/exposure? | ||||||||||||||

| Q6 | Was follow up complete and if not, were differences between groups in terms of their follow up adequately described and analysed? | ||||||||||||||

| Q7 | Were the outcomes of participants included in any comparisons measured in the same way? | ||||||||||||||

| Q8 | Were outcomes measured in a reliable way? | ||||||||||||||

| Q9 | Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | ||||||||||||||

| SR No | Author/Year Methodological Quality (H, M, L) ** | Intervention | Outcome | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Majumdar et al. (2008) [29] H | The intervention consisted of three component intervention; firstly, brief telephonic counselling by an experienced registered nurse. These messages emphasise on at a high risk osteoporosis and future fracture, requiring bone mineral test followed by appropriate treatment through bisphosphonates or other alternative treatments like calcitonin, hormone replacement therapy, raloxifine. Beyond delivering these messages, the registered nurse also answered questions and allayed any concerned expressed by the patients about their treatment. The nurse also emphasised on the importance of speaking to their physician about their health condition. Secondly, patient specific reminder was sent to their respective physician with the same set of messages. Thirdly, summary of evidence-based actionable osteoporosis guideline, with endorsements from 5 local opinion leaders were sent to the physicians | Primary outcome was starting treatment with a bisphosphonate within 6 months after the fracture. This was measured using patient self-report and confirmed through dispensing records of local community pharmacies. There was 100% agreement between self-reporting and dispensing records. Secondary outcome was Bone mineral density (BMD) test and a composite measure of quality, referred to as guideline concordant or “appropriate care” defined as having undergone a BMD test and receiving bisphosphonate treatment if bone mass was low or osteoporosis. | Median age reported was 60 years (IQR 55–68 years). The findings from this study suggests that 22% (30) of the intervention group achieved primary outcome of bisphosphonate treatment for osteoporosis in comparison to only 7% (10) in the control group (RR 2.6, 95% CI 1.3–5.1, p = 0.008). By the end of the study, 66% received both calcium and vitamin D in the intervention group verses 43% with control group (RR 1.6, 95% CI 1.2–1.9, p = 0.001). Similarly, 52% (71) of the patients in the intervention group undertook BMD test compared to 18% (24) in control group (RR 2.8, 95% CI 1.9–4.2, p < 0.001). Of these, who had BMD test, 28% reported to have normal bone mass, 52% osteopenia and 20% osteoporosis at either hip or spine. Appropriate care was received by 38% of patients within the intervention group in compared to 11% in the control group (RR 3.1, 95% CI 1.8–5.3, p < 0.001). further, when the results were stratified by sex, men in the intervention group were less likely than women to receive appropriate care as 15% and 44% respectively. |

| 2 | Jaglal et al. (2012) [28] H | The intervention involved a physiotherapist as a centralised coordinator for following up patients and their physicians, provided evidence-based recommendations about the fracture risks and treatment of osteoporosis and assist with multidisciplinary consultation for patients with complex need, if needed. Patients received telephonic counselling about the risk of future fractures, BMD test and treatment of osteoporosis and follow-up with their physician. The primary care physician received a letter about the patient around the risk of future fracture, importance of BMD test, osteoporosis treatment using bisphosphonates or other alternative medications and availability of telehealth multidisciplinary consultation at a tertiary care hospital, in case of complex cases. Physicians also received pocket cards containing best-practice recommendations according to the recent Canadian guidelines. Outcomes | The primary outcome in was the proportion of patients self-reporting “appropriate management” defined as receiving within 6 months of fracture, either and osteoporosis medication (bisphosphonate, raloxifen or teriparatide) or normal BMD and prevention advise. Secondary outcomes were; the proportion of patients with a physician visit to discuss osteoporosis after fracture and the proportion for which BMD was scheduled or performed | Mean age was 66 years. The study reported a significant improvement in the osteoporosis management within the intervention group (32% vs. 20%, p = 0.007); analysis carried out as intention-to-treat. Further, in the intervention group, 23% had normal BMD, 22% treatment in comparison to 9% and 17% respectively in the control group. Whereas, with straight comparison, proportionately BMD test was reported to be higher in the intervention group than control group (57% vs. 21%, OR-4.8, 95% CI 3.0–7.0, p < 0.0001). Similarly, the intervention resulted in the majority of patients having a discussion about osteoporosis with their physician (82% vs. 55%, OR-3.8, 95% CI 2.3–6.3, p < 0.0001). |

| 3 | Bessette et al. (2011) [24] L | There were two intervention groups; written material and videocassette and written material group. The former received educational material on osteoporosis in the form of a two page document with concise information on the elevated risk for a new fracture, the importance of BMD and a summary of non-pharmacological therapies. Participants were invited to provide their respective primary care physician with an official summary of Canadian best practice guideline on osteoporosis. The videocassette group, in addition to written materials, received a 15-min educational video on osteoporosis which consisted of more comprehensive information on osteoporosis diagnosis and treatment as well as complications associated with fragility fractures | The primary objective of the study was to evaluate the impact of the two educational interventions on the diagnosis and treatment rates for osteoporosis after approximately 12 months following randomisation | In the group of women with no diagnosis or treatment at randomization, diagnosis of osteoporosis after follow-up occurred in 12%, 15%, and 16% of women within control, written material and videocassette and written material groups respectively. The rate of diagnosis for both intervention groups combined was 15%. Whereas, treatment rates were 8%,12% and 11% respectively in the same groups and if both interventions combined, it was 11%. In the group, without treatment at randomisation, at the follow-up, osteoporosis therapy was initiated in 10%, 13% and 15% respectively while combining the intervention; it would result in 13%. |

| 4 | Davis et al. (2007) [25] L | The intervention consisted of patient empowerment and physician alerting (PEPA) system; usual care for the fracture including surgical treatment, osteoporosis information and a letter for participants that encouraged them to return to their PCPs for further investigation, a request for participants to take a letter from the orthopaedic surgeon to the PCP alerting them to the hip fracture and encourage osteoporosis investigation, and telephonic call at 3 and 6 months to determine whether osteoporosis investigation and treatment had occurred | BMD test and bisphosphonate therapy at 6 months | In the PEPA (intervention) group, 15 (54%) were prescribed bisphosphonates therapy, 8(29%) BMD scan, 11(39%) calcium and vitamin D and 9(32%) exercises. Whereas, within the control group, none of the patients received any intervention, except 30% of them were prescribed calcium and vitamin D |

| 5 | Roux et al. (2013) [31] M | The intervention included two groups- Minimum (MIN) and Intensive (INT). MIN involved a coordinator to explain the patient, verbally and in writing, the casual link between fragility fracture and osteoporosis and the importance of contacting their primary care physician (PCP). A standard letter notified PCP of their patient’s fragility fracture status, explained the rationale and importance of rapid treatment of osteoporosis and outlined the appropriate investigations and treatment available and suggesting investigations and empirical treatments, irrespective of the BMD scores. Trained personnel made follow-up telephone calls at 6 and 12 months. In addition to collection of data, the importance of osteoporosis treatment was stressed and suggestions to increase adherence to osteoporosis medication was discussed. Whereas, within the INT group, same process was followed but in addition screening blood test were prescribed and patients were given a written prescription for BMD test. Blood test were conducted for serum calcium, phosphate, creatinine, alkaline phosphatase, and 25(OH) vitamin D levels, total blood count and plasma protein electrophoresis. Results were sent the respective PCPs with a letter stating that an incident fragility fracture usually indicates a need for treatment, irrespective of BMD results. When lab abnormalities were identified during screening, individualised counselling was given in writing to the PCP. Further, any PCP could contact one of the team members to discuss on how to manage the patient, if required. Similarly, telephonic follow-up was performed at 4, 8 and 12 months. | BMD test and osteoporosis therapy confirmed with the patients’ pharmacists at one year | Median age was 65 years (IQR 57–76 years) including 82% as females. At 12 months follow-up, the rates of current osteoporosis treatment were significantly higher in the intervention group than in the control group with no significant differences between the two intervention groups. Further, according to self-reports, around 45% of all patients underwent BMD testing during the first year, including 66% in the INT group whereas, around 34% within control and MIN groups each |

| 3A Targeted Patient Communication * | ||||

| SR No | Author/Year Methodological Quality (H, M, L) *** | Intervention | Outcome | Results |

| 1 | Allegrante et al. (2007) [23] L | Motivational videotape and a corresponding booklet around falls prevention self-efficacy, in addition an in-hospital peer support visit and 8-weeks out-patient physical therapy consisting of tailored exercises and progressive muscle strengthening training. | Functional status was assessed using 36-item short form health survey (SF-36) as the study’s primary outcome at 6-months follow-up | All the intervention patients were exposed to at least one of the three intervention components, i.e., videotape, strength training and peer counselling. However, only 34% of all the participants were able to complete full 6-months follow-up assessments (Intervention 32 vs. control 27). Patients within the intervention group had a significant positive change in the role-physical scale as compared to the control group (mean score, −11 ± 33 Vs −37 ± 41, p = 0.03). No significant post intervention differences were observed in the change on the physical functioning and social functioning scales and other domains like bodily pain, general health, vitality, role-emotional and mental health |

| 2 | Tappen et al. (2003) [36] M | Consisted of two parts; videotaping the study participants during their physical therapy sessions and showing one of the two generic educational videos that were produced for this study, depending upon the type of surgical repair, i.e., total hip replacement or arthroplasty, using plates or screws. Generic educational videos depict all aspects of physical recovery through the use of demonstrations and interviews with actual patients. The major focus of these generic tapes was the need to increase activity daily and intended to reinforce instructions that were given during rehabilitation and applied while moving in home or the respective community setting. Symptoms of anxiety and depression after hip surgery were also addressed using psychosocial adjustments. On the other hand, individual videos consisted of intervention participants being videotaped during their respective physical therapy sessions at regular intervals throughout their stay to record their progress. These videos show the therapist instructing the individual participants in the use of assistive devices, ambulance techniques and procedures for transferring. The tapes also document individualised instructions on exercises and show the therapist helping the participant do the prescribed exercises correctly. Participants were given both videotapes to take home for review | Physical activity performance measured through the distance walked in feet and time in seconds at three months post-discharge. | At three months post-discharge, time walked in seconds was significant, intervention [314.79 (SD-139.59)] Vs control [204.77 (179.70)]. |

| Though analysis comparing the two groups did not differ significantly on self-care, functional ability, coping and performance of independent ADLs; results for coping approached statistical significance. | ||||

| 3 | Cook et al. (2007) [34] H | “Scriptassist” telephonic counselling program, intervention delivered telephonically by one of the four registered nurses at the scriptassist call centre. This communication was based upon the principles of motivational interviewing, focused on patient’s motivation for treatment, problem solving to resolve barriers to adherence, improve self-efficacy and helping patient practice skills to self-manage their own chronic conditions. Calls focused on relationship building and answering questions to encourage participant’s motivation for treatment. | Adherence to osteoporosis medication at 6 months based on pharmacy and clinical interview data | Among the high risk participants for fragility fractures, up to five telephonic contacts (median) were made with average call duration of 15 min. The participants were followed up for an average of 4.1 months after the start of the treatment (range 0–14 months). In terms of 6-months follow-up, 188 patients completed pharmacy data whereas, 255 patients with interview data. Adherence to treatment was reported at 6 months around 70% in this study, by both methods, compared to 46% in the representative population group reported through a national survey. |

| 4 | Monaco et al. (2015) [26] M | The intervention included at least 3 h during the stay of the patients, an occupational therapist to assess home hazards of falling based upon a standard checklist to determine future risk of falling and subsequent recommendations were provided. The patients also received a brochure describing falls prevention strategies. Further, geriatric evaluation was conducted for health optimisation and possibility of withdrawing medications in use which may increase the risk of falls and oral supplements of vitamin D and calcium were prescribed to continue after discharge from the hospital. Single telephonic call by an occupational therapist after discharge to check for environmental hazards, behaviour in ADL, use of assistive devices and reinforced targeted modifications to prevent falls. | Proportion of falls between two groups at 6 months | As an outcome measure, no differences were found in the proportion of fallers between the two groups (RR 1.06, CI 0.48–2.34) |

| 5 | O’Halloran et al. (2016) [30] M | Telephonic-based motivational interviewing eight times during the study participation period, lasting about 30 min per session and one call per week. The intervention was delivered by a trained physiotherapist in motivational interviewing. The intervention was designed to address issues associated with ambivalence about change in activity, such as beliefs about physical activity, low confidence and fear of falling which may prevent people after hip fracture from being more active. | Participants were asked to wear an accelerometer fitted to the thigh for a seven-day period at baseline and then again after the intervention phase, to measure the amount of physical activity they completed (ActivPal). Physical activity was recorded as the number of steps taken per day, the time spent walking per day and the time spent sitting or lying each day (sedentary behaviour). Secondary outcomes were health-related quality of life assessed through AQOL 8-D | Physical activity seemed to be improved in the intervention group compared with the control group, measured by daily steps and time spent walking; 26% and 22% respectively. Intervention group improved in mobility-related confidence but no difference observed with respect to mobility-related function. Further, the intervention group also demonstrated improvements in health-related quality of life (5.8, CI 1.2 to 10.4, p = 0.015), anxiety (−1.8, CI −3.0 to −0.6, p = 0.004) and depression scores (−3.7 CI −6.3 to −1.1, p = 0.010). |

| 6 | Suwanpasu et al. (2014) [32] L | Physical activity enhancing program (PEP) which composed of four phases, covered five sessions of implementation within seven weeks post-hip fracture surgery, but combined both phone calls and face-to-face interactions. Phase-1 assess existing self-efficacy, outcome expectations for physical activity and being ready to change physical activity. Phase-2 involved preparation for strengthening self-efficacy and outcome expectations offered through individual education and training in structural exercise and daily life physical activity and the benefits of regular behaviour, verbal encouragement by credible sources, seeing others experience and visual cueing (physical activity after hip fracture booklet, poster and flipbook), and short and long-term goal setting. Phase-3 included practice for strengthening self-efficacy and outcome expectations, involved everyday workouts of structural exercises and daily life physical activity, re-evaluating goal setting, self-monitoring and re-interpretation and control of unpleasant sensations associated with physical activity. Phase-4 involved evaluation of physical activity behaviour, including the energy expenditure of physical activity. | Information on physical activity was collected at 6-weeks after discharge. | At 6-weeks post-discharge, there was a significant increase in physical activity in the intervention group compared with the control group after controlling for pre-fracture physical activity with an effect size of 0.18 (<0.01). The amount of overall physical activity of the intervention group significantly increased by 961.37 MET/min/week over the control group. Physical activity was effective in 65% of the PEP (intervention) group. The ratio of efficiency (markedly effective and effective) induced by the PEP was higher than that induced by usual care (65% vs. 48%) and similarly ratio of markedly effective induced by the PEP was significantly higher than that induced by usual care 30% vs. 8%). |

| 7 | Langford et al. (2015) [27] M | The intervention included one hour in-hospital educational session with a trained health professional, using the hip fracture recovery manual and four educational videos. The content of this education program followed a standard format as guided by the manual but was individualised for each participant, including a description of the type of fracture sustained, how it was surgically fixated, red flags to watch out for during the recovery phase, an exercise program (home-based reducing both the rate and risk of future falls), practical information about future falls prevention, review of home safety and environmental hazards and mobility and recovery goal setting. The videos were viewed at the bedside using a tablet and headphone. Teach-back method was used which intends to clarify and check participants’ understanding of materials and ensured that the participants were able to provide a verbal summary of the education provided to them. After discharge, the trained health professional telephoned participants up to five times in the first 4 months following hip fracture to provide further encouragement, falls prevention information, coaching to remain active, problem solving skills, mobility goal setting, and advise to help participants maintain and increase their prescribed home exercises. The content of the sessions classified according to the CALO-RE (Coventry, Aberdeen and London-Redefined) taxonomy of behaviour change. | This study was a pilot study and the primary outcome of the trial was feasibility measured by recruitment rate and participant retention | The recruitment and retention rate of participants in the study was 42% and 90% respectively |

| 3B Telemedicine, personal health tracking and healthcare provider decision support ** | ||||

| SR No | Author/Year | Intervention | Outcome | Results |

| 1 | Bedra et al. (2015) [33] L | Home automated telemanagement (HAT) system to support individualised exercise program which consisted of a home unit, HAT server and a clinician unit. Home unit guides patients at home in routinely following their exercise program in a safe and effective way. The unit sends this information through a landline or wireless connection to the HAT information system. This system is able to monitor progress in terms of patient adherence and compare the results with the prescribed level of activities by the respective clinician. On the other hand, clinician unit can be any web-enabled devise. This system provides tailored feedback to the patients motivates them based on the behavioural profile and notifies clinicians. The system can further empower patients with self-paced interactive multimedia education on the major aspects of hip fracture rehabilitation program. This education module can be individualised to each patient’s specific needs and is based on the concepts of social cognitive theory. | Exercise self-efficacy, physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health problems, social functioning, health transition and client satisfaction at 30-day | Overall, 14 patients were recruited to test the telerehabilitation system at their homes. Mean age was around 77 (±9), More than 50% never had any computer experience in their lifetime. The telerehabilitation system was successfully used by the hip fracture patients at their home regardless of their socioeconomic or computer literacy background. At the end of 30-day telerehabilitation program, exercise self-efficacy (9 ± 1 vs. 6 ± 3, p = 0.01), physical functioning (71 ± 31 vs. 38 ± 27, p = 0.009), role-limitations due to physical health problems (17 ± 12 vs. 6 ± 10, p = 0.05), social functioning (85 ± 28 vs. 54 ± 31, p = 0.01), health transition (22 ± 18 vs 47 ± 40, p = 0.05) and client satisfaction (31 ± 0.46 vs. 27 ± 4, p = 0.04) apparently seems to have improved. Also, physical activity in terms of hours per week demonstrated a significant increase (31 ± 14 vs. 24 ± 14, p = 0.04). Adherence to the telerehabilitation over a 30-day program was reported to be 90% and above in most domains. |

| 2 | Dickson et al. (2007) [35] L | Involved setting up of network studio within the osteoporosis research department at a Women’s college hospital. The technology included a set-top videoconferencing system with a 27 inch television. Space was allocated for two desks; one for telehealth coordinator and one for health professionals to allow for them to move and demonstrate various exercises/activities to the patients during the consultation. Each healthcare professional individually consulted the patient via a telehealth, providing them with the same information they would receive in an in-person consult. | Knowledge about osteoporosis, confidentiality, and client satisfaction | The mean age was 56.5 years and the average length of telehealth consultation was around two hours and the length of follow-up was 15-min. The response rate to satisfaction survey questionnaire was 67%. Out of which, 58% rated telehealth consultation as excellent in comparison to in-person specialist consultation and 33% rated as a good experience. Almost all the participants expressed their intent to be using it again and recommend to their friends and family members. Prior to consultation, 73% described their knowledge about osteoporosis as fair and 27% as good but after consultation, only 10% described as fair, 30% good and 60% rated as excellent. When rating confidentiality, 83% patients felt completely comfortable discussing their health problems during their telehealth consultation |

| 3 | Tousignant et al. (2014) [37] M | The intervention based on a modular design, a generic platform was built, consisting of a videoconferencing unit to provide telerehabilitation program over eight consecutive weeks. The treatment program was delivered twice a day, every day, either supervised by a physiotherapist through telerehabilitation or unsupervised. Patients had two telerehab sessions in week 1, 3 and 5 and only one on weeks 2, 4, 6, 7 and 8. | Three outcome measures were evaluated; pain, shoulder ROM and upper limb function and additional satisfaction with health services received. | Each session lasted for about 30–45 min and divided into three parts; warm-up, treatment program and question period. The treatment program was adjusted for each patient according to the number of weeks, post fracture. Every exercise program involved four exercise types based on the orthopaedic physician’s specifications; stretching, pain control, active/active assisted ROM and muscle building. The physiotherapist also adjusted the progression of exercises according to the patient’s progress. Pain decreased significantly between pre and post intervention as indicated by the SF-MPQ score (difference of 10.6 ± 12.4, p = 0.003) and VAS (difference 26.3 ± 21.8, p = 0.001) which was greater than minimal clinically important difference (difference over 5/45 for total descriptors). The shoulder ROM difference was greater than the interrater minimal clinical difference (more than 5–10 degrees) for all. A difference of 42.1 ± 11.4 (p < 0) in the upper limb function was observed, greater than the minimal clinical difference (change over 15/100). Further, around 82% was the overall satisfaction, considered to be very good. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yadav, L.; Haldar, A.; Jasper, U.; Taylor, A.; Visvanathan, R.; Chehade, M.; Gill, T. Utilising Digital Health Technology to Support Patient-Healthcare Provider Communication in Fragility Fracture Recovery: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4047. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16204047

Yadav L, Haldar A, Jasper U, Taylor A, Visvanathan R, Chehade M, Gill T. Utilising Digital Health Technology to Support Patient-Healthcare Provider Communication in Fragility Fracture Recovery: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(20):4047. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16204047

Chicago/Turabian StyleYadav, Lalit, Ayantika Haldar, Unyime Jasper, Anita Taylor, Renuka Visvanathan, Mellick Chehade, and Tiffany Gill. 2019. "Utilising Digital Health Technology to Support Patient-Healthcare Provider Communication in Fragility Fracture Recovery: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 20: 4047. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16204047

APA StyleYadav, L., Haldar, A., Jasper, U., Taylor, A., Visvanathan, R., Chehade, M., & Gill, T. (2019). Utilising Digital Health Technology to Support Patient-Healthcare Provider Communication in Fragility Fracture Recovery: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(20), 4047. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16204047