Evaluation of a Violence-Prevention Programme with Jamaican Primary School Teachers: A Cluster Randomised Trial

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

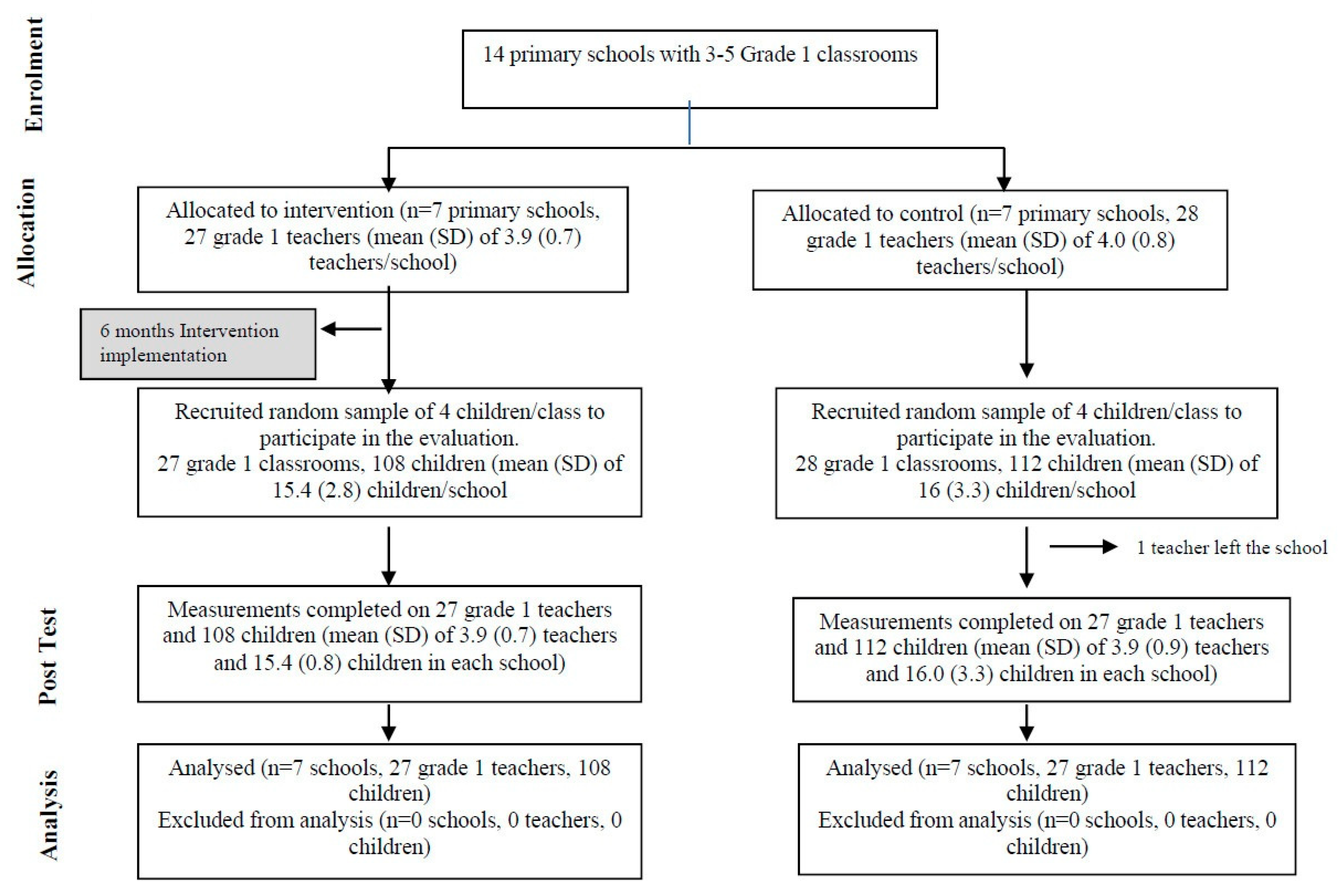

2.1. Study Design and Sample

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. Primary Outcomes

2.2.2. Secondary Outcomes

2.2.3. Procedure for Data Collection and Quality Control

2.3. Sample Size

2.4. Teacher Reports on Use of Corporal Punishment

2.5. The Intervention

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample

3.2. Intervention Implementation

3.3. Findings from the Impact Evaluation

3.4. Findings from Teacher Reports of Corporal Punishment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hillis, S.; Mercy, J.; Amobi, A.; Kess, H. Global prevalence of past-year violence against children: A systematic review and minimum estimates. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20154079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gershoff, E.T. School corporal punishment in global perspective: Prevalence, outcomes and efforts at intervention. Psychol. Health Med. 2017, 22, 224–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkey, M.; Hosein, M.; Morton, I.; Purgato, M.; Adi, A.; Kurzrok, M.; Kohrt, B.A.; Tol, W.A. Psychosocial interventions for disruptive behaviour problems in children in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2018, 59, 982–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knerr, W.; Gardner, F.; Cluver, L. Improving positive parenting skills and reducing harsh and abusive parenting in low and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Prev. Sci. 2013, 14, 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puffer, E.S.; Green, E.P.; Chase, R.M.; Sim, A.L.; Zayzay, J.; Friis, F.; Garcia-Rolland, E.; Boone, L. Parents make the difference: A randomized controlled trial of a parenting intervention in Liberia. Glob. Ment. Health 2015, 2, e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachman, J.M.; Cluver, L.; Ward, C.L.; Hutchings, J.; Mlotshwa, S.; Wessels, I.; Gardner, F. Randomized controlled trial of a parenting program to reduce the risk of child maltreatment in South Africa. Child Abuse Negl. 2017, 72, 338–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Devries, K.M.; Knight, L.; Child, J.C.; Mirembe, A.; Nakuti, J.; Jones, R.; Sturgess, J.; Allen, E.; Kyegombe, N.; Parkes, J.; et al. The good school toolkit for reducing physical violence from school staff to primary school students: A cluster-randomised controlled trial in Uganda. Lancet Glob. Health 2015, 385, e378–e386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershoff, E.T. Corporal Punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 128, 539–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, R.; Byambaa, M.; De, R.; Butchart, A.; Scott, J.; Vos, T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker-Henningham, H.; Meeks-Gardner, J.; Chang, S.; Walker, S. Experiences of violence and deficits in academic achievement among primary school aged children in Jamaica. Child Abuse Negl. 2009, 33, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devries, K.M.; Child, J.C.; Allen, E.; Walakira, E.; Parkes, J.; Naker, D. School violence, mental health and educational performance in Uganda. Pediatrics 2014, 133, e129–e137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellam, S.; Ling, X.; Merisca, R.; Brown, H.; Ialongo, N. The effect of the level of aggression in the first grade on the course and malleability of aggressive behaviour into middle school. Dev. Psychopathol. 1998, 10, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, M.; Walker, S.; Fernald, L.; Andersen, C.; DiGirolamo, A.; Lu, C.; Fink, G.; Shawar, Y.; Shiffman, J.; Devercelli, A.; et al. Early childhood development coming of age: Science through the life course. Lancet 2016, 389, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.; Wachs, T.; Grantham-McGregor, S.; Black, M.; Nelson, C.; Huffman, S.; Baker-Henningham, H.; Chang, S.; Hamadani, J.; Lozoff, B.; et al. Inequality begins in early childhood: Risk and protective factors for early child development. Lancet 2011, 3781, 325–338. [Google Scholar]

- Samms-Vaughan, M. Profiles: The Jamaican Preschool Child. The Status of Early Childhood Development in Jamaica; Planning Institute of Jamaica: Kingston, Jamaica, 2005.

- Baker-Henningham, H.; Scott, S.; Jones, K.; Walker, S. Reducing child conduct problems and promoting social skills in a middle income country: Cluster randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 2012, 201, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker-Henningham, H.; Walker, S.; Powell, C.; Meeks-Gardner, J.M. A pilot study of the Incredible Years teacher training programme and a curriculum unit on social and emotional skills in community preschools in Jamaica. Child Care Health Dev. 2009, 35, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker-Henningham, H.; Walker, S. Effect of transporting an evidence-based violence prevention intervention to Jamaican preschools on teacher and class-wide child behavior: A cluster randomised trial. Glob. Ment. Health 2018, 5, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker-Henningham, H. The Irie Classroom Toolbox: Developing a violence prevention, preschool teacher training program using evidence, theory and practice. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2018, 1419, 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker-Henningham, H.; Francis, T. Parents’ use of harsh punishment and young children’s behaviour and achievement: A longitudinal study of Jamaican children with conduct problems. Glob. Ment. Health 2018, 5, e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianta, R.C.; La Paro, K.M.; Hamre, B.K. Classroom Assessment Scoring System™: Manual K-3; Paul H Brookes Publishing: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sabol, T.J.; Soliday Hong, S.L.; Pianta, S.C.; Burchinal, M.R. Can rating Pre-K programs predict children’s learning. Science 2013, 341, 845–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva, D.; Weiland, C.; Barata, M.; Yoshikawa, H.; Snow, C.; Trevino, E.; Rolla, A. Teacher-child interactions in Chile and their associations with prekindergarten outcomes. Child Dev. 2015, 86, 781–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araujo, M.; Carneiro, P.; Cruz-Aguayo, Y.; Schady, N. Teacher quality and learning outcomes in kindergarten. Q. J. Econ. 2016, 131, 1415–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker-Henningham, H.; Vera-Hernandez, M.; Alderman, H.; Walker, S. Irie Classroom Toolbox: A study protocol for a cluster randomised trial of a universal violence prevention program in Jamaican preschools. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e012166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, R.; Scott, S. Comparing the strengths and difficulties questionnaire and the child behaviour checklist: Is small beautiful? J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 1999, 27, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodcock, R.; McGrew, K.; Mather, N. Woodcock-Johnson III Tests of Achievement; Riverside Publishing: Itasca, IL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock, R.; Mather, N.; Schrank, F. Woodcock-Johnson III Diagnostic Reading Battery; Riverside Publishing: Itasca, IL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock, R.; McGrew, K.; Werder, J. Woodcock-McGrew-Werder Mini-Battery of Achievement; Riverside Publishing: Itasca, IL, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Donald, R.; Raver, C.; Hayes, T.; Richardson, B. Preliminary construct and concurrent validity of the preschool self-regulation assessment (PSRA) for field-based research. Early Child. Res. Q. 2007, 22, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radloff, L. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, V.P.; Wrench, J.S.; Gorham, J. Communication, Affect and Learning in the Classroom; Tapestry Press: Acton, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Teacher Self-Efficacy Scale. Available online: http://u.osu.edu/hoy.17/files/2014/09/Bandura-Instr-1sdm5sg.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2019).

- Han, S.S.; Weiss, B. Sustainability of teacher implementation of school-based mental health programs. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2005, 33, 665–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, T.C.; Glasziou, P.P.; Boutron, I.; Mine, R.; Perera, R.; Moher, D.; Altman, D.G.; Barbour, V.; Macdonald, H.; Johnston, M.; et al. Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014, 348, g1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiStefano, C.; Zh, M.; Mîndrilă, D. Understanding and using factor scores: Considerations for the applied researcher. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2009, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Rasbash, J.; Charlton, C.; Browne, W.J.; Healy, M.; Cameron, B. MLwiN Version 2.10; Centre for Multilevel Modelling, University of Bristol: Bristol, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Samms-Vaughan, M.; Lambert, M. The impact of polyvictimisation on children in LMICs: The case of Jamaica. Psychol. Health Med. 2017, 22 (Suppl. 1), 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansford, J.E.; Deater-Deckard, K. Childrearing discipline and violence in developing countries. Child Dev. 2012, 83, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker-Henningham, H.; Walker, S. A qualitative study of teachers’ perceptions of an intervention to prevent conduct problems in Jamaican pre-schools. Child Care Health Dev. 2009, 35, 632–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyegombe, N.; Namakula, S.; Mulindwa, J.; Lwanyaaga, J.; Naker, D.; Namy, S.; Nakuti, J.; Parkes, J.; Knight, L.; Walakira, E.; et al. How did the good school toolkit reduce the risk of past week physical violence from teachers to students? Qualitative findings on pathways of change in schools in Luwero, Uganda. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 180, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melendez-Torres, G.J.; Leijten, P.; Gardner, F. What are the optimal combinations of parenting intervention components to reduce physical child abuse recurrence? Reanalysis of a systematic review using qualitative comparative analysis. Child Abuse Rev. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnuson, K.; Schindler, H. Supporting children’s early development by building caregivers’ capacities and skills: A theoretical approach informed by new neuroscience research. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2019, 11, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansford, J.E.; Cappa, C.; Putnick, D.L.; Bornstein, M.H.; Deater-Deckard, K.; Bradley, R.H. Change over time in parents’ beliefs about and reported use of corporal punishment in eight countries with and without legal bans. Child Abuse Negl. 2017, 71, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naker, D. Preventing violence against children at schools in resource-poor environments: Operational culture as an overarching entry point. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, R.H.; Sugai, G. School-wide PBIS: An example of applied behaviour analysis implemented at a scale of social importance. Behav. Anal. Pract. 2015, 8, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, S.; Aber, J.L.; Behrman, J.R.; Tsinigo, E. Experimental impacts of the “Quality Preschool for Ghana” interventions on teacher professional well-being, classroom quality, and children’s school readiness. J. Res. Educ. Eff. 2018, 12, 10–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, S.; Torrente, C.; Frisoli, P.; Weisenhorn, N.; Shivshanker, A.; Annan, J.; Aber, J.L. Preliminary impacts of the “Learning to Read in a Healing Classroom” intervention on teacher well-being in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2015, 52, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayiwa, J.; Clarke, K.; Knight, L.; Allen, E.; Walakira, E.; Namy, S.; Merrill, K.G.; Naker, D.; Devries, K. Effect of the good school toolkit on school staff mental health, sense of job satisfaction and perceptions of school climate: Secondary analysis of a cluster randomized trial. Prev. Med. 2017, 101, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, S.J.; Lipsey, M.W. School-based interventions for aggressive and disruptive behaviour—Update of a meta-analysis. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2007, 33, S130–S143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshikawa, H.; Leyva, D.; Snow, C.E.; Trevino, E.; Weiland, C.; Gomez, G.J.; Moreno, L.; Rolla, A.; D’Sa, N.; Arbour, M.C. Experimental impacts of a teacher professional development program in Chile on preschool classroom quality and child outcomes. Dev. Psychol. 2015, 51, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozler, B.; Fernald, L.C.H.; Kariger, P.; McConnell, C.; Neuman, M.; Fraga, E. Combining preschool teacher training and parenting education: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. J. Dev. Econ. 2018, 133, 448–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, D.; Westbrook, J.; Pryor, J.; Durrani, N.; Sebba, J.; Adu-Yeboah, C. What the Impacts and Cost-Effectiveness of Strategies to Improve Performance of Untrained and Under-Trained Teachers in the Classroom in Developing Countries? EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Centre, Institute of Education, University of London: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stoolmiller, M.; Eddy, M.; Reid, J.B. Detecting and describing preventive intervention effects in a universal school-based randomized trial targeting delinquent and violent behaviour. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2000, 68, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Description of Measures Used | |

|---|---|

| Teachers Use of Violence Against Children 1 | Continuous observations of teacher behaviour over one school day using event sampling. Total score is the sum of teachers’ use of violence in each category. |

| Physical punishment | Hitting with hand, hitting with object, forcefully pushing or pulling, shaking, pinching, poking, throwing an object at the child, making the child stand or kneel in uncomfortable positions (e.g., stand with hands out to the side). |

| Verbal abuse | Calling the child by a derogatory name (e.g., idiot, dummy, fool), threatening physical punishment, threatening the child in way that would frighten them (e.g., threaten to lock them up), threatening to withhold food, rejection, encouraging other children to harm, insult or exclude the child (e.g., encouraging a child to hit another child). |

| Other abuse | Intimidation (e.g., banging a stick hard on the desk in front of a child), non-verbal threat (e.g., using stick/ruler to threaten child with physical punishment). |

| Observations of the Classroom Environment | Classroom observations over six 20 min periods on a seven point rating scale (1–7) over one school day: mean score over six observations used in analyses. |

| Class-wide child aggression 1 | The score for class-wide aggression reflects the frequency, intensity and number of children involved in aggressive acts. Higher scores indicate more aggression. |

| Class-wide child prosocial behaviour | The score for class-wide prosocial behaviour reflects the frequency, intensity and number of children involved in prosocial acts (i.e., sharing, helping and cooperating). Higher scores indicate more prosocial behaviour. |

| Levels of emotional support | Emotional support was measured using the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS)- K-3 [21]. The score is a composite of four rating scales: Positive Climate, Negative Climate, Teacher Sensitivity, and Regard for Student Perspectives. Higher scores indicate a more emotionally supportive environment. |

| Teachers’ Use of Violence (Binary) | Observations of teacher behaviour over two full days (binary variable). |

| Teachers’ use of violence | Event sampling of teachers’ use of violence against children (physical punishment, verbal abuse, other abuse) over one full school day and over five 20 min observation periods on another school day. The scores represent whether or not the teacher used physical violence, verbal abuse, other violence and violence of any type against children over the two days of observation. |

| Child behaviour | Assessed through teacher report. Total score for each scale used in the analyses. |

| Behavioural difficulties and prosocial skills | Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire by teacher report: a total difficulties (20 questions) and prosocial (5 questions) score were computed [26]. |

| School Achievement | Assessed through direct testing and tester ratings. Factor scores used in analyses. |

| Oral language skills | Understanding Directions and Story Recall from the Woodcock–Johnson III Tests of Achievement [27]. |

| Reading | Letter word identification and Passage Comprehension from the Woodcock–Johnson (WJ) III Diagnostic Reading Battery [28]. |

| Phonics | Word attack and spelling of sounds subscales from the Woodcock–Johnson III Diagnostic Reading Battery [28]. |

| Spelling | Spelling subscale from the Woodcock–Johnson III Tests of Achievement [27]. |

| Maths | Calculation and Reasoning and Concepts subscales from the Woodcock–McGrew–Werder Mini-Battery of Achievement [29]. |

| Self-regulation | Rated during the test session using eleven four point scales from the Preschool Self-Regulation Assessment: Assessor Report [30]. Items related to child attention and child impulse control. Higher scores indicate higher self-regulation. |

| Teacher Wellbeing | Assessed through teacher report. Factor score using in the analysis. |

| Depressive symptoms | Frequency of depressive symptoms using the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale [31]. The scale consists of 20 questions scored on a four point scale (0–3). Higher scores indicate higher levels of depressive symptoms. |

| Burnout | Teacher burnout measured using the Teacher Burnout Scale [32]. The scale consists of 20 questions scored on a five point scale (1–5). |

| Teaching self-efficacy | Four subscales from the Bandura’s Teaching Self-Efficacy Scale: instructional, disciplinary, enlisting parent involvement and creating a positive school climate [33]. The scale consists of 25 questions scored on a seven point scale (1–7). |

| Intervention | Control | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Teacher and Classroom Characteristics | n = 27 | n = 27 | |

| % female | 100% | 100% | 1.00 |

| % completed high school | 100% | 100% | 1.00 |

| % with a Dip.Ed or B.Ed | 100% | 100% | 1.00 |

| Teacher age 1 | 39.5 (10.9) | 43.2 (10.2) | 0.23 |

| Number of years teaching 1 | 14.9 (9.9) | 16.8 (9.8) | 0.50 |

| Number years teaching at this school 1 | 11.2 (9.7) | 10.0 (8.1) | 0.63 |

| No. children in class 1 | 30.2 (6.5) | 30.0 (5.2) | 0.91 |

| Child Characteristics | n = 108 | n = 112 | |

| Child age 1 | 7.00 (0.36) | 6.90 (0.30) | 0.01 |

| % male | 54 (50.5%) | 53 (49.5%) | 0.69 |

| Teacher and Classroom Outcomes | Intervention n = 27 | Control n = 27 |

| Primary Outcomes | ||

| Teachers’ use of violence over one school day (median, range) | 4 (0–70) | 12 (0–81) |

| Children’s class-wide aggression 2 | 4.16 (1.25) | 4.40 (1.20) |

| Secondary Outcomes | ||

| Emotional quality of classroom 2 | 4.10 (0.66) | 3.48 (0.51) |

| Children’s class-wide prosocial behaviour 2 | 2.33 (0.73) | 2.21 (0.67) |

| Teacher depression 3 (median, range) | 9.0 (0–46) | 8.0 (0–48) |

| Teacher burnout 4 | 33.8 (11.8) | 34.2 (12.2) |

| Teacher self-efficacy 5 (median, range) | 142 (72–172) | 127 (102–164) |

| Individual Child Outcomes | n = 108 | n = 112 |

| Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire | ||

| Behavioural difficulties 6 | 9.12 (6.50) | 9.55 (5.94) |

| Prosocial behaviour 7 | 6.82 (2.60) | 7.20 (2.36) |

| Child Academic Achievement | ||

| Understanding directions | 25.75 (6.51) | 24.00 (7.06) |

| Story recall | 30.22 (15.07) | 30.38 (18.28) |

| Letter word ID | 27.54 (9.09) | 28.00 (9.60) |

| Reading comprehension | 13.63 (6.30) | 14.01 (6.54) |

| Word attack, median (range) | 6 (2–31) | 6 (1–31) |

| Spelling of sounds | 20.41 (7.66) | 19.33 (7.58) |

| Spelling | 21.22 (5.66) | 21.88 (5.83) |

| Calculation | 7.49 (2.89) | 6.79 (3.16) |

| Maths reasoning (median, range) | 28 (18–35) | 27 (10–32) |

| Self-regulation 8 (median, range) | 31 (13–33) | 31 (15–33) |

| Measure | Regression Coefficient B (95% CI) | ICC 3 | Effect Size 4 (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Outcomes | ||||

| Teachers’ use of violence against children 5 | −0.38 (−0.68, −0.08) | 0.05 | −0.73 (−0.15, −1.31) | <0.0001 |

| Class-wide child aggression 6 | −0.24 (−0.88, 0.40) | 0.00 | −0.20 (−0.73, 0.33) | 0.47 |

| Secondary Outcomes: teacher and classroom outcomes | ||||

| CLASS: emotional support 6 | 0.62 (0.29, 0.95) | 0.09 | 1.22 (0.57, 1.87) | <0.0001 |

| Class-wide child prosocial behaviour 6 | 0.12 (−0.24, 0.48) | 0.00 | 0.18 (−0.36, 0.72) | 0.52 |

| Poor teacher wellbeing 7 | −0.11 (−0.63, 0.42) | 0.00 | −0.11 (−0.63, 0.43) | 0.69 |

| Secondary Outcomes: individual child outcomes | ||||

| Child behavioural difficulties 8 | −0.64 (−3.17, 1.89) | 0.06 | −0.11 (−0.53, 0.32) | 0.62 |

| Child prosocial behaviour 8 | −0.32 (−1.27, 0.63) | 0.03 | −0.14 (−0.54, 0.27) | 0.50 |

| Academic achievement factor 9 | −0.01 (−0.55, 0.55) | 0.21 | −0.004 (−0.54, 0.54) | 0·99 |

| Language & self-regulation factor 10 | 0.25 (−0.02, 0.52) | 0.00 | 0.25 (−0.02, 0.52) | 0·07 |

| Intervention n = 27 | Control n = 27 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No physical violence | 6 (22.2%) | 1 (3.7%) | 0.04 |

| No verbal abuse | 10 (37%) | 3 (11.1%) | 0.03 |

| No other violence | 22 (81.5%) | 13 (48.1%) | 0.01 |

| No violence of any type | 3 (11.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0.08 |

| Subtheme | Examples of Quotes |

|---|---|

| Reasons for using less corporal punishment (CP) | |

| The strategies work, so do not need to use CP (14) | “It lessen, put it this way, what I would normally slap them for, I don’t slap them for that anymore—because I have the strategies that helps me.” “I can’t tell when last I have to use the strap. I don’t need to use it. It has worked tremendously. The program make me not use it, all the skills, all of them work: the rules, the praise, strategic and labelled praise and friendship skills too.” |

| Children are better behaved (5) | “They are behaving in the way you want them to behave so you don’t have to reprimand them because they are actually doing what is expected of them.” “The more I use the strategies the more the appropriate behaviour is displayed. So that in itself, allowed me to use less.” |

| Teacher better able to stay calm (7) | “It helps me to be more relaxed than I used to be. I used to get easily upset but it has calmed me, helped me to relax and basically to be more understanding.” |

| Using the strategies is less stressful than using CP (5) | “Less strenuous on teacher. The energy you would use to slap them, you use the strategies. Saves you physically and mentally, voice don’t go and you don’t have to be hitting children.” “You feel more comfortable and more relaxed. So instead of doing corporal punishment—that really takes away from your peace and your sanity.” |

| Better relationship with children (5) | “It makes me see the good. I see children who are kind and helpful. So, it allows you to see them in another light. When you praise them—you see the good in them” |

| Reasons for continuing to use corporal punishment (CP) | |

| It works (5) | “Everybody pays attention, yes and they stop what they’re not supposed to do ’cause they’re afraid of the stick.” |

| CP is used at home (5) | “Because it’s what they are used to at home, once they see the strap then they will keep quiet.” |

| Use when other strategies don’t work (5) | “You know sometimes you do some of the strategies and the children don’t respond to it and you tend to want to get the strap.” |

| For antisocial behaviours (8) | “I don’t slap often but I do slap if a child is behaving bad, like spitting on a next child. Or if they do something bad to another child like slap them. I don’t normally do it—they have to do something bad and out the norm.” “I still beat but not often now. For stealing, that was the last thing I beat for.” |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baker-Henningham, H.; Scott, Y.; Bowers, M.; Francis, T. Evaluation of a Violence-Prevention Programme with Jamaican Primary School Teachers: A Cluster Randomised Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2797. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16152797

Baker-Henningham H, Scott Y, Bowers M, Francis T. Evaluation of a Violence-Prevention Programme with Jamaican Primary School Teachers: A Cluster Randomised Trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(15):2797. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16152797

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaker-Henningham, Helen, Yakeisha Scott, Marsha Bowers, and Taja Francis. 2019. "Evaluation of a Violence-Prevention Programme with Jamaican Primary School Teachers: A Cluster Randomised Trial" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 15: 2797. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16152797

APA StyleBaker-Henningham, H., Scott, Y., Bowers, M., & Francis, T. (2019). Evaluation of a Violence-Prevention Programme with Jamaican Primary School Teachers: A Cluster Randomised Trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(15), 2797. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16152797