Impact of a Web Program to Support the Mental Wellbeing of High School Students: A Quasi Experimental Feasibility Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.2.1. Eligibility

2.2.2. Settings and Locations

2.2.3. Recruitment

2.3. Web Program

2.3.1. Intervention Group

2.3.2. Active Control Group

2.3.3. Passive Control Group

2.4. Outcomes

2.4.1. Depression

2.4.2. Stress

2.4.3. Satisfaction

2.4.4. Acceptance

2.4.5. Usability Feedback

2.5. Sample Size

2.6. Randomization

2.7. Statistical Methods

2.8. Ethical Issues

3. Results

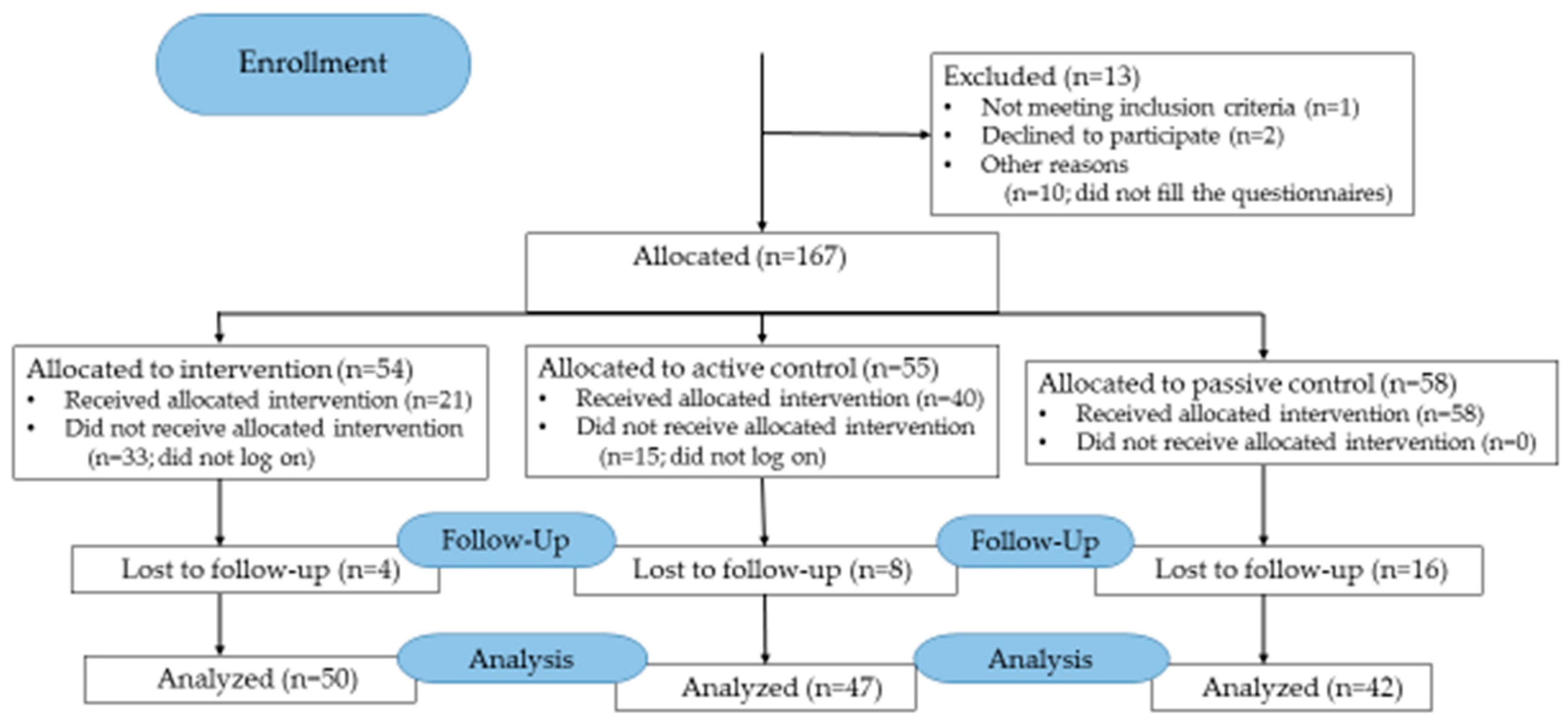

3.1. Participant Flow

3.2. Baseline Data

3.3. Numbers Analyzed

3.4. Outcomes

3.4.1. Depression

3.4.2. Stress

3.4.3. Satisfaction

3.4.4. Comparison between Program Users and Non-Users

3.4.5. Acceptance of the Program by Adolescents

3.4.6. Acceptance of the Program by Teachers

3.4.7. Usability Feedback

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ruangkanchanasetr, S.; Plitponkarnpim, A.; Hetrakul, P.; Kongsakon, R. Youth risk behavior survey: Bangkok, Thailand. J. Adolesc. Health 2005, 36, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horgan, A.; Sweeney, J. Young students’ use of the Internet for mental health information and support. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2010, 17, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leach, L.S.; Christensen, H.; Griffiths, K.M.; Jorm, A.F.; Mackinnon, A.J. Websites as a mode of delivering mental health information: Perceptions from the Australian public. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2007, 42, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, J.; Clarke, A. Internet information-seeking in mental health: Population survey. Br. J. Psychiatry 2006, 189, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umefjord, G.; Petersson, G.; Hamberg, K. Reasons for consulting a doctor on the Internet: Web survey of users of an Ask the Doctor service. J. Med. Internet Res. 2003, 5, e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lintvedt, O.K.; Griffiths, K.M.; Sørensen, K.; Østvik, A.R.; Wang, C.E.A.; Eisemann, M.; Waterloo, K. Evaluating the effectiveness and efficacy of unguided internet-based self-help intervention for the prevention of depression: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2013, 20, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, S.M.; Goodall, J.; Hetrick, S.E.; Parker, A.G.; Gilbertson, T.; Amminger, G.P.; Davey, C.G.; McGorry, P.D.; Gleeson, J.; Alvarez-Jimenez, M. Online and Social Networking Interventions for the Treatment of Depression in Young People: A Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, T.; Stallard, P.; Velleman, S. Computerised cognitive behavioural therapy for the prevention and treatment of depression and anxiety in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 13, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, S.; Campbell, A.J.; Ellis, L.A. The use of computerized self-help packages to treat adolescent depression and anxiety. J. Technol. Hum. Serv. 2010, 28, 144–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barak, A.; Hen, L.; Boniel-Nissim, M.; Shapira, N. A Comprehensive Review and a Meta-Analysis of the Effectiveness of Internet-Based Psychotherapeutic Interventions. J. Technol. Hum. Serv. 2008, 26, 109–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calear, A.L.; Christensen, H. Systematic review of school-based prevention and early intervention programs for depression. J. Adolesc. 2010, 33, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, C.A.; Lewis, L.K.; Ferrar, K.; Marshall, S.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Vandelanotte, C. Are health behavior change interventions that use online social networks effective? A systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnevale, T.D. Universal adolescent depression prevention programs: A review. J. Sch. Nurs. 2013, 29, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calear, A.L.; Batterham, P.J.; Poyser, C.T.; Mackinnon, A.J.; Griffiths, K.M.; Christensen, H. Cluster randomised controlled trial of the e-couch anxiety and worry program in schools. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 196, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, P.; Scott, R.; Eshkevari, E.; Jatta, F.; Leigh, E.; Harris, V.; Robinson, A.; Abeles, P.; Proudfoot, J.; Verduyn, C.; et al. Computerised CBT for depressed adolescents: Randomised controlled trial. Behav. Res. Ther. 2015, 73, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neil, A.L.; Batterham, P.; Christensen, H.; Bennett, K.; Griffiths, K.M. Predictors of adherence by adolescents to a cognitive behavior therapy website in school and community-based settings. J. Med. Internet Res. 2009, 11, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, J.; Corden, M.E.; Caccamo, L.; Tomasino, K.N.; Duffecy, J.; Begale, M.; Mohr, D.C. Design and evaluation of a peer network to support adherence to a web-based intervention for adolescents. Internet Interv. 2016, 6, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lillevoll, K.R.; Vangberg, H.C.B.; Griffiths, K.M.; Waterloo, K.; Eisemann, M.R. Uptake and adherence of a self-directed internet-based mental health intervention with tailored e-mail reminders in senior high schools in Norway. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manicavasagar, V.; Horswood, D.; Burckhardt, R.; Lum, A.; Hadzi-Pavlovic, D.; Parker, G. Feasibility and effectiveness of a web-based positive psychology program for youth mental health: Randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrieri, S.; Heider, D.; Conrad, I.; Blume, A.; König, H.; Riedel-Heller, S.G. School-based prevention programs for depression and anxiety in adolescence: A systematic review. Health Promot. Int. 2014, 29, 427–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Policy Coherence in the Application of Information and Communication Technologies for Development. 2009. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/ict/4d/44029390.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2019).

- WHO. Country Statistics and Global Health Estimates by WHO and UN Partners. 2015. Available online: http://www.who.int/gho/countries/tha.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 13 March 2019).

- WHO. WHO’s Work with Countries. WHO Country Cooperation Strategies and Briefs. 2014. Available online: http://www.who.int/countryfocus/cooperation_strategy/ccsbrief_tha_en.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2019).

- Patton, G.C.; Coffey, C.; Cappa, C.; Currie, D.; Riley, L.; Gore, F.; Degenhardt, L.; Richardson, D.; Astone, N.; Sangowawa, A.O.; et al. Health of the world’s adolescents: A synthesis of internationally comparable data. Lancet 2012, 379, 1665–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Areemit, R.; Suphakunpinyo, C.; Lumbiganon, P.; Sutra, S.; Thepsuthammarat, K. Thailand’s adolescent health situation: Prevention is the key. J. Med. Assoc. Thail. 2012, 95 (Suppl. 7), S51–S58. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Progress Report. Highlights 2012–2013, Department of Maternal, Newbors, Child and Adolescent Health (MCA). 2014. Available online: http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/MCA_progress-report-2012-13.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 13 March 2019).

- UNICEF. Review of Comprehensive Sexuality Education in Thailand. 2016. Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002475/247510E.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2019).

- Charoensuk, S. Negative thinking: A key factor in depressive symptoms in Thai adolescents. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2007, 28, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wacharasindhu, A.; Panyyayong, B. Psychiatric disorders in Thai school-aged children: I Prevalence. J. Med. Assoc. Thail. 2002, 85 (Suppl. 1), S125–S136. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global Health Observatory (GHO) Data. Psychiatrists and Nurses (per 100 000 Population). 2015. Available online: http://www.who.int/gho/mental_health/human_resources/psychiatrists_nurses/en/ (accessed on 13 March 2019).

- Slone, N.C.; Reese, R.J.; McClellan, M.J. Telepsychiatry outcome research with children and adolescents: A review of the literature. Psychol. Serv. 2012, 9, 271–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Ministry of Education. Towards a Learning Society in Thailand: Introduction to Education in Thailand; Bureau of International Cooperation: Bangkok, Thailand, 2008.

- World Education News & Reviews. Asia Pacific. Education in Thailand. 2018. Available online: https://wenr.wes.org/2018/02/education-in-thailand-2 (accessed on 13 March 2019).

- Välimäki, M.; Anttila, M.; Hätönen, H.; Koivunen, M.; Jakobsson, T.; Pitkänen, A.; Herrala, J.; Kuosmanen, L. Design and development process of patient-centered computer-based support system for patients with schizophrenia spectrum psychosis. Inform. Health Soc. Care 2008, 33, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Välimäki, M.; Kurki, M.; Hätönen, H.; Koivunen, M.; Selander, M.; Saarijärvi, S.; Anttila, M. Developing an Internet-based support system for adolescents with depression. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2012, 1, e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Välimäki, M.; Sittichai, R.; Anttila, M. Survey of adolescents’ stress in school life in Thailand: Implications for school health. J. Child. Health Care 2017, 21, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C. Conceptualization and measurement of coping during adolescence: A review of the literature. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2010, 42, 166–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.; Deci, E. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APA. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9 & PHQ-2). 2014. Available online: http://www.apa.org/pi/about/publications/caregivers/practice-settings/assessment/tools/patient-health.aspx (accessed on 13 March 2019).

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.; Williams, W. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. JGIM 2001, 16, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotrakul, M.; Sumrithe, S.; Saipanish, R. Reliability and validity of the Thai version of the PHQ-9. BMC Psychiatry 2008, 20, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.H. Review of the psychometric evidence of the perceived stress scale. Asian Nurs. Res. 2012, 6, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongpakaran, N.; Wongpakaran, T. The Thai version of the PSS-10: An Investigation of its psychometric properties. Biopsychosoc. Med. 2010, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attkisson, C.C.; Zwick, R. The client satisfaction questionnaire: Psychometric properties and correlations with service utilization and psychotherapy outcome. Eval. Program Plan. 1982, 5, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, D.L.; Attkisson, C.C.; Hargreaves, W.A.; Nguyen, T.D. Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: Development of a general scale. Eval. Program Plan. 1979, 2, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. User acceptance of computer technology: A comparisons of two theoretical models. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 982–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggelidis, V.P.; Chatzoglou, P.D. Using a modified technology acceptance model in hospitals. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2009, 78, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.E.; Han, S.S.; Yoo, K.H.; Yun, E.K. The impact of user’s perceived ability on online health information acceptance. Telemed. J. e-Health 2012, 18, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arain, M.; Campbell, M.J.; Cooper, C.L.; Lancaster, G.A. What is a pilot or feasibility study? A review of current practice and editorial policy. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2010, 10, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titov, N.; Dear, B.F.; McMillan, D.; Anderson, T.; Zou, J.; Sunderland, M. Psychometric comparison of the PHQ-9 and BDI-II for measuring response during treatment of depression. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2011, 40, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rickhi, B.; KaniaRichmond, A.; Moritz, S.; Cohen, J.; Paccagnan, P.; Dennis, C.; Liu, M.; Malhotra, S.; Steele, P.; Toews, J. Evaluation of a spirituality informed e-mental health tool as an intervention for major depressive disorder in adolescents and young adults—A randomized controlled pilot trial. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 15, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stallard, P.; Richardson, T.; Velleman, S.; Attwood, M. Computerized CBT (think, feel, do) for depression and anxiety in children and adolescents: Outcomes and feedback from a pilot randomized controlled trial. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2011, 39, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stasiak, K.; Hatcher, S.; Frampton, C.; Merry, S.N. A pilot double blind randomized placebo controlled trial of a prototype computer-based cognitive behavioural therapy program for adolescents with symptoms of depression. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2014, 42, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, B.; Tindall, L.; Littlewood, E.; Allgar, V.; Abeles, P.; Trepel, D.; Ali, S. Computerised cognitive-behavioural therapy for depression in adolescents: Feasibility results and 4-month outcomes of a UK randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e012834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keogh-Brown, M.; Bachmann, M.; Shepstone, L.; Hewitt, C.; Howe, A. Contamination in trials of educational interventions. Health Technol. Assess. 2007, 11, ix–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Välimäki, M.; Anttila, K.; Anttila, M.; Lahti, M. Web-Based Interventions Supporting Adolescents and Young People with Depressive Symptoms: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2017, 5, e180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Kearney, R.; Gibson, M.; Christensen, H.; Griffiths, K.M. Effects of a cognitive-behavioural internet program on depression, vulnerability to depression and stigma in adolescent males: A school-based controlled trial. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2006, 35, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridrici, M.; Lohaus, A. Stress-prevention in secondary schools: Online versus face-to-face training. Health Educ. 2009, 109, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Kearney, R.; Kang, K.; Christensen, H.; Griffiths, K. A controlled trial of a school-based internet program for reducing depressive symptoms in adolescent girls. Depress. Anxiety 2009, 26, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldbaum, S.; Craig, W.M.; Pepler, D.; Connolly, J. Developmental trajectories of victimization: Identifying risk and protective factors. In Bullying, Peer Harassment, and Victimization in the Schools: The Next Generation of Prevention; Elias, M.J., Zins, J.E., Eds.; The Haworth Press Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 139–156. [Google Scholar]

- Anttila, K.I.; Anttila, M.J.; Kurki, M.H.; Välimäki, M.A. Social relationships among adolescents as described in an electronic diary: A mixed methods study. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2017, 27, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, M.A.; Hardin, A.M.; Scott, C.L. Diffusion of virtual innovation. ACM SIGMIS Database 2007, 38, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, K.P. An overview of randomization techniques: An unbiased assessment of outcome in clinical research. J. Hum. Reprod. Sci. 2011, 4, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, E.H.; Austin, B.T.; Davis, C.; Hindmarsh, M.; Schaefer, J.; Bonomi, A. Improving chronic illness care: Translating evidence into action. Health Aff. 2001, 20, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jané-Llopis, E.; Andersson, P. Mental Health Promotion and Mental Disorder Prevention across European Member States: A Collection of Country Stories; European Communities: Luxembourg, 2006; Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/health/archive/ph_projects/2004/action1/docs/action1_2004_a02_30_en.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2019).

- Powers, J.D.; Bower, H.A.; Webber, K.C.; Martinson, N. Promoting School-Based Mental Health: Perspectives from School Practitioners. Soc. Work Ment. Health 2011, 9, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulliver, A.; Griffiths, K.M.; Christensen, H. Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2010, 10, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carral, V.; Braddick, F.; Jané-Llopis, E.; Jenkins, R. (Eds.) A Snapshot of Child and Adolescent Mental Health in Europe: Infrastructures, Policy and Programmes. In Child and Adolescent Mental Health in Europe: Infrastructures, Policy and Programmes; European Communities: Luxembourg, 2009; pp. 72–75. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzman, D.; Segal, R.; Drapeau, M. Perceptions of virtual reality among therapists who do not apply this technology in clinical practice. Psychol. Serv. 2012, 9, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, P.W.C.; Fu, K.W.; Chan, K.Y.K.; Chan, W.S.C.; Liu, P.M.Y.; Law, Y.W.; Yip, P.S.F. Effectiveness of a universal school-based programme for preventing depression in Chinese adolescents: A quasi-experimental pilot study. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 142, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naslund, J.A.; Aschbrenner, K.A.; Araya, R.; Marsch, L.A.; Unützer, J.; Patel, V.; Bartels, S.J. Digital technology for treating and preventing mental disorders in low-income and middle-income countries: A narrative review of the literature. Lancet Psychiatry 2017, 4, 486–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Intervention n = 54 | Active Control n = 55 | Passive Control n = 58 | p-Value | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | Mean | SD | n | % | Mean | SD | n | % | Mean | SD | ||

| Age | 15.76 | 0.70 | 15.78 | 0.88 | 16.22 | 0.56 | 0.001 | ||||||

| Female gender | 34 | 64.2 | 30 | 54.5 | 50 | 86.2 | 0.001 | ||||||

| Regular school attendance | 53 | 100.0 | 54 | 98.2 | 56 | 96.6 | 0.395 | ||||||

| Previous mental health service use | 2 | 3.8 | 1 | 1.9 | 2 | 3.4 | 0.823 | ||||||

| Depression score (PHQ-9) | 8.07 | 4.61 | 7.62 | 3.05 | 7.79 | 4.08 | 0.833 | ||||||

| Stress score (T-PSS-10) | 15.87 | 4.91 | 15.45 | 4.37 | 16.55 | 5.47 | 0.493 | ||||||

| Satisfaction score (CSQ-8) | 29 | 53.7 | 18.72 | 6.09 | 17 | 30.9 | 17.53 | 7.76 | 32 | 55.2 | 23.81 | 2.60 | 0.001 |

| Characteristics | Baseline | |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention % | Active Control % | |

| Age | n = 6 | n = 4 |

| Under 30 | 50 | 75 |

| 30–39 years | 0 | 25 |

| 40–49 years | 17 | 0 |

| Over 50 | 33 | 0 |

| Gender | n = 6 | n = 4 |

| Male | 0 | 25 |

| Female | 100 | 75 |

| Teacher working experience | n = 3 | n = 3 |

| Under 10 years | 0 | 100 |

| 10–19 years | 0 | 0 |

| 20–29 years | 33 | 0 |

| over 30 years | 67 | 0 |

| Does the school have methods to support adolescent wellbeing and prevent mental health problems | n = 5 | n = 4 |

| Yes | 0 | 75 |

| No | 100 | 25 |

| Are teachers satisfied with methods | n = 3 | n = 4 |

| Yes | 67 | 75 |

| No | 33 | 25 |

| Does the teacher have useful experiences of methods | n = 3 | n = 4 |

| Yes | 0 | 75 |

| No | 100 | 25 |

| Are methods easy to use | n = 3 | n = 4 |

| Yes | 67 | 75 |

| No | 33 | 25 |

| Are methods harmful | n = 3 | n = 4 |

| Yes | 0 | 50 |

| No | 100 | 50 |

| Does the teacher have intentions to use the methods in the future | n = 3 | n = 4 |

| Yes | 67 | 100 |

| No | 33 | 0 |

| Intervention (54/50) | Active Control (55/47) | Passive Control (58/42) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | BL Mean (SD) | FU Mean (SD) | Change Mean | BL Mean (SD) | FU Mean (SD) | Change Mean | BL Mean (SD) | FU Mean (SD) | Change Mean | p-Value |

| PHQ-9 depression | n = 54 7.8 (4.5) | n = 47 7.5 (3.7) | 0.3 | n = 55 7.8 (3.0) | n = 46 6.9 (3.5) | 0.9 | n = 58 7.8 (3.7) | n = 42 7.0 (3.1) | 0.8 | 0.594 |

| T-PSS-10 stress | n = 55 15.6 (4.9) | n = 50 16.3 (5.1) | −0.7 | n = 55 15.9 (4.3) | n = 47 15.5 (4.8) | 0.4 | n = 58 16.1 (4.9) | n = 42 15.2 (5.0) | 0.9 | 0.178 |

| CSQ-8 satisfaction | n = 29 19.7 (5.6) | n = 26 19.8 (3.4) | −0.1 | n = 17 18.8 (7.4) | n = 15 19.4 (3.5) | −0.6 | n = 32 23.4 (2.5) | n = 16 19.6 (5.2) | 3.8 | 0.101 |

| Statement | Intervention n (%) * | Active control n (%) * | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | n | n | p | |||

| Have you been satisfied with the program? | 96 | 34 (69) | 49 | 40 (85) | 47 | 0.067 |

| Have you experienced the program to be useful? | 96 | 16 (33) | 49 | 10 (21) | 47 | 0.210 |

| Is the program easy to use? | 96 | 30 (61) | 49 | 34 (72) | 47 | 0.248 |

| Has the program caused any harm to you? | 96 | 1 (2) | 49 | 3 (6) | 47 | 0.287 |

| Would you use this kind of program in the future? | 95 | 27 (56) | 48 | 27 (57) | 47 | 0.906 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anttila, M.; Sittichai, R.; Katajisto, J.; Välimäki, M. Impact of a Web Program to Support the Mental Wellbeing of High School Students: A Quasi Experimental Feasibility Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2473. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16142473

Anttila M, Sittichai R, Katajisto J, Välimäki M. Impact of a Web Program to Support the Mental Wellbeing of High School Students: A Quasi Experimental Feasibility Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(14):2473. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16142473

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnttila, Minna, Ruthaychonnee Sittichai, Jouko Katajisto, and Maritta Välimäki. 2019. "Impact of a Web Program to Support the Mental Wellbeing of High School Students: A Quasi Experimental Feasibility Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 14: 2473. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16142473

APA StyleAnttila, M., Sittichai, R., Katajisto, J., & Välimäki, M. (2019). Impact of a Web Program to Support the Mental Wellbeing of High School Students: A Quasi Experimental Feasibility Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(14), 2473. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16142473